Mở bài

Trong xu thế toàn cầu hóa và công nghệ 4.0, vai trò của big data trong bảo vệ môi trường đang trở thành một chủ đề nóng hổi và xuất hiện ngày càng thường xuyên trong các đề thi IELTS Reading. Chủ đề này kết hợp giữa công nghệ, khoa học dữ liệu và vấn đề môi trường – ba lĩnh vực được ưa chuộng trong kỳ thi IELTS Academic. Qua phân tích các đề thi Cambridge IELTS từ tập 10 đến 19, chúng ta nhận thấy các bài đọc về công nghệ ứng dụng vào giải quyết vấn đề môi trường xuất hiện ít nhất 2-3 lần mỗi năm.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, bao gồm đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với nhiều dạng bài khác nhau như True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và Short-answer Questions. Mỗi câu hỏi đều đi kèm đáp án chính xác, giải thích chi tiết về vị trí thông tin trong bài, cách paraphrase và chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả. Bạn cũng sẽ được trang bị bộ từ vựng chuyên ngành quan trọng kèm phiên âm, nghĩa tiếng Việt và cách sử dụng thực tế.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, đặc biệt hữu ích cho những ai đang nhắm đến band điểm 6.5-7.5 và muốn làm quen với các chủ đề học thuật đương đại.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

Bài thi IELTS Reading kéo dài 60 phút cho 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, không có điểm âm cho câu trả lời sai. Độ khó của các passages tăng dần, với Passage 1 thường ở mức cơ bản, Passage 2 trung bình và Passage 3 khó nhất.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó Easy, Band 5.0-6.5)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó Medium, Band 6.0-7.5)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó Hard, Band 7.0-9.0)

Lưu ý quan trọng: Bạn nên dành 2-3 phút cuối để chuyển đáp án vào Answer Sheet, vì không có thời gian bổ sung cho việc này.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không được đề cập

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features – Nối thông tin với đặc điểm

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

Mỗi dạng câu hỏi yêu cầu kỹ năng đọc hiểu khác nhau, từ scanning (quét thông tin cụ thể) đến skimming (đọc lướt nắm ý chính) và detailed reading (đọc kỹ để hiểu sâu).

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – How Big Data is Transforming Wildlife Protection

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

In the past decade, conservationists have discovered a powerful new ally in their battle to protect endangered species: big data. This term refers to extremely large datasets that can be analyzed computationally to reveal patterns, trends, and associations. While big data has revolutionized industries from healthcare to finance, its application in environmental conservation is proving equally transformative.

Traditional wildlife monitoring methods were labour-intensive and often imprecise. Researchers would spend weeks in the field, manually counting animals or examining physical traces like footprints and droppings. These approaches, while valuable, could only provide snapshots of animal populations at specific times and locations. Moreover, they were expensive and sometimes disturbed the very ecosystems scientists were trying to study.

Today, the situation has changed dramatically. Sensor technologies, including camera traps, acoustic monitors, and satellite tracking devices, now generate massive amounts of data about wildlife behavior and habitat conditions. A single camera trap can capture thousands of images per week, while GPS collars on migrating animals transmit location data every few minutes. Drone surveillance adds another dimension, allowing researchers to survey vast areas that would be impossible to cover on foot.

The real breakthrough, however, comes not from collecting this data but from analyzing it effectively. Machine learning algorithms can now process millions of camera trap images, automatically identifying species, counting individuals, and even recognizing specific animals by their unique markings. What once required months of tedious manual work can now be accomplished in hours or days. This rapid processing enables scientists to respond quickly to emerging threats, such as poaching incidents or disease outbreaks.

One remarkable example comes from Africa, where big data is helping to protect elephants from ivory poachers. Conservation organizations have deployed networks of acoustic sensors that can detect gunshots from several kilometers away. When combined with predictive analytics based on historical poaching data, weather patterns, and moon phases, these systems can forecast where poaching is most likely to occur. Rangers can then be positioned strategically, dramatically improving their effectiveness.

Marine conservation has also benefited enormously from big data approaches. Scientists tracking whale populations traditionally relied on visual sightings from ships or aircraft, a method that provided only fragmentary information. Now, underwater microphones deployed across ocean basins record whale songs continuously. Advanced algorithms analyze these recordings to identify species, estimate population sizes, and track migration routes. This comprehensive data has revealed previously unknown whale populations and migration patterns, informing more effective protection strategies.

Furthermore, big data is helping conservationists understand how climate change affects ecosystems. By integrating data from weather stations, satellite imagery, and wildlife tracking devices, researchers can observe how animals respond to changing temperatures, rainfall patterns, and vegetation shifts. These insights are crucial for designing adaptation strategies and identifying which species are most vulnerable to climate disruption.

The technology is not without challenges, however. The cost of sensors and data processing infrastructure can be prohibitive for conservation projects in developing countries, where many biodiversity hotspots are located. There are also concerns about data security, particularly when information about endangered species locations could be exploited by poachers. Additionally, the sheer volume of data can be overwhelming, requiring specialized expertise to extract meaningful insights.

Despite these obstacles, the trajectory is clear. As technology becomes more affordable and accessible, big data will play an increasingly central role in conservation. Several international initiatives are now working to create open-source platforms where conservation organizations worldwide can share data and analytical tools. This collaborative approach promises to democratize access to cutting-edge technology, enabling even small organizations to benefit from big data insights.

Looking ahead, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things will further enhance conservation capabilities. Imagine sensors that not only detect animal presence but also monitor their stress levels through biochemical markers, or AI systems that can predict ecosystem collapse weeks before visible signs appear. These are not science fiction scenarios but realistic possibilities within the next decade.

The transformation of wildlife protection through big data represents a fundamental shift in how humans relate to the natural world. Rather than occasional observers, we are becoming continuous monitors and proactive guardians. This enhanced awareness brings both opportunity and responsibility. With unprecedented knowledge comes the power to prevent extinctions and restore ecosystems—but also the obligation to use that power wisely and ethically. As we continue to generate ever-larger datasets about our planet’s biodiversity, the question is not whether big data will change conservation, but how effectively we will harness it to protect the natural heritage we all depend upon.

Công nghệ camera bẫy giám sát động vật hoang dã qua phân tích dữ liệu lớn trong bảo tồn môi trường

Công nghệ camera bẫy giám sát động vật hoang dã qua phân tích dữ liệu lớn trong bảo tồn môi trường

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- Big data applications in conservation are as advanced as those in the healthcare industry.

- Traditional wildlife monitoring methods could only provide limited information about animal populations.

- Machine learning algorithms can identify individual animals from camera trap images.

- All conservation organizations now have access to big data technology.

- Poaching prediction systems in Africa consider weather conditions when forecasting illegal hunting activities.

Questions 6-9

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- In the past, wildlife researchers had to spend a long time in the field manually counting animals or examining __ like footprints.

- GPS collars on animals that migrate send __ several times per hour.

- Underwater recording devices help scientists track whale __ across oceans.

- Some conservation projects cannot afford big data technology because the __ is too high.

Questions 10-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, what is the main advantage of using machine learning for image analysis?

- A) It is cheaper than manual analysis

- B) It can identify more species than humans

- C) It processes data much faster than traditional methods

- D) It eliminates the need for camera traps

-

The acoustic sensors used in elephant conservation can:

- A) track individual elephants

- B) identify gunshots from long distances

- C) predict weather patterns

- D) communicate with rangers directly

-

What concern is mentioned regarding data security?

- A) Hackers might steal conservation funding

- B) Weather data could be inaccurate

- C) Poachers might access information about animal locations

- D) Sensors might stop working in remote areas

-

The passage suggests that future AI systems might be able to:

- A) replace all human conservationists

- B) detect ecosystem problems before they become visible

- C) eliminate poaching completely

- D) control animal behavior

PASSAGE 2 – The Data Revolution in Ocean Conservation

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The world’s oceans cover more than 70 percent of the Earth’s surface, yet they remain among the least understood environments on our planet. For centuries, the vastness and inaccessibility of marine ecosystems limited scientific understanding to what could be observed from ships or during brief submersible expeditions. This knowledge gap had serious implications for conservation efforts, as protecting something we barely understood proved exceptionally difficult. However, the advent of big data technologies is finally pulling back the curtain on the ocean’s mysteries, revolutionizing marine conservation in the process.

Central to this transformation is the proliferation of autonomous monitoring systems that can operate for extended periods without human intervention. Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) equipped with multiple sensors now patrol vast stretches of ocean, collecting data on water temperature, salinity, chemical composition, and biological activity. These robotic explorers can dive deeper and stay submerged longer than any human-operated vessel, accessing parts of the ocean that were previously beyond reach. Some AUVs are programmed to follow specific marine animals, documenting their behavior in unprecedented detail. Others conduct systematic surveys, creating comprehensive maps of seafloor topography and habitat distribution.

Complementing these underwater robots are satellite-based observation systems that monitor oceans from space. Advanced sensors can detect subtle changes in water color caused by phytoplankton blooms, identify coral reef bleaching events, track ocean currents, and even estimate fish population densities based on surface characteristics. When integrated with data from ship-based sensors, underwater monitors, and historical databases, these satellite observations provide a multi-dimensional view of ocean health that was unimaginable just two decades ago.

The scale of data generation is staggering. A single oceanographic research vessel on a month-long expedition might now collect more data than the entire global marine science community gathered in a year during the 1990s. This exponential growth in available information presents both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, researchers can now observe patterns and relationships that were invisible when data was scarce. On the other hand, extracting meaningful insights from such massive datasets requires sophisticated analytical tools and computational infrastructure that many research institutions struggle to provide.

Artificial intelligence has emerged as the key to unlocking the potential of marine big data. Neural networks trained on millions of underwater images can now identify thousands of marine species with accuracy rivaling expert taxonomists. These AI systems can process video footage from seafloor cameras, cataloging every organism that passes by and tracking changes in community composition over time. Similarly, machine learning algorithms analyze acoustic data from underwater microphones, distinguishing between the sounds of different whale species, boat engines, seismic surveys, and natural ocean noise. This automated analysis allows researchers to monitor marine ecosystems continuously rather than through periodic snapshots.

One particularly innovative application involves tracking illegal fishing activities. By analyzing satellite data on vessel movements combined with information about fishing regulations, protected areas, and known fishing patterns, algorithms can identify suspicious behavior that may indicate illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. When a vessel turns off its identification transponder in a protected area, travels at speeds consistent with trawling operations, or rendezvous with other ships in unusual patterns, these systems generate alerts for enforcement authorities. Several countries have successfully prosecuted IUU fishing operations based on such data-driven evidence.

Big data is also revealing the interconnectedness of ocean systems in ways that challenge previous conservation approaches. Traditional marine protected areas were often established based on limited data about specific species or habitats. Now, by analyzing movement patterns of multiple species, ocean current data, and nutrient distribution, scientists can identify critical connectivity corridors that link different marine ecosystems. A sea turtle might breed on beaches in one country, feed in coastal waters of another, and migrate through the territorial seas of several others. Effective protection requires international cooperation based on comprehensive data about these complex life cycles and movement patterns.

Climate change research has particularly benefited from oceanic big data. The ocean absorbs approximately 30 percent of human-generated carbon dioxide, making it a critical buffer against global warming. However, this absorption comes at a cost: ocean acidification, which threatens marine life from coral reefs to shellfish. Distributed sensor networks now monitor ocean pH levels, temperature, and carbon dioxide concentrations at thousands of locations worldwide. This data reveals not only global trends but also localized variations that help predict which marine ecosystems are most vulnerable to climate change impacts.

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain. The ocean environment is harsh on electronic equipment; sensors corrode, batteries fail, and devices are lost to storms or entanglement. Data transmission from underwater remains problematic, as radio waves don’t propagate well through water, limiting real-time communication. Many AUVs must surface periodically to transmit their data via satellite, creating gaps in monitoring coverage. Furthermore, the unequal distribution of monitoring technology means some ocean regions, particularly those around developing nations, remain relatively understudied despite often harboring exceptional biodiversity.

There are also emerging concerns about the environmental footprint of the monitoring infrastructure itself. Underwater acoustic monitors emit sounds that might disturb marine mammals. The production and eventual disposal of thousands of sensors raise questions about adding to ocean pollution. Some researchers advocate for a more judicious approach to data collection, focusing on strategic monitoring rather than attempting to measure everything everywhere.

Looking forward, the integration of big data with citizen science initiatives offers promising possibilities. Mobile apps now enable recreational divers, sailors, and beachgoers to contribute observations that, when aggregated, provide valuable information about marine species distribution and abundance. Fishing vessels are being equipped with sensors that collect oceanographic data during normal operations, transforming commercial fleets into a vast monitoring network. This democratization of data collection not only expands monitoring capacity but also engages broader communities in ocean conservation.

The transformation of marine conservation through big data represents a paradigm shift from reactive protection of threatened species to proactive ecosystem management based on comprehensive understanding. As our data collection and analytical capabilities continue to advance, we move closer to achieving what marine scientists call “ocean intelligence”—a real-time, comprehensive awareness of ocean conditions and trends that enables evidence-based policy and rapid response to emerging threats. Whether humanity will use this intelligence wisely remains an open question, but for the first time in history, we at least have the tools to truly understand and protect the marine realm that sustains all life on Earth.

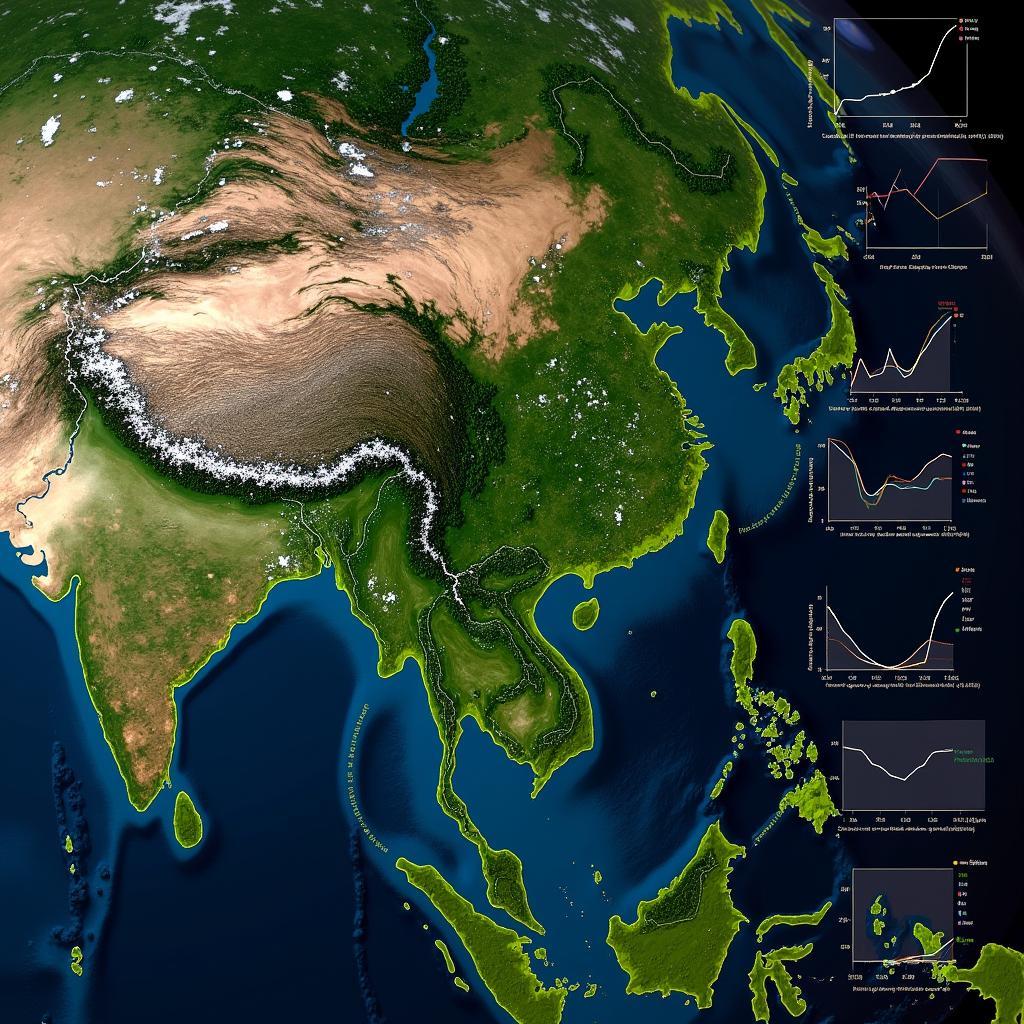

Phương tiện tự động dưới nước thu thập dữ liệu đại dương phục vụ bảo tồn biển thông qua big data

Phương tiện tự động dưới nước thu thập dữ liệu đại dương phục vụ bảo tồn biển thông qua big data

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to paragraph 1, what was the main obstacle to understanding ocean ecosystems?

- A) Lack of scientific interest

- B) Insufficient funding for research

- C) The difficulty of accessing marine environments

- D) Opposition from fishing industries

-

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) are advantageous because they can:

- A) operate independently for long periods

- B) replace all human researchers

- C) eliminate the need for ships

- D) predict future ocean conditions

-

What do satellite sensors detect to monitor ocean health?

- A) Individual fish movements

- B) Changes in water color indicating biological activity

- C) Underwater volcanic activity

- D) Ship communication signals

-

How do algorithms identify illegal fishing?

- A) By counting fish populations

- B) By analyzing weather patterns

- C) By detecting unusual vessel movement patterns

- D) By monitoring fish market prices

-

The passage suggests that traditional marine protected areas were:

- A) too large to be effective

- B) established with incomplete information

- C) opposed by local communities

- D) focused only on commercial species

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Big data has transformed ocean conservation by enabling continuous monitoring rather than periodic (19) __. Artificial intelligence, particularly (20) __ systems, can now identify marine species from images with expert-level accuracy. One important application is tracking (21) __ fishing by analyzing vessel movements. The ocean absorbs about 30% of carbon dioxide produced by humans, leading to (22) __, which threatens marine ecosystems. However, challenges remain, including equipment failure in harsh conditions and problems with (23) __ from underwater locations.

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Modern research vessels now collect more data in one month than was gathered globally per year in the 1990s.

- All countries have equal access to ocean monitoring technology.

- The environmental impact of monitoring equipment is negligible compared to its benefits.

PASSAGE 3 – Big Data Analytics and Terrestrial Ecosystem Management: Challenges and Opportunities

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The application of big data analytics to terrestrial ecosystem management represents a paradigmatic transformation in conservation science, one that promises to fundamentally alter humanity’s capacity to monitor, understand, and ultimately preserve the biosphere. However, this technological revolution brings with it a complex array of methodological challenges, ethical considerations, and practical limitations that warrant careful examination. As conservation organizations increasingly rely on data-driven approaches, critical questions emerge about the epistemological foundations of this new paradigm and whether the quantitative reductionism inherent in big data analysis might inadvertently obscure the holistic understanding necessary for effective ecosystem stewardship.

At its core, big data in conservation involves the aggregation and analysis of information from disparate sources: remote sensing satellites, ground-based sensor networks, citizen science observations, genomic databases, climate models, and socioeconomic datasets. The synthesis of these heterogeneous data streams requires sophisticated computational frameworks capable of handling not only the volume of information but also its variety and velocity—the so-called “three Vs” of big data. Contemporary conservation platforms increasingly employ cloud computing architectures and distributed processing systems that can integrate real-time data feeds with historical records, generating dynamic models of ecosystem state and trajectory.

The analytical methodologies applied to conservation big data have evolved considerably beyond simple descriptive statistics. Bayesian hierarchical models allow researchers to account for uncertainty and spatial autocorrelation in ecological data, while machine learning techniques such as random forests and convolutional neural networks excel at pattern recognition tasks like species identification from camera trap images or acoustic recordings. Ensemble modeling approaches combine predictions from multiple algorithms, often yielding more robust forecasts than any single method. Moreover, agent-based models and complex adaptive systems theory enable simulation of ecosystem dynamics under various scenarios, informing proactive management strategies rather than merely reactive interventions.

One particularly significant application domain involves the monitoring and management of deforestation and land use change. High-resolution satellite imagery, updated daily or even hourly, enables near-real-time detection of forest clearing events. Spectral analysis algorithms can distinguish between different types of vegetation, identify stressed or diseased trees before visible symptoms appear, and estimate carbon sequestration rates. When combined with socioeconomic data—including commodity prices, land ownership patterns, road development, and demographic trends—these systems can predict where deforestation is likely to occur, allowing preemptive interventions. Several tropical countries have implemented such systems with demonstrable success in reducing illegal logging and encroachment on protected areas.

However, the relationship between data volume and conservation effectiveness is not linear, and in some cases may exhibit diminishing returns or even counterproductive outcomes. The phenomenon of “data saturation” occurs when additional information fails to improve decision-making, either because key uncertainties are irreducible or because institutional capacity to act on insights is already saturated. Furthermore, an excessive focus on quantifiable metrics can lead to what critics term “metric fixation“—the tendency to prioritize easily measured variables while neglecting harder-to-quantify but potentially more important factors such as ecosystem resilience, cultural ecosystem services, or intrinsic biodiversity value.

The epistemological concerns surrounding big data in conservation extend beyond mere measurement to questions of knowledge production itself. Traditional ecological research emphasized hypothesis-driven investigation, with researchers formulating theories based on ecological principles and then designing experiments to test specific predictions. In contrast, big data approaches often employ exploratory data mining, allowing algorithms to discover patterns without a priori hypotheses. While this inductive approach can reveal unexpected relationships, critics argue it may identify spurious correlations lacking biological meaning. The distinction between correlation and causation becomes particularly problematic when machine learning models function as “black boxes,” generating accurate predictions through mechanisms that remain opaque even to their creators.

Data governance and ethical considerations pose additional challenges. Conservation datasets often contain sensitive information about endangered species locations, making them potential roadmaps for poachers if inadequately secured. Yet excessive data restriction can impede the collaborative research necessary for effective conservation. Striking an appropriate balance requires sophisticated access control systems and clear protocols for data sharing. Moreover, the asymmetric distribution of big data infrastructure creates power imbalances between well-funded institutions in developed countries and conservation practitioners in biodiversity-rich but data-poor regions. There is a risk that conservation priorities might be inadvertently skewed toward ecosystems and species for which data is abundant rather than those most urgently requiring protection.

The integration of Indigenous knowledge systems with big data analytics presents both opportunities and tensions. Indigenous peoples possess accumulated ecological wisdom developed over generations, often encompassing nuanced understanding of ecosystem dynamics that scientific data collection might miss. Some initiatives have successfully combined traditional ecological knowledge with sensor data and satellite imagery, creating more comprehensive pictures of ecosystem health. However, such integration must navigate complex issues of intellectual property rights, data sovereignty, and the incommensurability between different knowledge systems. There is a legitimate concern that big data approaches might marginalize or delegitimize Indigenous knowledge, reducing it to mere “ground-truthing” for technological systems rather than recognizing it as an independent and equally valid source of ecological understanding.

Predictive models based on big data have shown remarkable success in forecasting various ecological phenomena, from species range shifts under climate change to disease outbreak probabilities. However, the inherent unpredictability of complex ecological systems imposes fundamental limits on forecasting accuracy. Ecological systems exhibit non-linear dynamics, tipping points, and emergent properties that may not be apparent in historical data. A model trained on pre-disturbance conditions might fail catastrophically when the system crosses a critical threshold into a novel state. Additionally, the impact of unprecedented events—new invasive species, novel pathogens, or extreme climate anomalies outside the historical range—cannot be reliably predicted from past data alone.

Looking toward the future, several emerging technologies promise to further enhance big data capabilities in conservation. Environmental DNA (eDNA) sequencing allows species detection from water, soil, or air samples, potentially revolutionizing biodiversity monitoring. Quantum computing may eventually enable modeling of ecosystem complexity at scales currently impossible. The proliferation of low-cost sensors and Internet of Things devices will dramatically expand monitoring coverage. However, technological advancement alone cannot guarantee conservation success. The critical factor is not the volume of data collected or the sophistication of analytical tools, but rather the institutional capacity to translate insights into effective action, the political will to implement evidence-based policies, and the social engagement necessary to ensure conservation measures are equitable and sustainable.

The ultimate question confronting the conservation community is not whether to embrace big data—that ship has already sailed—but rather how to harness its power while remaining cognizant of its limitations. This requires what might be termed “critical data literacy“: an understanding not only of what big data can reveal but also of what it obscures, not only of the questions it answers but also of those it fails to ask. Effective conservation in the age of big data demands a synthetic approach that integrates quantitative analysis with qualitative understanding, technological capability with traditional knowledge, and computational power with ecological wisdom. Only through such integration can we hope to develop the comprehensive understanding necessary to preserve the planet’s imperiled ecosystems for future generations.

Giám sát phá rừng qua vệ tinh với phân tích big data về thay đổi sử dụng đất

Giám sát phá rừng qua vệ tinh với phân tích big data về thay đổi sử dụng đất

Questions 27-31

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

- Cloud computing architectures in conservation

- Bayesian hierarchical models

- Agent-based models

- Data saturation occurs when

- The phenomenon of “metric fixation” leads to

A enable researchers to consider uncertainty in ecological measurements.

B additional data no longer improves conservation decisions.

C prioritizing easily quantifiable factors over more important ones.

D simulate how ecosystems behave under different conditions.

E replace all traditional research methods.

F integrate multiple types of data in real-time.

G eliminate the need for field researchers.

H guarantee accurate long-term predictions.

Questions 32-36

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Big data approaches always produce better conservation outcomes than traditional research methods.

- Machine learning models sometimes generate accurate predictions through processes that are not fully understood.

- Indigenous knowledge has proven completely incompatible with big data systems.

- Ecological systems can undergo sudden changes that are difficult to predict from historical data.

- Most conservation organizations now have adequate funding for big data infrastructure.

Questions 37-40

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- What type of analysis can identify unhealthy trees before symptoms are visible to observers?

- What term describes the problem of confusing correlation with causation in big data?

- What kind of knowledge do Indigenous peoples possess that has been developed over many generations?

- According to the passage, what three factors beyond data collection are necessary for conservation success?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- physical traces

- location data

- migration routes

- cost / infrastructure cost

- C

- B

- C

- B

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- C

- A

- B

- C

- B

- snapshots

- neural network

- illegal

- ocean acidification

- data transmission

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- NOT GIVEN

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- F

- A

- D

- B

- C

- NO

- YES

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- Spectral analysis

- spurious correlations

- accumulated ecological wisdom / ecological wisdom

- institutional capacity, political will, social engagement (any three of these)

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: big data applications, conservation, healthcare industry, advanced

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn chỉ đề cập “big data has revolutionized industries from healthcare to finance” và ứng dụng trong bảo tồn “is proving equally transformative”. Tuy nhiên, không có thông tin so sánh mức độ tiên tiến (advanced) giữa hai lĩnh vực này. “Equally transformative” không có nghĩa là “equally advanced”.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: traditional methods, limited information, animal populations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, câu cuối

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “These approaches, while valuable, could only provide snapshots of animal populations at specific times and locations.” Từ “snapshots” được paraphrase thành “limited information” trong câu hỏi, xác nhận phát biểu này đúng.

Câu 3: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: machine learning algorithms, identify individual animals, unique markings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn khẳng định “Machine learning algorithms can now process millions of camera trap images, automatically identifying species, counting individuals, and even recognizing specific animals by their unique markings.” Điều này hoàn toàn khớp với phát biểu trong câu hỏi.

Câu 4: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all conservation organizations, access, big data technology

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ ra rõ ràng “The cost of sensors and data processing infrastructure can be prohibitive for conservation projects in developing countries”. Từ “prohibitive” (quá đắt, không thể chi trả) mâu thuẫn với “all organizations have access”, do đó câu trả lời là FALSE.

Câu 5: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: poaching prediction systems, Africa, weather patterns, forecasting

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nêu rõ “predictive analytics based on historical poaching data, weather patterns, and moon phases”. “Weather patterns” trong bài khớp chính xác với “weather conditions” trong câu hỏi.

Câu 6: physical traces

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: manually counting animals, examining

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, câu thứ 2

- Giải thích: “Researchers would spend weeks in the field, manually counting animals or examining physical traces like footprints and droppings.” Đây là thông tin rõ ràng, sử dụng đúng hai từ từ bài.

Câu 7: location data

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: GPS collars, migrating animals, transmit

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: “GPS collars on migrating animals transmit location data every few minutes.” Câu trong bài được paraphrase: “several times per hour” thay cho “every few minutes”, nhưng thông tin được truyền là “location data”.

Câu 8: migration routes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: underwater microphones, whale, track

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “Advanced algorithms analyze these recordings to identify species, estimate population sizes, and track migration routes.” Câu hỏi hỏi về việc theo dõi (track) điều gì, và đáp án là “migration routes”.

Câu 9: cost / infrastructure cost

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: conservation projects, cannot afford, technology

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: “The cost of sensors and data processing infrastructure can be prohibitive for conservation projects”. Từ “prohibitive” có nghĩa là quá cao không thể chi trả, trả lời cho câu hỏi về lý do tại sao không thể sử dụng công nghệ.

Câu 10: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: machine learning, image analysis, main advantage

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: “What once required months of tedious manual work can now be accomplished in hours or days. This rapid processing enables…” Lợi thế chính được nhấn mạnh là tốc độ xử lý nhanh hơn nhiều so với phương pháp truyền thống.

Câu 11: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: acoustic sensors, elephant conservation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “Conservation organizations have deployed networks of acoustic sensors that can detect gunshots from several kilometers away.” Đáp án B “identify gunshots from long distances” là paraphrase chính xác của thông tin này.

Câu 12: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: data security, concern

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: “There are also concerns about data security, particularly when information about endangered species locations could be exploited by poachers.” Mối lo ngại về an ninh dữ liệu liên quan đến việc thông tin vị trí động vật có thể bị thợ săn trộm khai thác.

Câu 13: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: future AI systems, might be able to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: “AI systems that can predict ecosystem collapse weeks before visible signs appear.” Đây là khả năng dự đoán vấn đề hệ sinh thái trước khi chúng trở nên rõ ràng, khớp với đáp án B.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main obstacle, understanding ocean ecosystems

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1

- Giải thích: “The vastness and inaccessibility of marine ecosystems limited scientific understanding to what could be observed from ships or during brief submersible expeditions.” Rào cản chính là sự khó tiếp cận (inaccessibility), tương ứng với đáp án C.

Câu 15: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: AUVs, advantageous

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: “Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) equipped with multiple sensors now patrol vast stretches of ocean, collecting data on… These robotic explorers can dive deeper and stay submerged longer than any human-operated vessel… Some AUVs are programmed to… without human intervention.” Lợi thế là hoạt động độc lập trong thời gian dài.

Câu 16: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: satellite sensors, detect, monitor ocean health

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: “Advanced sensors can detect subtle changes in water color caused by phytoplankton blooms, identify coral reef bleaching events…” Đáp án B đề cập đến thay đổi màu nước chỉ thị hoạt động sinh học.

Câu 17: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: algorithms, identify illegal fishing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “By analyzing satellite data on vessel movements combined with information about fishing regulations… algorithms can identify suspicious behavior… When a vessel turns off its identification transponder in a protected area, travels at speeds consistent with trawling operations…” Phát hiện thông qua phân tích mô hình di chuyển bất thường của tàu.

Câu 18: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: traditional marine protected areas

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7

- Giải thích: “Traditional marine protected areas were often established based on limited data about specific species or habitats.” Từ “limited data” cho thấy chúng được thiết lập với thông tin không đầy đủ.

Câu 19: snapshots

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: continuous monitoring, rather than periodic

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “This automated analysis allows researchers to monitor marine ecosystems continuously rather than through periodic snapshots.” Từ “snapshots” trong bài được sử dụng trực tiếp.

Câu 20: neural network

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: artificial intelligence, identify marine species

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “Neural networks trained on millions of underwater images can now identify thousands of marine species with accuracy rivaling expert taxonomists.”

Câu 21: illegal

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: tracking, fishing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, tiêu đề đoạn

- Giải thích: “One particularly innovative application involves tracking illegal fishing activities.”

Câu 22: ocean acidification

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: ocean absorbs, carbon dioxide, leading to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: “However, this absorption comes at a cost: ocean acidification, which threatens marine life from coral reefs to shellfish.”

Câu 23: data transmission

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: challenges, problems with, from underwater

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9

- Giải thích: “Data transmission from underwater remains problematic, as radio waves don’t propagate well through water, limiting real-time communication.”

Câu 24: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: research vessels, month, more data than, globally per year, 1990s

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: “A single oceanographic research vessel on a month-long expedition might now collect more data than the entire global marine science community gathered in a year during the 1990s.” Tác giả khẳng định điều này như một thực tế.

Câu 25: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all countries, equal access, ocean monitoring technology

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9

- Giải thích: Đoạn 9 đề cập “the unequal distribution of monitoring technology means some ocean regions, particularly those around developing nations, remain relatively understudied” nhưng không nói về tất cả các quốc gia hay so sánh trực tiếp mức độ tiếp cận công nghệ giữa các quốc gia.

Câu 26: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: environmental impact, monitoring equipment, negligible, compared to benefits

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: Đoạn 10 đề cập “There are also emerging concerns about the environmental footprint of the monitoring infrastructure itself” nhưng không so sánh tác động này với lợi ích hay nói nó là không đáng kể (negligible).

Giải thích đáp án chi tiết IELTS Reading về big data trong bảo tồn môi trường

Giải thích đáp án chi tiết IELTS Reading về big data trong bảo tồn môi trường

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: F

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: cloud computing architectures in conservation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: “Contemporary conservation platforms increasingly employ cloud computing architectures and distributed processing systems that can integrate real-time data feeds with historical records…” Đáp án F “integrate multiple types of data in real-time” paraphrase chính xác nội dung này.

Câu 28: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: Bayesian hierarchical models

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: “Bayesian hierarchical models allow researchers to account for uncertainty and spatial autocorrelation in ecological data…” Đáp án A “enable researchers to consider uncertainty in ecological measurements” là cách diễn đạt khác của thông tin này.

Câu 29: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: agent-based models

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: “Moreover, agent-based models and complex adaptive systems theory enable simulation of ecosystem dynamics under various scenarios…” Đáp án D “simulate how ecosystems behave under different conditions” paraphrase ý này.

Câu 30: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: data saturation occurs when

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “The phenomenon of ‘data saturation’ occurs when additional information fails to improve decision-making…” Đáp án B “additional data no longer improves conservation decisions” diễn đạt chính xác hiện tượng này.

Câu 31: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: metric fixation, leads to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “Furthermore, an excessive focus on quantifiable metrics can lead to what critics term ‘metric fixation’—the tendency to prioritize easily measured variables while neglecting harder-to-quantify but potentially more important factors…” Đáp án C chính xác mô tả hậu quả này.

Câu 32: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: big data approaches, always, better conservation outcomes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: Tác giả rõ ràng phản đối quan điểm này: “the relationship between data volume and conservation effectiveness is not linear, and in some cases may exhibit diminishing returns or even counterproductive outcomes.” Từ “always” trong câu hỏi mâu thuẫn với “not linear” và “counterproductive outcomes” trong bài.

Câu 33: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: machine learning models, accurate predictions, not fully understood

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “critics argue it may identify spurious correlations lacking biological meaning. The distinction between correlation and causation becomes particularly problematic when machine learning models function as ‘black boxes,’ generating accurate predictions through mechanisms that remain opaque even to their creators.” Tác giả xác nhận các mô hình có thể tạo ra dự đoán chính xác nhưng cơ chế vẫn không rõ ràng (opaque).

Câu 34: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Indigenous knowledge, completely incompatible, big data systems

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: “Some initiatives have successfully combined traditional ecological knowledge with sensor data and satellite imagery, creating more comprehensive pictures of ecosystem health.” Tác giả nêu ví dụ về việc kết hợp thành công, do đó phủ nhận tính “completely incompatible”.

Câu 35: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: ecological systems, sudden changes, difficult to predict, historical data

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9

- Giải thích: “Ecological systems exhibit non-linear dynamics, tipping points, and emergent properties that may not be apparent in historical data. A model trained on pre-disturbance conditions might fail catastrophically when the system crosses a critical threshold into a novel state.” Tác giả khẳng định hệ sinh thái có thể trải qua những thay đổi đột ngột (tipping points, critical thresholds) khó dự đoán từ dữ liệu lịch sử.

Câu 36: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: most conservation organizations, adequate funding, big data infrastructure

- Vị trí trong bài: Không có thông tin cụ thể

- Giải thích: Trong khi bài viết đề cập đến sự bất bình đẳng trong phân phối cơ sở hạ tầng big data và các vấn đề về chi phí, không có tuyên bố cụ thể nào về việc liệu “most” (phần lớn) tổ chức có nguồn tài trợ đầy đủ hay không.

Câu 37: Spectral analysis

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: identify unhealthy trees, before symptoms visible

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: “Spectral analysis algorithms can distinguish between different types of vegetation, identify stressed or diseased trees before visible symptoms appear…” Đây là loại phân tích cụ thể được đề cập.

Câu 38: spurious correlations

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: confusing correlation with causation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “While this inductive approach can reveal unexpected relationships, critics argue it may identify spurious correlations lacking biological meaning. The distinction between correlation and causation becomes particularly problematic…”

Câu 39: accumulated ecological wisdom / ecological wisdom

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: Indigenous peoples, knowledge, many generations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: “Indigenous peoples possess accumulated ecological wisdom developed over generations…” Có thể dùng cả cụm “accumulated ecological wisdom” hoặc “ecological wisdom” vì cả hai đều không quá 3 từ.

Câu 40: institutional capacity, political will, social engagement

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: three factors, beyond data collection, conservation success

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: “The critical factor is not the volume of data collected or the sophistication of analytical tools, but rather the institutional capacity to translate insights into effective action, the political will to implement evidence-based policies, and the social engagement necessary to ensure conservation measures are equitable and sustainable.” Ba yếu tố được liệt kê rõ ràng.

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conservationist | n | /ˌkɒnsəˈveɪʃənɪst/ | nhà bảo tồn thiên nhiên | Conservationists have discovered a powerful new ally | wildlife conservationist, marine conservationist |

| big data | n | /bɪɡ ˈdeɪtə/ | dữ liệu lớn, dữ liệu khổng lồ | Big data has revolutionized industries | big data analytics, big data technology |

| analyzed computationally | phrase | /ˈænəlaɪzd kəmˌpjuːtəˈʃənəli/ | phân tích bằng máy tính | Datasets that can be analyzed computationally | computational analysis, computational methods |

| labour-intensive | adj | /ˈleɪbər ɪnˈtensɪv/ | tốn nhiều sức lao động | Traditional methods were labour-intensive | labour-intensive process, labour-intensive work |

| snapshots | n | /ˈsnæpʃɒts/ | ảnh chụp nhanh, thông tin tại thời điểm nhất định | Could only provide snapshots of animal populations | data snapshots, population snapshots |

| sensor technologies | n | /ˈsensə tekˈnɒlədʒiz/ | công nghệ cảm biến | Sensor technologies now generate massive amounts of data | sensor networks, sensor deployment |

| machine learning algorithms | n | /məˈʃiːn ˈlɜːnɪŋ ˈælɡərɪðəmz/ | thuật toán học máy | Machine learning algorithms can process millions of images | machine learning models, machine learning techniques |

| poaching incidents | n | /ˈpəʊtʃɪŋ ˈɪnsɪdənts/ | vụ săn trộm động vật | Scientists can respond quickly to poaching incidents | prevent poaching, anti-poaching efforts |

| predictive analytics | n | /prɪˈdɪktɪv ænəˈlɪtɪks/ | phân tích dự đoán | When combined with predictive analytics | predictive models, predictive capabilities |

| biodiversity hotspots | n | /ˌbaɪəʊdaɪˈvɜːsəti ˈhɒtspɒts/ | các điểm nóng về đa dạng sinh học | Many biodiversity hotspots are located in developing countries | protect biodiversity hotspots, global biodiversity hotspots |

| artificial intelligence | n | /ˌɑːtɪˈfɪʃəl ɪnˈtelɪdʒəns/ | trí tuệ nhân tạo | Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence | AI systems, AI technology |

| enhanced awareness | n | /ɪnˈhɑːnst əˈweənəs/ | nhận thức nâng cao | This enhanced awareness brings both opportunity and responsibility | enhance awareness, awareness raising |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vastness and inaccessibility | n | /vɑːstnəs ənd ɪnækˌsesəˈbɪləti/ | sự rộng lớn và khó tiếp cận | The vastness and inaccessibility of marine ecosystems | ocean vastness, terrain inaccessibility |

| submersible expeditions | n | /səbˈmɜːsəbəl ekspəˈdɪʃənz/ | chuyến thám hiểm dưới nước | During brief submersible expeditions | underwater expeditions, deep-sea expeditions |

| advent | n | /ˈædvent/ | sự ra đời, sự xuất hiện | The advent of big data technologies | the advent of technology, advent of new era |

| autonomous underwater vehicles | n | /ɔːˈtɒnəməs ˈʌndəwɔːtə ˈviːɪkəlz/ | phương tiện tự động dưới nước | AUVs equipped with multiple sensors | deploy AUVs, AUV operations |

| subtle changes | n | /ˈsʌtl ˈtʃeɪndʒɪz/ | thay đổi tinh tế, thay đổi nhỏ | Sensors can detect subtle changes in water color | detect subtle changes, subtle variations |

| phytoplankton blooms | n | /ˌfaɪtəʊˈplæŋktən bluːmz/ | sự bùng nổ thực vật phù du | Changes caused by phytoplankton blooms | algal blooms, plankton blooms |

| multi-dimensional view | n | /ˌmʌltɪdaɪˈmenʃənəl vjuː/ | cái nhìn đa chiều | These observations provide a multi-dimensional view | multi-dimensional analysis, multi-dimensional approach |

| exponential growth | n | /ˌekspəˈnenʃəl ɡrəʊθ/ | tăng trưởng theo cấp số nhân | This exponential growth in available information | exponential increase, exponential expansion |

| extracting meaningful insights | phrase | /ɪkˈstræktɪŋ ˈmiːnɪŋfʊl ˈɪnsaɪts/ | rút ra những hiểu biết có ý nghĩa | Extracting meaningful insights from massive datasets | extract insights, gain insights |

| neural networks | n | /ˈnjʊərəl ˈnetwɜːks/ | mạng neural, mạng thần kinh nhân tạo | Neural networks trained on millions of images | deep neural networks, train neural networks |

| illegal fishing activities | n | /ɪˈliːɡəl ˈfɪʃɪŋ ækˈtɪvɪtiz/ | hoạt động đánh bắt cá bất hợp pháp | Tracking illegal fishing activities | combat illegal fishing, prevent illegal fishing |

| interconnectedness | n | /ˌɪntəkəˈnektɪdnəs/ | tính liên kết với nhau | The interconnectedness of ocean systems | ecosystem interconnectedness, global interconnectedness |

| distributed sensor networks | n | /dɪˈstrɪbjuːtɪd ˈsensə ˈnetwɜːks/ | mạng lưới cảm biến phân tán | Distributed sensor networks now monitor ocean pH levels | sensor network deployment, wireless sensor networks |

| localized variations | n | /ˈləʊkəlaɪzd veəriˈeɪʃənz/ | biến đổi cục bộ | This data reveals localized variations | local variations, regional variations |

| environmental footprint | n | /ɪnˌvaɪrənˈmentl ˈfʊtprɪnt/ | dấu chân môi trường, tác động môi trường | Concerns about the environmental footprint | reduce environmental footprint, carbon footprint |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paradigmatic transformation | n | /ˌpærədɪɡˈmætɪk trænsfəˈmeɪʃən/ | sự chuyển đổi mang tính mô thức | Represents a paradigmatic transformation | paradigm shift, transformational change |

| epistemological foundations | n | /ɪˌpɪstɪməˈlɒdʒɪkəl faʊnˈdeɪʃənz/ | nền tảng tri thức luận | Questions about the epistemological foundations | epistemological approach, epistemological framework |

| quantitative reductionism | n | /ˈkwɒntɪtətɪv rɪˈdʌkʃənɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa đơn giản hóa định lượng | The quantitative reductionism inherent in big data | reductionist approach, scientific reductionism |

| disparate sources | n | /ˈdɪspərət ˈsɔːsɪz/ | các nguồn khác nhau | Aggregation of information from disparate sources | disparate data, disparate elements |

| heterogeneous data streams | n | /ˌhetərəʊˈdʒiːniəs ˈdeɪtə striːmz/ | luồng dữ liệu không đồng nhất | Synthesis of these heterogeneous data streams | heterogeneous datasets, data heterogeneity |

| cloud computing architectures | n | /klaʊd kəmˈpjuːtɪŋ ˈɑːkɪtektʃəz/ | kiến trúc điện toán đám mây | Employ cloud computing architectures | cloud computing platforms, cloud infrastructure |

| Bayesian hierarchical models | n | /ˈbeɪziən ˌhaɪəˈrɑːkɪkəl ˈmɒdəlz/ | mô hình phân cấp Bayes | Bayesian hierarchical models allow researchers | Bayesian analysis, Bayesian statistics |

| spatial autocorrelation | n | /ˈspeɪʃəl ˌɔːtəʊkɒrɪˈleɪʃən/ | tự tương quan không gian | Account for spatial autocorrelation in ecological data | spatial patterns, spatial distribution |

| convolutional neural networks | n | /ˌkɒnvəˈluːʃənəl ˈnjʊərəl ˈnetwɜːks/ | mạng neural tích chập | Techniques such as convolutional neural networks | deep learning, neural network architecture |

| agent-based models | n | /ˈeɪdʒənt beɪst ˈmɒdəlz/ | mô hình dựa trên tác nhân | Agent-based models enable simulation | agent-based modeling, agent-based simulation |

| deforestation | n | /diːˌfɒrɪˈsteɪʃən/ | nạn phá rừng | Monitoring and management of deforestation | prevent deforestation, deforestation rates |

| spectral analysis | n | /ˈspektrəl əˈnæləsɪs/ | phân tích quang phổ | Spectral analysis algorithms can distinguish | spectral data, spectral imaging |

| carbon sequestration | n | /ˈkɑːbən ˌsiːkwəˈstreɪʃən/ | hấp thụ carbon | Estimate carbon sequestration rates | carbon storage, carbon capture |

| diminishing returns | n | /dɪˈmɪnɪʃɪŋ rɪˈtɜːnz/ | lợi ích giảm dần | May exhibit diminishing returns | law of diminishing returns, diminishing marginal returns |

| metric fixation | n | /ˈmetrɪk fɪkˈseɪʃən/ | sự ám ảnh về chỉ số | Critics term “metric fixation” | performance metrics, metric-driven |

| spurious correlations | n | /ˈspjʊəriəs ˌkɒrəˈleɪʃənz/ | tương quan giả | May identify spurious correlations | false correlations, correlation vs causation |

| black boxes | n | /blæk ˈbɒksɪz/ | hộp đen (thuật toán không rõ cơ chế) | Machine learning models function as black boxes | black box algorithms, black box systems |

| data governance | n | /ˈdeɪtə ˈɡʌvənəns/ | quản trị dữ liệu | Data governance and ethical considerations | data governance framework, data governance policies |

| Indigenous knowledge systems | n | /ɪnˈdɪdʒənəs ˈnɒlɪdʒ ˈsɪstəmz/ | hệ thống tri thức bản địa | Integration of Indigenous knowledge systems | traditional knowledge, Indigenous wisdom |

| intellectual property rights | n | /ˌɪntəˈlektʃuəl ˈprɒpəti raɪts/ | quyền sở hữu trí tuệ | Complex issues of intellectual property rights | IP rights, protect intellectual property |

| tipping points | n | /ˈtɪpɪŋ pɔɪnts/ | điểm chuyển hướng, ngưỡng quan trọng | Ecological systems exhibit tipping points | reach tipping point, critical tipping points |

| emergent properties | n | /ɪˈmɜːdʒənt ˈprɒpətiz/ | tính chất nổi lên | Tipping points and emergent properties | emergent behavior, emergent phenomena |

| environmental DNA | n | /ɪnˌvaɪrənˈmentl diː en eɪ/ | DNA môi trường | Environmental DNA (eDNA) sequencing | eDNA analysis, eDNA sampling |

| quantum computing | n | /ˈkwɒntəm kəmˈpjuːtɪŋ/ | máy tính lượng tử | Quantum computing may eventually enable | quantum computers, quantum technology |

| critical data literacy | n | /ˈkrɪtɪkəl ˈdeɪtə ˈlɪtərəsi/ | hiểu biết dữ liệu phê phán | Requires critical data literacy | data literacy skills, digital literacy |

Kết bài

Bài viết này đã cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với chủ đề “Big Data’s Role In Environmental Conservation” – một trong những chủ đề đương đại và ngày càng phổ biến trong các kỳ thi IELTS Academic. Qua ba passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy (Band 5.0-6.5) đến Medium (Band 6.0-7.5) và Hard (Band 7.0-9.0), bạn đã được làm quen với cách big data đang cách mạng hóa công tác bảo vệ môi trường – từ việc giám sát động vật hoang dã bằng công nghệ camera bẫy và GPS, đến ứng dụng AI trong bảo tồn đại dương, cho đến những thách thức tri thức luận và đạo đức khi áp dụng phân tích dữ liệu lớn vào quản lý hệ sinh thái trên cạn.

Bộ 40 câu hỏi đa dạng bao gồm True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, Matching Headings, Summary Completion, Matching Features và Short-answer Questions đã giúp bạn rèn luyện toàn diện các kỹ năng đọc hiểu cần thiết cho kỳ thi IELTS. Mỗi câu hỏi đều được thiết kế cẩn thận để phản ánh chính xác format và độ khó của đề thi thật, với đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích về vị trí thông tin trong bài và cách paraphrase.

Phần từ vựng chuyên ngành được tổng hợp theo từng passage không chỉ giúp bạn hiểu sâu hơn về nội dung bài đọc mà còn trang bị vốn từ quan trọng cho các chủ đề về công nghệ, môi trường và khoa học dữ liệu – những lĩnh vực thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS Reading. Hãy dành thời gian học kỹ các collocation và cách sử dụng thực tế của những từ này để áp dụng vào cả phần Writing và Speaking.

Để tối ưu hóa hiệu quả luyện tập, hãy làm bài trong điều kiện tương tự như thi thật: giới hạn thời gian 60 phút cho cả ba passages, không sử dụng từ điển, và chuyển đáp án vào Answer Sheet như quy định. Sau khi hoàn thành, hãy đối chiếu với đáp án, đọc kỹ phần giải thích để hiểu rõ lý do tại sao mỗi đáp án đúng hoặc sai, và phân tích những chỗ bạn còn yếu để cải thiện.

Chúc bạn đạt được band điểm mục tiêu trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!