Mở bài

Chủ đề Cultural Influences On Classroom Behavior Norms đề cập đến cách văn hóa định hình “chuẩn mực ứng xử” trong lớp học: từ giao tiếp bằng mắt, cách giơ tay phát biểu, đến việc làm việc nhóm hay thái độ với quyền lực của giáo viên. Đây là chủ đề được ưa chuộng trong IELTS Reading vì gắn với giáo dục, xã hội học và giao tiếp liên văn hóa, xuất hiện thường xuyên với các passage có độ khó tăng dần. Trong bài viết này, bạn sẽ luyện một đề thi mô phỏng sát thực tế gồm 3 passages (Easy → Medium → Hard), đa dạng dạng câu hỏi giống thi thật, kèm đáp án và giải thích chi tiết. Bạn cũng nhận được từ vựng trọng điểm và kỹ thuật làm bài hiệu quả để tăng tốc độ đọc hiểu, tránh bẫy paraphrase. Bài viết phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, đặc biệt hữu ích cho người muốn cải thiện điểm IELTS Reading test nhờ luyện tập bài tập IELTS Reading chất lượng cao và áp dụng IELTS Reading strategies.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

- Thời gian: 60 phút cho 3 passages

- Tổng số câu hỏi: 40 câu

- Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút

Mẹo nhanh:

- Đọc skim heading, topic sentence, keyword đậm/hoa, số liệu, tên riêng.

- Scan theo từ khóa paraphrase, tránh “dính bẫy” matching synonyms.

- Quản lý thời gian bằng cách “đóng khung” tối đa 90 giây cho một câu khó; đánh dấu, chuyển tiếp, quay lại sau.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

- Multiple Choice

- True/False/Not Given

- Sentence Completion

- Yes/No/Not Given

- Matching Headings

- Summary/Note Completion

- Matching Sentence Endings

- Short-answer Questions

Học về cultural influences on classroom behavior norms trong IELTS Reading

Học về cultural influences on classroom behavior norms trong IELTS Reading

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Quiet or Curious? How Culture Shapes Classroom Manners

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

In every classroom, students quickly learn what counts as “good behavior.” Yet these rules are not universal. They are shaped by culture, and culture travels with students when they cross borders. In some places, being quiet shows respect. In others, asking questions shows engagement. If we treat one style as “the only correct way,” we risk misunderstanding. Instead, we should see classroom behavior as a set of norms that different communities have learned over time.

Take eye contact. In many Western classrooms, looking at the teacher while listening signals attention. Teachers may even say, “Please look at me.” But in some traditions, making strong eye contact with an authority figure can feel disrespectful or confrontational. A student who looks down is not bored; they may be showing politeness. When teachers know this, they can judge attention by other signals, such as note-taking, nodding, or timely responses.

Turn-taking also varies. In classes where individualism is valued, students may jump into the conversation, volunteer answers, and debate ideas. Interrupting briefly can be read as enthusiasm. In classrooms shaped by collectivist values, students often wait for a clear invitation to speak. Silence can mean “I am thinking” or “I do not want to dominate.” It is not laziness. Teachers can balance both styles by setting explicit expectations: “Raise your hand,” “Use the chat to queue,” or “Take 60 seconds to think before sharing.”

Group work reveals more differences. Some students prefer to complete tasks alone and then compare results. Others feel safer learning in groups where everyone shares responsibility. In group-oriented classrooms, harmony is important. Publicly correcting a peer can cause loss of face. A teacher might encourage gentle feedback, such as “One thing I liked…” followed by “One suggestion is…,” which protects relationships while improving the work.

Attitudes toward authority also shape participation. In low power-distance contexts, students may treat the teacher as a facilitator. They ask “why,” challenge ideas, and expect detailed feedback. In higher power-distance settings, questioning can feel risky because it may look like criticizing the teacher. Students prefer private questions after class or via email. Teachers can offer multiple channels to ask questions: open discussion, anonymous forms, or short one-on-one meetings.

Even the meaning of “participation points” changes across cultures. Some students think participation equals “speaking often.” Others believe listening carefully and helping peers are equally valuable. If teachers define participation with a short rubric—for example, “ask one question, build on one idea, and summarize one point”—students from different backgrounds can participate fairly.

What can international students do? First, observe. Watch how classmates enter the room, take turns, and ask for help. Second, read the syllabus and ask for clarification. If you are unsure whether interrupting is acceptable, ask: “Would you prefer us to raise hands?” Third, keep your strengths: maybe you are very good at listening or at group coordination. Finally, be patient with yourself. You are not just learning content; you are learning a new classroom culture.

For teachers, cultural awareness is not about lowering standards but about making expectations visible. A simple slide at the start—“How we discuss,” “How we disagree,” “How we ask for help”—reduces confusion. Some instructors use think-pair-share, which gives quiet time before talking. Others invite rotating roles in groups—facilitator, timekeeper, note-taker—so that each student practices different skills. When students and teachers together build a shared set of classroom norms, learning becomes more inclusive and effective.

Bolded words in this passage clarify key ideas: norms, eye contact, politeness, individualism, collectivist, setting explicit expectations, harmony, power-distance, facilitator, feedback, rubric, clarification, and making expectations visible. These terms help us talk about behavior without blaming individuals, and they guide practical decisions in diverse classrooms.

Cultural influences on classroom behavior norms với eye contact và turn-taking

Cultural influences on classroom behavior norms với eye contact và turn-taking

Questions 1-13

Instructions:

- Questions 1-4: Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- Questions 5-9: Do the following statements agree with the information in the passage? Write True, False or Not Given.

- Questions 10-13: Complete the sentences. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage.

-

What is the main purpose of the passage?

A Explain a single correct way to behave in class

B Show how cultural norms influence classroom behavior

C Argue that silence is better than discussion

D Prove that participation points are unfair -

In some traditions, direct eye contact with a teacher can be seen as

A a sign of boredom

B a polite greeting

C confrontational behavior

D a way to request help -

In group-oriented classrooms, feedback is best given

A publicly and directly

B only by the teacher

C with gentle phrasing

D through written exams -

The author recommends that international students should

A keep silent to avoid mistakes

B observe and ask for clarification

C always challenge teachers

D avoid working in groups -

The passage states that one classroom rule works well in all cultures.

-

Silence can indicate careful thinking rather than laziness.

-

Students from collectivist cultures always speak softly in class.

-

Teachers in low power-distance settings may act as facilitators.

-

Students should completely change their own norms to fit the new class.

-

In some Western classrooms, making __ shows attentiveness.

-

A clear __ can define what participation means.

-

Teachers can reduce confusion by making __ visible.

-

One strategy that balances quiet and talk is __-pair-share.

PASSAGE 2 – Power Distance, Time, and Talk: Cultural Patterns in Learning

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

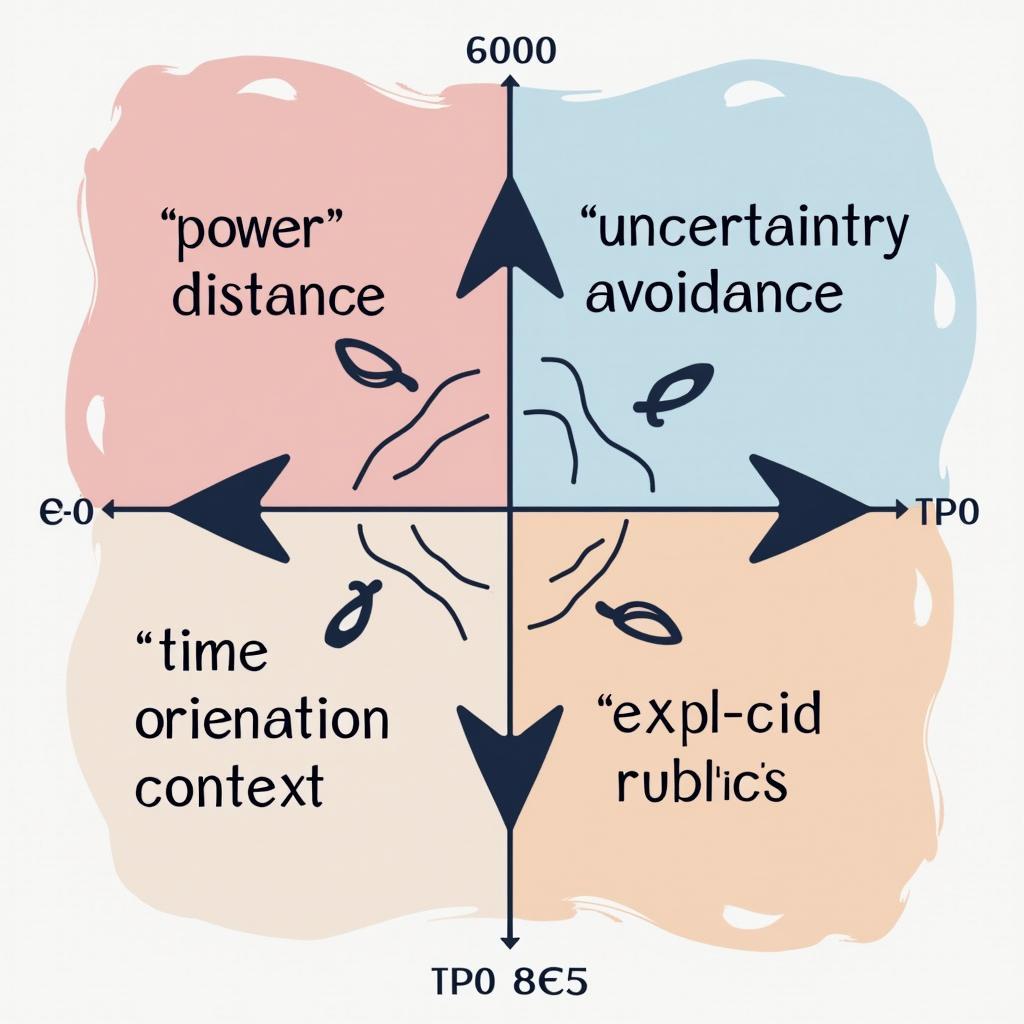

A In a global classroom, culture influences how students listen, ask questions, and respond to authority. Researchers often refer to broad dimensions—such as power distance, uncertainty avoidance, time orientation, and context of communication—to describe these patterns. While such models can be analytically useful, they require cautious use; no single learner fully represents a cultural average.

B In low power-distance environments, the teacher is expected to be a guide on the side, not a sage on the stage. Students may challenge claims and request justification. In high power-distance contexts, by contrast, public disagreement can be read as disloyalty. Students may prefer to seek clarification privately. When misunderstandings arise, it is often because participants interpret the same behavior through different cultural lenses.

C Uncertainty avoidance affects rules and risk-taking. Where uncertainty is disliked, students prefer clear rubrics, step-wise instructions, and tightly scaffolded tasks. They may delay speaking until they can ensure accuracy. In more uncertainty-tolerant settings, exploratory talk is valued, and partial ideas are welcomed. Silence here may signal deep processing rather than disengagement, especially when teachers allow longer wait time before calling on someone.

D Time orientation also shapes expectations. In monochronic cultures, punctuality and linear sequencing are central; classroom activities proceed in discrete stages, and deadlines are strict. In polychronic cultures, priorities can be more fluid; conversation overlaps and schedules adapt to relational needs. A teacher who recognizes these differences can improve pacing by stating time targets and responsibilities, while building flex points for discussion.

E Communication style matters. In high-context settings, much meaning is embedded in shared background and subtle cues; indirectness protects face. In low-context settings, explicit wording is preferred; direct feedback is not seen as hostile if phrased professionally. Cross-cultural classes benefit when instructors make feedback criteria transparent, provide models, and offer both public and private channels for questions.

F Assessment mirrors these values. Some systems reward assertive verbal participation; others reward meticulous written reasoning or group cohesion. A hybrid approach—participation points that include listening, synthesizing, and timely collaboration—reduces bias. Crucially, teachers can prompt equitable talk using structures like round-robin, think-pair-share, and nomination with wait time. When norms are co-constructed, students do not merely comply—they internalize the rationale.

Throughout, it is vital to remember that cultural frameworks describe tendencies, not immutabilities. Effective pedagogy begins with clarity and continues with adaptation.

Questions 14-26

Instructions:

- Questions 14-17: Do the following statements agree with the writer’s claims? Write Yes, No or Not Given.

- Questions 18-23: Matching Headings. Choose the correct heading for paragraphs A–F from the list of headings below.

- Questions 24-26: Complete the summary. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage.

Questions 14-17 (Yes/No/Not Given)

14. The writer believes cultural models should never be used in education.

15. In high power-distance cultures, public disagreement may be negatively perceived.

16. Longer wait time can help students who dislike uncertainty to participate.

17. Polychronic cultures always ignore deadlines.

List of Headings

i Benefits of transparent feedback and mixed channels

ii Cultural models: useful but limited

iii How power distance alters interpretations of disagreement

iv Why uncertainty avoidance changes talk and risk-taking

v The dominance of written assessment worldwide

vi Scheduling differences and pacing in class

vii The superiority of low-context communication

viii Aligning assessment with multiple participation behaviors

Questions 18-23 (Match A–F)

18. Paragraph A

19. Paragraph B

20. Paragraph C

21. Paragraph D

22. Paragraph E

23. Paragraph F

Summary Completion (Questions 24-26)

To support equitable participation, teachers can combine structures such as round-robin and think-pair-share with explicit criteria. This approach helps students not only follow procedures but also __ the reasons for them. Because cultural tendencies are not fixed, effective teaching requires both clarity and __. Additionally, in settings where uncertainty is disliked, providing detailed __ reduces hesitation.

Minh họa feedback minh bạch, power distance và time orientation trong lớp học quốc tế

Minh họa feedback minh bạch, power distance và time orientation trong lớp học quốc tế

PASSAGE 3 – Reframing Misbehavior: An Intercultural Pragmatics of Classroom Norms

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

When a student averts their gaze, answers cautiously, or avoids public disagreement, teachers in some settings may code this as disengagement. Yet such an interpretation often reflects a narrow, local script for “good participation.” The more productive question is not “Is this misbehavior?” but “Which interactional norms are being activated?” By shifting the unit of analysis from personality to pragmatics, we gain a framework for recalibrating expectations in culturally plural classrooms.

Attribution matters. The fundamental attribution error tempts observers to explain behavior through inner traits while overlooking situational cues. A student’s reluctance to interrupt may stem less from apathy than from high face-threat in public settings. In contexts that prioritize deference to expertise, a learner may exercise self-restraint to safeguard the teacher’s and peers’ positive face. What looks like passivity can conceal an ethic of relational responsibility.

Intercultural pragmatics examines how speakers manage speech acts—questioning, disagreeing, requesting—across cultures. In some traditions, a direct “Why?” presupposes equality of footing; elsewhere, it presupposes challenge. The same utterance thus performs different social actions. Students experiencing pragmatic transfer import familiar strategies (e.g., indirect questions, hedged proposals) that are sometimes reinterpreted. Without explicit teaching about local participation scripts, misalignments persist.

Accommodation theory predicts that interlocutors adjust their speech and turn-taking to converge or diverge. In classrooms, accommodation can be designed rather than left to chance. Teachers who articulate participation repertoires—for instance, “challenge by building,” “disagree by reframing,” or “ask via clarifying comparison”—equip students with linguistically scaffolded moves. Crucially, such repertoires include options for both high-visibility and low-visibility contributions, thereby broadening what “counts.”

Norms are not static; they are co-constructed. Through norm negotiation, participants craft shared procedures: timed think phases, distributed turn-allocation, or rotating roles that de-couple status from floor access. This is not mere etiquette. It is an equity technology that redistributes opportunities to display understanding. By making the interactional architecture teachable, instructors convert tacit expectations into curricular content.

Evidence supports the value of explicit norm instruction. In one quasi-experimental study, classes taught a short turn-taking protocol (comprising wait time, nomination sequences, and sentence starters) saw increased participation from students previously underrepresented in whole-class talk. Effects persisted when teachers embedded metacognitive reflection—students mapped which moves they used and when they felt invited to speak. Importantly, gains did not reduce the frequency of spontaneous debate; rather, they diversified its sources.

What, then, counts as misbehavior? The concept is indexical: it points to norms in play. Viewing behavior through an intercultural lens shifts the default from blame to design. If participation is uneven, the first lever is not personality remapping but task redesign. Provide private drafting time to lower face-threat; define “challenge” moves to normalize reasoned doubt; offer anonymous channels to elicit riskier questions; and align assessment with a multimodal definition of contribution (listening, synthesizing, questioning, coordinating). Only after such structural accommodations are in place does it make sense to attribute gaps to motivation.

Paradoxically, clarity expands freedom. When classes codify how to interrupt, how to cite disagreement respectfully, and how to request help, students import cultural strengths without penalty. The aim is not homogenization but orchestrated plurality: a classroom where divergent participation styles can co-exist, each legible within a shared grammar of interaction.

Questions 27-40

Instructions:

- Questions 27-31: Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- Questions 32-36: Matching Sentence Endings. Complete each sentence by choosing the correct ending (i–ix).

- Questions 37-40: Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS.

Multiple Choice (27-31)

27. The author argues that classroom “misbehavior” should be examined primarily as

A a failure of motivation

B a mismatch of interactional norms

C an individual personality flaw

D a disciplinary issue

-

According to the passage, pragmatic transfer refers to

A translating vocabulary incorrectly

B importing familiar interaction strategies into a new context

C failing to understand local grammar

D refusing to accommodate others -

The designed use of participation repertoires aims to

A eliminate disagreement

B restrict low-visibility contributions

C expand recognized ways of participating

D reduce teacher feedback -

The study on turn-taking protocols found that explicit instruction

A decreased spontaneous debate

B increased participation from previously quieter students

C had no long-term effects

D discouraged metacognitive reflection -

The passage suggests the first lever for uneven participation is

A stricter grading

B public correction

C task redesign

D excluding low-participation students

Matching Sentence Endings (32-36)

Choose the correct ending (i–ix) to complete each sentence. There are more endings than you need.

- The fundamental attribution error can cause teachers to

- In high face-threat contexts, students may

- Accommodation theory suggests participants

- Norm negotiation helps classrooms

- Structural accommodations should come before

Endings

i adopt rotating roles and shared turn allocation

ii interpret indirectness as clarity

iii adjust their speech and timing to others

iv misread situational behavior as stable traits

v abandon cultural strengths

vi show self-restraint to protect positive face

vii imposing blame for uneven participation

viii motivational judgments of students

ix rely solely on high-visibility talk

Short-answer Questions (37-40)

Answer NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS.

- What does the author call the set of options like “challenge by building”?

- What type of time helps lower face-threat before speaking?

- What kind of definition of contribution should assessment align with?

- What does the author call a classroom goal where different styles co-exist?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- C

- C

- B

- False

- True

- Not Given

- True

- False

- eye contact

- rubric

- expectations

- think

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- No

- Yes

- Yes

- No

- ii

- iii

- iv

- vi

- i

- viii

- internalize

- adaptation

- clear rubrics

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- B

- C

- B

- C

- iv

- vi

- iii

- i

- viii

- participation repertoires

- private drafting (time)

- multimodal

- orchestrated plurality

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

- Câu 1 (B): Dạng Multiple Choice; Từ khóa “norms shaped by culture”; Vị trí: đoạn 1. Bài không hề áp đặt một cách đúng duy nhất, mà nhấn mạnh ảnh hưởng văn hóa.

- Câu 2 (C): Eye contact có thể “disrespectful or confrontational”; Vị trí: đoạn 2.

- Câu 3 (C): Feedback “gentle phrasing”; Vị trí: đoạn 4.

- Câu 5 (False): Bài nói không có “one correct way”; Vị trí: đoạn 1.

- Câu 7 (Not Given): Không có thông tin “always speak softly”.

- Câu 10 (eye contact): In some Western classrooms, making eye contact shows attentiveness; Vị trí: đoạn 2.

- Câu 12 (expectations): “making expectations visible”; Vị trí: đoạn 7.

- Câu 13 (think): Tên cấu trúc “think-pair-share”; Vị trí: đoạn 7. Chỉ cần từ “think” theo hướng dẫn “NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS”; tuy nhiên đáp án tối ưu là “think” do cấu trúc gợi rõ.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

- Câu 14 (No): Tác giả nói “analytically useful… require cautious use”, không phải “never be used”; Vị trí: đoạn A.

- Câu 15 (Yes): Public disagreement có thể bị xem là disloyalty; Vị trí: đoạn B.

- Câu 16 (Yes): Longer wait time giúp; Vị trí: đoạn C.

- Câu 17 (No): Polychronic không đồng nghĩa “always ignore deadlines”; bài nêu “schedules adapt,” không phải bỏ qua; Vị trí: đoạn D.

- Matching Headings:

- A → ii (models useful but limited)

- B → iii (power distance and disagreement)

- C → iv (uncertainty avoidance)

- D → vi (scheduling differences)

- E → i (transparent feedback, mixed channels)

- F → viii (aligning assessment with multiple behaviors)

- Summary:

- 24 internalize; 25 adaptation; 26 clear rubrics; Vị trí: đoạn F và phần kết “not immutabilities… adaptation.”

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

- Câu 27 (B): “mismatch of interactional norms”; Vị trí: đoạn 1.

- Câu 28 (B): Pragmatic transfer = importing familiar strategies; Vị trí: đoạn 3.

- Câu 29 (C): Expand recognized ways; Vị trí: đoạn 4.

- Câu 30 (B): Increased participation by underrepresented students; Vị trí: đoạn 6.

- Câu 31 (C): “first lever… task redesign”; Vị trí: đoạn 7.

- Sentence Endings:

- 32–iv: fundamental attribution error → misread traits; đoạn 2.

- 33–vi: self-restraint to protect face; đoạn 2.

- 34–iii: adjust speech and timing; đoạn 4.

- 35–i: rotating roles and shared turn allocation; đoạn 5.

- 36–viii: structural fixes before motivational judgments; đoạn 7.

- Short answer:

- 37 participation repertoires; đoạn 4

- 38 private drafting (time); đoạn 7

- 39 multimodal; đoạn 7

- 40 orchestrated plurality; đoạn cuối

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| norm(s) | n | /nɔːrmz/ | chuẩn mực | “a set of norms” | social norms |

| eye contact | n | /ˈaɪ ˌkɒntækt/ | giao tiếp bằng mắt | “making eye contact” | maintain eye contact |

| confrontational | adj | /ˌkɒnfrʌnˈteɪʃənl/ | mang tính đối đầu | “can feel confrontational” | confrontational stance |

| politeness | n | /pəˈlaɪtnəs/ | lịch sự | “showing politeness” | politeness strategy |

| individualism | n | /ˌɪndɪˈvɪdʒuəlɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa cá nhân | “where individualism is valued” | individualism vs collectivism |

| collectivist | adj | /kəˈlektɪvɪst/ | đề cao tập thể | “collectivist values” | collectivist culture |

| explicit | adj | /ɪkˈsplɪsɪt/ | rõ ràng | “setting explicit expectations” | explicit instruction |

| harmony | n | /ˈhɑːməni/ | hòa hợp | “harmony is important” | social harmony |

| power-distance | n | /ˈpaʊər dɪstəns/ | khoảng cách quyền lực | “low power-distance contexts” | high/low power distance |

| facilitator | n | /fəˈsɪlɪteɪtər/ | người điều phối | “teacher as a facilitator” | act as facilitator |

| rubric | n | /ˈruːbrɪk/ | tiêu chí chấm điểm | “a short rubric” | assessment rubric |

| clarification | n | /ˌklærɪfɪˈkeɪʃn/ | làm rõ | “ask for clarification” | seek clarification |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| power distance | n | /ˈpaʊər ˈdɪstəns/ | khoảng cách quyền lực | “low power-distance environments” | reduce power distance |

| uncertainty avoidance | n | /ʌnˈsɜːrtnty əˈvɔɪdəns/ | né tránh bất định | “affects rules and risk-taking” | high/low uncertainty avoidance |

| time orientation | n | /taɪm ˌɔːriənˈteɪʃn/ | định hướng thời gian | “Time orientation also shapes expectations” | monochronic/polychronic |

| high-/low-context | adj | /haɪ/loʊ ˈkɒntekst/ | bối cảnh cao/thấp | “In high-context settings” | high-context culture |

| analytically useful | adj | /ˌænəˈlɪtɪkli ˈjuːsfl/ | hữu ích về phân tích | “can be analytically useful” | analytically useful model |

| justification | n | /ˌdʒʌstɪfɪˈkeɪʃn/ | biện minh | “request justification” | demand justification |

| scaffolded | adj | /ˈskæfəldɪd/ | được giàn dựng hỗ trợ | “tightly scaffolded tasks” | scaffolded instruction |

| accuracy | n | /ˈækjərəsi/ | độ chính xác | “ensure accuracy” | accuracy rate |

| wait time | n | /weɪt taɪm/ | thời gian chờ | “allow longer wait time” | increase wait time |

| monochronic | adj | /ˌmɒnəˈkrɒnɪk/ | đơn tuyến thời gian | “In monochronic cultures” | monochronic schedule |

| polychronic | adj | /ˌpɒlɪˈkrɒnɪk/ | đa tuyến thời gian | “In polychronic cultures” | polychronic rhythm |

| discrete | adj | /dɪˈskriːt/ | rời rạc | “discrete stages” | discrete phases |

| flex points | n | /fleks pɔɪnts/ | điểm linh hoạt | “build flex points” | flex points in pacing |

| meticulous | adj | /məˈtɪkjələs/ | tỉ mỉ | “meticulous written reasoning” | meticulous detail |

| internalize | v | /ɪnˈtɜːrnəlaɪz/ | nội tại hóa | “students internalize the rationale” | internalize norms |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| interactional norms | n | /ˌɪntərˈækʃənl nɔːrmz/ | chuẩn mực tương tác | “Which interactional norms are being activated?” | shared norms |

| pragmatics | n | /præɡˈmætɪks/ | ngữ dụng học | “shift… to pragmatics” | intercultural pragmatics |

| recalibrating | v | /ˌriːˈkæləbreɪtɪŋ/ | hiệu chỉnh lại | “framework for recalibrating expectations” | recalibrate expectations |

| fundamental attribution error | n | /ˌfʌndəˈmentl əˌtrɪbjuˈʃn ˈerər/ | lỗi quy gán cơ bản | “tempts observers to…” | commit the error |

| face-threat | n | /feɪs θret/ | mối đe dọa thể diện | “high face-threat” | reduce face-threat |

| positive face | n | /ˈpɒzətɪv feɪs/ | thể diện tích cực | “protect positive face” | save face |

| self-restraint | n | /ˌself rɪˈstreɪnt/ | tự kiềm chế | “exercise self-restraint” | display self-restraint |

| speech acts | n | /spiːtʃ ækts/ | hành vi ngôn ngữ | “manage speech acts” | perform a speech act |

| pragmatic transfer | n | /præɡˈmætɪk ˈtrænsfɜːr/ | chuyển giao ngữ dụng | “students experiencing pragmatic transfer” | negative transfer |

| accommodation theory | n | /əˌkɒməˈdeɪʃn ˈθɪəri/ | thuyết dung hợp | “predicts that interlocutors adjust…” | speech accommodation |

| repertoires | n | /ˈrepərtwɑːrz/ | vốn kỹ năng | “participation repertoires” | linguistic repertoires |

| scaffolded | adj | /ˈskæfəldɪd/ | được hỗ trợ từng bước | “linguistically scaffolded moves” | scaffolded practice |

| norm negotiation | n | /nɔːrm nɪˌɡoʊʃiˈeɪʃn/ | thương lượng chuẩn mực | “Through norm negotiation” | negotiate norms |

| interactional architecture | n | /ˌɪntərˈækʃənl ˈɑːrkɪtektʃər/ | kiến trúc tương tác | “make the interactional architecture teachable” | design architecture |

| turn-taking protocol | n | /tɜːrn ˈteɪkɪŋ ˈprəʊtəkɒl/ | quy ước luân phiên lượt nói | “taught a short turn-taking protocol” | follow a protocol |

| metacognitive reflection | n | /ˌmetəˈkɒɡnɪtɪv rɪˈflekʃn/ | phản tư siêu nhận thức | “embedded metacognitive reflection” | prompt reflection |

| multimodal | adj | /ˌmʌltiˈmoʊdl/ | đa phương thức | “multimodal definition of contribution” | multimodal assessment |

| orchestrated plurality | n | /ˌɔːrkɪˈstreɪtɪd pluːˈrælɪti/ | tính đa dạng được điều phối | “orchestrated plurality” | orchestrate plurality |

Kết bài

Cultural influences on classroom behavior norms là chủ đề then chốt trong IELTS Reading test vì đòi hỏi bạn nhận diện sự khác biệt văn hóa, theo dõi lập luận, và giải mã paraphrase. Bộ đề trên cung cấp 3 passages tăng dần độ khó, bao phủ nhiều dạng câu hỏi như thi thật, kèm đáp án và giải thích rõ ràng để bạn tự đánh giá và tối ưu chiến lược. Hãy luyện thường xuyên, ghi chú từ vựng học thuật, và áp dụng kỹ thuật skimming–scanning, nhận diện lập luận, cùng quản lý thời gian. Khi hiểu cách văn hóa định hình “chuẩn mực lớp học”, bạn sẽ đọc nhanh hơn, chính xác hơn, và tự tin chinh phục band điểm IELTS Reading. Tham khảo thêm các bài tập IELTS Reading và IELTS Reading tips tại [internal_link: chủ đề liên quan].