Mở Bài

Chủ đề về ảnh hưởng của văn hóa đến các chiến lược tham gia lớp học là một trong những chủ đề phổ biến trong IELTS Reading, đặc biệt xuất hiện nhiều trong các bài thi từ năm 2018 đến nay. Với sự đa dạng của các nền giáo dục toàn cầu và xu hướng học tập quốc tế ngày càng tăng, Cambridge và các tổ chức khảo thí IELTS thường đưa những bài đọc về giao tiếp đa văn hóa trong môi trường học thuật vào đề thi chính thức.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages từ dễ đến khó, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như thi thật. Bạn sẽ được luyện tập với các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Matching Information, và Summary Completion. Mỗi passage được thiết kế cẩn thận để phù hợp với độ khó tăng dần, giúp bạn làm quen với format thi thực tế.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, với đầy đủ đáp án chi tiết, giải thích cụ thể từng câu, và bảng từ vựng quan trọng kèm phiên âm. Đây là tài liệu lý tưởng để bạn tự đánh giá năng lực, hiểu rõ các kỹ thuật paraphrase, và nâng cao khả năng quản lý thời gian trong phòng thi.

Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Đây là bài thi đòi hỏi kỹ năng đọc hiểu, quét thông tin nhanh và quản lý thời gian hiệu quả. Mỗi passage có độ dài từ 650-1000 từ và độ khó tăng dần từ Passage 1 đến Passage 3.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (dễ nhất, nên làm nhanh để có thời gian cho các passage khó hơn)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình, cần đọc kỹ hơn)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (khó nhất, cần thời gian suy luận và phân tích)

Lưu ý quan trọng: Không có thời gian bổ sung để chép đáp án vào answer sheet, vì vậy bạn cần ghi đáp án trực tiếp trong khi làm bài.

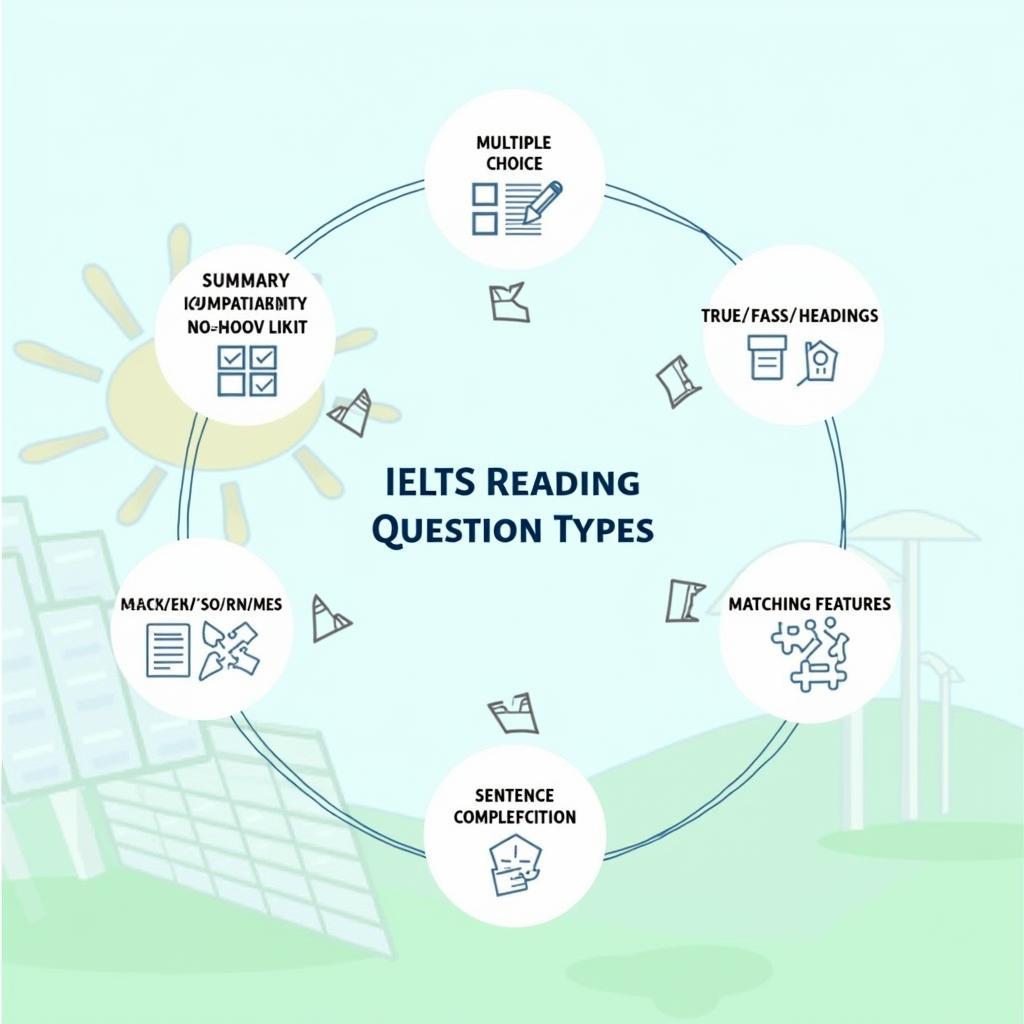

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Chọn đáp án đúng từ 3-4 lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hay không được đề cập

- Matching Information – Ghép thông tin với đoạn văn tương ứng

- Yes/No/Not Given – Xác định quan điểm của tác giả

- Matching Headings – Ghép tiêu đề phù hợp với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào chỗ trống trong đoạn tóm tắt

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn với số từ giới hạn

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Classroom Dynamics Across Cultures

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

In educational settings around the world, the ways students participate in classroom activities vary significantly depending on their cultural backgrounds. These differences in classroom participation strategies can have profound effects on learning outcomes and student-teacher relationships. Understanding these variations is becoming increasingly important as classrooms become more diverse and international education expands.

In many Western educational systems, particularly in North America and parts of Europe, active participation is highly valued and often forms part of a student’s grade. Students are encouraged to speak up, ask questions freely, and challenge ideas presented by teachers or textbooks. This approach stems from educational philosophies that emphasise critical thinking and individual expression. Teachers in these contexts typically view a quiet classroom as a sign that students are not engaged or interested in the material. Verbal contribution is seen as evidence of learning, and students who regularly participate in class discussions are often perceived as more intelligent or motivated.

However, this model of participation is not universal. In many Asian cultures, including China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, traditional educational values emphasise respect for authority and collective harmony over individual expression. Students from these backgrounds may be reluctant to speak in class, not because they lack understanding or interest, but because they have been taught that listening attentively and observing carefully are the primary ways to learn. In these cultures, asking questions might be seen as challenging the teacher’s authority or disrupting the flow of the lesson, which could bring shame not only to the student but also to their family.

The concept of “face” plays a crucial role in Asian classroom participation. Students may avoid speaking up because making a mistake in front of others could result in loss of face – a form of social embarrassment that is taken very seriously in collectivist cultures. Additionally, there is often a belief that one should only speak when one has something truly valuable to contribute, reflecting the proverb “empty vessels make the most noise.” This contrasts sharply with Western classrooms where brainstorming and thinking aloud are encouraged as part of the learning process, even if the ideas expressed are incomplete or incorrect.

Cultural differences in learning styles and student success cho thấy những khác biệt này không chỉ dừng lại ở cách thức tham gia mà còn ảnh hưởng sâu rộng đến toàn bộ quá trtrình học tập.

Middle Eastern educational traditions present yet another model. In many Arab countries, education has historically been based on memorisation and recitation of authoritative texts. Classroom participation often takes the form of students reciting passages they have memorised or demonstrating mastery of material through oral examination. Debate and discussion do occur, but they are typically more structured and formal than in Western classrooms, with clear rules about when and how students may speak.

Latin American educational cultures tend to fall somewhere between these extremes. While respect for teachers is important, there is also value placed on personal relationships and emotional expression in the classroom. Students may be more likely to participate when they feel a personal connection to the teacher or the material. Group work and collaborative learning are often emphasised, reflecting cultural values of community and interpersonal bonds.

These different approaches to classroom participation can create significant challenges in international education settings. When students from diverse cultural backgrounds come together in the same classroom, misunderstandings can arise. A teacher might interpret a quiet Asian student as disengaged, while the student believes they are showing respect. Similarly, a student accustomed to Western educational styles might be seen as disrespectful or overly aggressive in a more traditional classroom setting.

Educational researchers have begun to recognise that effective teaching in multicultural classrooms requires awareness of these differences and a willingness to adapt. Some strategies that have proven successful include providing multiple forms of participation (written responses, online discussions, small group work) rather than relying solely on verbal contributions in large group settings. Teachers can also give students more time to prepare responses, which accommodates those who come from cultures where thoughtful silence is valued over immediate response.

It is important to note that these are general patterns, and individual students may not conform to cultural stereotypes. Factors such as personality, previous educational experiences, and language proficiency all influence how students participate in class. Additionally, as globalisation continues and students are exposed to multiple educational systems, many are developing hybrid participation styles that combine elements from different cultural traditions.

The ultimate goal in addressing these differences is not to force students from one culture to adopt another’s participation style, but rather to create inclusive learning environments where diverse approaches to engagement are recognised and valued. This requires both teachers and students to develop cultural competence – the ability to understand, appreciate, and work effectively across cultural differences. As education becomes increasingly international, this skill will only grow in importance.

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

1. According to the passage, in Western educational systems, active participation is:

A. discouraged in most situations

B. considered evidence of learning

C. only important for language classes

D. measured solely through written work

2. The concept of “face” in Asian cultures refers to:

A. physical appearance in public

B. a type of classroom activity

C. social embarrassment and reputation

D. a teaching methodology

3. What does the proverb “empty vessels make the most noise” suggest?

A. Loud students are always wrong

B. Speaking should only occur when one has valuable contributions

C. Quiet students are more intelligent

D. Classroom noise should be minimised

4. In Middle Eastern educational traditions, classroom participation often involves:

A. challenging the teacher’s authority

B. informal debate and discussion

C. reciting memorised passages

D. remaining completely silent

5. According to the passage, effective teaching in multicultural classrooms requires:

A. forcing all students to adopt Western styles

B. ignoring cultural differences completely

C. separating students by cultural background

D. providing multiple forms of participation

Questions 6-10: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage? Write:

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

6. Western teachers often view quiet classrooms as a sign of student disengagement.

7. All Asian students are reluctant to participate in classroom discussions.

8. Latin American educational cultures place more emphasis on personal relationships than Asian cultures do.

9. Online discussions can be an effective alternative participation method for some students.

10. Most international students prefer Western-style classroom participation methods.

Questions 11-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

11. In collectivist cultures, making mistakes in front of others could result in __.

12. Educational researchers suggest that teachers should develop __ to work effectively across cultural differences.

13. Many students today are developing __ that combine elements from different cultural traditions.

PASSAGE 2 – The Psychology Behind Cultural Participation Patterns

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The stark contrasts in classroom participation across cultures are not merely superficial behavioural differences but are rooted in deep psychological frameworks shaped by centuries of social organisation and philosophical traditions. Understanding these underlying mechanisms provides valuable insights into how educational practices might be adapted to serve increasingly diverse student populations while respecting the cognitive and emotional needs of learners from different backgrounds.

A. At the heart of these differences lies the fundamental distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultural orientations, a framework extensively studied by cross-cultural psychologists such as Geert Hofstede and Harry Triandis. Individualistic cultures, predominant in Western societies, prioritise personal achievement, autonomy, and self-expression. Within this framework, the self is understood as an independent entity whose primary responsibility is to express unique qualities and achieve personal goals. Classroom participation becomes a natural extension of this worldview – an opportunity for students to distinguish themselves, demonstrate competence, and develop their individual voice.

B. Conversely, collectivistic cultures, common in Asia, Africa, and many Latin American countries, emphasise group harmony, interdependence, and social hierarchy. The self is conceptualised as fundamentally interconnected with others, and individual behaviour is evaluated based on how it affects the group. In educational settings shaped by these values, silence and attentive listening are not passive behaviours but active demonstrations of respect, humility, and commitment to collective learning. Speaking out, particularly in ways that might challenge authority or draw excessive attention to oneself, can be perceived as self-aggrandising and disruptive to group cohesion.

Cultural influences on student motivation and engagement đóng vai trò quan trọng trong việc hình thành những xu hướng tham gia khác nhau này.

C. The power distance dimension, another key concept in cultural psychology, further illuminates these patterns. Power distance refers to the extent to which less powerful members of institutions accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. In high power distance cultures, such as many Asian and Middle Eastern societies, there is greater acceptance of hierarchical structures and authoritarian teaching styles. Teachers are viewed as knowledge authorities whose role is to transmit information rather than facilitate discussion. Students in these contexts have been socialised to view questioning or disagreeing with a teacher as inappropriate and potentially offensive.

D. In contrast, low power distance cultures, typical of Scandinavia, Australia, and New Zealand, favour more egalitarian relationships between teachers and students. Education is seen as a collaborative endeavour where teachers and students work together to construct knowledge. This philosophical orientation encourages students to view their own perspectives as valuable and to engage in dialogue rather than unidirectional information transfer. The psychological comfort with questioning authority and expressing dissenting opinions is cultivated from early childhood in these societies.

E. Communication styles, categorised by anthropologist Edward T. Hall as “high-context” and “low-context,” also significantly influence classroom participation. High-context cultures, including most Asian and Arab societies, rely heavily on implicit communication, non-verbal cues, and shared understanding based on common cultural knowledge. In these settings, what is not said can be as important as what is explicitly stated. Students from high-context cultures may communicate understanding through subtle gestures, eye contact patterns, or slight nods rather than verbal affirmation.

F. Low-context cultures, such as those in North America and Germany, favour explicit, direct communication where meaning is conveyed primarily through words rather than context. In these educational environments, students are expected to articulate their thoughts clearly and directly, asking for clarification when needed and stating disagreement openly. The psychological discomfort that high-context culture students may experience when asked to communicate in this direct manner is often underestimated by teachers from low-context backgrounds.

G. Recent neuropsychological research has even suggested that cultural background may influence cognitive processing styles. Studies using brain imaging technology have found that individuals from Western cultures show greater activation in brain regions associated with individual object focus, while those from East Asian cultures show more activation in areas related to contextual and relational processing. While these findings are preliminary and subject to ongoing research, they suggest that cultural differences in classroom participation may have neurological correlates that extend beyond simple behavioural conditioning.

H. The implications of these psychological factors for education are profound. When students trained in collectivistic, high power distance, high-context educational systems enter Western universities, they face not merely a language barrier but a fundamental mismatch between their deeply internalised psychological frameworks and the participation expectations of their new environment. The anxiety and stress this creates can significantly impact academic performance and psychological wellbeing. Conversely, Western students in non-Western educational settings may be perceived as culturally insensitive or arrogant when they employ participation strategies that are valued in their home cultures.

Cultural influences on the perception of success in education cho thấy những khác biệt này ảnh hưởng không chỉ đến cách học mà còn đến cách định nghĩa thành công trong giáo dục.

Progressive educational institutions are beginning to address these challenges through culturally responsive pedagogy – teaching approaches that explicitly acknowledge and accommodate diverse participation styles. This might include structured talk protocols that give all students equal speaking opportunities, anonymous digital response systems that allow participation without public exposure, or culturally mixed small groups where students can learn from peers’ different approaches. Some universities now offer transition programmes that help international students understand and adapt to different participation norms while maintaining respect for their cultural values.

Importantly, researchers emphasise that the goal should not be cultural assimilation – forcing students to abandon their culturally shaped behaviours – but rather cultural addition, where students develop a repertoire of participation strategies they can deploy appropriately in different contexts. This bicultural competence is increasingly valuable in globalised professional environments where the ability to navigate multiple cultural frameworks is a significant asset.

Questions 14-19: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in the passage? Write:

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

14. Cultural differences in classroom participation are primarily superficial behavioural variations.

15. Brain imaging studies have definitively proven that culture changes brain structure.

16. Students from collectivistic cultures view silence as an active form of learning.

17. All Western educational systems have identical approaches to classroom participation.

18. Cultural assimilation should be the primary goal in addressing participation differences.

19. The ability to navigate multiple cultural frameworks is valuable in global careers.

Questions 20-23: Matching Headings

The passage has eight paragraphs, A-H. Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter, A-H.

20. A description of how meaning is conveyed differently across cultures

21. An explanation of how hierarchical structures affect student-teacher relationships

22. A discussion of potential biological bases for cultural differences

23. Examples of teaching methods that accommodate diverse participation styles

Questions 24-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Cross-cultural psychologists have identified that individualistic cultures prioritise (24) __ and self-expression, while collectivistic cultures emphasise group harmony. In high power distance cultures, teachers are seen as (25) __ who transmit information. Modern educational approaches aim to help students develop (26) __ so they can use different participation strategies in various contexts.

PASSAGE 3 – Reimagining Pedagogical Frameworks for Global Classrooms

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The exponential growth of international education, coupled with increased migration and the proliferation of multicultural societies, has rendered traditional monocultural pedagogical frameworks increasingly obsolete. The challenge facing contemporary educators extends far beyond superficial accommodation of diverse participation styles; it requires a fundamental reconceptualisation of what constitutes effective pedagogy in contexts where students bring radically different epistemological assumptions about the nature of knowledge, learning, and the student-teacher dynamic. This paradigm shift demands not merely methodological adjustments but a profound interrogation of the culturally contingent assumptions that underpin Western educational theory, which has historically positioned itself as universal despite being rooted in specific sociohistorical contexts.

The hegemonic dominance of Western educational philosophy in international academic discourse presents both practical and ethical challenges. Anglo-American constructivist pedagogies, which emphasise student-centred learning, discovery methods, and dialogic interaction, are frequently exported to non-Western contexts or imposed upon international students with insufficient consideration of their ontological compatibility with different cultural frameworks. This pedagogical imperialism, as some scholars have termed it, rests on unexamined assumptions about the universality of learning processes and the superiority of particular educational approaches. The implicit message that Western participation strategies represent the pinnacle of educational evolution – with other approaches viewed as deficient or underdeveloped – perpetuates neo-colonial dynamics within supposedly egalitarian educational spaces.

Cultural differences in approaches to science education minh chứng cho việc không có một phương pháp giáo dục nào có thể áp dụng phổ quát cho mọi bối cảnh văn hóa.

Critical pedagogy theorists argue that classroom participation patterns encode deeper questions about epistemology – how knowledge is constructed, validated, and transmitted. Western emphasis on verbalisation and explicit articulation reflects Cartesian philosophical traditions that privilege linguistic expression as the primary vehicle for thought and understanding. This logocentrism marginalises other modes of knowing that are privileged in different cultural traditions: the somatic knowledge emphasised in many indigenous educational systems, the contemplative understanding central to Buddhist educational philosophy, or the apprenticeship-based observational learning common in many African and Pacific Islander cultures. When classroom participation is assessed primarily through verbal contribution, students whose cultural backgrounds have cultivated alternative cognitive and expressive modalities are systematically disadvantaged.

Furthermore, the Western construction of classroom participation as individual performance fails to accommodate collective cognition – the concept that thinking and learning can be fundamentally distributed across social groups rather than localised within individual minds. This concept, which has gained traction in sociocultural learning theory, resonates strongly with educational practices in cultures that emphasise communal knowledge construction. In these frameworks, an individual’s silence during large-group discussions is not indicative of non-participation; rather, they may be actively engaged in collective sense-making processes that manifest in different communicative forms – through subsequent actions, small-group elaborations, or practical applications rather than immediate verbal responses.

The neurodiversity movement offers a productive parallel to cultural diversity in education. Just as educators have increasingly recognised that neurotypical communication and participation norms may not suit all learners regardless of intelligence or capability, there is growing acknowledgment that culture-specific participation norms reflect different but equally valid approaches to learning. This perspective challenges the deficit model that has historically framed non-Western participation styles as problems to be corrected rather than as alternative pedagogical resources that might enrich educational environments for all students.

Several theoretical frameworks have emerged to address these complexities. Third space theory, developed by scholars such as Homi Bhabha and applied to education by Kris Gutierrez, proposes that multicultural classrooms can become spaces where hybrid practices emerge that are not simply compromises between different cultural norms but genuinely new forms of educational engagement that transcend their constituent traditions. Rather than asking students to code-switch between cultural participation styles or requiring them to abandon their culturally preferred approaches, third space pedagogy seeks to create conditions where diverse participation modes can coexist and mutually inform one another, generating innovative educational practices that might not emerge in culturally homogeneous settings.

Translanguaging theory, originally developed in multilingual education, offers analogous possibilities for classroom participation. Just as translanguaging recognises that multilingual speakers do not separate their languages into discrete systems but rather draw upon their full linguistic repertoire as an integrated communicative resource, a “transparticipation” approach might encourage students to deploy their full range of culturally-shaped participation strategies fluidly rather than conforming to a single prescribed mode. This might mean combining verbal and non-verbal communication, alternating between individual and collaborative response formats, or integrating reflective pauses with dynamic discussion.

The role of education in promoting sustainable practices cũng cần xem xét đến sự đa dạng về văn hóa khi thiết kế các chương trình giáo dục toàn cầu.

Implementing such theoretically sophisticated approaches in practice requires substantial institutional support and teacher education. Most teacher training programmes in Western contexts provide minimal preparation for culturally responsive pedagogy, often limiting discussion of diversity to superficial cultural awareness rather than engaging with the deeper epistemological and pedagogical implications. Teachers need not only knowledge about different cultural participation norms but also critical reflexivity regarding their own culturally-shaped assumptions, the ability to facilitate meta-discussions about participation with students, and skills in designing structurally inclusive activities rather than relying on individual adaptation.

Assessment systems represent another significant challenge. If classroom participation constitutes a graded component of a course – as it does in many Western educational contexts – students from cultures that do not value verbal performance face systematic disadvantage regardless of their conceptual understanding or overall capability. More equitable approaches might include multiple participation pathways in assessment criteria, recognition of different forms of contribution (preparation of materials, synthesis of ideas, facilitation of group processes), or process-oriented assessment that recognises learning trajectories rather than instantaneous performance.

The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting shift to online education has inadvertently highlighted both challenges and opportunities in this domain. Digital platforms can mitigate some cultural barriers to participation – asynchronous discussion forums allow students from cultures that value careful deliberation more time to formulate responses, while anonymous polling and digital response systems can reduce the face-threat associated with public speaking for some students. However, online education has also exposed digital divides and created new forms of participation inequality based on technological access and digital literacy, which often correlate with socioeconomic and cultural factors.

Moving forward, the field requires robust empirical research that moves beyond comparative deficit models to investigate the cognitive and pedagogical affordances of different participation approaches. Rather than asking how to help “quiet Asian students” become more like “talkative Western students,” research might explore what pedagogical benefits different participation styles offer, how diverse approaches can be leveraged to enhance collective learning, and what forms of institutional flexibility best serve truly inclusive education. Such research must involve scholars from diverse cultural backgrounds in equitable partnerships rather than perpetuating patterns where Western researchers study non-Western educational practices as exotic phenomena.

Ultimately, addressing Cultural Influences On Classroom Participation Strategies represents not merely a practical accommodation to demographic realities but an opportunity to fundamentally improve educational quality for all students. Classrooms that successfully integrate multiple participation frameworks model the intercultural competence increasingly essential in globalised societies, challenge students to examine their own cultural assumptions, and create richer learning environments where diverse perspectives genuinely contribute to collective knowledge construction rather than being superficially acknowledged and then marginalised in actual pedagogical practice.

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

27. According to the passage, Western educational philosophy in international contexts is problematic because it:

A. is too difficult for non-Western students to understand

B. assumes universal applicability despite cultural specificity

C. requires too much teacher training to implement

D. focuses exclusively on scientific knowledge

28. The term “logocentrism” in the passage refers to:

A. the use of logic in classroom discussions

B. the privileging of linguistic expression as the primary mode of understanding

C. a teaching method developed in Greece

D. the practice of keeping detailed classroom records

29. According to collective cognition theory, an individual’s silence during discussion may indicate:

A. lack of intelligence or understanding

B. disrespect for the teacher

C. active engagement in group sense-making processes

D. inability to speak the language fluently

30. Third space theory proposes that multicultural classrooms can:

A. require students to abandon their cultural practices

B. separate students by cultural background

C. generate genuinely new forms of educational engagement

D. eliminate all cultural differences

31. The passage suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic’s shift to online education:

A. solved all cultural participation challenges

B. created only negative outcomes for diverse students

C. revealed both opportunities and new inequalities

D. had no impact on classroom participation patterns

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each theoretical concept (Questions 32-36) with the correct description (A-H). Write the correct letter, A-H.

Theoretical Concepts:

32. Pedagogical imperialism

33. Somatic knowledge

34. Translanguaging

35. Third space theory

36. Transparticipation

Descriptions:

A. Drawing upon multiple languages as an integrated resource

B. Knowledge emphasised through physical and bodily understanding

C. The imposition of Western educational approaches on other cultures

D. Creating hybrid practices that transcend constituent traditions

E. Memorisation of traditional texts

F. Using diverse participation strategies fluidly

G. Separating students by ability level

H. Teaching only in the local language

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What type of learning is common in many African and Pacific Islander cultures?

38. What two things do teachers need besides knowledge about cultural norms to implement culturally responsive pedagogy effectively?

39. What kind of assessment recognises learning trajectories rather than instantaneous performance?

40. What essential skill for globalised societies do classrooms with integrated participation frameworks help model?

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- C

- B

- C

- D

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- loss of face

- cultural competence

- hybrid participation styles

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- NO

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- NO

- YES

- E

- C

- G

- H

- personal achievement

- knowledge authorities

- bicultural competence

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- B

- C

- C

- C

- C

- B

- A

- D

- F

- apprenticeship-based observational learning

- critical reflexivity (accept: ability to facilitate)

- process-oriented assessment

- intercultural competence

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B – considered evidence of learning

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Western educational systems, active participation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “Verbal contribution is seen as evidence of learning” – đây là paraphrase trực tiếp của đáp án B. Các đáp án khác không được đề cập hoặc mâu thuẫn với thông tin trong bài.

Câu 2: C – social embarrassment and reputation

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: concept of “face”, Asian cultures

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết giải thích “loss of face – a form of social embarrassment that is taken very seriously” – khớp chính xác với đáp án C về sự xấu hổ xã hội và danh tiếng.

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Western teachers, quiet classrooms, disengagement

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: Câu “Teachers in these contexts typically view a quiet classroom as a sign that students are not engaged” khớp chính xác với statement.

Câu 7: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: All Asian students, reluctant to participate

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nhấn mạnh “these are general patterns, and individual students may not conform to cultural stereotypes” – điều này mâu thuẫn với từ “all” trong statement.

Câu 11: loss of face

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: collectivist cultures, making mistakes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Cụm từ “loss of face” xuất hiện ngay sau phần nói về việc mắc lỗi trước mặt người khác trong các nền văn hóa tập thể.

Học sinh đa văn hóa tham gia thảo luận nhóm trong lớp học quốc tế IELTS

Học sinh đa văn hóa tham gia thảo luận nhóm trong lớp học quốc tế IELTS

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: superficial behavioural variations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Tác giả rõ ràng phản đối quan điểm này bằng cách nói “not merely superficial behavioural differences but are rooted in deep psychological frameworks” – trực tiếp mâu thuẫn với statement.

Câu 15: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: brain imaging studies, definitively proven

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn G, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “these findings are preliminary and subject to ongoing research” – điều này mâu thuẫn với từ “definitively proven” trong statement.

Câu 16: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: collectivistic cultures, silence, active form of learning

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn B, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Câu “silence and attentive listening are not passive behaviours but active demonstrations of respect, humility, and commitment to collective learning” khớp chính xác với claim của tác giả.

Câu 20: E

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: meaning conveyed differently, communication

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn E

- Giải thích: Đoạn E thảo luận về high-context và low-context communication styles và cách ý nghĩa được truyền đạt khác nhau qua các văn hóa.

Câu 24: personal achievement

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: individualistic cultures prioritise

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn A, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Cụm “personal achievement” xuất hiện trong danh sách những gì mà các nền văn hóa cá nhân chủ nghĩa ưu tiên.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B – assumes universal applicability despite cultural specificity

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Western educational philosophy, international contexts, problematic

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ trích Western educational theory “positioned itself as universal despite being rooted in specific sociohistorical contexts” – đây là paraphrase của đáp án B.

Câu 28: B – the privileging of linguistic expression as the primary mode of understanding

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: logocentrism

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Định nghĩa được đưa ra: “logocentrism marginalises other modes of knowing” và “privilege linguistic expression as the primary vehicle for thought” – khớp với đáp án B.

Câu 29: C – active engagement in group sense-making processes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: collective cognition, silence during discussion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 6-9

- Giải thích: Bài viết giải thích rằng im lặng “not indicative of non-participation” mà có thể là “actively engaged in collective sense-making processes” – paraphrase chính xác đáp án C.

Câu 32: C – pedagogical imperialism

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: pedagogical imperialism

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Thuật ngữ này được định nghĩa trong ngữ cảnh “pedagogies… are frequently exported to non-Western contexts… with insufficient consideration” – khớp với description C về việc áp đặt phương pháp giáo dục Western.

Câu 37: apprenticeship-based observational learning

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Từ khóa: African and Pacific Islander cultures, type of learning

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: Cụm từ chính xác “apprenticeship-based observational learning common in many African and Pacific Islander cultures” xuất hiện trong bài.

Câu 40: intercultural competence

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Từ khóa: essential skill, globalised societies, classrooms model

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn cuối, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Classrooms that successfully integrate multiple participation frameworks model the intercultural competence increasingly essential in globalised societies” – đây là đáp án chính xác.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| participate | v | /pɑːˈtɪsɪpeɪt/ | tham gia | students participate in classroom activities | actively participate, participate freely |

| cultural background | n | /ˈkʌltʃərəl ˈbækɡraʊnd/ | bối cảnh văn hóa | students from different cultural backgrounds | diverse cultural background |

| critical thinking | n | /ˈkrɪtɪkəl ˈθɪŋkɪŋ/ | tư duy phản biện | educational philosophies that emphasise critical thinking | develop critical thinking |

| verbal contribution | n | /ˈvɜːbəl ˌkɒntrɪˈbjuːʃən/ | đóng góp bằng lời nói | verbal contribution is seen as evidence of learning | make verbal contributions |

| respect for authority | n | /rɪˈspekt fɔːr ɔːˈθɒrəti/ | sự tôn trọng quyền uy | traditional values emphasise respect for authority | show respect for authority |

| collective harmony | n | /kəˈlektɪv ˈhɑːməni/ | sự hòa hợp tập thể | collective harmony over individual expression | maintain collective harmony |

| loss of face | n | /lɒs əv feɪs/ | mất thể diện | making mistakes could result in loss of face | avoid loss of face |

| brainstorming | n | /ˈbreɪnstɔːmɪŋ/ | động não, suy nghĩ sáng tạo | brainstorming is encouraged in Western classrooms | brainstorming session |

| memorisation | n | /ˌmeməraɪˈzeɪʃən/ | sự ghi nhớ, học thuộc | education based on memorisation | rote memorisation |

| multicultural classroom | n | /ˌmʌltiˈkʌltʃərəl ˈklɑːsruːm/ | lớp học đa văn hóa | effective teaching in multicultural classrooms | manage a multicultural classroom |

| inclusive learning environment | n | /ɪnˈkluːsɪv ˈlɜːnɪŋ ɪnˈvaɪrənmənt/ | môi trường học tập hòa nhập | create inclusive learning environments | foster an inclusive learning environment |

| cultural competence | n | /ˈkʌltʃərəl ˈkɒmpɪtəns/ | năng lực văn hóa | develop cultural competence | demonstrate cultural competence |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stark contrast | n | /stɑːk ˈkɒntrɑːst/ | sự tương phản rõ rệt | stark contrasts in classroom participation | stand in stark contrast |

| psychological framework | n | /ˌsaɪkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈfreɪmwɜːk/ | khung tham chiếu tâm lý | rooted in deep psychological frameworks | establish a psychological framework |

| individualistic | adj | /ˌɪndɪˌvɪdʒuəˈlɪstɪk/ | thuộc về chủ nghĩa cá nhân | individualistic cultural orientations | individualistic society |

| collectivistic | adj | /kəˌlektɪˈvɪstɪk/ | thuộc về chủ nghĩa tập thể | collectivistic cultures emphasise group harmony | collectivistic values |

| autonomy | n | /ɔːˈtɒnəmi/ | quyền tự chủ | prioritise personal achievement and autonomy | individual autonomy |

| interdependence | n | /ˌɪntədɪˈpendəns/ | sự phụ thuộc lẫn nhau | emphasise interdependence | social interdependence |

| power distance | n | /ˈpaʊə ˈdɪstəns/ | khoảng cách quyền lực | the power distance dimension | high power distance culture |

| hierarchical structure | n | /ˌhaɪəˈrɑːkɪkəl ˈstrʌktʃə/ | cấu trúc phân cấp | acceptance of hierarchical structures | rigid hierarchical structure |

| egalitarian | adj | /ɪˌɡælɪˈteəriən/ | bình đẳng | favour more egalitarian relationships | egalitarian society |

| high-context culture | n | /haɪ ˈkɒntekst ˈkʌltʃə/ | văn hóa ngữ cảnh cao | high-context cultures rely on implicit communication | typical high-context culture |

| explicit communication | n | /ɪkˈsplɪsɪt kəˌmjuːnɪˈkeɪʃən/ | giao tiếp rõ ràng | favour explicit, direct communication | use explicit communication |

| neuropsychological | adj | /ˌnjʊərəʊˌsaɪkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl/ | thuộc về tâm lý thần kinh | neuropsychological research | neuropsychological studies |

| cognitive processing | n | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˈprəʊsesɪŋ/ | quá trình nhận thức | cultural background may influence cognitive processing | cognitive processing styles |

| culturally responsive pedagogy | n | /ˈkʌltʃərəli rɪˈspɒnsɪv ˈpedəɡɒdʒi/ | phương pháp giảng dạy đáp ứng văn hóa | address challenges through culturally responsive pedagogy | implement culturally responsive pedagogy |

| bicultural competence | n | /baɪˈkʌltʃərəl ˈkɒmpɪtəns/ | năng lực song văn hóa | develop bicultural competence | demonstrate bicultural competence |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proliferation | n | /prəˌlɪfəˈreɪʃən/ | sự gia tăng nhanh chóng | proliferation of multicultural societies | nuclear proliferation |

| monocultural | adj | /ˌmɒnəʊˈkʌltʃərəl/ | đơn văn hóa | monocultural pedagogical frameworks | monocultural environment |

| epistemological | adj | /ɪˌpɪstəməˈlɒdʒɪkəl/ | thuộc về nhận thức luận | radically different epistemological assumptions | epistemological framework |

| paradigm shift | n | /ˈpærədaɪm ʃɪft/ | sự chuyển đổi mô hình | requires a paradigm shift | undergo a paradigm shift |

| hegemonic dominance | n | /ˌheɡɪˈmɒnɪk ˈdɒmɪnəns/ | sự thống trị bá quyền | hegemonic dominance of Western philosophy | establish hegemonic dominance |

| pedagogical imperialism | n | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkəl ɪmˈpɪəriəlɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa đế quốc giáo dục | this pedagogical imperialism | forms of pedagogical imperialism |

| logocentrism | n | /ˌlɒɡəʊˈsentrɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa ngôn ngữ trung tâm | this logocentrism marginalises other modes | Western logocentrism |

| somatic knowledge | n | /səʊˈmætɪk ˈnɒlɪdʒ/ | kiến thức cơ thể | somatic knowledge emphasised in indigenous systems | develop somatic knowledge |

| contemplative understanding | n | /kənˈtemplətɪv ˌʌndəˈstændɪŋ/ | sự hiểu biết chiêm nghiệm | contemplative understanding central to Buddhism | cultivate contemplative understanding |

| collective cognition | n | /kəˈlektɪv kɒɡˈnɪʃən/ | nhận thức tập thể | fails to accommodate collective cognition | theory of collective cognition |

| neurodiversity | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊdaɪˈvɜːsəti/ | sự đa dạng thần kinh | the neurodiversity movement | celebrate neurodiversity |

| third space theory | n | /θɜːd speɪs ˈθɪəri/ | lý thuyết không gian thứ ba | third space theory proposes hybrid practices | apply third space theory |

| translanguaging | n | /trænzˈlæŋɡwɪdʒɪŋ/ | chuyển ngữ | translanguaging theory in multilingual education | translanguaging practices |

| critical reflexivity | n | /ˈkrɪtɪkəl ˌriːflekˈsɪvəti/ | tính phản tư phê phán | teachers need critical reflexivity | develop critical reflexivity |

| affordance | n | /əˈfɔːdəns/ | khả năng hỗ trợ | pedagogical affordances of different approaches | digital affordances |

| intercultural competence | n | /ˌɪntəˈkʌltʃərəl ˈkɒmpɪtəns/ | năng lực liên văn hóa | model intercultural competence | develop intercultural competence |

| ontological compatibility | n | /ˌɒntəˈlɒdʒɪkəl kəmˌpætəˈbɪləti/ | tính tương thích bản thể | ontological compatibility with cultural frameworks | assess ontological compatibility |

| equitable partnership | n | /ˈekwɪtəbəl ˈpɑːtnəʃɪp/ | đối tác công bằng | scholars in equitable partnerships | establish equitable partnerships |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề về ảnh hưởng của văn hóa đến các chiến lược tham gia lớp học không chỉ phản ánh xu hướng toàn cầu hóa giáo dục mà còn là một trong những chủ đề quan trọng thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS Reading. Qua đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được luyện tập với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần, từ cơ bản đến nâng cao, phù hợp với format thi thực tế.

Ba passages đã cung cấp cho bạn góc nhìn toàn diện về vấn đề: từ những khác biệt cơ bản trong cách tham gia lớp học giữa các nền văn hóa, đến những nền tảng tâm lý học sâu xa đằng sau những khác biệt đó, và cuối cùng là những đề xuất về cải cách giáo dục để phù hợp với lớp học đa văn hóa. Mỗi passage không chỉ giúp bạn rèn luyện kỹ năng đọc hiểu mà còn mở rộng kiến thức về một chủ đề xã hội quan trọng.

Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích đã chỉ ra vị trí cụ thể của thông tin trong bài, cách paraphrase giữa câu hỏi và passage, và lý do tại sao các đáp án khác không đúng. Đây là kỹ năng quan trọng giúp bạn tự đánh giá và cải thiện phương pháp làm bài của mình.

Bảng từ vựng với hơn 40 từ và cụm từ quan trọng, kèm phiên âm và collocations, sẽ giúp bạn không chỉ trong phần Reading mà còn trong Writing và Speaking khi gặp các chủ đề liên quan đến giáo dục và văn hóa. Hãy dành thời gian học thuộc và vận dụng những từ vựng này vào bài viết và giao tiếp của bạn.

Để đạt kết quả tốt trong IELTS Reading, hãy nhớ rằng việc luyện tập thường xuyên với các đề thi chất lượng là chìa khóa thành công. Sau khi hoàn thành đề này, hãy xem lại những câu bạn làm sai, hiểu rõ tại sao bạn sai, và rút ra bài học cho lần làm bài tiếp theo. Chúc bạn ôn tập hiệu quả và đạt band điểm như mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!