Chủ đề về tự động hóa trong sản xuất và những tác động xã hội của nó đang ngày càng trở nên phổ biến trong các đề thi IELTS Reading gần đây. Đây là một chủ đề quan trọng phản ánh xu hướng phát triển công nghệ toàn cầu, xuất hiện thường xuyên ở cả ba passages với nhiều góc độ khác nhau: từ lịch sử phát triển, tác động kinh tế cho đến những thách thức xã hội.

Bài viết này cung cấp một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần, giúp bạn:

- Làm quen với đề thi thật gồm 3 passages (Easy → Medium → Hard) với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi

- Thực hành đa dạng các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading

- Kiểm tra đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí và cách paraphrase

- Học từ vựng chuyên ngành quan trọng và rèn luyện kỹ thuật làm bài hiệu quả

- Nâng cao khả năng đọc hiểu từ band 5.0 lên 7.5+

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, đặc biệt hữu ích cho những ai đang nhắm đến band điểm 7.0+ và muốn làm quen với chủ đề công nghệ – xã hội trong IELTS.

Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

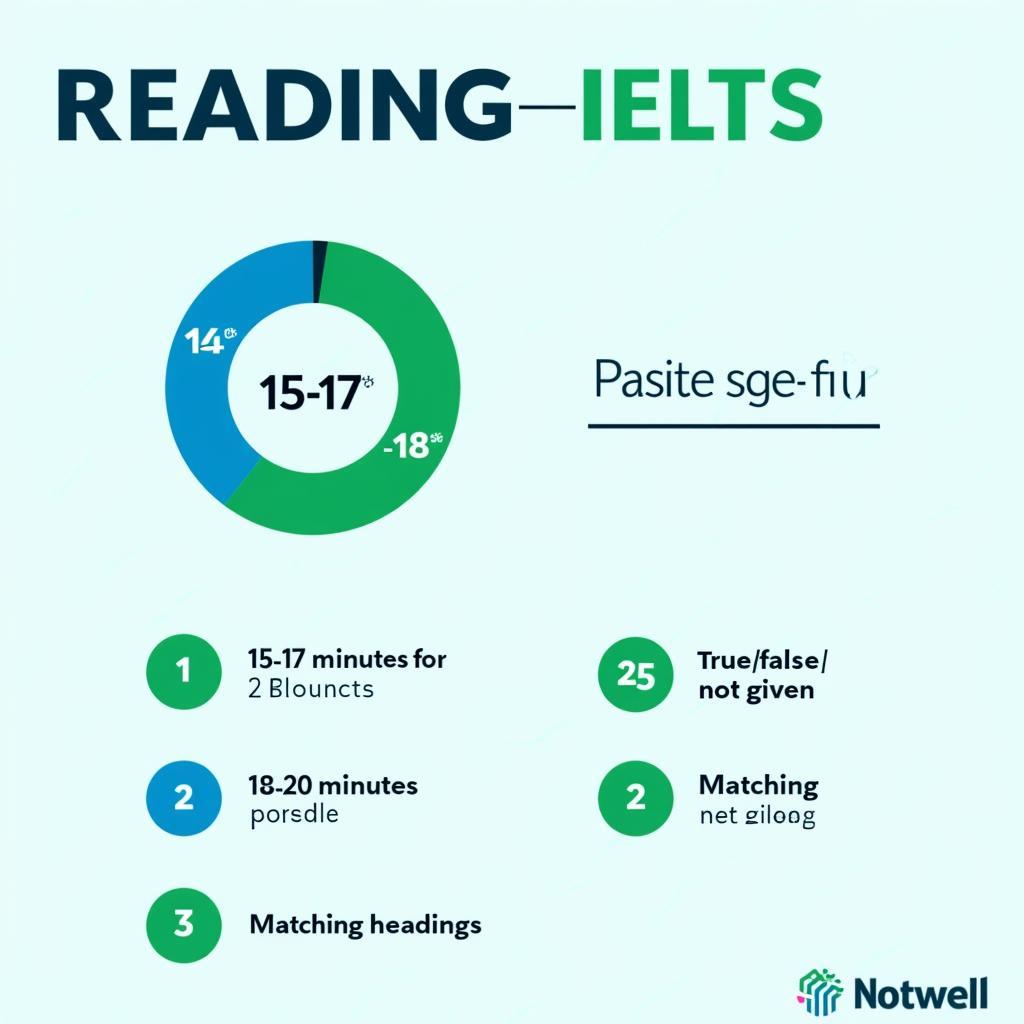

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Điểm số của bạn được tính dựa trên số câu trả lời đúng, không bị trừ điểm khi sai.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (câu hỏi 1-13) – Độ khó thấp nhất

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (câu hỏi 14-26) – Độ khó trung bình

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (câu hỏi 27-40) – Độ khó cao nhất

Lưu ý dành 2-3 phút cuối để chuyển đáp án vào Answer Sheet. Không có thêm thời gian sau khi hết 60 phút.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất:

- Multiple Choice – Trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không có

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu

- Matching Features – Nối đặc điểm với thông tin

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

Mỗi dạng câu hỏi yêu cầu kỹ năng đọc hiểu khác nhau, từ tìm thông tin chi tiết đến hiểu ý chính và suy luận.

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Dawn of Automation in Manufacturing

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The history of automation in manufacturing can be traced back to the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century, when water and steam power began to replace human and animal labor. However, the modern concept of automation truly emerged in the mid-20th century with the development of programmable machines and computer-controlled systems. Today, automation has become an integral part of manufacturing processes worldwide, fundamentally transforming how goods are produced and delivered to consumers.

Automation refers to the use of technology to perform tasks with minimal human intervention. In manufacturing contexts, this can range from simple mechanical devices that repeat basic movements to sophisticated robotic systems equipped with artificial intelligence that can make decisions and adapt to changing conditions. The primary advantage of automation is its ability to increase productivity while reducing costs. Machines can operate continuously without breaks, maintain consistent quality standards, and perform tasks that would be dangerous or impossible for human workers.

The automotive industry was among the first to embrace automation on a large scale. In the 1960s and 1970s, car manufacturers began installing robotic arms on assembly lines to perform repetitive tasks such as welding, painting, and parts installation. These early robots were relatively simple, following pre-programmed sequences without the ability to respond to unexpected situations. Nevertheless, they proved highly effective at improving production speed and reducing workplace injuries caused by repetitive strain or exposure to hazardous materials.

As technology advanced, automation systems became increasingly sophisticated. The introduction of sensors and feedback mechanisms allowed machines to monitor their own performance and make adjustments in real-time. Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines revolutionized precision manufacturing, enabling the production of complex components with tolerances measured in micrometers. By the 1990s, many factories had implemented integrated automation systems where multiple machines communicated with each other, coordinating their activities to optimize the entire production process.

The benefits of automation extend beyond the factory floor. Supply chain management has been transformed by automated inventory tracking systems, which use barcode scanners and radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags to monitor products from raw materials to final delivery. Warehouse operations have been revolutionized by automated guided vehicles (AGVs) and robotic picking systems that can locate and retrieve items far more quickly than human workers. These innovations have enabled the rapid delivery times that consumers have come to expect in the age of e-commerce.

Today’s most advanced manufacturing facilities are sometimes referred to as “lights-out factories” because they can operate in complete darkness with minimal human presence. These facilities utilize collaborative robots, or “cobots,” designed to work safely alongside human workers when necessary. Unlike traditional industrial robots that must be caged off for safety reasons, cobots are equipped with sensors that detect human presence and can immediately stop or slow their movements to prevent accidents.

Despite these impressive technological achievements, the introduction of automation has raised important questions about the future of work. While automation creates new jobs in fields such as robot maintenance, programming, and systems integration, it simultaneously eliminates many traditional manufacturing positions. This shift has particularly affected workers with limited education or specialized skills, who may find it difficult to transition to the new roles created by automation. Understanding both the benefits and challenges of automation is essential as society continues to navigate this technological transformation.

Lịch sử phát triển tự động hóa trong sản xuất công nghiệp từ cách mạng công nghiệp đến hiện đại

Lịch sử phát triển tự động hóa trong sản xuất công nghiệp từ cách mạng công nghiệp đến hiện đại

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

Modern automation began during the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century.

-

Automated machines can maintain more consistent quality than human workers.

-

The automotive industry was the last manufacturing sector to adopt automation.

-

Early industrial robots in the 1960s could adapt to unexpected situations.

-

Collaborative robots must be separated from human workers by safety barriers.

Questions 6-9

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

Computer Numerical Control machines made it possible to produce items with extremely high _____.

-

Modern warehouses use _____ to track and locate products efficiently.

-

Factories that can operate with almost no human workers present are called _____.

-

Automation has created new employment opportunities in areas like robot maintenance and _____.

Questions 10-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

- According to the passage, what is the main advantage of automation in manufacturing?

- A. It reduces the need for skilled workers

- B. It increases productivity while lowering costs

- C. It eliminates all workplace accidents

- D. It improves product design

- What enabled machines to adjust their performance automatically?

- A. Robotic arms

- B. Pre-programmed sequences

- C. Sensors and feedback mechanisms

- D. Computer programmers

- How have supply chains been improved by automation?

- A. Through faster product design

- B. By reducing the cost of raw materials

- C. Via automated tracking and monitoring systems

- D. Through increased human supervision

- What challenge does automation create for some workers?

- A. Difficulty in transitioning to new roles

- B. Increased working hours

- C. Exposure to hazardous materials

- D. Need to work in darkness

PASSAGE 2 – Economic and Social Shifts in the Age of Automation

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The proliferation of automation in manufacturing has triggered a profound economic restructuring that extends far beyond the factory floor, reshaping labor markets, wage structures, and the very nature of work itself. While proponents of automation emphasize its potential to enhance competitiveness, boost economic growth, and create entirely new industries, critics point to widening inequality, job displacement, and the erosion of middle-class employment as inevitable consequences of this technological shift. Understanding these multifaceted impacts requires examining both the macro-economic trends and the lived experiences of workers and communities affected by automation.

Historically, technological advancement has been a double-edged sword for workers. The mechanization of agriculture in the early 20th century displaced millions of farm laborers, yet simultaneously created opportunities in urban manufacturing centers. Similarly, the current wave of automation is eliminating certain categories of employment while generating demand for new skills and expertise. However, the pace and scale of contemporary automation may be unprecedented. A 2019 study by the Oxford Martin School estimated that up to 47% of jobs in developed economies could be susceptible to automation within the next two decades, with routine manual tasks and even some cognitive functions now performed by algorithmic systems and machine learning applications.

The distributional effects of automation have become increasingly apparent. Manufacturing employment in advanced economies has declined substantially over recent decades, even as industrial output has continued to rise—a phenomenon economists call “jobless growth.” In the United States, manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at approximately 19.5 million jobs and has since fallen to around 12.8 million, despite the economy nearly tripling in size. While some of this decline results from offshoring and global trade dynamics, research suggests that automation accounts for a significant proportion of job losses, particularly in middle-skill positions that once provided pathways to economic security for workers without advanced education.

The impact of automation varies considerably across different demographic groups and geographic regions. Older workers often face particular challenges, as they may have spent decades developing expertise in techniques that suddenly become obsolete. Retraining programs, while well-intentioned, frequently fail to provide adequate preparation for the demands of emerging occupations. Geographic concentration of manufacturing also means that automation’s effects are unevenly distributed; communities that historically relied on factory employment may experience cascading economic decline when plants close or dramatically reduce their workforce. This pattern has contributed to growing regional inequality and social polarization in many countries.

Yet the narrative of automation as purely job-destroying technology overlooks important countervailing forces. Automation can make companies more competitive, potentially preserving employment that might otherwise be lost to international competition. Lower production costs may translate into reduced prices for consumers, increasing purchasing power and stimulating demand across the economy. Furthermore, automation typically augments rather than completely replaces human labor in many contexts. For instance, while computer-aided design (CAD) software has transformed architecture and engineering, these tools have enhanced rather than eliminated the need for skilled professionals who can operate them creatively and strategically.

The emergence of collaborative automation, where humans and machines work in complementary roles, represents a promising model for the future. In this paradigm, automation handles physically demanding, repetitive, or precision-critical tasks, while human workers focus on activities requiring judgment, creativity, interpersonal skills, and adaptability—qualities that remain difficult to automate. Some manufacturers have found that this approach yields better results than attempting to fully automate production, as it combines the strengths of both human and machine capabilities.

Policy responses to automation’s social implications vary widely across different national contexts. Scandinavian countries have invested heavily in “active labor market policies” that emphasize continuous education, skills development, and strong social safety nets to help workers navigate transitions. Germany’s “Industry 4.0” initiative seeks to position the country as a leader in smart manufacturing while also addressing workforce implications through apprenticeship programs and labor-management cooperation. In contrast, countries with more laissez-faire economic policies have generally taken a less interventionist approach, relying primarily on market mechanisms to address labor market adjustments.

The fundamental question facing policymakers is not whether to embrace automation—technological change is largely inevitable—but rather how to ensure that its benefits are broadly shared while mitigating negative externalities. This challenge requires coordinated action across multiple domains: education systems must evolve to emphasize adaptable skill sets; social protection mechanisms may need to be redesigned for an era of more fluid employment relationships; and regional development strategies should promote economic diversification to reduce vulnerability to sector-specific disruptions. The choices made in addressing these challenges will largely determine whether automation ultimately serves as a force for broadly shared prosperity or deepening social division.

Tác động kinh tế xã hội của tự động hóa đến thị trường lao động và cơ cấu việc làm

Tác động kinh tế xã hội của tự động hóa đến thị trường lao động và cơ cấu việc làm

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

- According to the passage, what percentage of jobs in developed economies might be affected by automation?

- A. 19.5%

- B. 47%

- C. 50%

- D. 79%

- The term “jobless growth” refers to:

- A. Economic expansion without corresponding employment increases

- B. Growth in the unemployment rate

- C. Expansion of part-time positions

- D. Development of the service sector

- Which factor does NOT contribute to manufacturing job losses according to the passage?

- A. Automation

- B. Offshoring

- C. Global trade

- D. Population decline

- What does the passage suggest about retraining programs?

- A. They are always successful

- B. They often inadequately prepare workers

- C. They are too expensive

- D. They focus on the wrong skills

- According to the passage, collaborative automation involves:

- A. Robots working together

- B. Different companies cooperating

- C. Humans and machines in complementary roles

- D. Government and industry partnerships

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

The effects of automation are not uniform across society. 19. __ often struggle because their skills become outdated, while 20. __ that depend heavily on manufacturing may experience serious economic problems. However, automation is not purely negative. It can help companies remain 21. __ in global markets and may actually 22. __ human labor rather than replace it entirely. The approach called 23. __ combines human strengths like creativity with machine precision and efficiency.

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Scandinavian countries have implemented comprehensive policies to help workers adjust to automation.

-

The German Industry 4.0 initiative has been completely unsuccessful.

-

All countries should adopt identical policies to address automation’s impacts.

PASSAGE 3 – Reimagining Social Contracts in an Automated Economy

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The inexorable advance of automation in manufacturing represents not merely a technological transition but a fundamental challenge to the social contracts and institutional frameworks that have governed industrial societies since the mid-20th century. The post-war Fordist model—characterized by mass production, stable employment, progressive wage growth, and comprehensive social welfare systems funded by expanding tax bases—rested on assumptions about the relationship between productivity, employment, and prosperity that are increasingly untenable in an era of sophisticated automation. As machine intelligence and robotic systems assume roles previously reserved for human workers, societies face profound questions about the organization of work, the distribution of economic gains, and the very foundations of human dignity and social participation.

The philosophical dimensions of this transformation extend beyond utilitarian calculations of employment figures and GDP growth. Work has historically served multiple functions in human society: providing not only material sustenance but also social identity, communal belonging, a sense of purpose, and structured time. The Protestant work ethic, which emerged alongside industrial capitalism, sacralized labor as the primary means through which individuals demonstrated their worth and contributed to collective welfare. This ideological framework has profoundly shaped modern welfare states, which typically condition social benefits on employment status or the willingness to seek work. When automation decouples productivity from employment, these longstanding assumptions require fundamental reconsideration.

Economist John Maynard Keynes presciently anticipated some of these challenges in his 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” in which he predicted that technological progress would eventually create a society of abundance where humanity’s primary problem would be how to use leisure time rather than how to secure basic necessities. However, Keynes assumed that the benefits of productivity gains would be equitably distributed, perhaps through shortened working hours that would spread available employment across the population. Contemporary reality has diverged markedly from this vision. Rather than shared leisure, we observe bifurcated labor markets where some workers face chronic unemployment or precarious employment while others experience intensified work demands and extended hours. The gains from automation have disproportionately accrued to capital owners and those possessing specialized technical skills, exacerbating wealth inequality to levels not seen since the Gilded Age.

This distributive failure has catalyzed renewed interest in heterodox economic proposals aimed at ensuring that automation’s benefits reach broader populations. Universal Basic Income (UBI)—a policy whereby all citizens receive unconditional cash payments from the government—has garnered support from both libertarian and progressive camps, albeit for different reasons. Proponents argue that UBI would provide economic security in an era of employment volatility, eliminate the bureaucratic complexity of means-tested welfare programs, and preserve individual autonomy by allowing people to choose how to spend their resources. Critics, however, contend that UBI might reduce labor force participation, prove fiscally unsustainable at meaningful payment levels, and potentially erode the social and psychological benefits associated with employment. Pilot programs in Finland, Kenya, and parts of the United States have yielded mixed results, with studies showing improved subjective well-being but limited impact on employment behavior—though interpreting these findings remains contentious due to methodological limitations and the non-universal nature of the experiments.

Alternative approaches focus on restructuring work rather than delinking income from employment. Job guarantee programs, which promise government employment to all who seek it, represent one such strategy. Proponents, including economist Pavlina Tcherneva, argue that job guarantees would serve as an automatic stabilizer during economic downturns, provide socially useful labor for community needs that markets fail to address, and preserve the social benefits of employment. Skeptics question whether government can effectively manage large-scale employment programs and worry about potential distortions in private labor markets. Another proposed intervention involves mandating reduced working hours through mechanisms such as a four-day work week, thereby redistributing available employment while potentially improving work-life balance and employee well-being—though concerns about income adequacy and implementation challenges persist.

The educational implications of widespread automation are equally profound and contested. If algorithmic systems can perform not only routine manual tasks but also increasingly complex analytical functions—diagnosing diseases, writing legal briefs, analyzing financial data—what capabilities should education systems cultivate? Some analysts emphasize “uniquely human skills” such as creativity, emotional intelligence, ethical reasoning, and complex communication that remain resistant to automation. Others question whether these qualities can be systematically taught or whether credentialing systems will simply create new forms of exclusion. The concept of “lifelong learning” has become ubiquitous in policy discourse, yet implementation faces substantial obstacles: opportunity costs for workers who must support themselves while retraining, uncertain returns on educational investments given rapid technological change, and potential age discrimination against older workers seeking to acquire new skills.

Beyond economic and educational reforms, automation raises existential questions about the future trajectory of human societies. Techno-optimists envision a post-scarcity world where automation liberates humanity from drudgery, enabling pursuits of artistic creation, scientific inquiry, community service, and personal development. Skeptics warn of dystopian scenarios involving permanent underclasses, social fragmentation, and the concentration of power among those who control automated production systems. Reality will likely involve contested political struggles over how to govern these technologies and distribute their fruits. The labor movements that secured workers’ rights and social protections during earlier phases of industrialization emerged through decades of organizing and conflict; analogous movements may be necessary to ensure that automation serves collective human flourishing rather than narrow interests.

Ultimately, the question facing contemporary societies is not whether to embrace automation but rather what kind of society to build as automation advances. This requires normative judgments about the purpose of economic activity, the obligations societies owe their members, and the relative weight assigned to efficiency, equity, autonomy, and community. Technical trajectories are not predetermined; they reflect choices made by engineers, executives, investors, policymakers, and citizens. Democratic deliberation about automation’s direction and governance remains essential if these powerful technologies are to serve broadly defined human welfare rather than simply optimizing narrow metrics of productivity and profit. The social implications of automation ultimately depend less on the capabilities of machines than on the values and institutions humans construct to guide their deployment.

Các giải pháp chính sách xã hội ứng phó với tự động hóa trong sản xuất và kinh tế

Các giải pháp chính sách xã hội ứng phó với tự động hóa trong sản xuất và kinh tế

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

- According to the passage, the Fordist model was based on:

- A. Temporary employment and flexible wages

- B. Mass production and stable employment

- C. Individual entrepreneurship

- D. Agricultural production

- What did John Maynard Keynes predict in his 1930 essay?

- A. Automation would cause permanent unemployment

- B. Technology would eventually create abundance and leisure

- C. Work hours would increase dramatically

- D. Capitalism would collapse

- The passage suggests that automation’s benefits have primarily gone to:

- A. All workers equally

- B. Government programs

- C. Capital owners and those with technical skills

- D. Unemployed workers

- According to the passage, critics of Universal Basic Income argue that it might:

- A. Increase employment too much

- B. Be too simple to administer

- C. Reduce labor force participation

- D. Eliminate all social problems

- What do techno-optimists believe about automation’s future?

- A. It will lead to dystopian scenarios

- B. It will liberate humans from tedious work

- C. It will cause permanent unemployment

- D. It will reduce scientific inquiry

Questions 32-36

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Work has historically provided more than just income—it offers 32. __, a sense of purpose, and community connection. The 33. __ __ __, which developed with industrial capitalism, made labor central to how people proved their value. Modern welfare systems often link benefits to employment, but when automation separates productivity from jobs, these assumptions must be reconsidered. Contemporary labor markets have become 34. __, with some facing unemployment while others work excessive hours. Proposals like 35. __ __ __ aim to ensure automation’s benefits reach everyone, though critics worry about effects on work participation and 36. __ __.

Questions 37-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Pilot programs testing Universal Basic Income have produced conclusive evidence about its effectiveness.

-

Job guarantee programs would provide employment to anyone seeking work through government initiatives.

-

Educational systems universally agree on what skills should be taught in an automated economy.

-

The social impacts of automation depend more on human choices and institutions than on technology itself.

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- precision (manufacturing)

- RFID tags / radio-frequency identification

- lights-out factories

- systems integration

- B

- C

- C

- A

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- B

- A

- D

- B

- C

- Older workers

- Geographic regions / Communities

- competitive

- augments

- collaborative automation

- YES

- NO

- NOT GIVEN

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- B

- C

- C

- B

- social identity

- Protestant work ethic

- bifurcated

- Universal Basic Income

- fiscal sustainability / labor force

- NO

- YES

- NO

- YES

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: modern automation, Industrial Revolution, 18th century

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Câu hỏi nói “Modern automation began during the Industrial Revolution” nhưng bài đọc nói rõ “The history of automation…can be traced back to the Industrial Revolution” NHƯNG “the modern concept of automation truly emerged in the mid-20th century”. Đây là paraphrase quan trọng – lịch sử có thể bắt nguồn từ thế kỷ 18 nhưng khái niệm hiện đại mới xuất hiện thế kỷ 20. Do đó câu này FALSE.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: maintain consistent quality, human workers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Machines can…maintain consistent quality standards” – khớp hoàn toàn với câu hỏi “maintain more consistent quality than human workers”. Đây là thông tin rõ ràng được nêu trong bài.

Câu 5: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: collaborative robots, separated, safety barriers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “Unlike traditional industrial robots that must be caged off for safety reasons, cobots are equipped with sensors…” – nghĩa là cobots KHÔNG cần được ngăn cách. Câu hỏi nói chúng “must be separated” nên đây là FALSE.

Câu 8: lights-out factories

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: operate, almost no human workers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “lights-out factories because they can operate in complete darkness with minimal human presence” – paraphrase của “almost no human workers present” là “minimal human presence”.

Câu 10: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main advantage, automation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: Bài nói “The primary advantage of automation is its ability to increase productivity while reducing costs” – khớp chính xác với đáp án B. Các đáp án khác không được nêu là “main advantage”.

Câu 13: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: challenge, automation creates, workers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “workers…may find it difficult to transition to the new roles” – paraphrase thành “Difficulty in transitioning to new roles” ở đáp án A.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: percentage, jobs, developed economies, automation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu rõ “A 2019 study by the Oxford Martin School estimated that up to 47% of jobs in developed economies could be susceptible to automation”. Con số 47% là đáp án chính xác.

Câu 15: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: jobless growth, refers to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài giải thích “industrial output has continued to rise” nhưng “manufacturing employment…has declined substantially”—hiện tượng này được gọi là “jobless growth”. Đây là tăng trưởng kinh tế không kèm tăng việc làm, khớp với đáp án A.

Câu 17: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: retraining programs

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Retraining programs, while well-intentioned, frequently fail to provide adequate preparation” – paraphrase thành “often inadequately prepare workers” ở đáp án B.

Câu 19-23: Summary Completion

- 19. Older workers – Đoạn 4, dòng 2: “Older workers often face particular challenges”

- 20. Geographic regions/Communities – Đoạn 4, dòng 5-6: “communities that historically relied on factory employment”

- 21. competitive – Đoạn 5, dòng 2: “Automation can make companies more competitive”

- 22. augments – Đoạn 5, dòng 5: “automation typically augments rather than completely replaces human labor”

- 23. collaborative automation – Đoạn 6, dòng 1: “The emergence of collaborative automation”

Câu 24: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Scandinavian countries have invested heavily in ‘active labor market policies’…and strong social safety nets” – đây là “comprehensive policies” nên đáp án là YES.

Câu 25: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài chỉ nói Germany’s Industry 4.0 “seeks to position the country as a leader” và “addressing workforce implications” – không có thông tin nào về việc “completely unsuccessful”, vậy câu này là NO vì mâu thuẫn với nội dung.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Fordist model, based on

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài mô tả Fordist model là “characterized by mass production, stable employment, progressive wage growth” – khớp với đáp án B.

Câu 28: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Keynes, 1930 essay, predict

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-4

- Giải thích: Bài nói Keynes “predicted that technological progress would eventually create a society of abundance where humanity’s primary problem would be how to use leisure time” – tức là công nghệ tạo ra sự dồi dào và thời gian rảnh rỗi (đáp án B).

Câu 30: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: critics, Universal Basic Income, argue

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: Bài viết “Critics…contend that UBI might reduce labor force participation” – khớp chính xác với đáp án C.

Câu 32-36: Summary Completion

- 32. social identity – Đoạn 2, dòng 2: “providing…social identity”

- 33. Protestant work ethic – Đoạn 2, dòng 4: “The Protestant work ethic”

- 34. bifurcated – Đoạn 3, dòng 8: “we observe bifurcated labor markets”

- 35. Universal Basic Income – Đoạn 4, dòng 1: “Universal Basic Income (UBI)”

- 36. fiscal sustainability – Đoạn 4, dòng 7: “prove fiscally unsustainable”

Câu 37: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 10-12

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Pilot programs…have yielded mixed results” và “interpreting these findings remains contentious due to methodological limitations” – nghĩa là CHƯA có kết luận rõ ràng, không phải “conclusive evidence”. Đáp án là NO.

Câu 40: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: Câu cuối bài nói “The social implications of automation ultimately depend less on the capabilities of machines than on the values and institutions humans construct” – hoàn toàn khớp với ý kiến trong câu hỏi. Đáp án YES.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| automation | n | /ˌɔːtəˈmeɪʃn/ | Tự động hóa | automation in manufacturing | industrial automation, factory automation |

| integral | adj | /ˈɪntɪɡrəl/ | Không thể thiếu, quan trọng | an integral part of manufacturing | integral component, play an integral role |

| embrace | v | /ɪmˈbreɪs/ | Đón nhận, chấp nhận | embrace automation | embrace change, embrace technology |

| sophisticated | adj | /səˈfɪstɪkeɪtɪd/ | Tinh vi, phức tạp | sophisticated robotic systems | sophisticated technology, sophisticated approach |

| feedback mechanism | n phrase | /ˈfiːdbæk ˈmekənɪzəm/ | Cơ chế phản hồi | sensors and feedback mechanisms | implement feedback mechanisms |

| precision | n | /prɪˈsɪʒn/ | Độ chính xác | precision manufacturing | high precision, surgical precision |

| tolerance | n | /ˈtɒlərəns/ | Dung sai (kỹ thuật) | tolerances measured in micrometers | tight tolerances, manufacturing tolerances |

| supply chain | n phrase | /səˈplaɪ tʃeɪn/ | Chuỗi cung ứng | supply chain management | global supply chain, supply chain optimization |

| collaborative robot | n phrase | /kəˈlæbərətɪv ˈrəʊbɒt/ | Robot cộng tác | collaborative robots or cobots | deploy collaborative robots |

| transformation | n | /ˌtrænsfəˈmeɪʃn/ | Sự chuyển đổi, biến đổi | technological transformation | digital transformation, undergo transformation |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proliferation | n | /prəˌlɪfəˈreɪʃn/ | Sự gia tăng nhanh chóng | proliferation of automation | nuclear proliferation, rapid proliferation |

| displacement | n | /dɪsˈpleɪsmənt/ | Sự thay thế, đẩy ra ngoài | job displacement | workforce displacement, cause displacement |

| erosion | n | /ɪˈrəʊʒn/ | Sự xói mòn | erosion of middle-class employment | soil erosion, gradual erosion |

| susceptible | adj | /səˈseptəbl/ | Dễ bị ảnh hưởng | susceptible to automation | susceptible to disease, highly susceptible |

| distributional | adj | /ˌdɪstrɪˈbjuːʃənl/ | Liên quan đến phân phối | distributional effects | distributional impact, distributional consequences |

| offshoring | n | /ˈɒfʃɔːrɪŋ/ | Chuyển sản xuất ra nước ngoài | offshoring and global trade | prevent offshoring, offshoring jobs |

| augment | v | /ɔːɡˈment/ | Tăng cường, bổ sung | augments rather than replaces | augment income, augment capabilities |

| countervailing | adj | /ˌkaʊntəˈveɪlɪŋ/ | Đối trọng, bù đắp | countervailing forces | countervailing power, countervailing effects |

| polarization | n | /ˌpəʊləraɪˈzeɪʃn/ | Sự phân cực | social polarization | political polarization, income polarization |

| laissez-faire | adj | /ˌleseɪ ˈfeə(r)/ | Tự do thị trường | laissez-faire economic policies | laissez-faire approach, laissez-faire capitalism |

| externality | n | /ˌekstɜːˈnæləti/ | Tác động bên ngoài | negative externalities | environmental externalities, address externalities |

| diversification | n | /daɪˌvɜːsɪfɪˈkeɪʃn/ | Sự đa dạng hóa | economic diversification | portfolio diversification, promote diversification |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inexorable | adj | /ɪnˈeksərəbl/ | Không thể ngăn cản | inexorable advance of automation | inexorable decline, inexorable logic |

| untenable | adj | /ʌnˈtenəbl/ | Không thể duy trì | assumptions are increasingly untenable | untenable position, become untenable |

| utilitarian | adj | /ˌjuːtɪlɪˈteəriən/ | Công lợi (triết học) | utilitarian calculations | utilitarian approach, utilitarian ethics |

| sacralize | v | /ˈseɪkrəlaɪz/ | Thần thánh hóa | sacralized labor | sacralize work, sacralize tradition |

| presciently | adv | /ˈpresiəntli/ | Một cách tiên kiến | presciently anticipated | predict presciently |

| bifurcated | adj | /ˈbaɪfəkeɪtɪd/ | Phân chia hai nhánh | bifurcated labor markets | bifurcated system, bifurcated structure |

| accrue | v | /əˈkruː/ | Tích lũy, thu được | gains have accrued to capital owners | accrue benefits, accrue interest |

| heterodox | adj | /ˈhetərədɒks/ | Không chính thống | heterodox economic proposals | heterodox approach, heterodox theory |

| contentious | adj | /kənˈtenʃəs/ | Gây tranh cãi | interpreting findings remains contentious | contentious issue, highly contentious |

| dystopian | adj | /dɪsˈtəʊpiən/ | Thuộc về xã hội phản địa đàng | dystopian scenarios | dystopian future, dystopian vision |

| deliberation | n | /dɪˌlɪbəˈreɪʃn/ | Sự thảo luận cân nhắc | democratic deliberation | careful deliberation, public deliberation |

| normative | adj | /ˈnɔːmətɪv/ | Thuộc về chuẩn mực | normative judgments | normative framework, normative principles |

| trajectory | n | /trəˈdʒektəri/ | Quỹ đạo phát triển | future trajectory of societies | career trajectory, development trajectory |

| drudgery | n | /ˈdrʌdʒəri/ | Công việc nặng nhọc, tẻ nhạt | liberate humanity from drudgery | daily drudgery, escape drudgery |

| precarious | adj | /prɪˈkeəriəs/ | Bấp bênh, không ổn định | precarious employment | precarious situation, precarious position |

Kết Luận

Chủ đề về tác động xã hội của tự động hóa trong sản xuất là một chủ đề cực kỳ quan trọng và phổ biến trong IELTS Reading, xuất hiện thường xuyên trong các đề thi gần đây. Đề thi mẫu này đã cung cấp cho bạn một trải nghiệm hoàn chỉnh với:

Ba passages đa dạng độ khó: Từ giới thiệu cơ bản về lịch sử tự động hóa (Passage 1 – Easy), qua phân tích tác động kinh tế-xã hội (Passage 2 – Medium), đến những suy ngẫm triết học về hợp đồng xã hội và tương lai (Passage 3 – Hard). Cấu trúc này phản ánh đúng format của bài thi IELTS Reading thực tế.

40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng khác nhau: Bạn đã được luyện tập đầy đủ các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất từ True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, đến Matching, Summary Completion và Short-answer Questions. Điều này giúp bạn chuẩn bị toàn diện cho mọi tình huống trong bài thi.

Đáp án chi tiết với giải thích cụ thể: Phần giải thích đáp án không chỉ cho bạn biết câu trả lời đúng là gì mà còn chỉ ra chính xác vị trí trong bài, cách paraphrase, và lý do tại sao các đáp án khác sai. Đây là chìa khóa giúp bạn tự đánh giá và cải thiện kỹ năng.

Từ vựng chuyên ngành phong phú: Hơn 40 từ vựng quan trọng được trình bày chi tiết với phiên âm, nghĩa, ví dụ và collocation giúp bạn không chỉ hiểu nghĩa mà còn biết cách sử dụng trong ngữ cảnh.

Để đạt band điểm cao trong IELTS Reading với chủ đề này, hãy chú ý:

- Luyện tập quản lý thời gian hiệu quả (60 phút cho 40 câu)

- Nắm vững kỹ thuật skimming và scanning

- Chú ý đến paraphrase – đây là kỹ năng quan trọng nhất

- Xây dựng vốn từ vựng về công nghệ và xã hội

- Đọc nhiều bài viết học thuật về chủ đề tương tự

Hãy làm lại đề này nhiều lần, phân tích kỹ những câu sai và học từ vựng một cách bài bản. Chúc bạn đạt được band điểm mục tiêu trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!

[…] tác động này giúp chúng ta chuẩn bị tốt hơn cho tương lai, đặc biệt khi What are the social implications of increasing use of automation in manufacturing? cũng đang diễn ra song song trong các ngành công nghiệp […]