Mở bài

Khoảng cách số (digital divide) – sự chênh lệch về khả năng tiếp cận và sử dụng công nghệ thông tin giữa các nhóm người – đang trở thành một trong những chủ đề xã hội quan trọng và thường xuyên xuất hiện trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Theo thống kê từ Cambridge IELTS và British Council, các bài đọc về công nghệ, giáo dục và bất bình đẳng xã hội chiếm khoảng 25-30% tổng số đề thi thực tế.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages từ dễ đến khó, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng theo đúng format thi thật. Bạn sẽ được luyện tập với các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến như True/False/Not Given, Matching Headings, Multiple Choice và Summary Completion. Mỗi câu hỏi đều có đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin, cách paraphrase và chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với cấu trúc đề thi, rèn luyện kỹ năng đọc hiểu học thuật và nâng cao vốn từ vựng chuyên ngành công nghệ – xã hội.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút cho 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Độ khó tăng dần từ Passage 1 đến Passage 3, yêu cầu thí sinh có khả năng quản lý thời gian hiệu quả.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (13 câu hỏi, độ khó Easy)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (13 câu hỏi, độ khó Medium)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (14 câu hỏi, độ khó Hard)

Lưu ý dành 2-3 phút cuối để chuyển đáp án vào answer sheet và kiểm tra lại.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Chọn đáp án đúng từ các phương án cho sẵn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hoặc không được đề cập

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn tương ứng

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu với từ trong bài đọc

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào tóm tắt nội dung

- Matching Headings – Chọn tiêu đề phù hợp cho từng đoạn

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Bridging the Gap: Technology’s Promise for Digital Inclusion

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The digital divide refers to the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard to both their opportunities to access information and communication technologies (ICTs) and their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities. This divide exists not only between developed and developing countries but also within nations themselves, affecting rural communities, elderly populations, and low-income households disproportionately.

In recent years, technology has emerged as both a cause of and a potential solution to this divide. While the rapid advancement of digital technologies has created new forms of inequality, it has also opened up unprecedented opportunities for bridging these gaps. Smartphones, for instance, have become more affordable and accessible, allowing millions of people in developing countries to connect to the Internet for the first time. According to recent statistics, mobile phone penetration in Africa reached 80% in 2022, compared to just 25% a decade earlier.

Educational technology represents one of the most promising areas for addressing digital inequality. Online learning platforms, digital textbooks, and educational apps have made quality education more accessible to students in remote areas. During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools worldwide were forced to adopt remote learning solutions, which highlighted both the potential and the challenges of digital education. While students in well-connected urban areas could continue their studies relatively smoothly, those in rural regions or from disadvantaged backgrounds often struggled due to lack of devices or reliable internet connections.

Governments and non-profit organizations have launched various initiatives to reduce the digital divide. One successful example is India’s Digital India campaign, which aims to transform the country into a digitally empowered society. The program focuses on providing digital infrastructure as a utility to every citizen, governance and services on demand, and digital empowerment of citizens. Similar programs have been implemented in countries like Rwanda, where the government has partnered with private companies to extend internet coverage to rural areas.

Community technology centers have also played a crucial role in providing access to computers and the Internet for underserved populations. These centers offer not just equipment but also training programs to help people develop digital literacy skills. In the United States, public libraries have transformed into community hubs offering free Internet access, computer training, and assistance with online job applications and government services. This approach recognizes that simply providing technology is insufficient; people also need the skills and knowledge to use it effectively.

Affordable internet access remains a critical challenge in many parts of the world. While technology costs have decreased significantly, internet services remain expensive relative to income in many developing countries. According to the Alliance for Affordable Internet, internet access is considered affordable when 1GB of mobile data costs less than 2% of average monthly income. However, in many African countries, this figure exceeds 5%, making regular internet use prohibitively expensive for many citizens.

The private sector has also recognized the business opportunity in expanding digital access. Companies like Google and Facebook have invested in projects to extend internet connectivity to underserved areas. Google’s Project Loon used high-altitude balloons to provide Internet access to remote regions, while Facebook’s Free Basics program offers free access to basic internet services in developing countries. However, these initiatives have faced criticism regarding net neutrality and concerns that they create a “two-tier internet” system.

Looking forward, emerging technologies such as 5G networks, satellite internet, and low-cost devices promise to further reduce the digital divide. Companies like SpaceX and Amazon are developing satellite constellations that could provide high-speed internet access to even the most remote locations. Meanwhile, manufacturers are producing increasingly affordable smartphones and tablets specifically designed for developing markets, with features like extended battery life and offline functionality.

However, technology alone cannot solve the digital divide. Addressing this challenge requires a comprehensive approach that includes investment in infrastructure, education and training programs, affordable pricing policies, and content that is relevant and accessible to diverse populations. Moreover, attention must be paid to ensuring that technological solutions are sustainable and appropriate for local contexts, rather than simply transplanting models from developed countries.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

1. According to the passage, the digital divide exists:

A. Only between developed and developing countries

B. Only within individual nations

C. Both between and within countries

D. Primarily in urban areas

2. What does the passage say about smartphones in developing countries?

A. They are still too expensive for most people

B. They have helped millions connect to the Internet

C. They are less popular than desktop computers

D. They are mainly used for phone calls

3. During the COVID-19 pandemic, students in rural areas:

A. Had no problems with online learning

B. Performed better than urban students

C. Often faced difficulties due to connectivity issues

D. Refused to participate in remote learning

4. India’s Digital India campaign focuses on:

A. Only providing internet infrastructure

B. Exclusively targeting urban populations

C. Digital infrastructure, governance, and citizen empowerment

D. Competing with private technology companies

5. According to the Alliance for Affordable Internet, internet is affordable when 1GB costs:

A. Less than 1% of monthly income

B. Less than 2% of monthly income

C. Less than 5% of monthly income

D. Less than 10% of monthly income

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Write TRUE if the statement agrees with the information, FALSE if the statement contradicts the information, or NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this.

6. Mobile phone penetration in Africa has more than tripled in the past ten years.

7. All students worldwide adapted successfully to online learning during the pandemic.

8. Public libraries in the United States charge fees for computer training programs.

9. Project Loon was more successful than Facebook’s Free Basics program.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

10. Community technology centers provide both equipment and programs to develop __ in users.

11. Critics of some private sector initiatives are concerned about creating a __ internet system.

12. New affordable devices for developing markets include features like offline functionality and __.

13. Solving the digital divide requires a __ that goes beyond just providing technology.

PASSAGE 2 – The Paradox of Technological Solutions to Digital Inequality

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The relationship between technology and the digital divide presents a fascinating paradox: the very innovations designed to democratize access to information and opportunities can simultaneously exacerbate existing inequalities. This dual nature of technological advancement requires careful examination, particularly as policymakers and technology companies increasingly position digital solutions as panaceas for social and economic disparities.

A. Historical analysis reveals that each wave of technological innovation has initially widened gaps before gradually enabling broader access. The introduction of personal computers in the 1980s created a stark divide between those who could afford these devices and those who could not. Similarly, early Internet access was largely confined to affluent communities and academic institutions. However, as technologies matured and economies of scale reduced costs, accessibility improved dramatically. This pattern suggests that short-term inequality may be an inevitable byproduct of innovation, raising important questions about whether intervention strategies should focus on accelerating the diffusion process or preventing initial disparities.

B. Contemporary efforts to address digital exclusion must grapple with the multidimensional nature of the divide. Researchers now distinguish between first-level and second-level digital divides. The first-level divide concerns physical access to technology and connectivity, while the second-level divide relates to the skills, knowledge, and social capital necessary to benefit from digital resources. Increasingly, scholars also identify a third-level divide concerning the tangible outcomes and benefits individuals derive from technology use. A person may have a smartphone and basic digital literacy but still lack the advanced competencies required for online entrepreneurship or accessing complex digital services.

C. The proliferation of mobile technology has been heralded as a breakthrough in addressing first-level digital divides, particularly in developing regions. Mobile money services like M-Pesa in Kenya have revolutionized financial inclusion, enabling millions of previously unbanked individuals to participate in the formal economy. Telemedicine applications are bringing healthcare consultations to remote villages, while agricultural apps provide farmers with real-time market prices and weather forecasts. These developments demonstrate technology’s capacity to leapfrog traditional infrastructure limitations.

D. Nevertheless, the mobile-first approach to digital inclusion harbors significant limitations. The small screen size and limited processing power of budget smartphones constrain the complexity of tasks users can perform. Creating content, conducting detailed research, or using sophisticated software remains challenging on mobile devices. This functionality gap means that mobile-only users may remain perpetual consumers of content rather than creators, reinforcing existing power dynamics in the digital sphere. Furthermore, data costs continue to present substantial barriers in many regions, with users forced to make difficult choices between essential expenses and internet connectivity.

E. The educational dimension of the digital divide has acquired heightened urgency in the post-pandemic era. The abrupt transition to remote learning exposed profound inequalities in students’ home learning environments. While advantaged students had access to personal devices, high-speed internet, and parental support, disadvantaged peers often shared a single device among siblings, relied on intermittent mobile connections, and lacked adult guidance for navigating online platforms. Research indicates that these disparities contributed to learning loss disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations, potentially widening achievement gaps for years to come.

F. Addressing educational digital divides requires more than distributing devices. Studies examining one-to-one computer programs, where each student receives a personal device, show mixed results. Some implementations have enhanced student engagement and personalized learning, while others have yielded minimal academic improvements and even distraction. The critical variables appear to be teacher training, curriculum integration, and ongoing technical support. Technology proves most effective when embedded within pedagogical frameworks that emphasize critical thinking and collaboration rather than serving as mere content delivery mechanisms.

G. The role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in either bridging or widening digital divides remains contested. Optimists argue that AI-powered tools can provide personalized tutoring, language translation, and accessibility features that democratize access to information and services. Adaptive learning platforms adjust content difficulty based on individual progress, potentially helping struggling students catch up. Voice interfaces enable illiterate or low-literacy users to access digital services previously requiring reading skills. However, concerns abound regarding algorithmic bias, privacy violations, and the concentration of AI capabilities within wealthy corporations and nations.

H. Critics warn that AI systems trained predominantly on data from developed countries may perpetuate cultural biases and prove less effective for marginalized populations. Facial recognition systems have demonstrated higher error rates for darker skin tones, while natural language processing algorithms perform better in English than in many other languages. Moreover, the computational resources required for cutting-edge AI development remain concentrated in a handful of technology companies and research institutions, raising questions about who shapes and benefits from these powerful technologies.

A sustainable approach to technology-enabled digital inclusion must prioritize local ownership, cultural relevance, and community participation. Top-down interventions that ignore local contexts and needs have repeatedly failed, whereas co-design processes involving community members tend to produce more appropriate and lasting solutions. For instance, low-tech solutions like community radio combined with mobile phones have proven highly effective for agricultural extension in several African countries, demonstrating that the newest technology is not always the most suitable.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Matching Headings

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs B-F from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. The limitations of mobile technology in bridging the gap

ii. Historical patterns of technology adoption and inequality

iii. The transformation of financial services through mobile phones

iv. Understanding different levels of digital divides

v. Educational challenges exposed by the pandemic

vi. The importance of teacher preparation in technology integration

vii. Mobile applications revolutionizing agriculture

viii. The debate surrounding artificial intelligence

14. Paragraph B

15. Paragraph C

16. Paragraph D

17. Paragraph E

18. Paragraph F

Questions 19-22: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

19. Early technological innovations inevitably create temporary inequality before access becomes widespread.

20. Mobile phones are sufficient for addressing all aspects of the digital divide.

21. One-to-one computer programs in schools always lead to improved academic performance.

22. AI systems perform equally well across all languages and cultural contexts.

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Addressing the digital divide requires understanding its complexity. Beyond physical access (first-level divide), people need appropriate skills and (23) __ to use technology effectively. Mobile technology has enabled (24) __ in developing countries through services like M-Pesa. However, mobile devices have a (25) __ that limits users to consuming rather than creating content. Successful interventions require (26) __, cultural appropriateness, and involvement of community members in the design process.

PASSAGE 3 – Reconceptualizing Digital Equity in an Age of Ubiquitous Computing

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The discourse surrounding the digital divide has undergone considerable epistemological evolution since its emergence in the late 1990s. Initially conceived as a binary distinction between the connected and unconnected, contemporary scholarship recognizes digital inequality as a multifaceted phenomenon encompassing access, usage patterns, skill levels, and the socio-economic returns derived from technology engagement. This reconceptualization reflects not merely academic refinement but fundamental shifts in the technological landscape itself, as ubiquitous computing, artificial intelligence, and datafication reshape the nature and implications of digital participation.

The theoretical frameworks employed to analyze digital divides have diversified considerably, moving beyond simple diffusion models toward more nuanced approaches drawing from sociology, political economy, and critical theory. Van Dijk’s resources and appropriation theory posits that digital inequality stems from unequal distribution of four types of resources: temporal, material, mental, and social. This framework illuminates why merely providing technological access proves insufficient; individuals require time to use technology, financial resources to sustain connectivity, cognitive capabilities to navigate digital environments, and social networks that support and encourage technology adoption. The theory thus explains the persistence of digital divides even as hardware costs decline and infrastructure expands.

Intersectionality theory offers additional analytical purchase by examining how multiple dimensions of inequality—including race, class, gender, age, disability, and geographic location—interact to shape digital experiences. Research demonstrates that disadvantage compounds across these categories; elderly, low-income women in rural areas face markedly different barriers than young urban professionals. Moreover, these intersecting inequalities manifest differently across national contexts, reflecting varying regulatory environments, cultural norms, and historical trajectories. The digital divide thus cannot be understood as a singular, universal phenomenon but must be analyzed with attention to contextual specificity.

The political economy of digital platforms has emerged as a crucial consideration in contemporary analyses of digital inequality. The dominance of a small number of technology corporations over digital infrastructure, platforms, and data raises fundamental questions about power asymmetries in the digital sphere. These companies shape not only what technologies are available and at what cost but also the architectures of digital spaces—determining what actions are possible, what information is visible, and whose voices are amplified. The business models predicated on data extraction and surveillance capitalism create new forms of exploitation, where users provide valuable data and attention labor in exchange for ostensibly “free” services.

This extractive model disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, who may be most reliant on free digital services yet least equipped to understand privacy implications or protect their data. Furthermore, the algorithmic curation of information creates filter bubbles and echo chambers that may reinforce existing biases and limit exposure to diverse perspectives. The opacity of algorithmic decision-making systems—often protected as proprietary information—prevents meaningful accountability when these systems produce discriminatory outcomes in consequential domains like employment, credit, housing, and criminal justice.

The COVID-19 pandemic functioned as a global natural experiment, simultaneously accelerating digital transformation and exposing the costs of digital exclusion with unprecedented clarity. Remote work arrangements, telehealth services, online education, and e-commerce transitioned from conveniences to necessities virtually overnight. Those lacking adequate connectivity or digital skills found themselves unable to access employment, healthcare, education, and essential services. The pandemic thus transformed the digital divide from a source of relative disadvantage into a matter of fundamental rights—raising questions about whether internet access should be recognized as essential infrastructure analogous to electricity or water.

Policy responses to digital inequality have varied considerably across national contexts, reflecting differing ideological orientations and institutional capacities. Some nations have adopted universal service approaches, treating internet access as a public utility subject to government provision or heavy regulation. South Korea’s high-speed internet infrastructure, built through substantial public investment and public-private partnerships, exemplifies this model. Conversely, the United States has largely relied on market mechanisms supplemented by targeted subsidies for low-income households and rural areas, with more uneven results.

Emerging regulatory frameworks like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) attempt to address power imbalances between individuals and platforms by establishing data rights and consent requirements. However, implementation challenges abound, and critics argue that compliance costs may actually favor large incumbent firms capable of absorbing regulatory expenses while smaller competitors struggle. Moreover, the effectiveness of rights-based approaches depends on individuals possessing sufficient digital literacy to understand and exercise their rights—again highlighting how regulatory solutions must be coupled with educational initiatives.

The frontier of digital divide research increasingly examines not simply whether people use technology but how they use it and with what consequences. Capital-enhancing uses of technology—such as skill development, entrepreneurship, civic participation, and accessing high-quality information—differ fundamentally from recreational or passive consumption activities in their potential to improve socio-economic circumstances. Research reveals systematic differences in usage patterns across demographic groups, with disadvantaged populations more likely to use technology for entertainment while advantaged groups deploy it for capital accumulation.

This usage divide reflects and reinforces broader inequalities, creating feedback loops where initial disadvantage leads to less beneficial technology use, which perpetuates disadvantage. Breaking these cycles requires holistic interventions addressing not only access and skills but also the social conditions that shape technology engagement—including education quality, employment opportunities, and community resources. Moreover, attention must be paid to developing technologies and digital content that are genuinely responsive to the needs and cultural contexts of diverse populations, rather than assuming that tools designed for affluent, educated users will serve everyone equally.

Looking forward, emerging technologies including artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, blockchain, and quantum computing will likely create new iterations of digital divides. Each wave of innovation generates first-mover advantages for those positioned to adopt and exploit new capabilities while potentially rendering previous skills and technologies obsolete. Ensuring digital equity in this rapidly evolving landscape requires sustained institutional commitment, adequate resources, and inclusive design processes that center the needs of marginalized populations. Only through such comprehensive efforts can the democratizing potential of technology be realized rather than remaining a perpetually deferred promise.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

27. According to the passage, the concept of the digital divide has evolved from:

A. A complex phenomenon to a simple binary

B. A binary distinction to a multifaceted phenomenon

C. A technological issue to a social issue

D. A temporary problem to a permanent condition

28. Van Dijk’s resources and appropriation theory identifies how many types of resources?

A. Two

B. Three

C. Four

D. Five

29. According to the passage, intersectionality theory is useful because it:

A. Simplifies the analysis of digital inequality

B. Focuses exclusively on economic factors

C. Examines how multiple dimensions of inequality interact

D. Applies only to developed countries

30. The passage suggests that algorithmic curation:

A. Always promotes diverse perspectives

B. Is completely transparent to users

C. May reinforce existing biases

D. Has no impact on information access

31. The COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on digital inequality was to:

A. Completely solve the digital divide

B. Have no significant impact

C. Transform it from relative disadvantage to a matter of fundamental rights

D. Only affect developing countries

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each statement (32-36) with the correct theoretical framework or concept (A-F).

A. Resources and appropriation theory

B. Intersectionality theory

C. Political economy perspective

D. Surveillance capitalism

E. Universal service approach

F. Usage divide

32. Digital inequality results from unequal distribution of temporal, material, mental, and social resources.

33. Multiple dimensions of inequality compound across categories like race, class, and gender.

34. Users provide valuable data in exchange for free services, creating new forms of exploitation.

35. Internet access should be treated as a public utility requiring government provision.

36. Differences exist between capital-enhancing and recreational uses of technology.

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What does the passage say protects algorithmic decision-making systems from accountability?

38. Which regulation attempts to establish data rights and consent requirements in Europe?

39. What type of advantages do early adopters of new technologies gain?

40. What kind of design processes does the passage recommend to ensure digital equity?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- C

- B

- C

- C

- B

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT GIVEN

- NOT GIVEN

- digital literacy skills

- two-tier

- extended battery life

- comprehensive approach

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- iv

- iii (Note: Heading for C about mobile technology revolution)

- i

- v

- vi

- YES

- NO

- NO

- NO

- social capital

- financial inclusion

- functionality gap

- local ownership

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- C

- C

- C

- A

- B

- D

- E

- F

- proprietary information

- GDPR / General Data Protection Regulation

- first-mover advantages

- inclusive design processes

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: digital divide, exists

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-4

- Giải thích: Câu đầu tiên nói rõ “This divide exists not only between developed and developing countries but also within nations themselves” – khoảng cách số tồn tại cả giữa các quốc gia VÀ trong nội bộ từng quốc gia. Đáp án A và B chỉ đề cập một khía cạnh, D không được nhắc đến.

Câu 2: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: smartphones, developing countries

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Smartphones…have become more affordable and accessible, allowing millions of people in developing countries to connect to the Internet for the first time” – điện thoại thông minh đã giúp hàng triệu người kết nối Internet. Paraphrase: “allowing millions to connect” = “helped millions connect to the Internet”.

Câu 3: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: COVID-19 pandemic, students, rural areas

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-8

- Giải thích: “While students in well-connected urban areas could continue their studies relatively smoothly, those in rural regions…often struggled due to lack of devices or reliable internet connections” – học sinh vùng nông thôn gặp khó khăn vì thiếu thiết bị và kết nối. Đây là paraphrase của đáp án C.

Học sinh vùng nông thôn gặp khó khăn trong học trực tuyến do thiếu thiết bị và kết nối internet

Học sinh vùng nông thôn gặp khó khăn trong học trực tuyến do thiếu thiết bị và kết nối internet

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Mobile phone penetration, Africa, tripled, ten years

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: “Mobile phone penetration in Africa reached 80% in 2022, compared to just 25% a decade earlier” – từ 25% lên 80% trong 10 năm, tăng hơn gấp ba lần (3.2 lần chính xác). Câu phát biểu đúng.

Câu 7: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all students, adapted successfully, pandemic

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-8

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ học sinh vùng thành thị học tốt nhưng học sinh nông thôn và khó khăn “struggled” – gặp khó khăn. Từ “all students…successfully” mâu thuẫn với thông tin này nên là FALSE.

Câu 10: digital literacy skills

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: Community technology centers, provide, equipment, programs

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “These centers offer not just equipment but also training programs to help people develop digital literacy skills” – các trung tâm cung cấp thiết bị và chương trình đào tạo để phát triển kỹ năng số.

Câu 13: comprehensive approach

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: solving digital divide, requires, beyond technology

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Addressing this challenge requires a comprehensive approach that includes investment in infrastructure, education…” – giải quyết thách thức này cần một cách tiếp cận toàn diện.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: iv (Understanding different levels of digital divides)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph B

- Giải thích: Đoạn B giải thích chi tiết về “first-level”, “second-level” và “third-level digital divides” – ba cấp độ khác nhau của khoảng cách số. Tiêu đề iv phù hợp nhất vì tập trung vào việc hiểu các cấp độ khác nhau này.

Câu 15: iii (The transformation of financial services)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph C

- Giải thích: Đoạn C tập trung vào “Mobile money services like M-Pesa in Kenya have revolutionized financial inclusion” – dịch vụ tiền di động đã cách mạng hóa tài chính toàn diện. Đây chính là sự chuyển đổi dịch vụ tài chính qua điện thoại di động.

Câu 16: i (The limitations of mobile technology)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph D

- Giải thích: Đoạn D bắt đầu bằng “Nevertheless, the mobile-first approach…harbors significant limitations” và liệt kê các hạn chế như màn hình nhỏ, công suất xử lý hạn chế, chi phí dữ liệu cao. Tiêu đề này khớp hoàn toàn.

Câu 19: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph A, dòng 2-6

- Giải thích: “Each wave of technological innovation has initially widened gaps before gradually enabling broader access…This pattern suggests that short-term inequality may be an inevitable byproduct of innovation” – tác giả đồng ý rằng bất bình đẳng tạm thời là không thể tránh khỏi.

Câu 20: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph D

- Giải thích: Đoạn D nói rõ “the mobile-first approach…harbors significant limitations” và “mobile-only users may remain perpetual consumers…rather than creators” – điện thoại di động KHÔNG đủ để giải quyết mọi khía cạnh. Quan điểm tác giả trái ngược với phát biểu.

Sơ đồ minh họa ba cấp độ của khoảng cách số trong xã hội hiện đại

Sơ đồ minh họa ba cấp độ của khoảng cách số trong xã hội hiện đại

Câu 23: social capital

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph B, dòng 5-8

- Giải thích: “The second-level divide relates to the skills, knowledge, and social capital necessary to benefit from digital resources” – cấp độ thứ hai liên quan đến kỹ năng, kiến thức và vốn xã hội.

Câu 25: functionality gap

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph D, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “This functionality gap means that mobile-only users may remain perpetual consumers of content rather than creators” – khoảng cách chức năng khiến người dùng chỉ có điện thoại trở thành người tiêu thụ hơn là sáng tạo nội dung.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: concept, digital divide, evolved

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Initially conceived as a binary distinction between the connected and unconnected, contemporary scholarship recognizes digital inequality as a multifaceted phenomenon” – ban đầu là phân biệt nhị phân, nay được nhận thực là hiện tượng đa diện. Paraphrase chính xác của đáp án B.

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Van Dijk’s theory, resources

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “Van Dijk’s resources and appropriation theory posits that digital inequality stems from unequal distribution of four types of resources: temporal, material, mental, and social” – lý thuyết xác định BỐN loại tài nguyên.

Câu 31: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: COVID-19 pandemic, effect, digital inequality

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “The pandemic thus transformed the digital divide from a source of relative disadvantage into a matter of fundamental rights” – đại dịch chuyển khoảng cách số từ bất lợi tương đối thành vấn đề quyền cơ bản.

Câu 32: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Giải thích: Phát biểu về bốn loại tài nguyên (temporal, material, mental, social) khớp chính xác với Resources and appropriation theory của Van Dijk được mô tả trong đoạn 2.

Câu 33: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Giải thích: “Multiple dimensions of inequality—including race, class, gender, age, disability, and geographic location—interact” là định nghĩa chính xác của Intersectionality theory trong đoạn 3.

Câu 37: proprietary information

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: “The opacity of algorithmic decision-making systems—often protected as proprietary information—prevents meaningful accountability” – tính mờ đục của hệ thống thuật toán thường được bảo vệ như thông tin độc quyền, ngăn cản trách nhiệm giải trình.

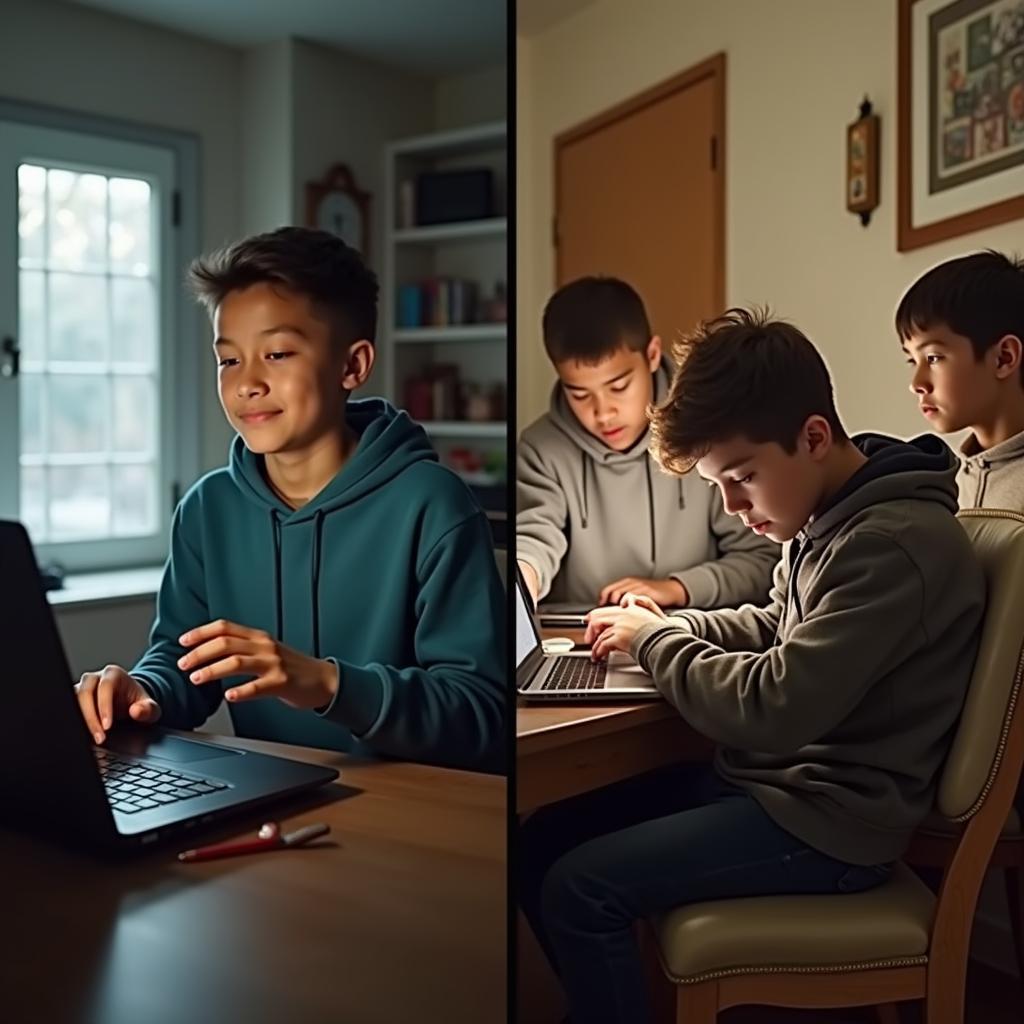

Tác động của đại dịch COVID-19 lên bất bình đẳng giáo dục số

Tác động của đại dịch COVID-19 lên bất bình đẳng giáo dục số

Câu 39: first-mover advantages

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Each wave of innovation generates first-mover advantages for those positioned to adopt and exploit new capabilities” – mỗi làn sóng đổi mới tạo ra lợi thế người đi trước cho những người sẵn sàng áp dụng công nghệ mới.

Câu 40: inclusive design processes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “Ensuring digital equity…requires sustained institutional commitment, adequate resources, and inclusive design processes that center the needs of marginalized populations” – đảm bảo công bằng số đòi hỏi các quy trình thiết kế toàn diện.

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| digital divide | n | /ˈdɪdʒɪtl dɪˈvaɪd/ | Khoảng cách số | The digital divide refers to the gap between individuals… | bridge the digital divide, address the digital divide |

| socio-economic | adj | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk/ | Thuộc về kinh tế xã hội | individuals at different socio-economic levels | socio-economic status, socio-economic factors |

| penetration | n | /ˌpenɪˈtreɪʃn/ | Sự thâm nhập, tỷ lệ phủ sóng | Mobile phone penetration in Africa reached 80% | market penetration, internet penetration |

| remote learning | n | /rɪˈməʊt ˈlɜːnɪŋ/ | Học từ xa | schools adopted remote learning solutions | remote learning platform, remote learning environment |

| digital literacy | n | /ˈdɪdʒɪtl ˈlɪtərəsi/ | Kiến thức số, khả năng sử dụng công nghệ | help people develop digital literacy skills | improve digital literacy, digital literacy training |

| infrastructure | n | /ˈɪnfrəstrʌktʃə(r)/ | Cơ sở hạ tầng | providing digital infrastructure as a utility | build infrastructure, digital infrastructure |

| affordable | adj | /əˈfɔːdəbl/ | Có khả năng chi trả, giá phải chăng | Affordable internet access remains a challenge | affordable housing, affordable prices |

| net neutrality | n | /net njuːˈtræləti/ | Tính trung lập của mạng | concerns regarding net neutrality | protect net neutrality, net neutrality regulations |

| underserved | adj | /ˌʌndəˈsɜːvd/ | Không được phục vụ đầy đủ | providing access for underserved populations | underserved communities, underserved areas |

| sustainability | n | /səˌsteɪnəˈbɪləti/ | Tính bền vững | ensuring that solutions are sustainable | environmental sustainability, long-term sustainability |

| comprehensive | adj | /ˌkɒmprɪˈhensɪv/ | Toàn diện, đầy đủ | requires a comprehensive approach | comprehensive plan, comprehensive solution |

| empowerment | n | /ɪmˈpaʊəmənt/ | Sự trao quyền, tăng cường năng lực | digital empowerment of citizens | women empowerment, community empowerment |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| innovation | n | /ˌɪnəˈveɪʃn/ | Sự đổi mới, sáng tạo | innovations designed to democratize access | technological innovation, drive innovation |

| exacerbate | v | /ɪɡˈzæsəbeɪt/ | Làm trầm trọng thêm | can simultaneously exacerbate existing inequalities | exacerbate the problem, exacerbate tensions |

| paradox | n | /ˈpærədɒks/ | Nghịch lý | The relationship presents a fascinating paradox | apparent paradox, paradox of choice |

| multidimensional | adj | /ˌmʌltiˌdaɪˈmenʃənl/ | Đa chiều | the multidimensional nature of the divide | multidimensional approach, multidimensional problem |

| proliferation | n | /prəˌlɪfəˈreɪʃn/ | Sự gia tăng nhanh chóng | The proliferation of mobile technology | nuclear proliferation, rapid proliferation |

| breakthrough | n | /ˈbreɪkθruː/ | Đột phá | heralded as a breakthrough in addressing divides | major breakthrough, scientific breakthrough |

| financial inclusion | n | /faɪˈnænʃl ɪnˈkluːʒn/ | Hòa nhập tài chính | revolutionized financial inclusion | promote financial inclusion, financial inclusion strategies |

| functionality | n | /ˌfʌŋkʃəˈnæləti/ | Chức năng | This functionality gap means that… | limited functionality, core functionality |

| disparities | n | /dɪˈspærətiz/ | Sự chênh lệch, bất bình đẳng | these disparities contributed to learning loss | income disparities, reduce disparities |

| pedagogical | adj | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkl/ | Thuộc về sư phạm | embedded within pedagogical frameworks | pedagogical approach, pedagogical methods |

| algorithmic bias | n | /ˌælɡəˈrɪðmɪk ˈbaɪəs/ | Thiên kiến thuật toán | concerns regarding algorithmic bias | address algorithmic bias, algorithmic bias in AI |

| adaptive | adj | /əˈdæptɪv/ | Có khả năng thích nghi | Adaptive learning platforms adjust content | adaptive technology, adaptive system |

| marginalized | adj | /ˈmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪzd/ | Bị gạt ra ngoài lề | prove less effective for marginalized populations | marginalized communities, marginalized groups |

| co-design | n | /kəʊ dɪˈzaɪn/ | Đồng thiết kế | co-design processes involving community members | co-design approach, co-design workshops |

| sustainable | adj | /səˈsteɪnəbl/ | Bền vững | A sustainable approach to digital inclusion | sustainable development, sustainable practices |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| epistemological | adj | /ɪˌpɪstɪməˈlɒdʒɪkl/ | Thuộc về nhận thức luận | undergone considerable epistemological evolution | epistemological framework, epistemological assumptions |

| multifaceted | adj | /ˌmʌltiˈfæsɪtɪd/ | Nhiều mặt, đa diện | as a multifaceted phenomenon | multifaceted problem, multifaceted approach |

| ubiquitous | adj | /juːˈbɪkwɪtəs/ | Phổ biến khắp nơi | as ubiquitous computing reshapes | ubiquitous technology, ubiquitous presence |

| datafication | n | /ˌdeɪtəfɪˈkeɪʃn/ | Sự chuyển đổi dữ liệu | ubiquitous computing and datafication | datafication of society, datafication process |

| intersectionality | n | /ˌɪntəˌsekʃəˈnæləti/ | Tính giao thoa (của các yếu tố bất bình đẳng) | Intersectionality theory offers analytical purchase | intersectionality framework, intersectionality approach |

| asymmetries | n | /eɪˈsɪmətriz/ | Sự bất cân xứng | fundamental questions about power asymmetries | power asymmetries, information asymmetries |

| surveillance capitalism | n | /səˈveɪləns ˈkæpɪtəlɪzm/ | Chủ nghĩa tư bản giám sát | business models predicated on surveillance capitalism | surveillance capitalism era, surveillance capitalism model |

| extractive | adj | /ɪkˈstræktɪv/ | Mang tính khai thác | This extractive model disproportionately affects | extractive industries, extractive practices |

| opacity | n | /əʊˈpæsəti/ | Tính mờ đục, không minh bạch | The opacity of algorithmic decision-making | opacity of processes, increase opacity |

| proprietary | adj | /prəˈpraɪətri/ | Thuộc quyền sở hữu, độc quyền | often protected as proprietary information | proprietary technology, proprietary software |

| telehealth | n | /ˈtelɪhelθ/ | Chăm sóc sức khỏe từ xa | Telehealth services transitioned to necessities | telehealth services, telehealth platforms |

| ideological | adj | /ˌaɪdiəˈlɒdʒɪkl/ | Thuộc về tư tưởng | reflecting differing ideological orientations | ideological differences, ideological framework |

| capital-enhancing | adj | /ˈkæpɪtl ɪnˈhɑːnsɪŋ/ | Nâng cao năng lực | Capital-enhancing uses of technology | capital-enhancing activities, capital-enhancing investments |

| feedback loops | n | /ˈfiːdbæk luːps/ | Vòng lặp phản hồi | creating feedback loops where disadvantage persists | positive feedback loops, negative feedback loops |

| holistic | adj | /həˈlɪstɪk/ | Toàn diện, tổng thể | requires holistic interventions | holistic approach, holistic view |

| democratizing | adj | /dɪˈmɒkrətaɪzɪŋ/ | Dân chủ hóa | the democratizing potential of technology | democratizing access, democratizing education |

| obsolete | adj | /ˈɒbsəliːt/ | Lỗi thời | rendering previous skills obsolete | become obsolete, obsolete technology |

| inclusive design | n | /ɪnˈkluːsɪv dɪˈzaɪn/ | Thiết kế toàn diện | inclusive design processes that center needs | inclusive design principles, inclusive design approach |

Kết bài

Chủ đề “The Role Of Technology In Addressing The Digital Divide” không chỉ phổ biến trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh một vấn đề cấp thiết của xã hội toàn cầu hiện nay. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được luyện tập với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần, từ việc giới thiệu khái niệm cơ bản về khoảng cách số, đến phân tích các nghịch lý của giải pháp công nghệ, và cuối cùng là những thảo luận học thuật sâu rộng về công bằng số trong thời đại tính toán phổ biến.

Bộ đề thi đã cung cấp đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng bài khác nhau, giúp bạn làm quen với đa dạng các kỹ thuật làm bài cần thiết cho kỳ thi thực tế. Phần đáp án chi tiết không chỉ cho bạn biết câu trả lời đúng mà còn giải thích cách xác định thông tin, paraphrase và áp dụng chiến lược đọc hiểu hiệu quả.

Bảng từ vựng tổng hợp hơn 40 từ và cụm từ quan trọng theo từng passage sẽ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ vựng học thuật, đặc biệt trong lĩnh vực công nghệ và xã hội học – những chủ đề thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS. Hãy học kỹ các collocations và cách sử dụng những từ này trong ngữ cảnh thực tế.

Để đạt kết quả tốt nhất, bạn nên làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật (60 phút liên tục), sau đó dành thời gian xem lại đáp án và phân tích những câu sai để hiểu rõ lỗi của mình. Thực hành đều đặn với các đề thi mẫu chất lượng như thế này sẽ giúp bạn tự tin hơn và đạt band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading.