Mở bài

Chủ đề về cơ sở hạ tầng xe đạp và phát triển đô thị bền vững đang ngày càng trở nên phổ biến trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Đây là một trong những chủ đề thường xuyên xuất hiện trong các bài thi thực tế, đặc biệt từ Cambridge IELTS 14 trở đi, phản ánh xu hướng toàn cầu về môi trường và giao thông xanh.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages theo đúng format thi thật, bao gồm:

- Passage 1 (Easy): Giới thiệu tổng quan về xe đạp và đô thị xanh

- Passage 2 (Medium): Phân tích các yếu tố thiết kế cơ sở hạ tầng xe đạp

- Passage 3 (Hard): Nghiên cứu sâu về tác động kinh tế và xã hội

Mỗi passage đi kèm với câu hỏi đa dạng giống thi thật 100%, đáp án chi tiết có giải thích từng bước, cùng bảng từ vựng quan trọng giúp bạn nâng cao vốn từ học thuật. Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với độ khó tăng dần và rèn luyện kỹ năng quản lý thời gian hiệu quả.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test là bài thi kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, không bị trừ điểm khi sai.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó thấp, câu hỏi trực tiếp)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình, yêu cầu paraphrase)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao, cần suy luận và phân tích)

Lưu ý dành 2-3 phút cuối để chuyển đáp án vào Answer Sheet, tránh mất điểm vì lỗi kỹ thuật.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không đề cập

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi ngắn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Rise of Cycling in Modern Cities

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

In recent decades, cycling has experienced a remarkable renaissance in cities around the world. Once considered merely a recreational activity or a transport option for those who could not afford cars, bicycles are now recognised as a vital component of sustainable urban development. This transformation reflects growing concerns about climate change, traffic congestion, and public health, prompting city planners to reconsider how urban spaces are designed and utilised.

The benefits of cycling are manifold. From an environmental perspective, bicycles produce zero emissions, making them an ideal alternative to motor vehicles in the fight against air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. A single car journey replaced by a bike trip can save approximately 0.9 kilograms of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere. When multiplied across millions of daily journeys, the cumulative impact becomes substantial. Cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam, which have invested heavily in cycling infrastructure, have reported significant reductions in their carbon footprints.

Public health represents another compelling reason for promoting cycling. Regular cycling provides cardiovascular exercise, helps maintain a healthy weight, and reduces the risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers. The World Health Organization recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, and cycling to work or school can easily help individuals meet this target. Studies conducted in the Netherlands, where cycling is deeply embedded in daily life, show that regular cyclists have a mortality rate approximately 30% lower than non-cyclists.

Cơ sở hạ tầng xe đạp trong đô thị bền vững với làn đường riêng biệt và người đi xe đạp

Cơ sở hạ tầng xe đạp trong đô thị bền vững với làn đường riêng biệt và người đi xe đạp

From an economic standpoint, cycling infrastructure offers remarkable value for money. Building a kilometre of bike lane costs a fraction of what is required for road construction or public transport systems. In Portland, Oregon, the entire bicycle network representing hundreds of kilometres of lanes cost less than a single kilometre of urban motorway. Moreover, cyclists contribute significantly to local economies. Research from various cities demonstrates that people who arrive by bicycle tend to make more frequent shopping trips to local businesses compared to those who drive, even if they spend less per visit. Over time, this results in higher overall spending in neighbourhood commercial areas.

Traffic congestion is a growing problem in cities worldwide, costing economies billions in lost productivity and increased fuel consumption. Bicycles require far less space than cars – a single car parking space can accommodate approximately 10 bicycles. Streets designed to accommodate cycling can move more people more efficiently than car-dominated roads. During rush hour in Copenhagen, cyclists outnumber cars in the city centre, and the average journey time by bicycle is often faster than by car or public transport for trips under five kilometres.

However, the success of cycling as a transport mode depends critically on the quality of infrastructure provided. Simply painting bike lanes on existing roads is insufficient. Protected cycling infrastructure – lanes physically separated from motor traffic – has been shown to increase cycling rates dramatically. When New York City installed its first protected bike lanes, cycling increased by over 200% on those routes within the first year. Such infrastructure makes cycling feel safer, which is crucial because perceived safety is the primary factor determining whether people choose to cycle.

The demographic reach of cycling also depends on infrastructure quality. In cities with minimal cycling facilities, cyclists tend to be predominantly young males willing to navigate traffic. In contrast, cities with extensive protected networks see cycling adopted by people of all ages and genders. In the Netherlands, women make slightly more cycle journeys than men, and children as young as eight commonly cycle independently to school – a stark contrast to cities where cycling is perceived as dangerous.

Urban density and mixed-use development complement cycling infrastructure effectively. When homes, workplaces, schools, and shops are located within reasonable cycling distance, bicycles become a practical transport option. Cities designed around the automobile, with sprawling suburbs and separated zones for different activities, make cycling less viable regardless of infrastructure quality. The most successful cycling cities combine dedicated infrastructure with compact urban planning that keeps distances manageable.

Weather is often cited as a barrier to cycling, yet evidence from cities across various climates demonstrates that good infrastructure overcomes this obstacle. Oulu, Finland, maintains high cycling rates despite winter temperatures regularly falling below -20°C, thanks to year-round maintenance of cycle paths, including snow clearance that often exceeds standards for car roads. Similarly, cities in warm climates provide shaded cycle routes and drinking fountains to make summer cycling more comfortable.

The transformation of cities to accommodate cycling represents a significant shift in priorities, moving away from automobile-centric planning that dominated the 20th century. As awareness grows regarding the environmental, health, and economic benefits of cycling, more cities are investing in the infrastructure necessary to make cycling a safe, convenient, and attractive option for residents. This shift not only reduces emissions and improves public health but also creates more liveable urban environments where streets serve people rather than merely facilitating vehicle movement.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

Bicycles were previously viewed mainly as a form of entertainment rather than serious transportation.

-

A car journey produces nearly one kilogram of carbon dioxide emissions when compared to cycling the same distance.

-

The World Health Organization suggests cycling for at least 150 minutes daily.

-

Regular cyclists in the Netherlands have a 30% lower death rate than people who do not cycle.

-

Most cycling infrastructure projects in Europe are funded by private companies.

Questions 6-9

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

Building cycling infrastructure costs much less than constructing roads or __ systems.

-

Although cyclists may spend less per visit, they make more __ trips to local shops than drivers.

-

In Copenhagen during busy periods, the number of __ exceeds the number of cars in the city centre.

-

The main factor that influences people’s decision to cycle is their perception of __.

Questions 10-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, what happened after New York City introduced protected bike lanes?

- A. Car traffic decreased by 200%

- B. Cycling on those routes more than doubled in the first year

- C. Accidents involving cyclists increased

- D. Public transport usage declined

- The passage suggests that in cities with good cycling infrastructure:

- A. Only young people use bicycles

- B. Men cycle more than women

- C. People of all ages and both genders cycle

- D. Children are not allowed to cycle

- According to the passage, what is necessary for cycling to be practical besides good infrastructure?

- A. Cheap bicycles

- B. Government subsidies

- C. Mandatory cycling laws

- D. Compact urban planning with mixed-use development

- The example of Oulu, Finland demonstrates that:

- A. Cold weather prevents cycling

- B. Good infrastructure can overcome weather barriers

- C. Winter cycling is dangerous

- D. Only summer cycling is practical

PASSAGE 2 – Designing Effective Cycling Infrastructure

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The success of cycling as a mainstream transport mode hinges not merely on the presence of cycling facilities, but on their thoughtful design and strategic integration into the broader urban fabric. As cities worldwide seek to reduce their carbon footprints and improve quality of life, understanding the principles of effective cycling infrastructure has become increasingly critical. Research from leading cycling nations reveals that infrastructure quality matters far more than quantity, with poorly designed facilities sometimes discouraging cycling rather than promoting it.

A. Network Connectivity

The fundamental principle of cycling infrastructure is network coherence – creating a comprehensive system where individual routes connect seamlessly to form a citywide network. Fragmented bike lanes that start and stop arbitrarily force cyclists into dangerous situations where they must merge with motor traffic at junctions or navigate gaps in provision. The Dutch concept of “fietssnelwegen” (cycle highways) exemplifies this principle: grade-separated routes that allow cyclists to travel considerable distances without encountering motor traffic or significant delays. These routes connect residential suburbs with employment centres, providing a realistic alternative to driving for commutes of 10-15 kilometres. Studies indicate that network connectivity is the single most important factor influencing cycling rates, with discontinuous networks failing to attract significant numbers of cyclists regardless of the quality of individual segments.

B. Physical Separation

The degree of physical separation between cyclists and motor vehicles represents a critical design decision. Traditional painted bike lanes offer minimal protection and are often encroached upon by parked cars or vehicles making turns. Protected bike lanes, featuring physical barriers such as bollards, planters, or kerbs, create a genuine safety buffer that dramatically increases both actual and perceived safety. Research conducted in multiple cities demonstrates that protected lanes reduce cyclist injury rates by 40-50% compared to painted lanes or shared roadways. The specific type of barrier matters: solid kerbs provide maximum protection but can complicate street maintenance, while flexible bollards offer good protection with easier maintenance access. The optimal choice depends on traffic volumes, vehicle speeds, and available street width.

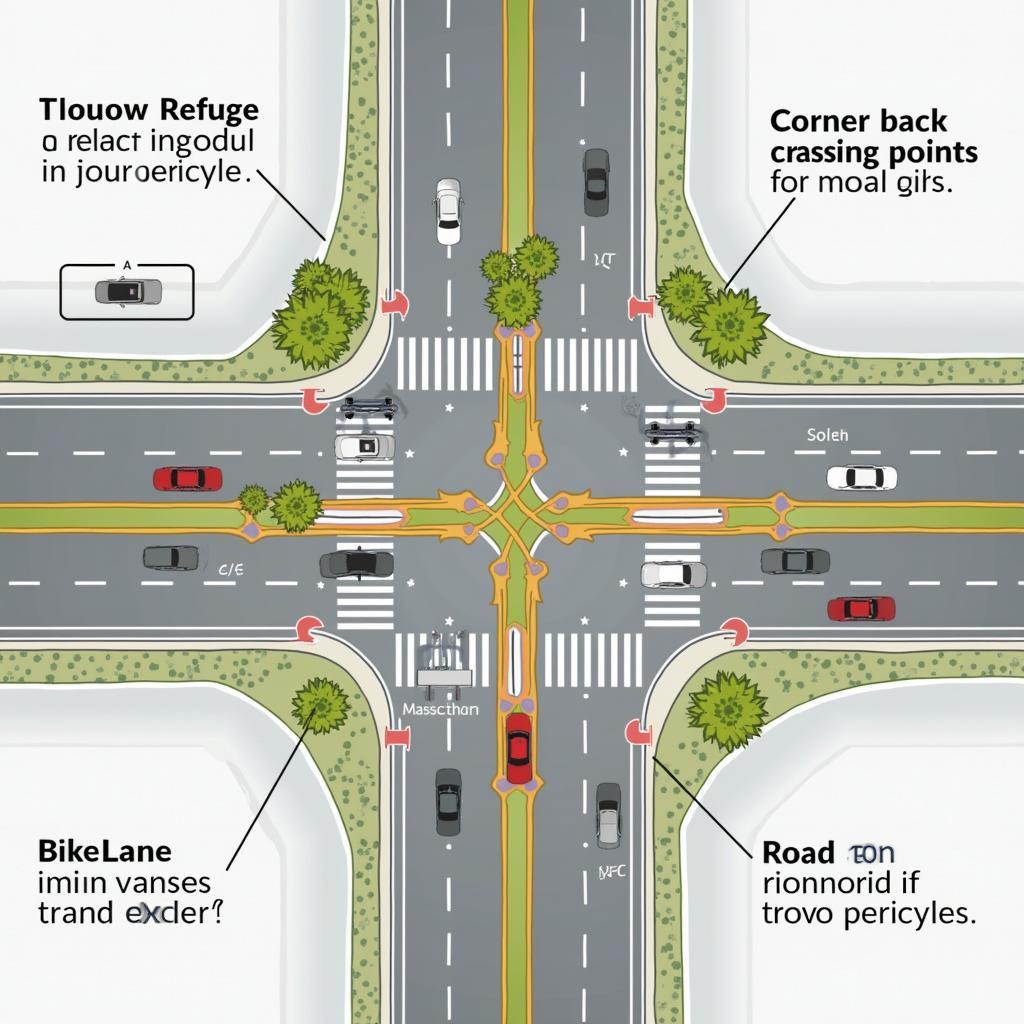

C. Intersection Design

Intersections represent the most dangerous points in cycling networks, accounting for over 60% of serious cyclist casualties in many cities. Conventional intersection design prioritises vehicle throughput, creating conflicts between cyclists and turning vehicles. Advanced cycling cities have developed sophisticated intersection treatments that enhance cyclist safety. Protected intersections, a design pioneered in the Netherlands, use corner refuge islands and setback crossing points to increase visibility between cyclists and drivers, reduce vehicle turning speeds, and provide cyclists with a protected waiting area. Traffic signal timing can be optimised to give cyclists a head start – a “bike box” or advance stop line positions cyclists ahead of motor vehicles at red lights, making them more visible when lights change. Separate signal phases for cyclists, though reducing junction capacity for motor vehicles, virtually eliminate certain conflict types and have proven highly effective in reducing casualties.

Thiết kế ngã tư an toàn cho người đi xe đạp với làn xe riêng biệt và đảo an toàn

Thiết kế ngã tư an toàn cho người đi xe đạp với làn xe riêng biệt và đảo an toàn

D. Surface Quality and Maintenance

The riding surface of cycling infrastructure profoundly affects both comfort and safety. Unlike cars with substantial suspension systems, bicycles are highly sensitive to surface irregularities. Smooth, well-maintained surfaces are essential for attracting a diverse range of cyclists, particularly those using city bikes or cargo bikes. Cobblestones and brick paving, while aesthetically pleasing, create uncomfortable riding conditions and should be reserved for low-speed shared spaces. Asphalt remains the optimal surface material for dedicated cycle paths, offering smoothness, durability, and good drainage characteristics. Maintenance standards for cycling infrastructure should match or exceed those for motor vehicle lanes. In practice, cycle paths often receive inadequate maintenance attention, developing potholes, cracks, and drainage problems that diminish their utility. Winter maintenance proves particularly critical – in cities with successful year-round cycling, snow clearance on major cycle routes often occurs before clearing of secondary roads, recognising that cyclists are more vulnerable to poor surface conditions than motorists.

E. Width and Capacity

Lane width directly influences both safety and capacity. Minimum standards typically specify 1.5 metres for unidirectional paths and 2.5 metres for bidirectional paths, but these dimensions are often inadequate for routes carrying high volumes. In Copenhagen, major commuter routes are 3-4 metres wide to accommodate overtaking and varying cyclist speeds. Cargo bikes, increasingly popular for family transport and deliveries, require additional width. Insufficient width creates conflicts between cyclists of different speeds and abilities, potentially discouraging less confident riders. Peak-hour congestion on popular routes indicates capacity problems that can be addressed through widening, providing parallel routes, or implementing cycling-specific green waves – coordinated traffic signals that allow cyclists maintaining a steady speed to pass through successive intersections without stopping.

F. Wayfinding and Legibility

Effective wayfinding systems are essential for encouraging cycling, particularly among occasional users unfamiliar with optimal routes. Comprehensive signage should indicate distances and journey times to key destinations, recognising that cyclists assess routes differently than motorists. Colour-coded route numbering, successfully implemented in cities like London, helps users navigate complex networks. Smartphone navigation apps increasingly complement physical signage, but cannot replace it entirely as not all cyclists have phone mounts and battery life limitations exist. Surface markings contribute to wayfinding while reinforcing cyclists’ right to space – painted bike symbols, directional arrows, and coloured surfacing at conflict points all enhance legibility. However, excessive reliance on paint without physical protection represents inadequate provision, particularly on high-speed roads.

G. Integration with Other Transport

Cycling infrastructure must integrate effectively with public transport systems to maximise utility. Secure bicycle parking at train and metro stations enables multimodal journeys that extend cycling’s effective range. The Netherlands and Denmark provide extensive covered, secure parking facilities at stations, with some accommodating thousands of bicycles. Bicycle sharing systems, both station-based and free-floating, complement fixed infrastructure by solving the “last kilometre” problem and serving occasional users who lack personal bicycles. Physical infrastructure should accommodate these systems through designated parking zones that don’t obstruct pedestrians or create visual clutter. Bicycle carriage on trains varies widely between systems; generous provision enables longer-distance cycle tourism and recreation while supporting mixed-mode commuting.

The evidence accumulated from decades of experience in leading cycling cities provides clear guidance for effective infrastructure design. Success requires comprehensive networks, high-quality physical infrastructure, priority at intersections, and integration with broader transport systems. While contexts vary and solutions must be adapted to local conditions, the fundamental principles remain consistent. Cities investing in such infrastructure consistently see substantial increases in cycling rates, delivering benefits for public health, environmental quality, and urban liveability that far exceed the relatively modest costs involved.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-19

The passage has seven sections, A-G. Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-G.

-

Information about how different barrier types affect maintenance procedures

-

A description of how digital technology assists cyclists in finding their way

-

Details about the percentage of cyclist injuries that occur at road junctions

-

An explanation of why continuous routes throughout a city are essential

-

Information about bicycle storage facilities at transport hubs

-

Standards for the minimum dimensions of cycling paths

Questions 20-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Effective cycling infrastructure requires more than just adding facilities; it needs proper design and integration. One key principle is creating a (20) __ where different routes connect smoothly across the entire city. Physical separation from motor traffic is crucial, with (21) __ providing much better protection than simple painted lanes. At intersections, which are the most dangerous locations, designs using (22) __ have been developed to improve safety. The riding surface must be smooth and well-maintained, with (23) __ being the best material for dedicated cycling paths.

Questions 24-26

Choose THREE letters, A-G.

Which THREE of the following are mentioned in the passage as features that increase cyclist safety?

A. Smartphone navigation applications

B. Protected intersections with corner refuge islands

C. Bicycle sharing systems

D. Physical barriers separating bikes from motor vehicles

E. Cobblestone paving surfaces

F. Traffic signal timing that gives cyclists a head start

G. Integration with train services

PASSAGE 3 – The Economic and Social Dimensions of Urban Cycling Infrastructure

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The proliferation of cycling infrastructure in contemporary urban environments represents far more than a mere transportation intervention; it constitutes a profound reimagining of urban space that generates complex economic ramifications and social transformations extending well beyond the immediate domain of mobility. While the environmental and health benefits of cycling have been extensively documented and widely publicised, the economic implications and societal impacts remain subject to considerable debate, with recent scholarship revealing both substantial opportunities and potential challenges that demand nuanced consideration by policymakers and urban planners.

From an economic perspective, the return on investment for cycling infrastructure has emerged as remarkably favourable across diverse contexts. Conventional cost-benefit analyses have historically struggled to capture the full value proposition of cycling investments, primarily focusing on narrowly defined transport efficiency metrics while overlooking broader economic multiplier effects. Contemporary research employing more comprehensive methodological frameworks reveals that for every dollar invested in quality cycling infrastructure, cities typically realise returns ranging from three to fourteen dollars through various direct and indirect mechanisms. These returns manifest through multiple channels: reduced healthcare expenditure from increased physical activity levels, decreased road maintenance costs due to lighter vehicle loads, enhanced retail performance in areas with good cycling access, and increased property values adjacent to quality cycling routes.

The retail sector provides particularly compelling evidence of cycling infrastructure’s economic benefits. Contrary to the widespread perception among business proprietors that car parking is essential for commercial viability, empirical studies consistently demonstrate that cyclists constitute highly valuable customers. Research conducted in Toronto’s Bloor Street West district found that while motorists spent more per individual transaction, cyclists visited more frequently, resulting in 2.3 times higher monthly spending at local businesses. This pattern replicates across multiple cities, with studies in Copenhagen, Portland, and Melbourne yielding similar findings. The mechanism operates through several pathways: cyclists travel at speeds conducive to noticing businesses and making spontaneous purchases, face lower barriers to stopping compared to motorists seeking parking, and tend to frequent neighbourhood commercial areas rather than peripheral shopping centres. Moreover, streets with protected cycling infrastructure typically witness increased pedestrian activity through a psychological phenomenon whereby physical separation from motor traffic makes sidewalks feel safer and more pleasant, further enhancing retail environments.

Tác động kinh tế của đường xe đạp đến khu vực thương mại và giá trị bất động sản

Tác động kinh tế của đường xe đạp đến khu vực thương mại và giá trị bất động sản

Property value impacts represent another significant but often overlooked economic dimension. Multiple hedonic pricing studies – which isolate the impact of specific amenities on property values – have identified proximity to quality cycling infrastructure as a positive value factor, with effects ranging from 2% to 11% price premiums depending on context and infrastructure quality. Interestingly, this effect manifests most strongly for protected infrastructure; properties near painted bike lanes show minimal or negative value impacts, likely reflecting the presence of traffic without meaningful safety improvements. The property value effect operates through various mechanisms: enhanced neighbourhood amenity, improved accessibility for residents choosing cycling, and serving as a proxy indicator for progressive urban planning more broadly. This phenomenon carries important implications for municipal finance, as increased property values translate directly to enhanced tax revenue, creating a self-financing mechanism whereby cycling infrastructure investments partially fund themselves through the taxation base expansion they generate.

However, these economic benefits do not accrue uniformly across urban populations, raising significant equity considerations that complicate the straightforward narrative of cycling infrastructure as an unalloyed good. The phenomenon of “bike lane gentrification” has garnered increasing scholarly attention and community concern. Several studies have documented correlations between new cycling infrastructure installation and subsequent neighbourhood gentrification, characterised by rising property values and living costs, demographic transitions toward younger, wealthier, and whiter populations, and displacement of long-term residents. The causal mechanisms remain contested – cycling infrastructure rarely triggers gentrification in isolation but rather functions as one component within broader patterns of urban reinvestment that may include new developments, retail transitions, and enhanced public amenities. Nevertheless, the temporal sequence whereby cycling infrastructure precedes demographic change in some neighbourhoods raises legitimate concerns about whether investments intended as public goods inadvertently accelerate socioeconomic displacement.

This equity challenge is compounded by patterns of infrastructure distribution across urban space. Multiple cities exhibit patterns whereby new cycling infrastructure is concentrated in already affluent, predominantly white neighbourhoods, while lower-income communities of colour receive minimal investment despite potentially benefiting substantially from enhanced transport options and local environmental improvements. This distributive injustice may reflect various factors: political economy considerations favouring areas with more effective advocacy capacity, technical factors such as available street width (which tends to correlate with neighbourhood affluence), and implicit or explicit bias in planning processes. The consequence is that communities most dependent on affordable transportation and most impacted by air pollution – and thus potentially standing to gain most from cycling infrastructure – receive the least investment, while affluent areas already possessing abundant mobility options receive disproportionate resources.

The gendered dimensions of cycling infrastructure constitute another crucial social consideration. Cycling rates typically exhibit stark gender disparities in cities with minimal or low-quality infrastructure, with men outnumbering women by ratios reaching 3:1 or 4:1 in some contexts. This disparity largely dissolves in cities with extensive protected networks; in the Netherlands, women make slightly more cycle trips than men, while Copenhagen approaches gender parity. The mechanism operates through differential safety perceptions – women consistently report higher concerns about traffic safety – and trip purpose differences, with women more commonly making complex trip chains involving child transport and multiple stops that demand higher safety standards. Consequently, cycling infrastructure quality functions as a gendered intervention, with protected networks enabling female mobility in ways that painted lanes or shared roadways fail to achieve. This carries implications beyond individual choice, affecting labour market participation, time allocation, and broader gender equity.

The political economy of cycling infrastructure implementation reveals complex dynamics whereby technical planning considerations intersect with contested urban space and competing mobility paradigms. Cycling infrastructure necessarily reallocates street space, typically reducing capacity for private automobiles or car parking. This reallocation generates opposition from various constituencies: motorist advocacy groups perceiving loss of convenience, business owners fearing reduced accessibility despite contradicting evidence, and sometimes residents concerned about parking availability. These conflicts reflect deeper tensions regarding urban priorities and the legitimate purposes of public space. The framing of cycling infrastructure debates significantly influences outcomes; characterisation as “war on cars” versus “sustainable mobility transition” versus “public health intervention” activates different political coalitions and discursive resources. Cities successfully implementing extensive networks typically employ deliberative processes that acknowledge trade-offs while articulating comprehensive visions of urban futures where enhanced liveability justifies mobility paradigm shifts.

The long-term transformative potential of comprehensive cycling infrastructure extends to fundamental urban form and social organisation. Cities achieving high cycling mode shares witness virtuous cycles whereby increased cyclist presence improves safety through a “safety in numbers” effect, normalises cycling as a transport mode, creates political constituencies supporting further investment, and generates pressures for complementary urban form changes such as mixed-use development and densification. These shifts potentially enable more socially sustainable urban patterns characterised by reduced spatial segregation, enhanced informal social contact through active street life, and more resilient local economies less dependent on automobile access. However, realising this potential requires conscious attention to equity considerations throughout planning and implementation processes, ensuring that cycling infrastructure functions as a tool for inclusive urban development rather than inadvertently accelerating exclusionary gentrification patterns.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, traditional cost-benefit analyses of cycling infrastructure:

- A. Have accurately captured all economic benefits

- B. Focused too narrowly on transportation efficiency

- C. Showed negative returns on investment

- D. Were more comprehensive than modern frameworks

- The research on Bloor Street West in Toronto revealed that:

- A. Motorists spent more money monthly than cyclists

- B. Cyclists spent 2.3 times more per transaction

- C. Cyclists shopped more frequently and spent more overall per month

- D. Car parking was essential for business success

- Properties near painted bike lanes show minimal value increase because:

- A. They are too close to traffic

- B. Painted lanes provide safety without the traffic presence

- C. They indicate traffic presence without meaningful safety benefits

- D. Property buyers don’t value cycling infrastructure

- The term “bike lane gentrification” refers to:

- A. The improvement of cycling infrastructure quality

- B. The correlation between new cycling infrastructure and neighbourhood gentrification

- C. The displacement of cyclists by cars

- D. Investment in wealthy neighbourhoods only

- According to the passage, cycling infrastructure quality functions as a gendered intervention because:

- A. Men prefer cycling more than women

- B. Women have less time to cycle

- C. Protected networks address women’s higher safety concerns and complex trip patterns

- D. Cycling infrastructure is designed only for men

Questions 32-36

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

- Enhanced retail performance in areas with cycling access

- The safety in numbers effect

- Lower-income communities receiving minimal cycling investment

- Differential safety perceptions between genders

- The reallocation of street space from cars to bicycles

A. represents a distributive injustice that denies benefits to those who need them most.

B. generates opposition from motorists and some business owners despite evidence.

C. occurs because of differences in available street width between neighbourhoods.

D. is one of the mechanisms through which cycling infrastructure provides economic returns.

E. improves cycling safety as more people choose to cycle.

F. explains why painted bike lanes are preferred in most cities.

G. largely explains why men cycle more in cities with poor infrastructure.

H. demonstrates that cycling infrastructure should only be built in wealthy areas.

Questions 37-40

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

What type of studies isolate the impact of specific amenities on property values?

-

What range of percentage increase in property values has been identified near quality cycling infrastructure?

-

What do women more commonly make compared to men that requires higher safety standards?

-

What kind of processes do successful cities typically employ when implementing cycling networks?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- public transport

- shopping

- cyclists

- safety

- B

- C

- D

- B

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- B

- F

- C

- A

- G

- E

- citywide network / comprehensive system

- protected bike lanes / protected lanes

- corner refuge islands

- asphalt

- B

- D

- F

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- C

- B

- C

- D

- E

- A

- G

- B

- hedonic pricing studies

- 2% to 11% / two to eleven percent

- complex trip chains

- deliberative processes

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: previously viewed, entertainment, recreational activity

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Passage nói “Once considered merely a recreational activity” – tức là trước đây xe đạp được xem như hoạt động giải trí/vui chơi, khớp với “entertainment” trong câu hỏi. Đây là paraphrase đúng.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: car journey, one kilogram, carbon dioxide

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: Passage viết “A single car journey replaced by a bike trip can save approximately 0.9 kilograms of carbon dioxide” – gần bằng 1kg, câu hỏi dùng “nearly one kilogram” nên là TRUE.

Câu 3: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: World Health Organization, 150 minutes, daily

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: Passage nói “150 minutes… per week” nhưng câu hỏi nói “daily” (mỗi ngày). Đây là mâu thuẫn rõ ràng nên là FALSE.

Câu 4: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Netherlands, regular cyclists, 30% lower, mortality rate

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 7-8

- Giải thích: Passage viết chính xác “regular cyclists have a mortality rate approximately 30% lower than non-cyclists”. Khớp hoàn toàn.

Câu 5: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: cycling infrastructure, Europe, funded, private companies

- Vị trí trong bài: Không có thông tin

- Giải thích: Passage không đề cập đến nguồn tài trợ từ công ty tư nhân hay bất kỳ thông tin nào về funding của các dự án ở châu Âu.

Câu 6: public transport

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: costs much less, constructing roads

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Building a kilometre of bike lane costs a fraction of what is required for road construction or public transport systems.”

Câu 7: shopping

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: spend less per visit, make more trips

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “people who arrive by bicycle tend to make more frequent shopping trips“

Câu 8: cyclists

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: Copenhagen, rush hour, outnumber cars

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 5

- Giải thích: “During rush hour in Copenhagen, cyclists outnumber cars in the city centre”

Câu 9: safety

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: main factor, people’s decision, perception

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “perceived safety is the primary factor determining whether people choose to cycle”

Câu 10: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: New York City, protected bike lanes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “cycling increased by over 200% on those routes within the first year” – tức là tăng gấp đôi (hơn 100% nghĩa là tăng gấp đôi). Đáp án B đúng: “more than doubled”.

Câu 11: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: good cycling infrastructure, demographics

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “cities with extensive protected networks see cycling adopted by people of all ages and genders“. Đáp án C khớp chính xác.

Câu 12: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: besides good infrastructure, practical

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, cả đoạn

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nói về “Urban density and mixed-use development complement cycling infrastructure” và “compact urban planning” – tất cả đều liên quan đến đáp án D.

Câu 13: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Oulu, Finland, demonstrates

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Ví dụ về Oulu cho thấy “good infrastructure overcomes this obstacle” (weather) – tức là cơ sở hạ tầng tốt có thể vượt qua rào cản thời tiết. Đáp án B.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: B (Section B – Physical Separation)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: barrier types, maintenance procedures

- Vị trí trong bài: Section B, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: “solid kerbs provide maximum protection but can complicate street maintenance, while flexible bollards offer good protection with easier maintenance access” – nói về các loại barrier khác nhau ảnh hưởng đến maintenance như thế nào.

Câu 15: F (Section F – Wayfinding and Legibility)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: digital technology, finding their way

- Vị trí trong bài: Section F, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “Smartphone navigation apps increasingly complement physical signage” – đề cập đến công nghệ kỹ thuật số giúp định hướng.

Câu 16: C (Section C – Intersection Design)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: percentage, cyclist injuries, road junctions

- Vị trí trong bài: Section C, dòng 1

- Giải thích: “Intersections represent the most dangerous points… accounting for over 60% of serious cyclist casualties”

Câu 17: A (Section A – Network Connectivity)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: continuous routes, city, essential

- Vị trí trong bài: Section A, toàn bộ

- Giải thích: Section A giải thích về “network coherence” và tầm quan trọng của việc có các tuyến đường liên tục xuyên suốt thành phố.

Câu 18: G (Section G – Integration with Other Transport)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: bicycle storage, transport hubs

- Vị trí trong bài: Section G, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Secure bicycle parking at train and metro stations” – nói về nơi lưu trữ xe đạp tại các trung tâm giao thông.

Câu 19: E (Section E – Width and Capacity)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: minimum dimensions, cycling paths

- Vị trí trong bài: Section E, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Minimum standards typically specify 1.5 metres for unidirectional paths and 2.5 metres for bidirectional paths”

Câu 20: citywide network / comprehensive system

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: routes connect smoothly

- Vị trí trong bài: Section A, dòng 1

- Giải thích: “creating a comprehensive system where individual routes connect seamlessly to form a citywide network“

Câu 21: protected bike lanes / protected lanes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: better protection than painted lanes

- Vị trí trong bài: Section B, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “Protected bike lanes, featuring physical barriers… create a genuine safety buffer”

Câu 22: corner refuge islands

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: designs, improve safety

- Vị trí trong bài: Section C, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “Protected intersections… use corner refuge islands and setback crossing points”

Câu 23: asphalt

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: best material, dedicated cycling paths

- Vị trí trong bài: Section D, dòng 5

- Giải thích: “Asphalt remains the optimal surface material for dedicated cycle paths”

Câu 24-26: B, D, F

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice (chọn 3)

- Giải thích:

- B (Protected intersections with corner refuge islands): Section C nói rõ về protected intersections tăng an toàn

- D (Physical barriers separating bikes from motor vehicles): Section B giải thích về physical separation giảm 40-50% tỷ lệ thương tích

- F (Traffic signal timing that gives cyclists a head start): Section C đề cập “bike box” và advance stop line

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: traditional cost-benefit analyses

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Conventional cost-benefit analyses have historically struggled… primarily focusing on narrowly defined transport efficiency metrics while overlooking broader economic multiplier effects” – tức là tập trung quá hẹp vào hiệu quả giao thông.

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Bloor Street West, Toronto

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “while motorists spent more per individual transaction, cyclists visited more frequently, resulting in 2.3 times higher monthly spending“

Câu 29: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: painted bike lanes, minimal value increase

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “properties near painted bike lanes show minimal or negative value impacts, likely reflecting the presence of traffic without meaningful safety improvements“

Câu 30: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: bike lane gentrification

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “Several studies have documented correlations between new cycling infrastructure installation and subsequent neighbourhood gentrification“

Câu 31: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: gendered intervention

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 5-8

- Giải thích: “The mechanism operates through differential safety perceptions – women consistently report higher concerns about traffic safety – and trip purpose differences, with women more commonly making complex trip chains”

Câu 32: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: Enhanced retail performance được liệt kê như một trong các cơ chế mang lại lợi nhuận kinh tế.

Câu 33: E

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2

- Giải thích: “increased cyclist presence improves safety through a ‘safety in numbers’ effect“

Câu 34: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, toàn đoạn

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn mô tả việc cộng đồng thu nhập thấp không nhận được đầu tư như một “distributive injustice“

Câu 35: G

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 5

- Giải thích: “The mechanism operates through differential safety perceptions” giải thích tại sao nam giới đạp xe nhiều hơn ở những nơi có cơ sở hạ tầng kém.

Câu 36: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “This reallocation generates opposition from various constituencies: motorist advocacy groups… business owners fearing reduced accessibility”

Câu 37: hedonic pricing studies

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short Answer

- Từ khóa: isolate, specific amenities, property values

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2

- Giải thích: “Multiple hedonic pricing studies – which isolate the impact of specific amenities on property values”

Câu 38: 2% to 11% / two to eleven percent

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short Answer

- Từ khóa: range, percentage increase, property values

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3

- Giải thích: “with effects ranging from 2% to 11% price premiums“

Câu 39: complex trip chains

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short Answer

- Từ khóa: women, commonly make, higher safety standards

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “women more commonly making complex trip chains involving child transport and multiple stops that demand higher safety standards”

Câu 40: deliberative processes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short Answer

- Từ khóa: successful cities, employ

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: “Cities successfully implementing extensive networks typically employ deliberative processes“

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| renaissance | n | /ˈrenəsɑːns/ | sự phục hưng, sự tái sinh | cycling has experienced a remarkable renaissance | cultural renaissance, economic renaissance |

| vital component | n phrase | /ˈvaɪtl kəmˈpəʊnənt/ | thành phần thiết yếu | bicycles are now recognised as a vital component | vital component of, essential component |

| manifold | adj | /ˈmænɪfəʊld/ | đa dạng, nhiều mặt | The benefits of cycling are manifold | manifold benefits, manifold advantages |

| cumulative impact | n phrase | /ˈkjuːmjələtɪv ˈɪmpækt/ | tác động tích lũy | the cumulative impact becomes substantial | cumulative impact of, cumulative effect |

| embedded | adj | /ɪmˈbedɪd/ | ăn sâu, gắn bó | cycling is deeply embedded in daily life | deeply embedded, firmly embedded |

| mortality rate | n phrase | /mɔːˈtæləti reɪt/ | tỷ lệ tử vong | have a mortality rate approximately 30% lower | reduce mortality rate, high mortality rate |

| sprawling suburbs | n phrase | /ˈsprɔːlɪŋ ˈsʌbɜːbz/ | vùng ngoại ô lan rộng | Cities with sprawling suburbs | sprawling development, urban sprawl |

| liveable | adj | /ˈlɪvəbl/ | đáng sống | create more liveable urban environments | liveable city, highly liveable |

| traffic congestion | n phrase | /ˈtræfɪk kənˈdʒestʃən/ | tắc nghẽn giao thông | Traffic congestion is a growing problem | reduce traffic congestion, ease congestion |

| automobile-centric | adj | /ˈɔːtəməbiːl ˈsentrɪk/ | lấy ô tô làm trung tâm | moving away from automobile-centric planning | automobile-centric design, car-centric |

| perceived safety | n phrase | /pəˈsiːvd ˈseɪfti/ | sự an toàn cảm nhận | perceived safety is the primary factor | improve perceived safety, perception of safety |

| demographic reach | n phrase | /ˌdeməˈɡræfɪk riːtʃ/ | phạm vi nhân khẩu học | The demographic reach of cycling | expand demographic reach, broader demographic |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strategic integration | n phrase | /strəˈtiːdʒɪk ˌɪntɪˈɡreɪʃn/ | tích hợp chiến lược | strategic integration into the broader urban fabric | strategic integration of, integration strategy |

| network coherence | n phrase | /ˈnetwɜːk kəʊˈhɪərəns/ | tính liên kết mạng lưới | The fundamental principle is network coherence | maintain network coherence, improve coherence |

| fragmented | adj | /fræɡˈmentɪd/ | bị phân mảnh | Fragmented bike lanes force cyclists | fragmented network, highly fragmented |

| grade-separated | adj | /ɡreɪd ˈsepəreɪtɪd/ | tách biệt theo cấp độ | grade-separated routes allow cyclists | grade-separated infrastructure |

| bollards | n | /ˈbɒlədz/ | cột chắn, trụ chắn | physical barriers such as bollards | install bollards, protective bollards |

| encroached upon | v phrase | /ɪnˈkrəʊtʃt əˈpɒn/ | bị xâm lấn | often encroached upon by parked cars | encroach upon space, be encroached |

| casualties | n | /ˈkæʒuəltiz/ | thương vong | accounting for over 60% of serious cyclist casualties | reduce casualties, prevent casualties |

| setback crossing | n phrase | /ˈsetbæk ˈkrɒsɪŋ/ | điểm băng qua lùi vào | use setback crossing points | setback crossing design |

| surface irregularities | n phrase | /ˈsɜːfɪs ɪˌreɡjuˈlærətiz/ | bất thường bề mặt | highly sensitive to surface irregularities | minimize irregularities, surface defects |

| cobblestones | n | /ˈkɒblstəʊnz/ | đá cuội lát đường | Cobblestones create uncomfortable riding | cobblestone streets, historic cobblestones |

| bidirectional | adj | /ˌbaɪdaɪˈrekʃənl/ | hai chiều | 2.5 metres for bidirectional paths | bidirectional lanes, bidirectional flow |

| cargo bikes | n phrase | /ˈkɑːɡəʊ baɪks/ | xe đạp chở hàng | Cargo bikes require additional width | cargo bike delivery, family cargo bikes |

| wayfinding | n | /ˈweɪfaɪndɪŋ/ | định hướng | Effective wayfinding systems are essential | wayfinding signage, wayfinding strategy |

| multimodal journeys | n phrase | /ˌmʌltiˈməʊdl ˈdʒɜːniz/ | hành trình đa phương thức | enable multimodal journeys | multimodal transport, multimodal integration |

| last kilometre | n phrase | /lɑːst ˈkɪləmiːtə/ | cây số cuối cùng | solving the last kilometre problem | first and last kilometre, last mile delivery |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proliferation | n | /prəˌlɪfəˈreɪʃn/ | sự gia tăng nhanh | The proliferation of cycling infrastructure | rapid proliferation, nuclear proliferation |

| profound reimagining | n phrase | /prəˈfaʊnd ˌriːɪˈmædʒɪnɪŋ/ | tái tưởng tượng sâu sắc | represents a profound reimagining of urban space | profound transformation, reimagine urban space |

| ramifications | n | /ˌræmɪfɪˈkeɪʃnz/ | hệ quả, tác động | complex economic ramifications | economic ramifications, far-reaching ramifications |

| multiplier effects | n phrase | /ˈmʌltɪplaɪə ɪˈfekts/ | hiệu ứng nhân | overlooking broader economic multiplier effects | economic multiplier, multiplier effect |

| proprietors | n | /prəˈpraɪətəz/ | chủ sở hữu, chủ doanh nghiệp | perception among business proprietors | business proprietors, property proprietors |

| spontaneous purchases | n phrase | /spɒnˈteɪniəs ˈpɜːtʃəsɪz/ | mua sắm tự phát | making spontaneous purchases | encourage spontaneous purchases |

| hedonic pricing | n phrase | /hiːˈdɒnɪk ˈpraɪsɪŋ/ | định giá hưởng thụ | Multiple hedonic pricing studies | hedonic pricing model, hedonic analysis |

| price premiums | n phrase | /praɪs ˈpriːmiəmz/ | phần giá cao hơn | effects ranging from 2% to 11% price premiums | command price premiums, premium pricing |

| proxy indicator | n phrase | /ˈprɒksi ˈɪndɪkeɪtə/ | chỉ số đại diện | serving as a proxy indicator | proxy indicator for, use as proxy |

| municipal finance | n phrase | /mjuːˈnɪsɪpl ˈfaɪnæns/ | tài chính thành phố | implications for municipal finance | municipal finance system, local finance |

| taxation base | n phrase | /tækˈseɪʃn beɪs/ | cơ sở đánh thuế | taxation base expansion they generate | expand taxation base, tax base |

| unalloyed good | n phrase | /ˌʌnəˈlɔɪd ɡʊd/ | điều tốt thuần khiết | cycling infrastructure as an unalloyed good | unalloyed pleasure, pure good |

| gentrification | n | /ˌdʒentrɪfɪˈkeɪʃn/ | quá trình đô thị hóa cao cấp | bike lane gentrification has garnered attention | urban gentrification, rapid gentrification |

| demographic transitions | n phrase | /ˌdeməˈɡræfɪk trænˈzɪʃnz/ | chuyển đổi nhân khẩu | characterised by demographic transitions | demographic transition, population transition |

| distributive injustice | n phrase | /dɪˈstrɪbjətɪv ɪnˈdʒʌstɪs/ | bất công phân phối | This distributive injustice may reflect | distributive justice, social injustice |

| advocacy capacity | n phrase | /ˈædvəkəsi kəˈpæsəti/ | năng lực vận động | areas with more effective advocacy capacity | advocacy capacity, advocacy groups |

| gender disparities | n phrase | /ˈdʒendə dɪˈspærətiz/ | chênh lệch giới | exhibit stark gender disparities | reduce gender disparities, gender gap |

| gender parity | n phrase | /ˈdʒendə ˈpærəti/ | bình đẳng giới | Copenhagen approaches gender parity | achieve gender parity, gender equality |

| political economy | n phrase | /pəˌlɪtɪkl ɪˈkɒnəmi/ | kinh tế chính trị | The political economy of cycling infrastructure | political economy analysis |

| contested urban space | n phrase | /kənˈtestɪd ˈɜːbən speɪs/ | không gian đô thị tranh chấp | technical planning considerations intersect with contested urban space | contested space, urban contestation |

| deliberative processes | n phrase | /dɪˈlɪbərətɪv ˈprəʊsesɪz/ | quá trình thảo luận | Cities successfully employ deliberative processes | deliberative democracy, deliberative approach |

| virtuous cycles | n phrase | /ˈvɜːtʃuəs ˈsaɪklz/ | chu trình tích cực | Cities witness virtuous cycles | create virtuous cycles, virtuous circle |

| spatial segregation | n phrase | /ˈspeɪʃl ˌseɡrɪˈɡeɪʃn/ | phân tách không gian | reduced spatial segregation | urban spatial segregation, reduce segregation |

Kết bài

Chủ đề về vai trò của cơ sở hạ tầng xe đạp trong các đô thị bền vững không chỉ phổ biến trong IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh những xu hướng toàn cầu về phát triển đô thị xanh và giao thông bền vững. Qua bài thi mẫu này, bạn đã được thực hành với đầy đủ 3 passages theo đúng cấu trúc thi thật, từ độ khó Easy đến Hard.

Passage 1 giới thiệu tổng quan về sự trở lại của xe đạp trong các thành phố hiện đại, với các câu hỏi trực tiếp kiểm tra khả năng xác định thông tin cơ bản. Passage 2 đi sâu vào các yếu tố thiết kế cơ sở hạ tầng xe đạp hiệu quả, yêu cầu kỹ năng paraphrase và hiểu thông tin chi tiết. Passage 3 phân tích chiều sâu về các khía cạnh kinh tế và xã hội, thử thách khả năng suy luận và phân tích ở mức độ cao nhất.

Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích đã chỉ rõ vị trí thông tin trong bài, cách paraphrase giữa câu hỏi và passage, giúp bạn hiểu rõ phương pháp làm bài. Bảng từ vựng tổng hợp hơn 40 từ và cụm từ quan trọng với phiên âm, nghĩa tiếng Việt, ví dụ thực tế và collocations sẽ giúp bạn nâng cao vốn từ học thuật đáng kể.

Hãy luyện tập bài thi này nhiều lần, phân tích kỹ từng câu trả lời sai để rút kinh nghiệm. Đặc biệt chú ý đến kỹ thuật quản lý thời gian: 15-17 phút cho Passage 1, 18-20 phút cho Passage 2, và 23-25 phút cho Passage 3. Việc luyện tập đều đặn với các đề thi chất lượng cao như thế này sẽ giúp bạn tự tin chinh phục band điểm mục tiêu trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading thực tế.