Mở bài

Trong bối cảnh toàn cầu hóa giáo dục ngày càng phát triển, chủ đề “Cultural Adaptation In International Education Systems” (Thích nghi văn hóa trong hệ thống giáo dục quốc tế) đã trở thành một trong những đề tài phổ biến và quan trọng trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Chủ đề này thường xuyên xuất hiện dưới nhiều góc độ khác nhau: từ trải nghiệm của du học sinh, sự điều chỉnh phương pháp giảng dạy, đến những thách thức về giao tiếp liên văn hóa trong môi trường học thuật.

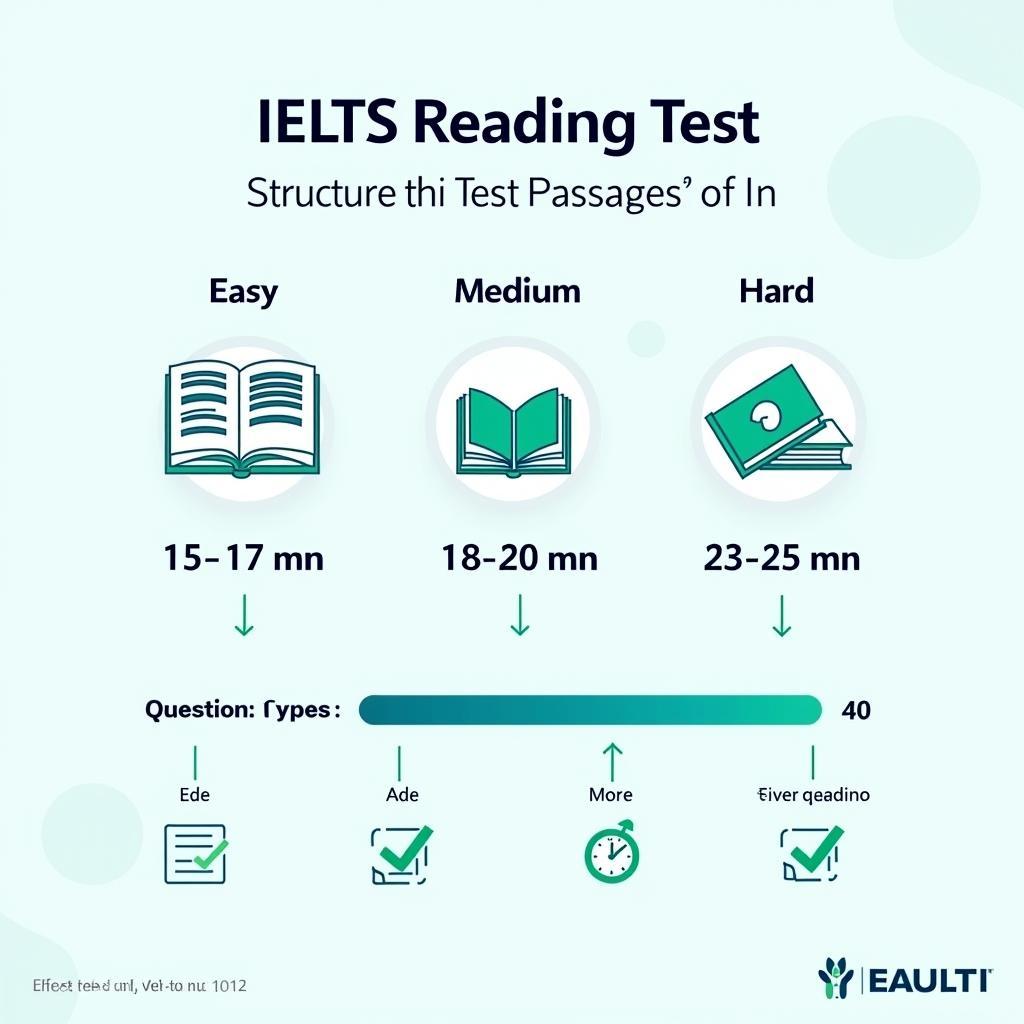

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh gồm 3 passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như thi thật. Bạn sẽ được thực hành với các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và nhiều dạng khác. Mỗi câu hỏi đều có đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cặn kẽ, giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách xác định thông tin và áp dụng kỹ thuật paraphrase hiệu quả.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, mang đến trải nghiệm luyện tập chân thực nhất để bạn tự tin bước vào phòng thi.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test là một phần thi quan trọng trong kỳ thi IELTS Academic, đánh giá khả năng đọc hiểu và xử lý thông tin học thuật của thí sinh. Bài thi kéo dài 60 phút và bao gồm 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó Easy)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó Medium)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó Hard)

Lưu ý rằng không có thời gian bổ sung để chép đáp án vào Answer Sheet, vì vậy bạn cần quản lý thời gian thật chặt chẽ và ghi đáp án trực tiếp trong quá trình làm bài.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến và quan trọng nhất:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hoặc không được đề cập

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề phù hợp với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào chỗ trống trong đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Information – Xác định đoạn văn chứa thông tin cụ thể

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Journey of International Students

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Every year, millions of students leave their home countries to pursue higher education in foreign lands. This phenomenon, known as international student mobility, has grown dramatically over the past three decades. Students from Asia, particularly China, India, and South Korea, make up the largest proportion of these mobile learners, with many choosing destinations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada.

The decision to study abroad is rarely simple. Students must consider numerous factors including the quality of education, career prospects, language requirements, and perhaps most importantly, their ability to adapt to a new culture. While the academic benefits are often clear, the personal challenges can be substantial. Many international students experience what researchers call ‘culture shock’ – a feeling of disorientation when exposed to an unfamiliar way of life.

Dr. Sarah Mitchell, a professor of international education at Oxford University, explains: “Culture shock typically occurs in stages. Initially, students feel excited and fascinated by everything new. Then, after a few weeks or months, they may feel frustrated and homesick as the differences between their home culture and the host culture become more apparent. This is the critical period when many students struggle.”

The educational environment itself presents significant challenges. Teaching styles vary considerably across cultures. In many Western universities, students are expected to participate actively in class discussions, challenge professors’ ideas, and work independently. This contrasts sharply with educational systems in countries where teachers are viewed as ultimate authorities and students are expected to listen and memorize rather than question and debate.

Language barriers compound these difficulties. Even students with strong English test scores often find themselves struggling to understand colloquial expressions, academic jargon, or regional accents. A study conducted by the International Education Association found that 67% of international students reported difficulties understanding lectures during their first semester, and 58% felt reluctant to speak up in class due to concerns about their accent or grammar.

Social integration represents another major challenge. Making friends with domestic students can be difficult, as cultural differences in communication styles, humor, and social norms create invisible barriers. Many international students find themselves socializing primarily within their own ethnic communities, which provides comfort but can limit their cultural immersion and language development.

Despite these challenges, most international students successfully adapt over time. Universities have increasingly recognized the need to provide comprehensive support services. These typically include orientation programs, language support classes, cultural adjustment workshops, and peer mentoring schemes. Some institutions have introduced “buddy systems” where domestic students are paired with international newcomers to help them navigate both academic and social aspects of university life.

The process of adaptation also depends heavily on the student’s own attitude and strategies. Research shows that students who actively seek out interaction with people from different cultures, maintain a positive attitude toward challenges, and view difficulties as learning opportunities tend to adapt more quickly and successfully. Dr. James Chen, who researches cross-cultural adaptation, notes: “Students who engage with the host culture while maintaining connections to their home culture tend to develop what we call ‘bicultural competence’ – the ability to function effectively in both cultural contexts.”

The benefits of successful cultural adaptation extend far beyond the university years. International students who navigate these challenges develop valuable skills including flexibility, intercultural communication, resilience, and global awareness. These competencies are increasingly valued by employers in our interconnected world. A survey of multinational corporations found that 84% of executives considered cross-cultural experience an important criterion when hiring graduates.

Furthermore, the experience of cultural adaptation often leads to personal growth and self-discovery. Students report increased confidence, independence, and a broader worldview. Many describe their international education as a transformative experience that fundamentally changed how they see themselves and the world around them.

Universities themselves benefit from having a diverse international student body. Domestic students gain exposure to different perspectives and cultures without leaving their home country. Classroom discussions become richer and more varied when students from multiple cultural backgrounds contribute their unique viewpoints. This diversity also encourages all students to question their assumptions and develop more nuanced understanding of global issues.

Looking forward, experts predict that international student mobility will continue to grow, albeit with some shifts in patterns and destinations. Emerging economies are investing heavily in their higher education systems, potentially becoming new popular destinations. Additionally, digital technology is creating new forms of international education, including online degrees and virtual exchange programs, which may complement or partially replace traditional study-abroad experiences.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

1. According to the passage, the largest group of international students comes from:

- A. Europe

- B. Asia

- C. South America

- D. Africa

2. Dr. Sarah Mitchell describes culture shock as something that:

- A. happens immediately upon arrival

- B. only affects weak students

- C. occurs in different stages

- D. can be completely avoided

3. The teaching style in Western universities is characterized by:

- A. strict memorization requirements

- B. respect for teachers as absolute authorities

- C. active student participation and questioning

- D. minimal interaction between students and professors

4. What percentage of international students struggled to understand lectures in their first semester?

- A. 58%

- B. 67%

- C. 84%

- D. The passage does not specify

5. According to research, students adapt more successfully when they:

- A. avoid their home culture entirely

- B. only socialize with domestic students

- C. engage with both host and home cultures

- D. focus exclusively on academic work

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Write TRUE if the statement agrees with the information, FALSE if the statement contradicts the information, or NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this.

6. All international students experience culture shock at the same intensity.

7. Language difficulties are limited to students with poor English test scores.

8. Universities now provide more support services for international students than in the past.

9. International students typically pay higher tuition fees than domestic students.

Questions 10-13: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

International students face multiple challenges when studying abroad. Beyond academic demands, they must deal with 10. __ and learn to interact in a new cultural environment. Many find it difficult to make friends with 11. __ due to cultural differences. However, universities now offer various 12. __ including orientation programs and mentoring. Students who successfully adapt develop 13. __, which is highly valued by future employers.

PASSAGE 2 – Pedagogical Approaches in Multicultural Classrooms

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The increasing cultural diversity in educational institutions worldwide has prompted educators and researchers to reconsider traditional teaching methodologies. The challenge lies not merely in accommodating students from different backgrounds, but in creating pedagogical frameworks that leverage this diversity as an educational asset rather than viewing it as a complication to be managed.

A. Professor Linda Hartmann, director of the International Teaching Excellence Centre in Toronto, argues that the conventional Western pedagogical model – emphasizing individual achievement, critical thinking, and student-centered learning – often conflicts with the educational values many international students bring from their home countries. “Students from Confucian heritage cultures, for instance, typically come from systems that emphasize collective harmony, respect for authority, and knowledge transmission from teacher to student. When these students encounter the expectation to openly challenge ideas or engage in debate, it can create significant cognitive dissonance,” she explains.

B. This cultural clash extends beyond classroom dynamics to fundamental assumptions about the nature of knowledge itself. Western educational philosophy generally promotes the idea that knowledge is constructed through critical analysis and debate, whereas many Asian educational traditions view knowledge as something to be acquired from recognized authorities and refined through diligent study. Neither approach is inherently superior; rather, they represent different epistemological traditions that have evolved within distinct cultural contexts.

C. The concept of ‘culturally responsive teaching’ has emerged as one response to these challenges. This approach requires educators to develop cultural competence – an understanding of how culture influences learning styles, communication patterns, and classroom behavior. Dr. Marcus Thompson, whose research focuses on intercultural pedagogy, suggests that effective teachers in multicultural classrooms must become “cultural translators,” helping students understand not just the content being taught, but the cultural assumptions underlying different approaches to learning and knowledge creation.

D. Several universities have implemented innovative programs to bridge these cultural divides. The University of Melbourne’s ‘Intercultural Learning Programme’ trains both staff and students in cross-cultural communication strategies. Similarly, the Technical University of Munich has introduced ‘tandem learning’ arrangements where domestic and international students work together on projects, explicitly discussing their different approaches to problem-solving and collaboration. These initiatives recognize that cultural adaptation should not be unidirectional – that is, solely the responsibility of international students. Rather, intercultural competence should be developed by all members of the academic community.

E. Assessment methods represent another critical area where cultural factors come into play. Traditional Western assessment often emphasizes individual performance, originality, and the ability to synthesize information and present independent arguments. However, students from cultures that prioritize collective achievement may struggle with assessments that pit them against their peers. Moreover, concepts like ‘academic integrity’ and plagiarism can be culturally constructed in ways that aren’t immediately obvious to students from different educational backgrounds. What Western academia considers plagiarism might be viewed in other cultures as appropriate respect for authoritative sources.

F. The rise of collaborative learning approaches offers promising pathways for inclusive education. Group projects, peer teaching, and cooperative problem-solving can accommodate diverse learning preferences while building intercultural skills. However, research by Dr. Yuki Tanaka at Kyoto University warns against assuming that group work automatically promotes cultural integration. Without careful facilitation, multicultural groups may experience communication difficulties, unequal participation, and reinforcement of stereotypes. “The key,” Dr. Tanaka argues, “is structured collaboration where roles are clear, cultural differences are openly acknowledged, and students receive guidance on effective intercultural teamwork.”

G. Technology is playing an increasingly important role in supporting culturally diverse learners. Learning management systems can provide materials in multiple formats, accommodating different learning preferences. Automated translation tools, while imperfect, can help students access content in their native language when wrestling with complex concepts. Discussion forums may offer a less intimidating environment for students hesitant to speak up in class, allowing them time to formulate responses and reducing the pressure of real-time linguistic performance.

H. Some scholars question whether the emphasis on cultural differences might inadvertently promote stereotyping and essentialism. Professor Amanda Whitfield cautions against assuming that all students from a particular country or region share identical learning preferences or cultural values. “Culture certainly influences education, but so do individual personality, prior educational experiences, socioeconomic background, and many other factors. We must avoid cultural determinism – the idea that culture completely dictates how someone learns,” she states. Research supports this nuanced view, showing considerable individual variation within cultural groups alongside general patterns.

I. The concept of ‘third space pedagogy’ represents an emerging framework for multicultural education. Rather than asking students to choose between their home culture’s educational values and those of the host institution, this approach encourages the creation of new, hybrid learning environments that draw on multiple cultural traditions. Students are invited to become ‘knowledge brokers’, actively contributing their cultural perspectives to enrich the learning experience for everyone. This transforms cultural diversity from a challenge to be managed into a pedagogical resource that enhances educational outcomes for all students.

Looking ahead, preparing students for an interconnected world requires more than simply managing cultural differences in the classroom. It demands a fundamental reconceptualization of education itself – one that views intercultural competence not as a supplementary skill but as a core educational outcome. As universities continue to internationalize, the development of truly inclusive pedagogical practices will be essential not just for international student success, but for equipping all graduates with the capabilities they need to thrive in global professional environments.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-19: Matching Headings

The passage has nine paragraphs, A-I. Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. The risks of oversimplifying cultural influences

ii. Technological solutions for diverse classrooms

iii. Conflicting educational philosophies

iv. Creating hybrid learning spaces

v. Assessment challenges across cultures

vi. The need for mutual adaptation

vii. Problems with collaborative learning

viii. Different concepts of knowledge

ix. Structured approaches to group work

x. The importance of cultural understanding in teaching

14. Paragraph A

15. Paragraph C

16. Paragraph E

17. Paragraph F

18. Paragraph H

19. Paragraph I

Questions 20-23: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in the passage? Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

20. Western educational approaches are more effective than Asian educational traditions.

21. Cultural adaptation in education should involve both international and domestic students.

22. Group work always leads to better cultural understanding among students.

23. Universities should prioritize developing students’ intercultural competence.

Questions 24-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Educators face significant challenges in multicultural classrooms due to different 24. __ about learning and knowledge. While some cultures emphasize individual achievement, others value 25. __. The concept of 26. __ offers a promising solution by creating learning environments that incorporate multiple cultural traditions rather than favoring one approach.

PASSAGE 3 – Institutional Transformation and the Internationalization Paradigm

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The internationalization of higher education represents one of the most significant transformations in the contemporary academic landscape, yet the conceptual frameworks underlying this phenomenon remain contested terrain. While early models of internationalization focused primarily on student mobility and revenue generation, contemporary scholarship increasingly recognizes that genuine internationalization requires profound institutional change that extends far beyond merely recruiting international students or establishing overseas campuses. This shift reflects a growing understanding that internationalization, properly conceived, entails the integration of international, intercultural, and global dimensions into the purpose, functions, and delivery of higher education.

The dominant discourse surrounding internationalization has historically been characterized by what critics term ‘neo-liberal instrumentalism’ – an approach that views international students primarily as economic assets and internationalization as a strategy for enhancing institutional prestige and competitiveness in global rankings. Dr. Rajesh Sharma, whose critical analysis of internationalization policies has influenced policy debates globally, argues that this paradigm reduces education to a tradable commodity and positions students as consumers in an educational marketplace. “This commodification fundamentally distorts the educational mission,” Sharma contends, “transforming what should be a transformative intercultural learning experience into a transactional relationship focused on credentials and career outcomes rather than genuine intercultural understanding and global citizenship.”

Alternative conceptualizations have emerged that challenge this market-oriented model. The concept of ‘internationalization at home’ recognizes that the majority of students will never study abroad and emphasizes the integration of international and intercultural dimensions into the domestic learning environment for all students. This approach seeks to democratize the benefits of internationalization, ensuring that intercultural competence development is not limited to the privileged minority with resources to study abroad. Professor Margaret Chen’s longitudinal research demonstrates that well-designed internationalization at home initiatives can develop intercultural sensitivity and global perspectives comparable to those achieved through study abroad, provided they involve sustained engagement rather than superficial exposure to cultural diversity.

The curriculum internationalization agenda presents particularly complex challenges. Superficial approaches – adding a few international case studies to existing courses or offering modules on “doing business in China” – fail to address the fundamental epistemological questions that genuine internationalization must confront. Whose knowledge is privileged in the curriculum? What assumptions about the nature of valid knowledge are embedded in disciplinary traditions? How can curricula acknowledge and incorporate diverse knowledge systems, including indigenous knowledge traditions that have been historically marginalized in Western academic institutions?

These questions have given rise to calls for ‘epistemic pluralism’ in internationalized curricula – recognition that different cultures have developed distinct ways of knowing, modes of inquiry, and standards of evidence that may be equally valid within their contexts. However, implementing this principle proves enormously challenging. Dr. Amina Hassan, whose work examines decolonization in higher education, notes the inherent power asymmetries that shape these discussions: “When we talk about integrating diverse knowledge systems, we’re still operating within institutional structures, disciplinary frameworks, and pedagogical conventions that are fundamentally Western in origin. True epistemic justice would require more radical transformation than most institutions are prepared to undertake.”

The assessment of intercultural learning outcomes presents another significant challenge for internationalized institutions. Traditional assessment methods often fail to capture the complex, developmental nature of intercultural competence. Students may demonstrate knowledge about different cultures (the cognitive dimension) while lacking the affective sensitivity or behavioral skills necessary for effective intercultural interaction. The Intercultural Development Inventory and similar instruments attempt to measure these multidimensional aspects of intercultural competence, but questions remain about whether such competencies can be meaningfully assessed using standardized instruments, given their inherently context-dependent and relational nature.

Furthermore, the very concept of ‘culture’ deployed in internationalization discourse has come under critical scrutiny. The tendency to treat national cultures as bounded, homogeneous entities – thinking of ‘Chinese culture’ or ‘Brazilian culture’ as if all individuals from these nations share identical cultural characteristics – has been widely criticized as promoting essentialist stereotypes. Contemporary intercultural theory emphasizes that culture is fluid, contested, and multiply layered; individuals simultaneously inhabit multiple cultural identities based on nationality, ethnicity, religion, profession, generation, and numerous other factors. Effective internationalization strategies must therefore avoid reductive cultural categorizations while still acknowledging that cultural differences meaningfully impact educational experiences.

The organizational change required for genuine internationalization is often underestimated. Research by Beelen and Jones identifies several institutional barriers: ethnocentric assumptions embedded in institutional culture, resistance from faculty who view internationalization as peripheral to their disciplinary focus, inadequate professional development to equip staff with intercultural teaching competencies, and structural silos that prevent the integrated, institution-wide approach that effective internationalization requires. Their findings suggest that internationalization often remains a marginal initiative championed by specific departments or individuals rather than achieving the comprehensive institutional transformation that advocates envision.

The financial sustainability of internationalization initiatives poses additional challenges, particularly for institutions that have come to depend on international student fees to subsidize domestic operations. This revenue dependence creates problematic incentives, potentially encouraging institutions to lower admission standards for full-fee-paying international students or to avoid making demands on international students that might affect satisfaction ratings and future enrollment. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly revealed the vulnerabilities of this model, as border closures and travel restrictions precipitated financial crises at institutions heavily reliant on international student revenue.

Looking forward, several scholars argue for reconceptualizing internationalization around principles of solidarity, reciprocity, and mutual benefit rather than competition and commercial advantage. The ‘cooperative internationalization’ framework proposed by De Wit emphasizes partnerships based on shared academic values and complementary strengths rather than hierarchical relationships where prestigious Western institutions extract talent and resources from less powerful partners in the global South. Similarly, the concept of ‘ethical internationalization’ calls for transparency about the purposes and impacts of internationalization activities, attention to power dynamics in international partnerships, and accountability for internationalization’s effects on equity both within and between institutions.

Some emerging initiatives exemplify these alternative approaches. The African Research Universities Alliance promotes intra-African academic collaboration and the development of research capacity rooted in African contexts and priorities. The Talloires Network connects universities worldwide around civic engagement commitments, fostering international collaboration focused on addressing global challenges rather than competing for market position. These networks suggest possibilities for internationalization organized around shared purpose and collective benefit rather than individual institutional advancement.

The ultimate question confronting higher education internationalization is perhaps philosophical: What is internationalization for? If the purpose is primarily economic – generating revenue, enhancing prestige, or providing credentials that advantage individuals in labor markets – then current market-oriented approaches may be adequate. However, if internationalization is fundamentally about education in its deepest sense – developing capabilities for understanding across differences, fostering global awareness and responsibility, and preparing graduates to address transnational challenges – then much more profound transformation is required. The pathway chosen will significantly influence not only higher education but also our collective capacity to navigate an increasingly interdependent yet conflicted world.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

27. According to the passage, early models of internationalization primarily focused on:

- A. developing intercultural competence

- B. student mobility and financial benefits

- C. curriculum transformation

- D. faculty development

28. Dr. Rajesh Sharma criticizes the neo-liberal approach to internationalization because it:

- A. is too expensive for most institutions

- B. reduces education to a commercial transaction

- C. excludes domestic students from benefits

- D. requires too much institutional change

29. ‘Internationalization at home’ aims to:

- A. replace study abroad programs entirely

- B. make intercultural learning accessible to all students

- C. reduce costs for universities

- D. eliminate the need for international students

30. Dr. Amina Hassan argues that achieving epistemic justice is difficult because:

- A. students resist learning about other cultures

- B. there are too many different knowledge systems

- C. institutional structures remain fundamentally Western

- D. faculty lack adequate training

31. The concept of ‘cooperative internationalization’ emphasizes:

- A. competition between institutions

- B. financial sustainability

- C. partnerships based on mutual benefit

- D. standardized assessment methods

Questions 32-36: Matching Information

Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter, A-L. You may use any letter more than once.

32. A description of organizations promoting alternative internationalization models

33. Criticism of how culture is conceptualized in internationalization discussions

34. Discussion of difficulties in measuring intercultural learning

35. Explanation of financial vulnerabilities in current internationalization approaches

36. Reference to the need for fundamental changes in curriculum content

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What type of learning experience does genuine internationalization aim to provide, according to Sharma?

38. What institutional problem prevents integrated internationalization, according to Beelen and Jones?

39. What event exposed the financial risks of depending on international student fees?

40. According to the passage, what type of challenges should internationalization help graduates address?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- C

- C

- B

- C

- NOT GIVEN

- FALSE

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- culture shock

- domestic students

- support services

- cross-cultural experience / intercultural communication

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- iii

- x

- v

- ix

- i

- iv

- NO

- YES

- NO

- YES

- cultural assumptions / epistemological traditions

- collective harmony

- third space pedagogy

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- B

- B

- C

- C

- L (paragraph 12)

- J (paragraph 7)

- I (paragraph 6)

- K (paragraph 9)

- G (paragraph 4)

- transformative intercultural

- structural silos

- COVID-19 pandemic

- transnational challenges

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: largest group, international students

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “Students from Asia, particularly China, India, and South Korea, make up the largest proportion of these mobile learners.” Đáp án B (Asia) là chính xác. Các đáp án khác không được đề cập là nhóm lớn nhất.

Câu 2: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Dr. Sarah Mitchell, culture shock

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Dr. Mitchell giải thích “Culture shock typically occurs in stages,” sau đó mô tả các giai đoạn khác nhau. Đáp án C chính xác. Đáp án A sai vì culture shock không xảy ra ngay lập tức, D sai vì không thể hoàn toàn tránh được.

Câu 6: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all international students, same intensity

- Giải thích: Bài đọc đề cập culture shock xảy ra nhưng không nói liệu tất cả sinh viên có trải nghiệm ở cùng mức độ hay không. Không có thông tin để xác nhận hoặc bác bỏ.

Câu 7: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: language difficulties, poor English test scores

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “Even students with strong English test scores often find themselves struggling,” chứng tỏ khó khăn về ngôn ngữ không chỉ giới hạn ở sinh viên có điểm test kém. Câu này mâu thuẫn với thông tin trong bài nên là FALSE.

Câu 8: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: universities, more support services

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Universities have increasingly recognized the need to provide comprehensive support services” cho thấy các trường đã tăng cường dịch vụ hỗ trợ so với trước đây.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: iii

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Paragraph A

- Giải thích: Đoạn A thảo luận về sự xung đột giữa Western pedagogical model và giá trị giáo dục mà sinh viên quốc tế mang theo, tương ứng với heading “Conflicting educational philosophies.”

Câu 20: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí: Paragraph B

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “Neither approach is inherently superior” khi so sánh các phương pháp giáo dục Western và Asian. Điều này trực tiếp mâu thuẫn với statement rằng Western approaches hiệu quả hơn.

Câu 21: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí: Paragraph D

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nói rõ “cultural adaptation should not be unidirectional” và “intercultural competence should be developed by all members of the academic community,” thể hiện quan điểm của tác giả rằng cả sinh viên quốc tế và nội địa đều cần thích nghi.

Câu 22: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí: Paragraph F

- Giải thích: Dr. Tanaka cảnh báo “against assuming that group work automatically promotes cultural integration” và nêu các vấn đề có thể xảy ra. Điều này mâu thuẫn với statement.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: early models, internationalization

- Vị trí: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Early models of internationalization focused primarily on student mobility and revenue generation” khớp với đáp án B. Các đáp án khác là các khái niệm xuất hiện sau này.

Câu 30: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Dr. Amina Hassan, epistemic justice

- Vị trí: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: Dr. Hassan nói “we’re still operating within institutional structures, disciplinary frameworks, and pedagogical conventions that are fundamentally Western in origin,” giải thích tại sao epistemic justice khó đạt được.

Câu 37: transformative intercultural

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Từ khóa: genuine internationalization, learning experience, Sharma

- Vị trí: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Sharma nói về “transformative intercultural learning experience” là những gì internationalization thực sự nên mang lại, đối lập với mô hình transactional.

Câu 38: structural silos

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Từ khóa: institutional problem, integrated internationalization, Beelen and Jones

- Vị trí: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: Nghiên cứu của Beelen và Jones xác định “structural silos” như một rào cản ngăn cản “integrated, institution-wide approach.”

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| higher education | noun phrase | /ˈhaɪər edʒuˈkeɪʃn/ | giáo dục đại học | pursue higher education in foreign lands | pursue/access higher education |

| adapt | verb | /əˈdæpt/ | thích nghi, điều chỉnh | their ability to adapt to a new culture | adapt to changes/circumstances |

| culture shock | noun | /ˈkʌltʃə ʃɒk/ | sốc văn hóa | experience what researchers call culture shock | experience/suffer culture shock |

| frustrated | adjective | /frʌˈstreɪtɪd/ | bực bội, thất vọng | they may feel frustrated and homesick | feel frustrated with/by |

| challenge | verb/noun | /ˈtʃælɪndʒ/ | thách thức, thử thách | challenge professors’ ideas | face/pose a challenge |

| ultimate authority | noun phrase | /ˈʌltɪmət ɔːˈθɒrəti/ | thẩm quyền tuyệt đối | teachers are viewed as ultimate authorities | recognize/accept as authority |

| colloquial expressions | noun phrase | /kəˈləʊkwiəl ɪkˈspreʃnz/ | cách diễn đạt thông tục | understand colloquial expressions | use/understand colloquial language |

| reluctant | adjective | /rɪˈlʌktənt/ | miễn cưỡng, ngần ngại | felt reluctant to speak up | reluctant to do something |

| domestic students | noun phrase | /dəˈmestɪk ˈstjuːdnts/ | sinh viên nội địa | making friends with domestic students | domestic/international students |

| cultural immersion | noun phrase | /ˈkʌltʃərəl ɪˈmɜːʃn/ | hòa nhập văn hóa | limit their cultural immersion | cultural immersion program |

| comprehensive | adjective | /ˌkɒmprɪˈhensɪv/ | toàn diện, đầy đủ | provide comprehensive support services | comprehensive approach/coverage |

| resilience | noun | /rɪˈzɪliəns/ | khả năng phục hồi | develop valuable skills including resilience | build/demonstrate resilience |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pedagogical | adjective | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkl/ | thuộc về sư phạm | creating pedagogical frameworks | pedagogical approach/method |

| cognitive dissonance | noun phrase | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˈdɪsənəns/ | mâu thuẫn nhận thức | create significant cognitive dissonance | experience cognitive dissonance |

| epistemological | adjective | /ɪˌpɪstəməˈlɒdʒɪkl/ | nhận thức luận | different epistemological traditions | epistemological perspective/question |

| culturally responsive | adjective phrase | /ˈkʌltʃərəli rɪˈspɒnsɪv/ | nhạy cảm văn hóa | culturally responsive teaching | culturally responsive pedagogy |

| cultural competence | noun phrase | /ˈkʌltʃərəl ˈkɒmpɪtəns/ | năng lực văn hóa | develop cultural competence | develop/demonstrate cultural competence |

| intercultural pedagogy | noun phrase | /ˌɪntəˈkʌltʃərəl ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒi/ | sư phạm liên văn hóa | research focuses on intercultural pedagogy | intercultural communication/competence |

| unidirectional | adjective | /ˌjuːnɪdəˈrekʃənl/ | một chiều | should not be unidirectional | unidirectional approach/flow |

| synthesize | verb | /ˈsɪnθəsaɪz/ | tổng hợp | ability to synthesize information | synthesize information/data |

| plagiarism | noun | /ˈpleɪdʒərɪzəm/ | đạo văn | concepts like plagiarism | commit/avoid plagiarism |

| collaborative learning | noun phrase | /kəˈlæbərətɪv ˈlɜːnɪŋ/ | học tập hợp tác | collaborative learning approaches | collaborative learning environment |

| stereotyping | noun | /ˈsteriətaɪpɪŋ/ | định kiến, rập khuôn | promote stereotyping and essentialism | avoid/combat stereotyping |

| hybrid | adjective | /ˈhaɪbrɪd/ | lai, kết hợp | hybrid learning environments | hybrid model/approach |

| reconceptualization | noun | /riːkənˌseptʃuəlaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | tái khái niệm hóa | fundamental reconceptualization of education | require reconceptualization |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conceptual frameworks | noun phrase | /kənˈseptʃuəl ˈfreɪmwɜːks/ | khung khái niệm | conceptual frameworks underlying this phenomenon | theoretical/conceptual framework |

| contested terrain | noun phrase | /kənˈtestɪd təˈreɪn/ | lãnh địa tranh cãi | remain contested terrain | contested issue/concept |

| neo-liberal | adjective | /ˌniːəʊ ˈlɪbərəl/ | tân tự do | neo-liberal instrumentalism | neo-liberal policies/ideology |

| commodification | noun | /kəˌmɒdɪfɪˈkeɪʃn/ | hàng hóa hóa | this commodification fundamentally distorts | commodification of education |

| democratize | verb | /dɪˈmɒkrətaɪz/ | dân chủ hóa | seeks to democratize the benefits | democratize access/opportunities |

| intercultural sensitivity | noun phrase | /ˌɪntəˈkʌltʃərəl ˌsensəˈtɪvəti/ | nhạy cảm liên văn hóa | develop intercultural sensitivity | cultural sensitivity/awareness |

| epistemic pluralism | noun phrase | /ɪˈpɪstɪmɪk ˈplʊərəlɪzəm/ | đa nguyên nhận thức | calls for epistemic pluralism | epistemic justice/diversity |

| decolonization | noun | /diːˌkɒlənaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | phi thực dân hóa | examines decolonization in higher education | decolonization of knowledge |

| power asymmetries | noun phrase | /ˈpaʊər eɪˈsɪmətriz/ | bất cân xứng quyền lực | inherent power asymmetries | power dynamics/imbalance |

| essentialist | adjective | /ɪˈsenʃəlɪst/ | bản chất luận | promoting essentialist stereotypes | essentialist view/approach |

| ethnocentric | adjective | /ˌeθnəʊˈsentrɪk/ | dân tộc trung tâm | ethnocentric assumptions | ethnocentric perspective/bias |

| reciprocity | noun | /ˌresɪˈprɒsəti/ | sự có đi có lại | principles of reciprocity | mutual reciprocity |

| transnational challenges | noun phrase | /trænzˈnæʃənl ˈtʃælɪndʒɪz/ | thách thức xuyên quốc gia | address transnational challenges | global/transnational issues |

| solidarity | noun | /ˌsɒlɪˈdærəti/ | đoàn kết | reconceptualizing around principles of solidarity | show/express solidarity |

| contested | adjective | /kənˈtestɪd/ | bị tranh cãi | culture is fluid and contested | contested concept/definition |

Kết bài

Chủ đề “Cultural adaptation in international education systems” không chỉ phổ biến trong IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh một vấn đề quan trọng và thiết thực trong thời đại toàn cầu hóa hiện nay. Qua ba passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, bạn đã được tiếp cận với đầy đủ các khía cạnh của chủ đề: từ trải nghiệm cá nhân của du học sinh, phương pháp giảng dạy trong lớp học đa văn hóa, cho đến các vấn đề phức tạp về thể chế và triết lý giáo dục.

Bộ đề thi mẫu này cung cấp 40 câu hỏi đa dạng với đầy đủ các dạng bài phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading, giúp bạn làm quen với format thi thật và rèn luyện kỹ năng xử lý các loại câu hỏi khác nhau. Phần đáp án chi tiết không chỉ cung cấp key answers mà còn giải thích tỉ mỉ cách tìm thông tin, nhận diện paraphrase và tránh các fallen traps phổ biến.

Đặc biệt, phần từ vựng được tổng hợp theo từng passage sẽ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ học thuật, hiểu cách sử dụng collocations tự nhiên và nâng cao khả năng đọc hiểu các bài viết phức tạp. Hãy xem đây không chỉ là một bài luyện tập mà là cơ hội để phát triển kỹ năng Reading toàn diện, tư duy phản biện và hiểu biết sâu sắc về một chủ đề toàn cầu quan trọng.

Chúc bạn luyện tập hiệu quả và đạt band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!