Trong những năm gần đây, chủ đề về sức khỏe tâm thần và các phương pháp điều trị tự nhiên ngày càng xuất hiện phổ biến trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Đặc biệt, đề tài về liệu pháp thiên nhiên (nature therapy) đã trở thành một xu hướng nổi bật trong các bài thi Cambridge IELTS từ quyển 14 trở đi. Chủ đề này không chỉ phản ánh sự quan tâm toàn cầu về sức khỏe tinh thần mà còn kết hợp nhiều khía cạnh khoa học, xã hội và môi trường – những yếu tố thường xuyên được đánh giá trong IELTS Academic Reading.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages có độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như thi thật. Bạn sẽ được thực hành với nhiều dạng câu hỏi phổ biến như True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và nhiều dạng khác. Mỗi câu hỏi đều có đáp án chính xác kèm giải thích chi tiết, giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách paraphrase và định vị thông tin trong bài đọc.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, với mục tiêu đạt band 6.5-8.0 trong phần Reading. Ngoài đề thi và đáp án, bạn còn được trang bị bộ từ vựng quan trọng theo từng passage, cùng các chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả được đúc kết từ kinh nghiệm giảng dạy thực tế.

Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

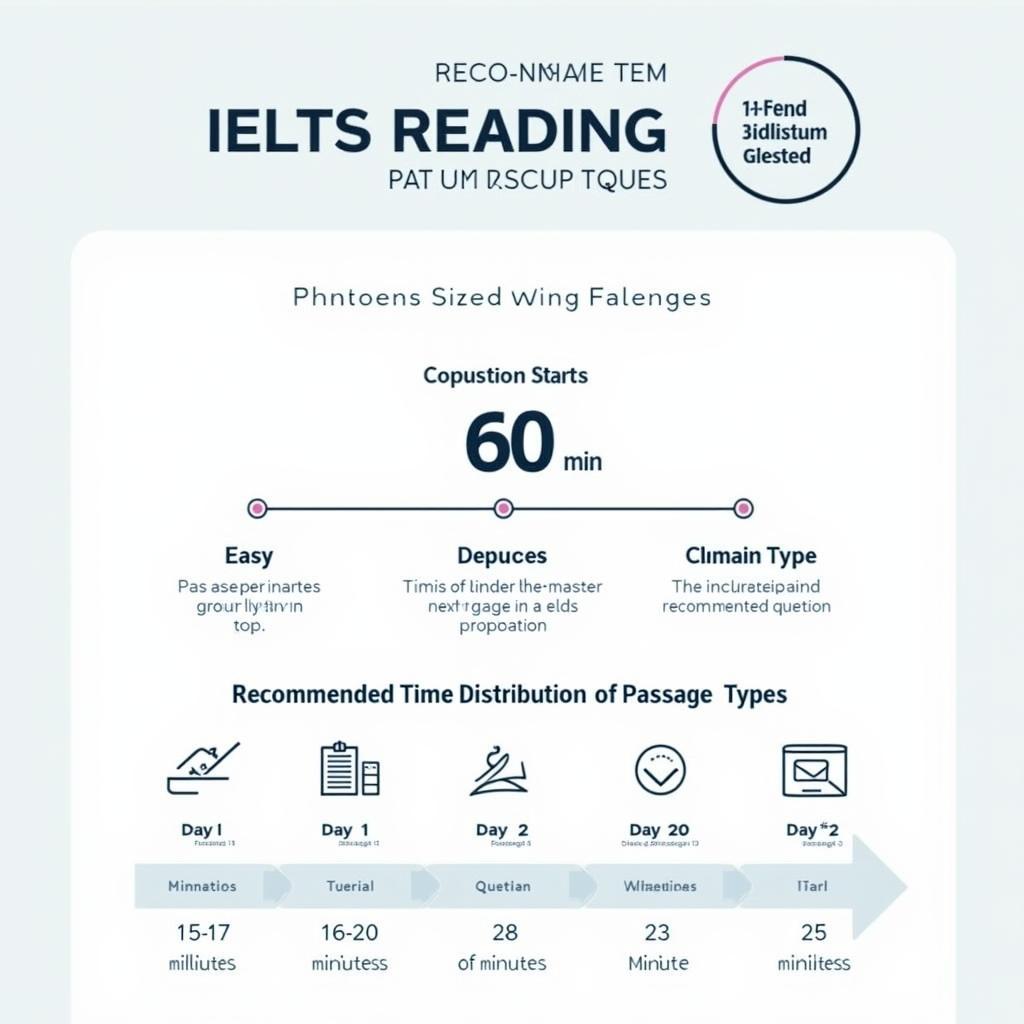

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Đây là bài thi đòi hỏi khả năng quản lý thời gian tốt và kỹ năng đọc hiểu sâu. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, và tổng số điểm sẽ được quy đổi thành band score từ 1-9.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1 (Easy): 15-17 phút – Dành cho việc “làm nóng” và ghi điểm dễ dàng

- Passage 2 (Medium): 18-20 phút – Cần tập trung hơn với từ vựng học thuật

- Passage 3 (Hard): 23-25 phút – Yêu cầu phân tích và suy luận cao

Lưu ý quan trọng: Bạn cần tự chuyển đáp án từ đề bài sang answer sheet trong thời gian 60 phút này. Không có thời gian bổ sung như phần Listening.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không được đề cập

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn tương ứng

- Matching Headings – Chọn tiêu đề phù hợp cho mỗi đoạn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thiện đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features – Nối các đặc điểm với danh mục

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời ngắn với giới hạn từ

Mỗi dạng câu hỏi yêu cầu kỹ năng đọc khác nhau, từ skimming (đọc lướt) đến scanning (đọc tìm kiếm) và reading for detail (đọc chi tiết).

Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading hiệu quả với kỹ thuật quản lý thời gian và chiến lược đọc hiểu

Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading hiệu quả với kỹ thuật quản lý thời gian và chiến lược đọc hiểu

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Nature’s Healing Power: An Introduction to Forest Bathing

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

In recent years, mental health awareness has become a global priority, with researchers and healthcare professionals exploring various therapeutic approaches beyond traditional medication and counseling. One practice that has gained significant attention is forest bathing, or “shinrin-yoku” in Japanese, which literally translates to “taking in the forest atmosphere.” This simple yet powerful concept involves spending time in natural forest environments to improve both physical and psychological well-being.

The origins of forest bathing can be traced back to Japan in the 1980s, when the Japanese government launched a national health program to encourage citizens to reconnect with nature. At that time, Japan was experiencing rapid urbanization and industrialization, which led to increased stress levels and various lifestyle-related diseases among the population. Medical professionals noticed a correlation between the decreasing amount of time people spent outdoors and the rising rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. This observation prompted scientists to investigate whether deliberate exposure to natural environments could serve as a preventive healthcare measure.

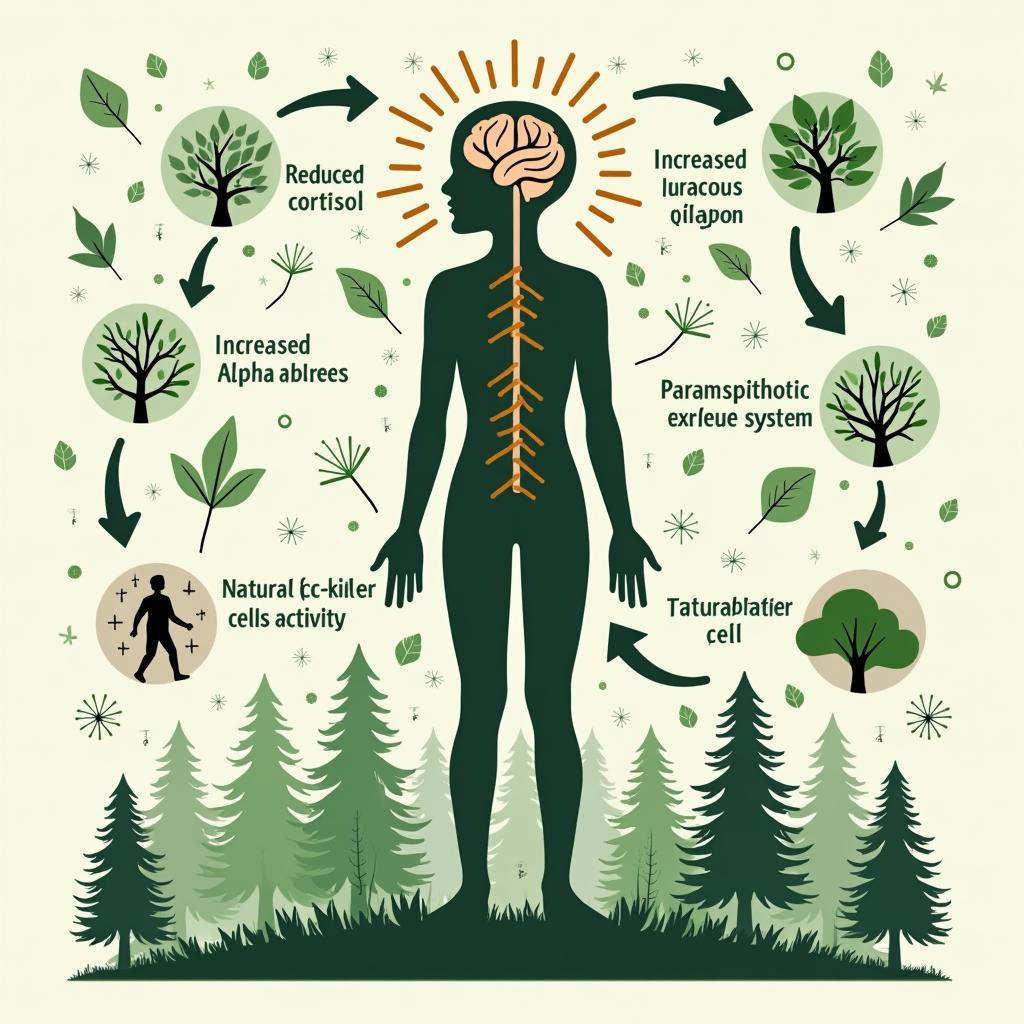

Dr. Qing Li, a prominent researcher at Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, has been at the forefront of studying the physiological effects of forest bathing. His research team has discovered that when people spend time in forests, their bodies undergo measurable positive changes. One of the most significant findings is the reduction in cortisol levels – cortisol being the primary stress hormone produced by the human body. In controlled studies, participants who engaged in a two-hour forest walk showed a 12.4% decrease in cortisol compared to those who walked in urban environments. Additionally, forest bathing has been shown to lower blood pressure, reduce heart rate variability, and improve overall cardiovascular health.

The therapeutic benefits of nature extend beyond physical measurements. Psychological assessments have revealed that forest bathing significantly improves mood states and reduces symptoms of anxiety and depression. Participants in various studies reported feeling more relaxed, energized, and mentally clear after spending time among trees. Some researchers attribute these effects to the concept of “biophilia” – the innate human tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life. This biological predisposition suggests that humans are naturally programmed to feel more at ease in natural settings, as our ancestors evolved in such environments over millions of years.

Another fascinating aspect of forest bathing involves phytoncides – organic compounds released by trees and plants as a defense mechanism against insects and diseases. When humans breathe in these airborne chemicals during forest walks, their immune systems receive a notable boost. Studies have shown that exposure to phytoncides increases the activity of natural killer (NK) cells, which are crucial components of the body’s defense against infections and cancer. In one experiment, participants who spent three days and two nights in a forest environment showed a 50% increase in NK cell activity, and this effect lasted for up to 30 days after the forest visit.

The practice of forest bathing is remarkably simple and accessible. Unlike intensive exercise programs or complex meditation techniques, it requires no special equipment or training. The key principle is to slow down and engage all five senses while walking through a forested area. Practitioners are encouraged to notice the colors and patterns of leaves, listen to bird songs and rustling branches, feel the texture of tree bark, smell the earthy forest scent, and even taste edible plants when safe to do so. This mindful approach to nature immersion helps create a state of relaxation and present-moment awareness.

As urban populations continue to grow worldwide, access to natural forest environments has become increasingly limited for many people. However, researchers have found that even small green spaces such as city parks, botanical gardens, or tree-lined streets can provide similar, though less pronounced, benefits. The crucial factor appears to be the density of vegetation and the degree to which the natural environment can block out urban noise and visual distractions. Some forward-thinking cities in countries like South Korea, Finland, and Canada have begun incorporating “healing forests” into their urban planning initiatives, recognizing the public health value of accessible natural spaces.

Medical professionals in several countries have started prescribing nature-based activities as complementary treatments for patients with stress-related conditions, mild to moderate depression, and anxiety disorders. This approach, sometimes called “green prescriptions” or “nature prescriptions,” represents a shift toward more holistic healthcare models. While forest bathing is not intended to replace conventional medical treatments for serious mental health conditions, it offers a low-cost, side-effect-free intervention that can enhance overall treatment outcomes and prevent the development of more severe psychological problems.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

1. The term “shinrin-yoku” was first introduced in:

A. South Korea in the 1970s

B. Japan in the 1980s

C. Finland in the 1990s

D. Canada in the 2000s

2. According to the passage, what prompted Japanese scientists to study forest bathing?

A. A government request to reduce healthcare costs

B. The observation of increasing mental health problems during urbanization

C. International pressure to develop alternative therapies

D. The discovery of phytoncides in forest environments

3. Dr. Qing Li’s research primarily focused on:

A. The psychological benefits of nature walks

B. The economic impact of forest tourism

C. The measurable physical changes during forest bathing

D. The history of traditional Japanese medicine

4. Which of the following best describes “biophilia”?

A. A fear of natural environments

B. A learned behavior from childhood experiences

C. An innate human connection to nature

D. A medical condition requiring treatment

5. According to the passage, forest bathing differs from other wellness practices because it:

A. Requires expensive equipment

B. Can only be done in Japan

C. Needs professional supervision

D. Is simple and accessible

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

6. Participants in Dr. Qing Li’s studies showed a reduction in cortisol levels after forest walks.

7. Forest bathing is more effective than traditional medication for treating severe depression.

8. Phytoncides are chemicals that trees release to protect themselves from harmful organisms.

9. The positive effects on natural killer cells last for exactly 30 days after forest exposure.

Questions 10-13: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Forest bathing involves using all five senses during walks in nature. Participants should observe visual details, listen to sounds, touch surfaces like (10) __, smell the forest scent, and sometimes taste safe plants. This (11) __ helps create relaxation. Even urban green spaces like (12) __ can provide benefits. Some healthcare providers now offer (13) __ as alternative treatments for stress-related conditions.

PASSAGE 2 – The Science Behind Nature Therapy: Mechanisms and Applications

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The growing body of scientific evidence supporting nature-based interventions has led to the emergence of ecotherapy as a legitimate branch of mental health treatment. While the concept of nature’s healing properties has existed in various cultural traditions for millennia, only recently have researchers begun to systematically investigate the neurobiological mechanisms underlying these therapeutic effects. Understanding how natural environments influence brain function and psychological well-being has become crucial for developing evidence-based protocols that can be integrated into mainstream healthcare systems.

Neuroimaging studies have provided remarkable insights into how exposure to natural environments affects brain activity patterns. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research conducted by Dr. Gregory Bratman at Stanford University revealed that participants who walked for 90 minutes in a natural setting showed decreased activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex – a brain region associated with rumination and repetitive negative thinking patterns commonly seen in depression. In contrast, individuals who walked in urban environments showed no such reduction. This finding suggests that nature exposure may directly interrupt the neural processes that contribute to mood disorders, offering a neurologically-informed rationale for incorporating natural environments into mental health interventions.

Further supporting this neurological perspective, studies examining brainwave patterns through electroencephalography (EEG) have demonstrated that time spent in nature promotes increased alpha wave activity, which is associated with relaxed alertness and meditative states. Simultaneously, there is a reduction in beta wave activity, which correlates with anxious thinking and mental restlessness. Dr. Yoshifumi Miyazaki from Chiba University in Japan has spent over two decades measuring these physiological markers and has established that the autonomic nervous system shifts toward parasympathetic dominance during forest exposure – essentially activating the body’s “rest and digest” mode rather than the “fight or flight” response.

Beyond neurological changes, nature therapy appears to facilitate important cognitive restoration. According to Attention Restoration Theory (ART), developed by environmental psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan, urban environments demand significant “directed attention” – the mental effort required to filter out distractions, follow rules, and navigate complex social situations. This type of attention is a finite resource that becomes depleted with continuous use, leading to mental fatigue, reduced concentration, and impaired decision-making abilities. Natural environments, however, engage “involuntary attention” through inherently fascinating elements like flowing water, rustling leaves, and wildlife movements. This allows directed attention mechanisms to rest and recover, explaining why people consistently report feeling mentally refreshed after spending time in nature.

Trong bối cảnh đó, để hiểu rõ hơn về mental health effects of social media on adults, cần nhận thấy rằng công nghệ hiện đại đã tạo ra một môi trường hoàn toàn trái ngược với thiên nhiên, làm gia tăng nhu cầu về các liệu pháp khôi phục như liệu pháp thiên nhiên.

The biopsychosocial model of health provides a comprehensive framework for understanding nature therapy’s multifaceted benefits. This model recognizes that health outcomes result from complex interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors. Natural environments influence all three domains simultaneously: biologically through physiological changes like reduced inflammation and improved immune function; psychologically through mood enhancement and stress reduction; and socially through opportunities for group activities and community building. Horticultural therapy programs, for instance, combine physical gardening activities with social interaction and the satisfaction of nurturing living plants, addressing multiple therapeutic dimensions concurrently.

Dose-response relationships – determining how much nature exposure is needed to produce meaningful health benefits – represent an active area of research. A large-scale study published in Scientific Reports analyzed data from nearly 20,000 participants in England and found a threshold effect: people who spent at least 120 minutes per week in natural environments reported significantly better health and higher psychological well-being compared to those with no nature exposure. Interestingly, it didn’t matter whether this time was accumulated in a single visit or spread across several shorter trips. However, exceeding 300 minutes per week didn’t appear to produce additional benefits, suggesting a plateau effect in the dose-response curve.

The therapeutic applications of nature-based interventions have expanded considerably beyond simple forest walks. Adventure therapy programs combine outdoor activities with psychotherapeutic principles to treat adolescents and young adults with behavioral problems, substance abuse issues, or trauma histories. These programs leverage the challenges presented by wilderness environments – such as navigation, survival skills, and physical exertion – as metaphors for life challenges and opportunities for building resilience. The removal from everyday environments, combined with the inherent consequences of decision-making in wilderness settings, creates powerful learning experiences that can catalyze personal growth and behavioral change.

Green care farms represent another innovative application, particularly prevalent in the Netherlands and Scandinavian countries. These working agricultural settings provide structured activities for individuals with mental health conditions, intellectual disabilities, or social marginalization. Participants engage in meaningful work such as animal care, crop cultivation, and food processing within supportive communities. Research indicates that green care programs improve self-esteem, social skills, and occupational functioning while reducing psychiatric symptoms. The combination of physical activity, purposeful work, natural surroundings, and social inclusion addresses multiple recovery pathways simultaneously.

Despite the compelling evidence, several challenges face the widespread implementation of nature-based mental health interventions. Accessibility remains a significant barrier, particularly for urban populations, individuals with physical disabilities, and those in lower socioeconomic groups who may lack transportation or time flexibility. Seasonal variations in weather and climate also affect feasibility, especially in regions with harsh winters or extremely hot summers. Additionally, some individuals with severe mental health conditions may experience nature environments as threatening or overwhelming rather than restorative, highlighting the need for individualized approaches and sometimes gradual exposure protocols.

Quan tâm đến strategies for improving sleep quality cũng rất quan trọng, vì giấc ngủ chất lượng và tiếp xúc với thiên nhiên có mối liên hệ tương hỗ trong việc cải thiện sức khỏe tâm thần tổng thể.

The future of nature therapy likely involves greater integration with digital technologies and precision medicine approaches. Researchers are developing smartphone applications that can guide personalized nature prescriptions based on individual symptoms, preferences, and access to green spaces. Virtual reality (VR) nature experiences are being explored as potential alternatives when physical access is limited, though studies suggest these provide diminished benefits compared to actual nature exposure. As the field matures, establishing standardized protocols, training certification programs for nature therapy practitioners, and insurance coverage for these interventions will be essential steps toward mainstream acceptance.

Cơ chế sinh học của liệu pháp thiên nhiên tác động lên não bộ và hệ thần kinh

Cơ chế sinh học của liệu pháp thiên nhiên tác động lên não bộ và hệ thần kinh

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in the passage?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

14. Traditional cultural practices have long recognized nature’s therapeutic value before modern scientific validation.

15. Urban walking provides the same neurological benefits as walking in natural environments.

16. The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for the body’s stress response.

17. Virtual reality nature experiences are equally effective as actual nature exposure for mental health.

18. Lower socioeconomic groups may face greater barriers to accessing nature-based therapies.

Questions 19-22: Matching Headings

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs B-E from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. The role of attention in mental restoration

ii. Physical barriers to nature therapy implementation

iii. Brain imaging reveals nature’s neural impact

iv. Determining optimal duration of nature exposure

v. Historical development of ecotherapy

vi. Combining agriculture with mental health treatment

vii. The comprehensive health model of nature therapy

viii. Adventure programs for troubled youth

19. Paragraph B

20. Paragraph D

21. Paragraph F

22. Paragraph H

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below using words from the box.

According to Attention Restoration Theory, urban environments require (23) __, which is a limited mental resource. Natural settings engage (24) __ instead, allowing mental recovery. Studies showed that spending at least (25) __ minutes weekly in nature improves wellbeing. Green care farms offer structured (26) __ activities in agricultural settings to support recovery.

Word Box:

A. directed attention

B. involuntary attention

C. 60

D. 120

E. 180

F. 300

G. therapeutic

H. agricultural

I. recreational

PASSAGE 3 – Theoretical Frameworks and Future Directions in Nature-Based Mental Health Interventions

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The proliferation of research into nature-based mental health interventions has necessitated the development of robust theoretical frameworks capable of explaining the multifarious mechanisms through which natural environments exert their therapeutic effects. While early investigations relied predominantly on phenomenological observations and anecdotal evidence, contemporary scholarship has evolved to encompass sophisticated interdisciplinary paradigms that integrate insights from environmental psychology, neuroscience, evolutionary biology, and public health epidemiology. This theoretical maturation is essential not merely for academic comprehension but for the practical objective of designing evidence-based interventions that can be systematically implemented, rigorously evaluated, and scaled to address the burgeoning global mental health crisis.

The Stress Reduction Theory (SRT), pioneered by Roger Ulrich in the 1980s, posits that natural environments elicit parasympathetic nervous system activity through an evolutionarily-conditioned positive affective response to certain environmental configurations. Ulrich’s psychophysiological hypothesis suggests that humans possess innate predispositions to respond positively to savannah-like landscapes characterized by moderate spatial complexity, presence of water, verdant vegetation, and absence of immediate threats. These preferences, he argues, were adaptive during human evolutionary history, as such environments signaled resource availability and safety. Empirical support for SRT derives from studies demonstrating rapid physiological recovery from stress when individuals are exposed to natural versus urban scenes, with stress reduction occurring within minutes and involving measurable decreases in sympathetic nervous system indicators such as skin conductance, muscle tension, and heart rate.

Complementing SRT, the previously mentioned Attention Restoration Theory (ART) provides a cognitive rather than affective explanation for nature’s therapeutic properties. The Kaplans’ framework introduces the concept of “soft fascination” – the effortless attention capture by natural stimuli that simultaneously engages interest while allowing reflective thought and mental restoration. This contrasts with “hard fascination” found in urban entertainment that demands complete attentional focus, leaving no capacity for recuperation. ART identifies four components necessary for restorative environments: being away (psychological or physical escape from routine demands), extent (sufficient scope to constitute a whole different world), fascination (inherently engaging elements), and compatibility (fit between environmental characteristics and individual purposes). Natural environments typically satisfy all four criteria more readily than built environments, explaining their superior restorative capacity.

More recently, integrated biophilic design theory has emerged, attempting to synthesize evolutionary, neurological, and psychological perspectives. This framework, articulated by Stephen Kellert and others, proposes that the benefits of nature exposure result from satisfying deep-seated biophilic needs through direct experience of natural phenomena (light, air, weather, plants, animals), indirect experience (natural materials, nature imagery, natural colors and forms), and experience of space and place (prospect and refuge, organized complexity, integration of parts to wholes). Biophilic design principles have been applied to healthcare facilities, offices, and educational institutions, with studies demonstrating improved patient recovery rates, enhanced cognitive performance, and reduced stress among building occupants. However, critics note that the evidentiary base for specific design elements remains somewhat equivocal, and that the theory sometimes lacks falsifiable predictions, limiting its scientific rigor.

The salutogenic model, originally developed by Aaron Antonovsky to explain health maintenance rather than disease causation, offers another valuable lens for understanding nature therapy. This approach focuses on generalized resistance resources (GRRs) – factors that facilitate effective coping with stressors and movement toward the health end of the health-ease/dis-ease continuum. Natural environments can be conceptualized as potent GRRs that strengthen sense of coherence – an individual’s perception that life is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful. Nature experiences may enhance comprehensibility by providing ordered, predictable environments; manageability through successful navigation of outdoor challenges; and meaningfulness by fostering connections to larger ecological systems and life cycles. This perspective emphasizes pathogenic versus pathogenic thinking, aligning well with contemporary positive psychology and wellness-oriented healthcare models.

Emerging research into the human microbiome has introduced yet another mechanistic pathway linking nature exposure to mental health outcomes. The “hygiene hypothesis,” initially proposed to explain rising allergy and autoimmune conditions, suggests that reduced microbial diversity in modern sanitized environments may compromise immune system regulation. Extended versions of this hypothesis, sometimes termed the “biodiversity hypothesis” or “Old Friends hypothesis,” propose that contact with environmental microorganisms – particularly those found in soil and vegetation – plays a crucial role in modulating immune function and, through gut-brain axis communication, influencing mood and behavior. Preliminary evidence indicates that individuals with greater exposure to natural environments harbor more diverse cutaneous and gastrointestinal microbiota, and that this microbial diversity correlates with reduced inflammatory markers and lower rates of anxiety and depression. While this research domain remains in its infancy, it suggests that nature therapy may exert benefits through mechanisms more fundamental than previously imagined.

Considering the complexity of modern mental health challenges, mental health apps effectiveness has become a topic of significant interest, particularly in how digital interventions might complement traditional nature-based approaches in creating accessible support systems.

Translating theoretical understanding into practical intervention design raises numerous methodological and pragmatic challenges. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) – the gold standard for medical evidence – are difficult to execute in nature therapy research due to problems with blinding (participants know whether they’re in nature or control conditions), standardization of “dosage” (natural environments vary considerably), and ecological validity (removing people from their normal contexts may alter outcomes). Consequently, much research relies on quasi-experimental designs, observational studies, and meta-analytic reviews that synthesize findings across heterogeneous studies. While these approaches have value, they typically provide lower-quality evidence than RCTs, potentially hindering acceptance by evidence-based medicine practitioners and healthcare payers.

The social determinants of health framework highlights how nature therapy access and effectiveness may vary across populations due to structural inequities. Urban planning patterns have historically resulted in “green space inequality,” with lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color having significantly less access to quality natural areas. Even when green spaces exist, concerns about safety, lack of transportation, cultural barriers, and previous negative experiences may prevent utilization. Moreover, the very concept of “therapeutic nature” may carry cultural biases, as different populations have varied relationships with and definitions of natural environments. Effective public health implementation of nature-based interventions must therefore address these socioecological factors, ensuring equitable access and culturally responsive program design.

Looking toward future developments, several promising directions merit attention. Precision nature therapy, utilizing geospatial data, individual physiological monitoring, and machine learning algorithms, may eventually enable personalized recommendations matching specific mental health needs with optimal natural environment characteristics, exposure durations, and activity types. The “Nature Pyramid,” analogous to food pyramids, has been proposed as a public health communication tool, specifying recommended frequencies and durations for different types of nature contact – from keeping houseplants (daily) to wilderness experiences (periodically). Integration with digital phenotyping – continuous monitoring of behavior through smartphones and wearables – could allow real-time detection of declining mental health and automatically trigger nature-based intervention recommendations.

Nhận thức về social media’s role in mental health awareness cũng đặt ra câu hỏi về việc liệu công nghệ số có thể được sử dụng để thúc đẩy hành vi tìm kiếm thiên nhiên thay vì thay thế hoàn toàn trải nghiệm trực tiếp.

The planetary health perspective offers a compelling argument for nature-based mental health interventions by highlighting the reciprocal relationship between ecosystem health and human wellbeing. As climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation accelerate, maintaining access to quality natural environments becomes simultaneously more critical and more challenging. “Eco-anxiety” – distress related to environmental crises – is increasingly recognized as a significant mental health concern, particularly among younger generations. Nature therapy may serve dual functions: treating current mental health symptoms while fostering environmental stewardship behaviors that help preserve natural areas for future generations. This alignment of mental health promotion with environmental conservation creates synergistic benefits that transcend individual therapy, addressing collective wellbeing and ecological sustainability concurrently.

Finally, the ethical dimensions of commodifying nature as therapy warrant critical examination. As nature-based interventions become medicalized and commercialized, there is risk of transforming our relationship with the natural world into yet another transactional interaction focused on extracting benefits rather than fostering genuine ecological connection and responsibility. Some scholars advocate for ecocentric rather than anthropocentric frameworks that recognize intrinsic value in natural systems beyond their utility for human health. This philosophical stance suggests that the ultimate goal of nature therapy should extend beyond symptom reduction to cultivating ecological consciousness – a fundamental reorientation of human identity as embedded within, rather than separate from, the natural world. Whether such transformative outcomes can be achieved through brief therapeutic interventions or require deeper cultural shifts remains an open question that will shape the trajectory of this field.

Mô hình lý thuyết các khung lý thuyết của liệu pháp thiên nhiên và ứng dụng thực tiễn

Mô hình lý thuyết các khung lý thuyết của liệu pháp thiên nhiên và ứng dụng thực tiễn

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

27. According to Stress Reduction Theory, humans respond positively to natural environments because:

A. They learned to appreciate nature through cultural education

B. Such environments signal safety and resources from evolutionary history

C. Natural settings always contain water features

D. Urban environments are inherently dangerous

28. The concept of “soft fascination” in Attention Restoration Theory refers to:

A. Temporary distraction from nature

B. Complete absorption requiring full attention

C. Effortless engagement allowing mental restoration

D. Boredom with natural surroundings

29. The salutogenic model differs from traditional medical approaches by focusing on:

A. Disease prevention through vaccination

B. Factors that maintain health rather than cause disease

C. Pharmaceutical treatments

D. Genetic predispositions to illness

30. The “biodiversity hypothesis” suggests that nature exposure improves mental health through:

A. Visual appreciation of diverse species

B. Physical exercise in varied terrain

C. Microbial diversity affecting the gut-brain axis

D. Reduced air pollution in natural areas

31. What is the main methodological challenge in conducting randomized controlled trials for nature therapy?

A. Lack of funding for research

B. Difficulty with blinding participants and standardizing nature exposure

C. Shortage of natural environments

D. Unwillingness of participants to join studies

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each theoretical framework (32-36) with the correct characteristic (A-H).

Theoretical Frameworks:

32. Stress Reduction Theory

33. Attention Restoration Theory

34. Biophilic Design Theory

35. Salutogenic Model

36. Biodiversity Hypothesis

Characteristics:

A. Focuses on strengthening sense of coherence

B. Emphasizes evolutionary preferences for certain landscapes

C. Proposes that environmental microorganisms influence mental health

D. Identifies four components of restorative environments

E. Suggests nature therapy prevents all mental illnesses

F. Applies nature principles to building design

G. Requires pharmaceutical intervention

H. Focuses exclusively on visual aesthetics

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below using NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What term describes the unequal distribution of natural areas across different socioeconomic communities?

38. What type of anxiety is related to concerns about environmental crises and climate change?

39. What type of framework recognizes the intrinsic value of nature beyond human benefits?

40. What approach uses smartphone data and algorithms to provide personalized nature therapy recommendations?

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- B

- C

- C

- D

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- FALSE

- tree bark

- mindful approach

- botanical gardens

- green prescriptions

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- YES

- NO

- NO

- NO

- YES

- iii

- i

- iv

- vi

- A (directed attention)

- B (involuntary attention)

- D (120)

- H (agricultural)

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- B

- C

- B

- B

- D

- F

- A

- C

- green space inequality

- Eco-anxiety

- Ecocentric

- Precision nature therapy

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: shinrin-yoku, first introduced

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn A, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “The origins of forest bathing can be traced back to Japan in the 1980s”. Đây là paraphrase của “first introduced”. Đáp án B chính xác.

Câu 2: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: prompted, Japanese scientists, study forest bathing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn B, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn đề cập “Medical professionals noticed a correlation between the decreasing amount of time people spent outdoors and the rising rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. This observation prompted scientists to investigate…” Đây chính xác là đáp án B về việc quan sát các vấn đề sức khỏe tâm thần tăng lên trong quá trình đô thị hóa.

Câu 3: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Dr. Qing Li, research, focused on

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Dr. Qing Li… has been at the forefront of studying the physiological effects of forest bathing. His research team has discovered that when people spend time in forests, their bodies undergo measurable positive changes.” Từ “physiological effects” và “measurable positive changes” tương ứng với đáp án C.

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: cortisol levels, reduced, forest walks

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “participants who engaged in a two-hour forest walk showed a 12.4% decrease in cortisol”. Câu hỏi và thông tin trong bài khớp hoàn toàn.

Câu 7: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: forest bathing, more effective, traditional medication, severe depression

- Giải thích: Bài đọc đề cập “forest bathing is not intended to replace conventional medical treatments for serious mental health conditions” nhưng không so sánh hiệu quả giữa liệu pháp thiên nhiên và thuốc. Không có thông tin để xác nhận hay bác bỏ.

Câu 10: tree bark

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: touch surfaces, texture

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn F, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “feel the texture of tree bark” – đây là ví dụ cụ thể về việc chạm vào bề mặt trong rừng.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: traditional cultural practices, therapeutic value, before modern scientific validation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn A, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “While the concept of nature’s healing properties has existed in various cultural traditions for millennia, only recently have researchers begun to systematically investigate…” Câu này thể hiện quan điểm rõ ràng của tác giả.

Câu 15: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: urban walking, same neurological benefits, natural environments

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn B, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: “individuals who walked in urban environments showed no such reduction” – rõ ràng mâu thuẫn với câu hỏi.

Câu 19: iii (Brain imaging reveals nature’s neural impact)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Paragraph B

- Giải thích: Đoạn B tập trung vào các nghiên cứu fMRI và EEG cho thấy ảnh hưởng của thiên nhiên lên hoạt động não bộ. Từ “neuroimaging studies” và “brain activity patterns” là bằng chứng chính.

Câu 23-26: Summary Completion

- Giải thích: Các đáp án được lấy trực tiếp từ phần giải thích Attention Restoration Theory và các nghiên cứu về thời lượng tối ưu. “Directed attention” và “involuntary attention” là hai khái niệm trung tâm, “120 minutes” là ngưỡng được nghiên cứu xác định, và “agricultural” mô tả đúng bản chất của green care farms.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Stress Reduction Theory, respond positively, why

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn B, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “humans possess innate predispositions to respond positively to savannah-like landscapes… These preferences, he argues, were adaptive during human evolutionary history, as such environments signaled resource availability and safety.” Đây chính xác là đáp án B.

Câu 30: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: biodiversity hypothesis, improves mental health, through

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn F, dòng 4-7

- Giải thích: “contact with environmental microorganisms… plays a crucial role in modulating immune function and, through gut-brain axis communication, influencing mood and behavior.” Đáp án C mô tả chính xác cơ chế này.

Câu 32-36: Matching Features

- Giải thích chi tiết:

- 32 (SRT) – B: Đoạn B nói rõ về evolutionary preferences for savannah-like landscapes

- 33 (ART) – D: Đoạn C liệt kê “four components necessary for restorative environments”

- 34 (Biophilic Design) – F: Đoạn D đề cập “applied to healthcare facilities, offices, and educational institutions”

- 35 (Salutogenic Model) – A: Đoạn E giải thích về “sense of coherence” và strengthening GRRs

- 36 (Biodiversity Hypothesis) – C: Đoạn F tập trung vào microorganisms và gut-brain axis

Câu 37: green space inequality

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Từ khóa: unequal distribution, natural areas, socioeconomic communities

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn H, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Urban planning patterns have historically resulted in ‘green space inequality'” – đây là thuật ngữ chính xác được sử dụng trong bài.

Câu 40: Precision nature therapy

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Từ khóa: smartphone data, algorithms, personalized recommendations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn I, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Precision nature therapy, utilizing geospatial data, individual physiological monitoring, and machine learning algorithms” – đây là cụm từ ba chữ chính xác.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| therapeutic | adj | /ˌθerəˈpjuːtɪk/ | có tính điều trị, chữa bệnh | exploring various therapeutic approaches | therapeutic benefits, therapeutic effects |

| shinrin-yoku | n | /ʃɪnrɪn ˈjoʊkuː/ | tắm rừng (tiếng Nhật) | practice that has gained attention is shinrin-yoku | practice shinrin-yoku |

| psychological well-being | n phrase | /ˌsaɪkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl wel ˈbiːɪŋ/ | sức khỏe tâm lý, tinh thần | improve physical and psychological well-being | enhance psychological well-being |

| lifestyle-related diseases | n phrase | /ˈlaɪfstaɪl rɪˈleɪtɪd dɪˈziːzɪz/ | các bệnh liên quan đến lối sống | various lifestyle-related diseases | prevent lifestyle-related diseases |

| cortisol | n | /ˈkɔːrtɪsɒl/ | cortisol (hormone căng thẳng) | reduction in cortisol levels | cortisol levels, stress hormone cortisol |

| cardiovascular health | n phrase | /ˌkɑːdiəʊˈvæskjələr helθ/ | sức khỏe tim mạch | improve overall cardiovascular health | promote cardiovascular health |

| biophilia | n | /ˌbaɪəʊˈfɪliə/ | xu hướng yêu thiên nhiên bẩm sinh | attribute these effects to biophilia | concept of biophilia |

| phytoncides | n | /ˈfaɪtənsaɪdz/ | hợp chất thực vật phòng vệ | involves phytoncides released by trees | breathe in phytoncides |

| immune system | n phrase | /ɪˈmjuːn ˈsɪstəm/ | hệ miễn dịch | their immune systems receive a boost | strengthen immune system |

| natural killer cells | n phrase | /ˈnætʃrəl ˈkɪlər selz/ | tế bào diệt tự nhiên (NK cells) | increases activity of natural killer cells | NK cell activity |

| accessible | adj | /əkˈsesəbl/ | dễ tiếp cận, có thể sử dụng | remarkably simple and accessible | easily accessible |

| mindful approach | n phrase | /ˈmaɪndfəl əˈprəʊtʃ/ | cách tiếp cận có ý thức | this mindful approach to nature | take a mindful approach |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecotherapy | n | /ˈiːkəʊˌθerəpi/ | liệu pháp sinh thái | emergence of ecotherapy as legitimate branch | practice ecotherapy |

| neurobiological mechanisms | n phrase | /ˌnjʊərəʊbaɪəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈmekənɪzəmz/ | cơ chế thần kinh sinh học | investigate neurobiological mechanisms | underlying neurobiological mechanisms |

| neuroimaging | n | /ˈnjʊərəʊˌɪmɪdʒɪŋ/ | chụp hình thần kinh | neuroimaging studies provided insights | neuroimaging techniques |

| subgenual prefrontal cortex | n phrase | /sʌbˈdʒenjuəl priːˈfrʌntəl ˈkɔːteks/ | vỏ não trước trán dưới gối | decreased activity in subgenual prefrontal cortex | brain region subgenual prefrontal cortex |

| rumination | n | /ˌruːmɪˈneɪʃən/ | sự trăn trở, suy nghĩ tiêu cực | associated with rumination and negative thinking | mental rumination |

| brainwave patterns | n phrase | /ˈbreɪnweɪv ˈpætərnz/ | mô hình sóng não | examining brainwave patterns through EEG | measure brainwave patterns |

| alpha wave activity | n phrase | /ˈælfə weɪv ækˈtɪvəti/ | hoạt động sóng alpha | promotes increased alpha wave activity | increased alpha wave activity |

| parasympathetic dominance | n phrase | /ˌpærəsɪmpəˈθetɪk ˈdɒmɪnəns/ | sự thống trị của hệ phó giao cảm | shifts toward parasympathetic dominance | achieve parasympathetic dominance |

| cognitive restoration | n phrase | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˌrestəˈreɪʃən/ | phục hồi nhận thức | facilitates important cognitive restoration | promote cognitive restoration |

| directed attention | n phrase | /dɪˈrektɪd əˈtenʃən/ | sự chú ý định hướng | urban environments demand directed attention | require directed attention |

| involuntary attention | n phrase | /ɪnˈvɒləntri əˈtenʃən/ | sự chú ý vô thức | engage involuntary attention | capture involuntary attention |

| biopsychosocial model | n phrase | /ˌbaɪəʊˌsaɪkəʊˈsəʊʃəl ˈmɒdəl/ | mô hình sinh tâm xã hội | biopsychosocial model of health | apply biopsychosocial model |

| horticultural therapy | n phrase | /ˌhɔːtɪˈkʌltʃərəl ˈθerəpi/ | liệu pháp làm vườn | horticultural therapy programs combine | practice horticultural therapy |

| dose-response relationships | n phrase | /dəʊs rɪˈspɒns rɪˈleɪʃənʃɪps/ | mối quan hệ liều-đáp ứng | determining dose-response relationships | establish dose-response relationships |

| plateau effect | n phrase | /plæˈtəʊ ɪˈfekt/ | hiệu ứng bình nguyên | suggesting a plateau effect | reach plateau effect |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| multifarious | adj | /ˌmʌltɪˈfeəriəs/ | đa dạng, nhiều mặt | multifarious mechanisms | multifarious benefits | |

| phenomenological | adj | /fɪˌnɒmɪnəˈlɒdʒɪkəl/ | thuộc hiện tượng luận | relied on phenomenological observations | phenomenological approach | |

| interdisciplinary paradigms | n phrase | /ˌɪntəˈdɪsəplɪnəri ˈpærədaɪmz/ | mô hình liên ngành | encompass interdisciplinary paradigms | develop interdisciplinary paradigms | |

| psychophysiological hypothesis | n phrase | /ˌsaɪkəʊˌfɪziəˈlɒdʒɪkəl haɪˈpɒθəsɪs/ | giả thuyết tâm lý sinh lý | Ulrich’s psychophysiological hypothesis | propose psychophysiological hypothesis | |

| innate predispositions | n phrase | /ɪˈneɪt ˌpriːdɪspəˈzɪʃənz/ | khuynh hướng bẩm sinh | humans possess innate predispositions | innate predispositions to nature | |

| verdant vegetation | n phrase | /ˈvɜːdənt ˌvedʒəˈteɪʃən/ | thảm thực vật xanh tươi | presence of verdant vegetation | lush verdant vegetation | |

| soft fascination | n phrase | /sɒft ˌfæsɪˈneɪʃən/ | sự hấp dẫn nhẹ nhàng | introduces concept of soft fascination | experience soft fascination | |

| reflective thought | n phrase | /rɪˈflektɪv θɔːt/ | suy nghĩ phản chiếu | allows reflective thought | engage in reflective thought | |

| biophilic design theory | n phrase | /ˌbaɪəʊˈfɪlɪk dɪˈzaɪn ˈθɪəri/ | lý thuyết thiết kế ưa sinh học | integrated biophilic design theory | apply biophilic design theory | |

| equivocal | adj | /ɪˈkwɪvəkəl/ | mơ hồ, không rõ ràng | evidentiary base remains equivocal | equivocal evidence | |

| falsifiable predictions | n phrase | /ˈfɔːlsɪfaɪəbl prɪˈdɪkʃənz/ | dự đoán có thể bác bỏ | lacks falsifiable predictions | make falsifiable predictions | |

| salutogenic model | n phrase | /ˌsæljʊtəˈdʒenɪk ˈmɒdəl/ | mô hình sinh sức khỏe | salutogenic model offers valuable lens | apply salutogenic model | |

| generalized resistance resources | n phrase | /ˈdʒenərəlaɪzd rɪˈzɪstəns rɪˈsɔːsɪz/ | nguồn lực chống chịu tổng quát | focuses on generalized resistance resources | build generalized resistance resources | |

| sense of coherence | n phrase | /sens əv kəʊˈhɪərəns/ | cảm giác mạch lạc, nhất quán | strengthen sense of coherence | enhance sense of coherence | |

| pathogenic | adj | /ˌpæθəˈdʒenɪk/ | gây bệnh | pathogenic versus salutogenic thinking | pathogenic approach | |

| gut-brain axis | n phrase | /ɡʌt breɪn ˈæksɪs/ | trục ruột-não | through gut-brain axis communication | gut-brain axis connection | |

| cutaneous microbiota | n phrase | /kjuːˈteɪniəs ˌmaɪkrəʊbaɪˈəʊtə/ | hệ vi sinh vật da | more diverse cutaneous microbiota | cutaneous microbiota diversity | |

| quasi-experimental designs | n phrase | /ˈkweɪzaɪ ɪkˌsperɪˈmentəl dɪˈzaɪnz/ | thiết kế bán thực nghiệm | research relies on quasi-experimental designs | use quasi-experimental designs | |

| ecological validity | n phrase | /ˌiːkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl vəˈlɪdəti/ | giá trị sinh thái | problems with ecological validity | ensure ecological validity | |

| socioecological factors | n phrase | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˌiːkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈfæktəz/ | các yếu tố xã hội-sinh thái | must address socioecological factors | consider socioecological factors | |

| geospatial data | n phrase | /ˌdʒiːəʊˈspeɪʃəl ˈdeɪtə/ | dữ liệu không gian địa lý | utilizing geospatial data | analyze geospatial data | |

| digital phenotyping | n phrase | /ˈdɪdʒɪtəl ˈfiːnətaɪpɪŋ/ | kiểu hình số | integration with digital phenotyping | use digital phenotyping | |

| reciprocal relationship | n phrase | /rɪˈsɪprəkəl rɪˈleɪʃənʃɪp/ | mối quan hệ tương hỗ | highlighting reciprocal relationship | establish reciprocal relationship | |

| eco-anxiety | n | /ˈiːkəʊ æŋˈzaɪəti/ | lo âu sinh thái | eco-anxiety is increasingly recognized | experience eco-anxiety | |

| environmental stewardship | n phrase | /ɪnˌvaɪrənˈmentəl ˈstjuːədʃɪp/ | quản lý môi trường | fostering environmental stewardship behaviors | practice environmental stewardship | |

| synergistic benefits | n phrase | /ˌsɪnəˈdʒɪstɪk ˈbenɪfɪts/ | lợi ích cộng hưởng | creates synergistic benefits | achieve synergistic benefits | |

| ecocentric | adj | /ˌiːkəʊˈsentrɪk/ | lấy sinh thái làm trung tâm | advocate for ecocentric frameworks | ecocentric perspective | |

| anthropocentric | adj | /ˌænθrəpəˈsentrɪk/ | lấy con người làm trung tâm | rather than anthropocentric frameworks | anthropocentric worldview | |

| ecological consciousness | n phrase | /ˌiːkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈkɒnʃəsnəs/ | ý thức sinh thái | cultivating ecological consciousness | develop ecological consciousness |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề về liệu pháp thiên nhiên và sức khỏe tâm thần không chỉ phản ánh xu hướng toàn cầu trong nghiên cứu y học mà còn là một trong những đề tài thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS Reading Test. Bộ đề thi mẫu này đã cung cấp cho bạn trải nghiệm hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages có độ khó tăng dần từ Easy (Band 5.0-6.5) đến Medium (Band 6.0-7.5) và Hard (Band 7.0-9.0), bao gồm tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như kỳ thi thật.

Qua việc thực hành với đề thi này, bạn đã được làm quen với 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading: Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Yes/No/Not Given, Matching Headings, Matching Information, Summary Completion, Matching Features và Short-answer Questions. Mỗi dạng câu hỏi yêu cầu kỹ năng đọc và chiến lược làm bài khác nhau, từ scanning nhanh để tìm thông tin cụ thể đến reading for detail để hiểu sâu các ý chính.

Phần đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích đã chỉ ra cách paraphrase giữa câu hỏi và passage, vị trí chính xác của thông tin trong bài đọc, và lý do tại sao mỗi đáp án là đúng. Đây là yếu tố then chốt giúp bạn không chỉ biết đáp án là gì mà còn hiểu tại sao – một kỹ năng quan trọng để tự cải thiện band điểm Reading.

Bộ từ vựng được tổng hợp theo từng passage cung cấp cho bạn những collocations và academic words thường gặp trong các bài thi IELTS Reading thực tế. Việc học từ vựng trong ngữ cảnh như thế này sẽ giúp bạn ghi nhớ lâu hơn và áp dụng hiệu quả hơn trong cả bài thi Writing và Speaking.

Hãy nhớ rằng, để đạt band điểm cao trong IELTS Reading, bạn cần thực hành thường xuyên với các đề thi có độ khó tương đương thi thật, quản lý thời gian chặt chẽ (60 phút cho 40 câu hỏi), và phát triển kỹ năng đọc lướt (skimming) cũng như đọc chi tiết (scanning). Đề thi này là một công cụ tuyệt vời để bạn tự đánh giá trình độ hiện tại và xác định những điểm cần cải thiện trên con đường chinh phục IELTS.

Chúc bạn luyện tập hiệu quả và đạt được band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!

[…] hệ giữa tiếp xúc với thiên nhiên và sức khỏe tinh thần, các nghiên cứu về how to promote mental health through nature therapy đã chỉ ra những tác động tích cực tương tự khi trẻ em tham gia các hoạt […]