Công nghệ blockchain đang dần thay đổi cách thức thương mại toàn cầu vận hành, từ việc theo dõi hàng hóa qua biên giới đến việc đơn giản hóa các giao dịch tài chính phức tạp. Chủ đề “Blockchain In Global Trade” ngày càng xuất hiện nhiều trong các đề thi IELTS Reading gần đây, phản ánh tầm quan trọng của xu hướng công nghệ này trong thế giới hiện đại.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages từ dễ đến khó, bao gồm:

- Passage 1 (Easy): Giới thiệu cơ bản về blockchain và ứng dụng thương mại

- Passage 2 (Medium): Phân tích các trường hợp thực tế và thách thức triển khai

- Passage 3 (Hard): Đánh giá tác động sâu rộng và triển vọng tương lai

Mỗi passage kèm theo 13-14 câu hỏi với các dạng bài đa dạng như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Matching Headings, và Summary Completion – hoàn toàn giống với đề thi thật. Đáp án chi tiết và giải thích cụ thể sẽ giúp bạn hiểu rõ phương pháp làm bài hiệu quả.

Bộ đề này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, muốn làm quen với chủ đề công nghệ trong bối cảnh kinh doanh quốc tế.

Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút và bao gồm 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Độ khó tăng dần từ Passage 1 đến Passage 3, yêu cầu thí sinh có khả năng đọc hiểu từ mức cơ bản đến nâng cao.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó Easy, band 5.0-6.5)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó Medium, band 6.0-7.5)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó Hard, band 7.0-9.0)

Lưu ý rằng không có thời gian bổ sung để chuyển đáp án sang Answer Sheet, vì vậy bạn cần quản lý thời gian cẩn thận và ghi đáp án trực tiếp trong khi làm bài.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Bộ đề thi này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Lựa chọn đáp án đúng từ các phương án cho sẵn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hay không được nhắc đến

- Yes/No/Not Given – Đánh giá quan điểm của tác giả

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn phù hợp

- Matching Headings – Chọn tiêu đề phù hợp cho mỗi đoạn

- Summary Completion – Điền từ để hoàn thành tóm tắt

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn bằng từ trong bài

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Basics of Blockchain Technology in Trade

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The modern global trade system involves countless transactions, multiple intermediaries, and mountains of paperwork. Each year, billions of dollars’ worth of goods cross international borders, but the process of tracking these items and verifying their authenticity remains surprisingly inefficient. Enter blockchain technology – a digital innovation that promises to revolutionize how we conduct international commerce.

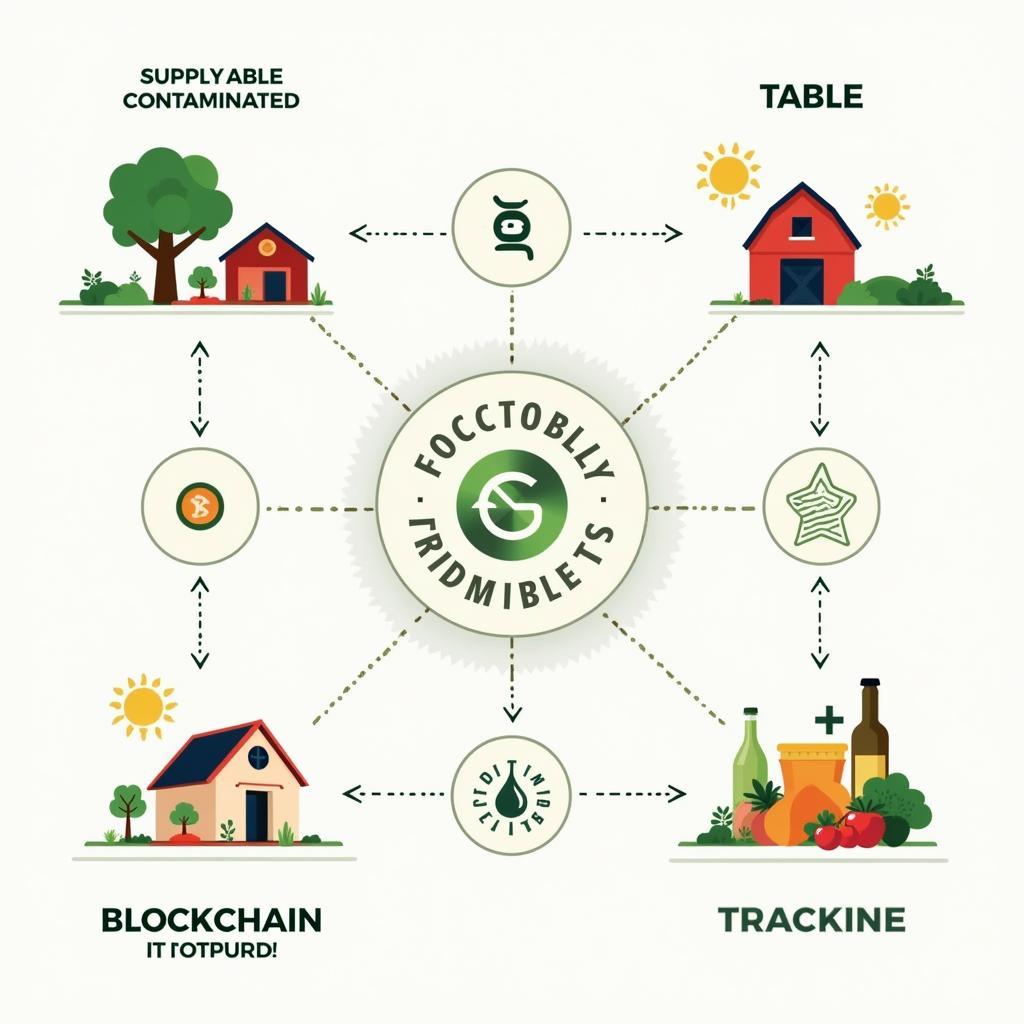

At its core, blockchain is a distributed ledger system that records transactions across multiple computers. Unlike traditional databases controlled by a single authority, blockchain creates a decentralized network where information is shared and verified by all participants. Think of it as a digital notebook that everyone can read, but no one can erase or alter without others knowing. Each “block” in the chain contains transaction data, and once added, it becomes a permanent record that cannot be changed retroactively.

The application of blockchain in global trade addresses several critical challenges. First, it dramatically reduces paperwork. A typical international shipment might require 30 different documents, including invoices, certificates of origin, and customs declarations. With blockchain, all these documents can be stored digitally in one secure, accessible location. Companies like Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping company, have already begun implementing blockchain systems to track their cargo. Their platform allows all parties involved – from manufacturers to customs officials – to access the same information simultaneously, eliminating delays caused by missing or incorrect documents.

Transparency is another major benefit. In traditional supply chains, it can be difficult to verify where products actually come from. This is particularly problematic for industries like food and pharmaceuticals, where product authenticity is crucial for consumer safety. Blockchain creates an immutable trail showing exactly where each item has been throughout its journey. If contaminated food is discovered, for example, authorities can quickly trace it back to its source and identify all affected batches within minutes rather than weeks.

The technology also enhances trust between trading partners who may not know each other well. In conventional trade, companies often rely on intermediaries such as banks and shipping agents to verify transactions and ensure goods are delivered as promised. These intermediaries add time and cost to every deal. Blockchain’s transparency means parties can verify information themselves, reducing the need for middlemen. Smart contracts – self-executing agreements written in computer code – can automatically release payments when certain conditions are met, such as when goods arrive at their destination.

For developing countries, blockchain offers particular advantages. Small businesses in these regions often struggle to access international markets because they lack the established relationships and financial credentials that larger companies possess. Blockchain can help level the playing field by providing a transparent record of their transactions and reliability. A small coffee farmer in Ethiopia, for instance, can use blockchain to prove the quality and origin of their beans directly to buyers in Europe, potentially commanding higher prices and building long-term relationships.

However, the technology is not without limitations. Implementing blockchain systems requires significant upfront investment in technology and training. Many companies, especially smaller ones, find the costs prohibitive. There are also questions about standardization – different blockchain platforms may not communicate with each other effectively, potentially creating new silos of information rather than the seamless integration that the technology promises.

Despite these challenges, the momentum behind blockchain in trade continues to build. The World Trade Organization has identified blockchain as a key technology for modernizing international commerce, and numerous pilot projects are underway worldwide. From tracking diamonds to verify they’re not funding conflicts, to monitoring pharmaceutical shipments to prevent counterfeits, the applications seem limitless. As the technology matures and becomes more affordable, blockchain may well become as fundamental to trade as shipping containers and cargo ships are today.

Questions 1-6

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- Blockchain technology allows any user to delete information from the system without detection.

- Maersk uses blockchain to enable different parties to view shipping information at the same time.

- Traditional supply chains can trace contaminated food to its source within hours.

- Smart contracts can automatically process payments when predefined conditions are fulfilled.

- Blockchain technology is currently too expensive for most large corporations to implement.

- The World Trade Organization believes blockchain will play an important role in future trade.

Questions 7-10

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- Blockchain is described as a __ that records transactions across many computers.

- In traditional trade, companies often use __ such as banks to verify transactions.

- Small businesses in developing countries often lack the __ that larger companies have.

- Different blockchain systems may not __ with each other properly, creating information silos.

Questions 11-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, what is a major advantage of blockchain for the food industry?

- A) It reduces the cost of food production

- B) It allows quick identification of contaminated products

- C) It improves the taste of food products

- D) It eliminates the need for food safety regulations

-

How does blockchain help small coffee farmers in developing countries?

- A) By providing them with free technology

- B) By eliminating all intermediaries in trade

- C) By proving their product’s quality and origin directly to buyers

- D) By guaranteeing them higher prices automatically

-

What is mentioned as a limitation of blockchain technology?

- A) It is too slow for modern trade requirements

- B) It cannot store important documents securely

- C) It requires substantial initial investment

- D) It is opposed by the World Trade Organization

PASSAGE 2 – Blockchain Implementation: Case Studies and Challenges

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The theoretical benefits of blockchain in global trade are compelling, but practical implementation reveals a more nuanced reality. As companies and governments experiment with this technology, they are discovering both unexpected opportunities and formidable obstacles that were not apparent when blockchain was merely a conceptual solution. Examining specific case studies provides valuable insights into how blockchain is actually transforming trade – and where it still falls short.

One of the most ambitious blockchain projects in international trade is TradeLens, a joint venture between Maersk and IBM launched in 2018. The platform aims to digitize the entire shipping ecosystem, connecting freight forwarders, port authorities, customs agencies, and thousands of other participants in the supply chain. By mid-2021, TradeLens had processed over 30 million shipping events and 20 million documents. The consortium approach – bringing together competitors and complementary businesses – has proven essential. Initially, some shipping companies were reluctant to join a platform partly owned by their rival Maersk, fearing it would provide competitive advantages. This trust deficit highlights a crucial challenge: blockchain requires collaboration among parties who traditionally compete, demanding a fundamental shift in corporate culture.

The food industry has emerged as another proving ground for blockchain technology. Walmart, in collaboration with IBM Food Trust, implemented a blockchain system to track produce from farm to store shelf. The results were striking: tracing the origin of mangoes, which previously took nearly seven days, could now be accomplished in 2.2 seconds. When Walmart discovered contaminated leafy greens linked to an E. coli outbreak, the blockchain system enabled them to identify affected products with unprecedented speed, potentially saving lives while minimizing unnecessary waste. The company has since mandated that suppliers of leafy green vegetables must upload their data to the blockchain, demonstrating how market power can drive adoption where voluntary participation might lag.

In the fashion industry, luxury brands face persistent problems with counterfeits that cost the sector an estimated $450 billion annually. LVMH, owner of brands like Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior, launched AURA, a blockchain platform that creates a digital certificate for each product, tracking it from raw materials through manufacturing to retail sale. Customers can verify authenticity by scanning a product with their smartphone. This application showcases blockchain’s potential beyond operational efficiency: it becomes a marketing tool that adds value by providing consumers with provenance information. However, the solution is only effective if counterfeiters cannot forge the digital tags themselves, revealing how blockchain solutions must be integrated with physical security measures.

Despite these successes, widespread adoption faces significant barriers. The interoperability problem remains acute. Multiple blockchain platforms exist – TradeLens, IBM Food Trust, AURA, and numerous others – each operating as isolated networks. A manufacturer might need to input the same information into several different systems to satisfy different trading partners, defeating blockchain’s promise of efficiency. Industry groups are working on standards to enable different blockchains to communicate, but progress has been slow, hampered by competing commercial interests and genuine technical complexities.

Regulatory uncertainty poses another challenge. The legal status of blockchain records varies across jurisdictions. While Estonia has amended its laws to recognize digitally signed documents on blockchain as legal evidence, many countries have yet to establish clear frameworks. This regulatory patchwork creates problems for international trade, where goods and documents cross multiple legal systems. A blockchain-verified certificate of origin might be accepted in one country but not in another, requiring traditional paper documentation as backup and negating efficiency gains.

The energy consumption associated with certain blockchain systems has also attracted criticism, particularly regarding environmental sustainability. Bitcoin, the most famous blockchain application, uses a “proof of work” system that requires enormous computational power, consuming as much electricity annually as some medium-sized countries. While the blockchain platforms designed for trade typically use more energy-efficient consensus mechanisms like “proof of stake,” concerns about environmental impact persist. Companies increasingly face pressure from investors and consumers to demonstrate sustainable practices, making the carbon footprint of their technology choices more relevant than ever.

Perhaps the most fundamental challenge is the human element. Blockchain systems require accurate data input at every stage. The technology can verify that information hasn’t been altered after being recorded, but it cannot verify that the information was correct initially – the “garbage in, garbage out” problem. If a farmer incorrectly labels conventional produce as organic when entering it into a blockchain system, the blockchain will faithfully preserve this fraudulent claim throughout the supply chain. This limitation means that blockchain must be complemented by traditional verification methods, including physical inspections and testing, rather than replacing them entirely.

Organizations contemplating blockchain adoption must also consider the change management required. Successful implementation demands that employees throughout the supply chain understand the new system and modify their workflows accordingly. Training costs can be substantial, and resistance to change is common, particularly among workers who have followed established procedures for decades. The psychological barriers to adoption – fear of job loss, comfort with familiar systems, skepticism about new technology – often prove more difficult to overcome than the technical hurdles.

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

What was a major concern for shipping companies about joining TradeLens?

- A) The technology was too complicated to understand

- B) Maersk might gain unfair competitive advantages

- C) The system was too expensive to implement

- D) Their rivals had better blockchain platforms

-

How did Walmart’s blockchain system improve food safety?

- A) By eliminating all contaminated produce

- B) By reducing the time needed to trace product origins

- C) By testing all food products automatically

- D) By preventing E. coli outbreaks entirely

-

According to the passage, the AURA platform created by LVMH

- A) has completely eliminated counterfeit luxury goods

- B) works independently without any physical security measures

- C) provides customers with information about product origins

- D) is used by all luxury brands worldwide

-

What does the passage say about Estonia?

- A) It has banned blockchain technology for legal documents

- B) It has modified laws to accept blockchain records as legal evidence

- C) It requires all international trade to use blockchain

- D) It has the world’s largest blockchain network

-

The “garbage in, garbage out” problem refers to

- A) the environmental waste created by blockchain systems

- B) the inability of blockchain to verify the accuracy of initial data entry

- C) the difficulty of deleting incorrect information from blockchain

- D) the energy consumption of proof of work systems

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

TradeLens represents a 19. __ where different companies work together on blockchain implementation. The system processes millions of shipping events and documents, but some companies were initially hesitant due to a 20. __ regarding Maersk’s involvement. In the food industry, Walmart used its 21. __ to require suppliers to use blockchain systems. For luxury goods, blockchain serves not only as an operational tool but also as a 22. __ that provides customers with additional information. However, successful implementation requires careful 23. __ to help employees adapt to new systems and processes.

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Different blockchain platforms can easily communicate with each other without technical problems.

- The environmental impact of blockchain technology is becoming increasingly important to companies.

- Physical inspections and testing will become unnecessary once blockchain is fully implemented in trade.

PASSAGE 3 – The Future Trajectory of Blockchain in International Commerce

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The discourse surrounding blockchain’s potential to revolutionize global trade has evolved considerably from the technological utopianism that characterized early discussions to a more pragmatic assessment of both transformative possibilities and inherent constraints. As we move beyond pilot projects to systemic integration, the question is no longer whether blockchain will reshape international commerce, but rather how this transformation will unfold and what structural reconfigurations it will necessitate in the geopolitical economy of trade. The implications extend far beyond operational efficiency, touching upon fundamental questions of economic power distribution, regulatory sovereignty, and the very nature of trust in commercial relationships.

Công nghệ Blockchain đang thay đổi cách thức vận hành thương mại quốc tế hiện đại

Công nghệ Blockchain đang thay đổi cách thức vận hành thương mại quốc tế hiện đại

The macroeconomic ramifications of widespread blockchain adoption in trade merit careful consideration. Traditional trade finance, worth approximately $9 trillion annually, relies heavily on documentary credit instruments such as letters of credit, which serve as risk mitigation mechanisms when parties lack mutual trust. Banks function as trusted intermediaries, verifying documents and guaranteeing payment, extracting fees for these services. Blockchain-based systems, by providing cryptographically secured, instantly verifiable transaction records, potentially disrupt this intermediation model. The implications for financial institutions are profound: as disintermediation reduces the need for traditional trade finance services, banks face existential pressure to reinvent their value proposition. Some financial institutions are responding by developing proprietary blockchain platforms, attempting to maintain their gatekeeping role in a decentralized technological environment – a strategy that some critics argue contradicts blockchain’s foundational ethos of openness.

The technology’s impact on developing economies presents a particularly complex analytical challenge. Proponents argue that blockchain could democratize access to international markets, enabling small-scale producers in emerging economies to bypass traditional intermediaries who have historically extracted disproportionate value from supply chains. A coffee cooperative in Rwanda, for instance, might use blockchain to demonstrate their compliance with fair trade standards and connect directly with roasters in developed markets, capturing more of the final sale price. This disintermediation narrative suggests blockchain could reduce inequality in global trade relationships. However, a critical examination reveals potential countervailing forces. The digital divide remains substantial; in many developing regions, reliable internet connectivity is sparse, and digital literacy is limited. Implementing blockchain systems requires not only technological infrastructure but also regulatory frameworks, technical expertise, and capital investment – resources that developing economies often lack. There is a risk that blockchain adoption could paradoxically exacerbate inequality, benefiting sophisticated actors who can navigate complex systems while marginalizing those without access to necessary resources. Furthermore, as the work of economist Dani Rodrik suggests, the promise of technological solutions to structural economic problems often obscures the political economy dimensions that fundamentally shape trade relationships.

Regulatory evolution represents another critical juncture. The question of how to regulate blockchain-based trade systems exemplifies broader tensions in internet governance: should regulation occur at national, regional, or global levels? National approaches risk creating a fragmented regulatory landscape that undermines blockchain’s potential for seamless international transactions. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for example, includes a “right to be forgotten,” which conflicts with blockchain’s immutable record-keeping. How can a company delete personal information from a blockchain if the technology’s core feature is permanent, unalterable records? This jurisdictional dilemma becomes more acute with cross-border transactions involving multiple legal systems with potentially contradictory requirements. Some scholars advocate for international treaty frameworks specifically addressing blockchain in trade, analogous to the legal architecture governing maritime shipping or aviation. However, achieving international consensus on technology regulation has proven notoriously difficult, as nations balance economic competitiveness with consumer protection, national security, and digital sovereignty concerns.

Similar to discussions around how is renewable energy influencing national security strategies?, the geopolitical dimensions of blockchain in trade are increasingly evident. Control over key blockchain infrastructure and standards could confer significant strategic advantages. China’s Blockchain Service Network, a state-backed initiative to create global blockchain infrastructure, represents an attempt to establish technical standards that could shape international commerce in ways favorable to Chinese interests. The United States and European Union, recognizing these strategic implications, have begun developing their own blockchain frameworks. This emerging competition over blockchain infrastructure parallels earlier contests over internet protocols and telecommunications standards, where technical specifications encoded geopolitical power. The concern extends to data sovereignty: if international trade increasingly relies on blockchain systems, who controls the data, where are the nodes located, and under what legal jurisdictions do they operate? These are not merely technical questions but matters of economic security and political autonomy.

The integration of blockchain with other emergent technologies promises to amplify both opportunities and challenges. The convergence of blockchain with the Internet of Things (IoT) could create autonomous supply chains where sensors automatically record temperature, location, and condition data directly onto blockchains, eliminating human data entry errors. Artificial intelligence algorithms could analyze blockchain-recorded trade patterns to optimize logistics and predict disruptions. However, this technological convergence also raises concerns about systemic vulnerability: highly integrated, automated systems may be more efficient but potentially more fragile, subject to cascading failures if critical components malfunction. Cybersecurity becomes paramount; a breach in interconnected blockchain-IoT-AI systems could compromise vast swathes of international commerce simultaneously.

Environmental considerations are increasingly foregrounding discussions about blockchain’s future, similar to how technological solutions to energy storage are being evaluated for sustainability. The energy intensity of some blockchain systems has sparked debate about whether the technology aligns with climate change mitigation goals. While newer consensus mechanisms substantially reduce energy consumption compared to Bitcoin’s proof-of-work system, the cumulative effect of scaling blockchain across global trade remains uncertain. Some researchers are exploring carbon-neutral blockchain architectures, powered by renewable energy or incorporating carbon offset mechanisms directly into the technology. The success of these initiatives will likely influence blockchain’s social license to operate, particularly as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations increasingly shape corporate decision-making and investor behavior.

Perhaps most fundamentally, blockchain’s evolution in trade will depend on whether it can deliver tangible value propositions that justify its complexity and cost. Early hype cycles often inflated expectations beyond what the technology could reasonably deliver, leading to disillusionment when results failed to match promises. The current phase might be characterized as realistic experimentation, where organizations implement blockchain for specific, well-defined use cases rather than pursuing wholesale transformation. This incremental approach may ultimately prove more sustainable than revolutionary rhetoric, allowing the technology to mature and demonstrating concrete benefits that build momentum for broader adoption. The trajectory of blockchain in trade, therefore, represents a dialectical process: technological capabilities enable new possibilities, but institutional inertia, regulatory constraints, economic incentives, and political considerations shape which possibilities are realized. Just as the role of government in regulating industry influences market development, understanding blockchain’s future requires analyzing not only the technology itself but the complex ecosystem in which it is embedded and the diverse stakeholders whose decisions will determine its ultimate impact on global commerce.

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, what is the main concern for banks regarding blockchain in trade finance?

- A) The technology is too expensive to implement

- B) Blockchain could eliminate their traditional intermediary role

- C) Their customers do not trust blockchain systems

- D) Governments are forcing them to adopt blockchain

-

The passage suggests that blockchain’s impact on developing economies

- A) will definitely reduce inequality in global trade

- B) has already proven successful in most regions

- C) could potentially worsen existing disparities

- D) is irrelevant to developed economies

-

What problem does GDPR create for blockchain systems?

- A) It requires companies to delete personal data, which contradicts blockchain’s immutable nature

- B) It bans all blockchain technology in the European Union

- C) It makes blockchain too expensive for European companies

- D) It requires all blockchain nodes to be located in Europe

-

China’s Blockchain Service Network is described as an attempt to

- A) help developing countries access international markets

- B) establish technical standards that favor Chinese interests

- C) cooperate with US and European blockchain initiatives

- D) reduce the cost of implementing blockchain technology

-

According to the passage, the current phase of blockchain implementation is characterized by

- A) revolutionary changes across all industries

- B) complete disillusionment with the technology

- C) realistic experimentation with specific use cases

- D) abandonment of the technology by major companies

Questions 32-36

Complete the summary using the list of words/phrases, A-L, below.

The future of blockchain in international trade involves more than just technological advancement. Banks face 32. __ as blockchain reduces the need for traditional intermediaries in trade finance. In developing nations, there is concern that blockchain could 33. __ rather than reduce it, due to lack of infrastructure and digital literacy. The question of 34. __ remains complicated, with different countries having conflicting requirements like the EU’s right to be forgotten. The technology’s integration with IoT and AI could create more efficient systems but also increases 35. __ to cyberattacks and system failures. The success of blockchain will ultimately depend on whether organizations can demonstrate 36. __ that justify its implementation costs.

A. regulatory frameworks

B. existential pressure

C. tangible value propositions

D. exacerbate inequality

E. economic growth

F. systemic vulnerability

G. profit margins

H. consumer demand

I. technological innovation

J. environmental standards

K. market competition

L. international cooperation

Questions 37-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- The coffee cooperative example demonstrates that blockchain will definitely benefit all small producers in developing countries.

- Technical specifications for blockchain infrastructure carry geopolitical significance beyond their technical functions.

- Most major corporations have already achieved carbon-neutral blockchain operations.

- Understanding blockchain’s future requires analyzing both the technology and the broader institutional context in which it operates.

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- distributed ledger

- intermediaries

- financial credentials

- communicate

- B

- C

- C

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- B

- B

- C

- B

- B

- consortium approach

- trust deficit

- market power

- marketing tool

- change management

- NO

- YES

- NO

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- A

- B

- C

- B

- D

- A

- F

- C

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- YES

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: blockchain, delete information, without detection

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “no one can erase or alter without others knowing” – không ai có thể xóa hoặc thay đổi mà người khác không biết. Đây là đặc điểm cốt lõi của blockchain, mâu thuẫn trực tiếp với câu phát biểu trong câu hỏi.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Maersk, different parties, view shipping information, same time

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ rõ “Their platform allows all parties involved – from manufacturers to customs officials – to access the same information simultaneously”. Đây là paraphrase của “view shipping information at the same time”.

Câu 4: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Smart contracts, automatically, payments, predefined conditions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài viết mô tả “Smart contracts – self-executing agreements written in computer code – can automatically release payments when certain conditions are met”. “Predefined conditions” là paraphrase của “certain conditions are met”.

Câu 7: distributed ledger

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: Blockchain, described as, records transactions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Câu mở đầu đoạn 2 nói “blockchain is a distributed ledger system that records transactions across multiple computers”.

Câu 11: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: major advantage, blockchain, food industry

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 5-8

- Giải thích: Bài viết giải thích “If contaminated food is discovered, for example, authorities can quickly trace it back to its source and identify all affected batches within minutes rather than weeks”. Đây chính là khả năng nhận diện nhanh chóng sản phẩm bị nhiễm độc.

Ứng dụng công nghệ Blockchain giúp truy xuất nguồn gốc thực phẩm nhanh chóng và chính xác

Ứng dụng công nghệ Blockchain giúp truy xuất nguồn gốc thực phẩm nhanh chóng và chính xác

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: shipping companies, concern, joining TradeLens

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ ra “some shipping companies were reluctant to join a platform partly owned by their rival Maersk, fearing it would provide competitive advantages”. “Competitive advantages” chính là “unfair competitive advantages” trong câu hỏi.

Câu 15: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Walmart’s blockchain system, improve food safety

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-6

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu rõ “tracing the origin of mangoes, which previously took nearly seven days, could now be accomplished in 2.2 seconds”. Việc giảm thời gian truy xuất từ gần 7 ngày xuống 2.2 giây chính là cải thiện về tốc độ truy xuất nguồn gốc sản phẩm.

Câu 18: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: garbage in garbage out problem

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết giải thích “The technology can verify that information hasn’t been altered after being recorded, but it cannot verify that the information was correct initially”. Đây là vấn đề về việc blockchain không thể xác minh tính chính xác của dữ liệu ban đầu.

Câu 19: consortium approach

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: TradeLens, different companies work together

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết sử dụng cụm “The consortium approach – bringing together competitors and complementary businesses”.

Câu 24: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Different blockchain platforms, easily communicate

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết khẳng định ngược lại: “The interoperability problem remains acute. Multiple blockchain platforms exist…each operating as isolated networks”. “Easily communicate” mâu thuẫn với “isolated networks” và “interoperability problem”.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main concern, banks, blockchain, trade finance

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-9

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu rõ “as disintermediation reduces the need for traditional trade finance services, banks face existential pressure to reinvent their value proposition”. “Existential pressure” cho thấy mối lo ngại lớn về vai trò trung gian truyền thống bị loại bỏ.

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: blockchain’s impact, developing economies

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 10-15

- Giải thích: Tác giả cảnh báo “There is a risk that blockchain adoption could paradoxically exacerbate inequality, benefiting sophisticated actors who can navigate complex systems while marginalizing those without access to necessary resources”. Từ “could” cho thấy đây là khả năng, không phải kết quả chắc chắn.

Câu 29: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: GDPR, problem, blockchain systems

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 6-9

- Giải thích: Bài viết giải thích mâu thuẫn: “The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for example, includes a ‘right to be forgotten,’ which conflicts with blockchain’s immutable record-keeping. How can a company delete personal information from a blockchain if the technology’s core feature is permanent, unalterable records?”

Câu 32: B (existential pressure)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Cụm từ “existential pressure” xuất hiện trong ngữ cảnh thảo luận về áp lực mà các ngân hàng phải đối mặt.

Câu 37: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: coffee cooperative, definitely benefit all small producers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: Tác giả chỉ đưa ra ví dụ về coffee cooperative như một khả năng (“might use blockchain”), sau đó chỉ ra nhiều rủi ro và thách thức. Từ “definitely” và “all” trong câu hỏi mâu thuẫn với giọng điệu thận trọng của tác giả.

Câu 40: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Understanding blockchain’s future, analyzing technology, broader institutional context

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn cuối, câu cuối cùng

- Giải thích: Tác giả kết luận “understanding blockchain’s future requires analyzing not only the technology itself but the complex ecosystem in which it is embedded and the diverse stakeholders whose decisions will determine its ultimate impact”. Đây chính xác là ý trong câu hỏi.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| distributed ledger | n | /dɪˈstrɪbjuːtɪd ˈledʒər/ | sổ cái phân tán | blockchain is a distributed ledger system | distributed ledger technology |

| decentralized | adj | /diːˈsentrəlaɪzd/ | phi tập trung | creates a decentralized network | decentralized system/network |

| intermediary | n | /ˌɪntəˈmiːdiəri/ | trung gian | rely on intermediaries such as banks | financial intermediary |

| transparent | adj | /trænsˈpærənt/ | minh bạch | Transparency is another major benefit | transparent process/system |

| immutable | adj | /ɪˈmjuːtəbl/ | bất biến, không thể thay đổi | creates an immutable trail | immutable record/data |

| smart contract | n | /smɑːrt ˈkɒntrækt/ | hợp đồng thông minh | Smart contracts can automatically release payments | execute smart contracts |

| authenticate | v | /ɔːˈθentɪkeɪt/ | xác thực | verify product authenticity | authenticate documents |

| upfront investment | n | /ˌʌpˈfrʌnt ɪnˈvestmənt/ | đầu tư ban đầu | requires significant upfront investment | make upfront investment |

| standardization | n | /ˌstændədaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | tiêu chuẩn hóa | questions about standardization | lack of standardization |

| credentials | n | /krɪˈdenʃlz/ | thông tin xác thực, bằng chứng | lack the financial credentials | financial credentials |

| seamless | adj | /ˈsiːmləs/ | liền mạch, liên tục | seamless integration | seamless transition |

| prohibitive | adj | /prəˈhɪbɪtɪv/ | quá cao, cản trở | find the costs prohibitive | prohibitively expensive |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nuanced | adj | /ˈnjuːɑːnst/ | tinh tế, nhiều sắc thái | a more nuanced reality | nuanced understanding |

| formidable | adj | /ˈfɔːmɪdəbl/ | đáng gờm, khó khăn | formidable obstacles | formidable challenge |

| consortium | n | /kənˈsɔːtiəm/ | hiệp hội, tập đoàn | The consortium approach | form a consortium |

| trust deficit | n | /trʌst ˈdefɪsɪt/ | thiếu hụt lòng tin | This trust deficit highlights | address trust deficit |

| proving ground | n | /ˈpruːvɪŋ ɡraʊnd/ | nơi thử nghiệm | emerged as another proving ground | serve as proving ground |

| counterfeit | n/adj | /ˈkaʊntəfɪt/ | hàng giả | persistent problems with counterfeits | counterfeit goods/products |

| provenance | n | /ˈprɒvənəns/ | nguồn gốc | providing consumers with provenance information | establish provenance |

| interoperability | n | /ˌɪntərˌɒpərəˈbɪləti/ | khả năng tương tác | The interoperability problem | ensure interoperability |

| regulatory uncertainty | n | /ˈreɡjələtəri ʌnˈsɜːtnti/ | sự không chắc chắn về quy định | Regulatory uncertainty poses | face regulatory uncertainty |

| jurisdictions | n | /ˌdʒʊərɪsˈdɪkʃnz/ | phạm vi pháp lý | varies across jurisdictions | multiple jurisdictions |

| energy consumption | n | /ˈenədʒi kənˈsʌmpʃn/ | tiêu thụ năng lượng | The energy consumption associated | reduce energy consumption |

| consensus mechanism | n | /kənˈsensəs ˈmekənɪzəm/ | cơ chế đồng thuận | energy-efficient consensus mechanisms | proof-of-stake consensus mechanism |

| change management | n | /tʃeɪndʒ ˈmænɪdʒmənt/ | quản lý thay đổi | also consider the change management | effective change management |

| garbage in, garbage out | phrase | /ˈɡɑːbɪdʒ ɪn ˈɡɑːbɪdʒ aʊt/ | rác vào rác ra (dữ liệu sai đầu vào sẽ cho kết quả sai) | the “garbage in, garbage out” problem | – |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| technological utopianism | n | /ˌteknəˈlɒdʒɪkl juːˈtəʊpiənɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa không tưởng công nghệ | characterized by technological utopianism | embrace technological utopianism |

| pragmatic assessment | n | /præɡˈmætɪk əˈsesmənt/ | đánh giá thực tế | a more pragmatic assessment | make pragmatic assessment |

| geopolitical economy | n | /ˌdʒiːəʊpəˈlɪtɪkl ɪˈkɒnəmi/ | kinh tế địa chính trị | in the geopolitical economy of trade | geopolitical economy framework |

| disintermediation | n | /ˌdɪsɪntəˌmiːdiˈeɪʃn/ | loại bỏ trung gian | as disintermediation reduces | process of disintermediation |

| existential pressure | n | /ˌeɡzɪˈstenʃl ˈpreʃə/ | áp lực tồn tại | banks face existential pressure | under existential pressure |

| countervailing forces | n | /ˌkaʊntəˈveɪlɪŋ ˈfɔːsɪz/ | lực lượng đối trọng | potential countervailing forces | face countervailing forces |

| digital divide | n | /ˈdɪdʒɪtl dɪˈvaɪd/ | khoảng cách số | The digital divide remains substantial | bridge the digital divide |

| exacerbate | v | /ɪɡˈzæsəbeɪt/ | làm trầm trọng thêm | could exacerbate inequality | exacerbate the problem |

| jurisdictional dilemma | n | /ˌdʒʊərɪsˈdɪkʃənl dɪˈlemə/ | tình thế khó xử về thẩm quyền | This jurisdictional dilemma | face jurisdictional dilemma |

| strategic advantages | n | /strəˈtiːdʒɪk ədˈvɑːntɪdʒɪz/ | lợi thế chiến lược | could confer significant strategic advantages | gain strategic advantages |

| data sovereignty | n | /ˈdeɪtə ˈsɒvrənti/ | chủ quyền dữ liệu | The concern extends to data sovereignty | protect data sovereignty |

| systemic vulnerability | n | /sɪˈstemɪk ˌvʌlnərəˈbɪləti/ | dễ bị tổn thương hệ thống | concerns about systemic vulnerability | reduce systemic vulnerability |

| cascading failures | n | /kæsˈkeɪdɪŋ ˈfeɪljəz/ | các sự cố dây chuyền | subject to cascading failures | prevent cascading failures |

| carbon-neutral | adj | /ˈkɑːbən ˈnjuːtrəl/ | trung hòa carbon | exploring carbon-neutral blockchain | achieve carbon-neutral operations |

| hype cycle | n | /haɪp ˈsaɪkl/ | chu kỳ cường điệu | Early hype cycles often inflated | through the hype cycle |

| tangible value proposition | n | /ˈtændʒəbl ˈvæljuː ˌprɒpəˈzɪʃn/ | giá trị đề xuất hữu hình | deliver tangible value propositions | demonstrate tangible value proposition |

| dialectical process | n | /ˌdaɪəˈlektɪkl ˈprəʊses/ | quá trình biện chứng | represents a dialectical process | undergo dialectical process |

| institutional inertia | n | /ˌɪnstɪˈtjuːʃənl ɪˈnɜːʃə/ | quán tính thể chế | institutional inertia | overcome institutional inertia |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề “Blockchain in global trade” không chỉ phản ánh xu hướng công nghệ hiện đại mà còn thể hiện sự giao thoa giữa kỹ thuật số, kinh tế và địa chính trị – những nội dung ngày càng phổ biến trong IELTS Reading. Bộ đề thi này đã cung cấp cho bạn trải nghiệm toàn diện với 3 passages tăng dần về độ khó:

- Passage 1 giới thiệu các khái niệm cơ bản về blockchain và ứng dụng trong thương mại

- Passage 2 đi sâu vào các trường hợp thực tế, thách thức triển khai và vấn đề liên ngành

- Passage 3 phân tích các chiều kích phức tạp về kinh tế, chính trị và tương lai của công nghệ

Với 40 câu hỏi đa dạng từ True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, đến Matching và Summary Completion, bạn đã được luyện tập đầy đủ các dạng bài quan trọng nhất của IELTS Reading. Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích vị trí và kỹ thuật paraphrase sẽ giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách tiếp cận từng loại câu hỏi một cách bài bản.

Hơn 45 từ vựng quan trọng được tổng hợp theo từng passage không chỉ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ học thuật mà còn cung cấp collocations hữu ích cho cả Writing và Speaking. Hãy ghi chú những từ mới và ôn tập thường xuyên để nâng cao band điểm tổng thể.

Chúc bạn luyện tập hiệu quả và đạt kết quả cao trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!

[…] goods as they move through the supply chain, and ensure compliance with customs regulations. The Blockchain in global trade offers enhanced security and reduces the risk of fraud, which has been a persistent problem in […]