Giới thiệu

Chủ đề về ứng dụng trí tuệ nhân tạo trong dự báo thời tiết đang trở thành một trong những đề tài phổ biến trong IELTS Reading, đặc biệt trong các đề thi gần đây từ năm 2020 trở lại đây. Sự kết hợp giữa công nghệ và khí tượng học không chỉ phản ánh xu hướng phát triển của thời đại mà còn liên quan đến nhiều khía cạnh của đời sống xã hội như nông nghiệp, giao thông và quản lý thiên tai.

Bài viết này cung cấp một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages từ mức độ dễ đến khó, giúp bạn làm quen với:

- Đề thi đầy đủ 3 passages theo đúng cấu trúc thực tế (Easy → Medium → Hard)

- 40 câu hỏi đa dạng với 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading

- Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí và cách paraphrase

- Từ vựng quan trọng được phân loại theo từng passage với phiên âm và ví dụ

- Kỹ thuật làm bài và phân bổ thời gian hiệu quả

Bộ đề này phù hợp cho học viên có mục tiêu từ band 5.0 trở lên, đặc biệt hữu ích cho những ai đang luyện tập để đạt band 6.5-7.5.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được 1 điểm và không bị trừ điểm khi sai. Độ khó tăng dần từ Passage 1 đến Passage 3, do đó việc phân bổ thời gian hợp lý là vô cùng quan trọng.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó thấp, nên làm nhanh để dành thời gian cho passage sau)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình, cần đọc kỹ hơn)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao nhất, yêu cầu phân tích sâu)

Lưu ý dành 2-3 phút cuối để chuyển đáp án vào Answer Sheet và kiểm tra lại.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Bộ đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không có trong bài

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

Mỗi dạng câu hỏi yêu cầu kỹ năng đọc hiểu khác nhau, từ scanning (quét thông tin) đến skimming (đọc lướt) và detailed reading (đọc chi tiết).

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Evolution of Weather Forecasting

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Weather forecasting has come a long way since ancient civilisations attempted to predict the weather by observing natural phenomena. The Babylonians, as early as 650 BC, tried to forecast weather based on cloud patterns, while the ancient Greeks relied on astronomical observations. However, these early methods were largely inaccurate and based more on superstition than science.

The scientific approach to weather prediction began in the 17th century when instruments such as the thermometer and barometer were invented. These tools allowed meteorologists to measure atmospheric pressure and temperature with precision. In 1854, the first weather map was created, marking a significant milestone in the field. By plotting data from various locations, scientists could begin to understand weather patterns and their movements across regions.

The 20th century witnessed revolutionary changes in meteorology. The invention of the telegraph enabled rapid communication of weather data between stations, while radar technology, developed during World War II, allowed meteorologists to track precipitation and storm systems in real time. The launch of the first weather satellite in 1960 provided a bird’s-eye view of Earth’s atmosphere, transforming our ability to monitor weather on a global scale.

Computer technology brought another quantum leap in forecasting capabilities. In the 1950s, scientists began using numerical weather prediction (NWP), which involves solving complex mathematical equations that describe atmospheric behaviour. Early computers could take an entire day to produce a 24-hour forecast, but as processing power increased, forecasts became faster and more reliable.

Modern weather forecasting relies on sophisticated computer models that process vast amounts of data from multiple sources. Weather stations on land and sea, aircraft observations, weather balloons, and satellites all contribute information about temperature, humidity, wind speed, and pressure. These data points are fed into supercomputers that run simulation models to predict future weather conditions.

Despite these advances, weather forecasting still faces limitations. The atmosphere is a chaotic system, meaning small changes in initial conditions can lead to dramatically different outcomes – a concept known as the “butterfly effect.” This inherent unpredictability means that forecast accuracy decreases the further into the future we try to predict. Current models can provide reasonably accurate forecasts for up to seven days, but predictions beyond two weeks remain highly uncertain.

Regional variations also present challenges. Mountainous terrain, coastal areas, and urban environments all create localised weather patterns that are difficult to model accurately. Additionally, extreme weather events like hurricanes and tornadoes remain particularly challenging to predict with precision, though forecasters have become much better at identifying the conditions that make them likely.

The impact of improved forecasting on society cannot be overstated. Accurate weather predictions help farmers plan planting and harvesting, allow airlines to route flights more efficiently, and enable emergency services to prepare for severe weather. Lives are saved when communities receive advance warning of dangerous conditions, and economic losses are reduced when businesses can plan around weather disruptions.

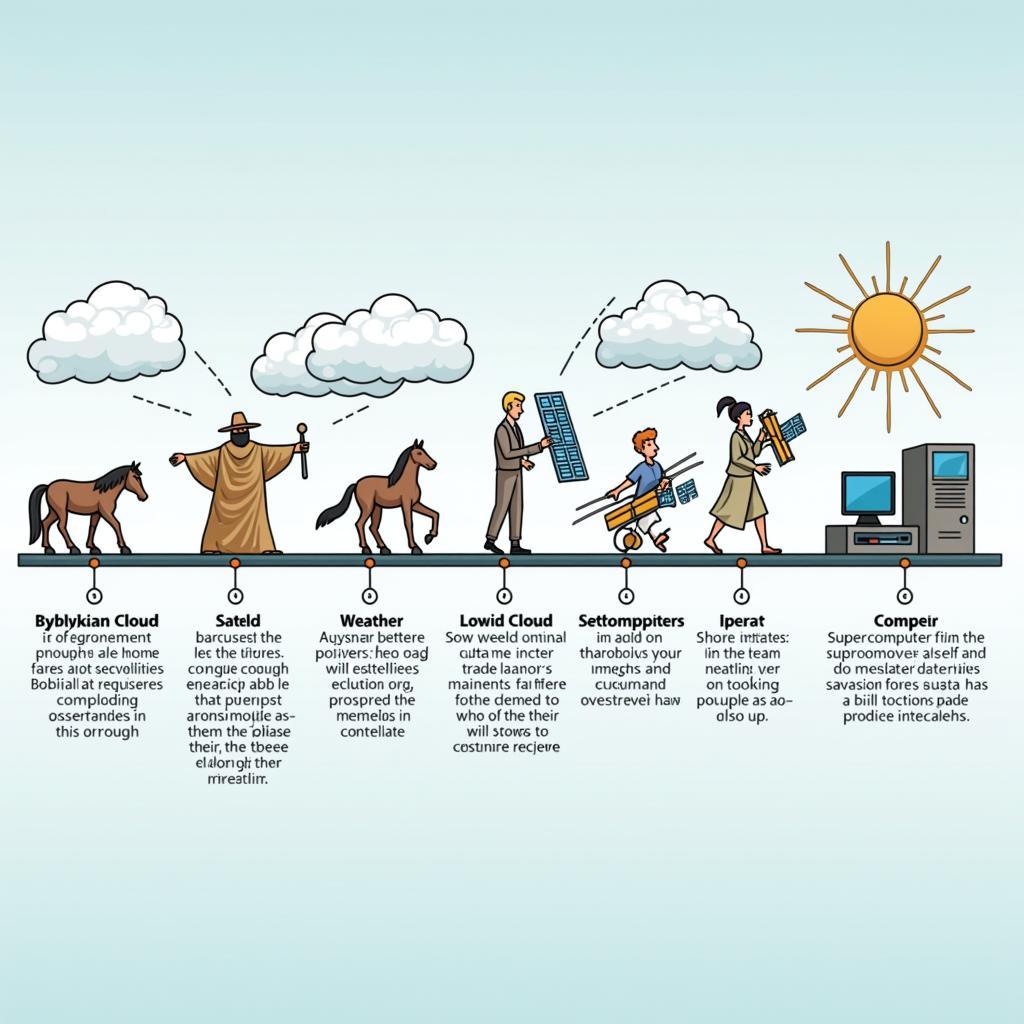

Sự tiến hóa của dự báo thời tiết từ phương pháp cổ đại đến hiện đại trong IELTS Reading

Sự tiến hóa của dự báo thời tiết từ phương pháp cổ đại đến hiện đại trong IELTS Reading

Questions 1-6

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the reading passage?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- Ancient Greek weather predictions were based primarily on watching cloud formations.

- The first weather map was produced in the mid-19th century.

- Weather satellites were launched before radar technology was invented.

- Early computer forecasting models could produce predictions faster than modern systems.

- The butterfly effect explains why long-term weather forecasts are less accurate.

- Hurricane predictions have shown no improvement over the past decades.

Questions 7-10

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- The invention of the __ allowed weather data to be shared quickly between different locations.

- Computer-based weather prediction uses __ to describe how the atmosphere behaves.

- Modern forecasting systems collect information from various sources including aircraft and __.

- Weather forecasting is particularly difficult in areas with __, coastal regions, and cities.

Questions 11-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, what was the main problem with ancient weather forecasting methods?

- A. They relied on expensive equipment

- B. They were based more on belief than science

- C. They could only predict short-term weather

- D. They required too many people to operate

-

What does the passage suggest about current weather forecasting capabilities?

- A. They can accurately predict weather for months ahead

- B. They are most reliable for predictions within one week

- C. They work better in urban areas than rural ones

- D. They have eliminated all uncertainty from forecasts

-

The main purpose of this passage is to:

- A. Explain how weather satellites function

- B. Criticise the limitations of modern forecasting

- C. Describe the historical development of weather prediction

- D. Compare different forecasting methods used today

PASSAGE 2 – Artificial Intelligence Transforms Meteorology

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into weather forecasting represents a paradigm shift in meteorological science. While traditional numerical weather prediction models have served the field well for decades, they are increasingly being augmented or even replaced by machine learning algorithms that can process data and identify patterns in ways that were previously impossible.

Conventional forecasting models work by dividing the atmosphere into a three-dimensional grid and solving physics-based equations for each grid point. This approach, while scientifically rigorous, has inherent limitations. The equations are so complex that approximations must be made, and the computational resources required are enormous. Even the world’s most powerful supercomputers struggle to model the atmosphere at the resolution needed to capture all important weather phenomena. Smaller-scale features like localised thunderstorms or microclimates often slip through the gaps.

This is where AI excels. Rather than solving equations, machine learning models learn to recognise patterns from historical weather data. They are trained on decades of observations and the outcomes of previous weather events, enabling them to identify subtle correlations that might elude traditional methods. Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, employs artificial neural networks – systems loosely inspired by the human brain – that can process multiple layers of information simultaneously.

One particularly promising application is the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), originally developed for image recognition. Weather data, when visualised as maps or satellite images, shares many characteristics with other types of images. CNNs can analyse these patterns to predict how weather systems will evolve. In 2020, researchers at Google demonstrated that their AI model could make accurate rainfall predictions up to six hours in advance, outperforming traditional methods for short-term forecasting.

DeepMind, another leader in AI research, has developed models that can predict precipitation with remarkable accuracy in the near term. Their nowcasting system, which focuses on predictions within the next two hours, has proven particularly valuable for applications where immediate warnings are crucial, such as aviation and emergency management. The system’s ability to rapidly process satellite imagery and radar data allows it to detect developing storms before conventional systems register them as threats. The interdisciplinary collaboration between meteorologists and AI experts at the University of Wisconsin has demonstrated comparable advantages in predicting extreme weather events.

Ensemble forecasting – running multiple simulations with slightly different starting conditions to assess uncertainty – has also been enhanced by AI. Machine learning can optimise which variations to test and how to weight the different outcomes, making ensemble predictions more informative and computationally efficient. This addresses one of the fundamental challenges in meteorology: the atmosphere’s chaotic nature means that small measurement errors or approximations can lead to widely diverging predictions.

However, the adoption of AI in meteorology is not without controversy. Sceptics point out that machine learning models are essentially “black boxes” – they can produce predictions, but understanding why they make specific forecasts is difficult. Traditional models, despite their limitations, are based on physical laws that scientists understand. If an AI model predicts an unprecedented weather event, meteorologists may hesitate to trust it without understanding the underlying reasoning.

Data quality presents another challenge. Machine learning models are only as good as the data they’re trained on. Historical weather records contain biases and gaps, particularly for certain regions and time periods. If training data is unrepresentative, the model may make erroneous predictions when confronted with novel situations. Climate change adds another layer of complexity: as weather patterns shift, historical data may become less relevant for predicting future conditions.

Computational demands also remain significant. While AI models can be more efficient than traditional physics-based simulations in some respects, training deep learning systems requires substantial processing power and energy. The environmental footprint of running massive neural networks has raised ethical questions about the sustainability of AI-driven forecasting.

Despite these concerns, the trajectory is clear: AI and traditional meteorology are becoming increasingly intertwined. Many operational weather services now use hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both methods. Physics-based models provide the foundational understanding and long-range predictions, while AI enhances short-term accuracy and helps identify localised phenomena. This synergy may represent the future of weather forecasting – not AI replacing meteorologists, but working alongside them to provide more precise, timely, and actionable weather information.

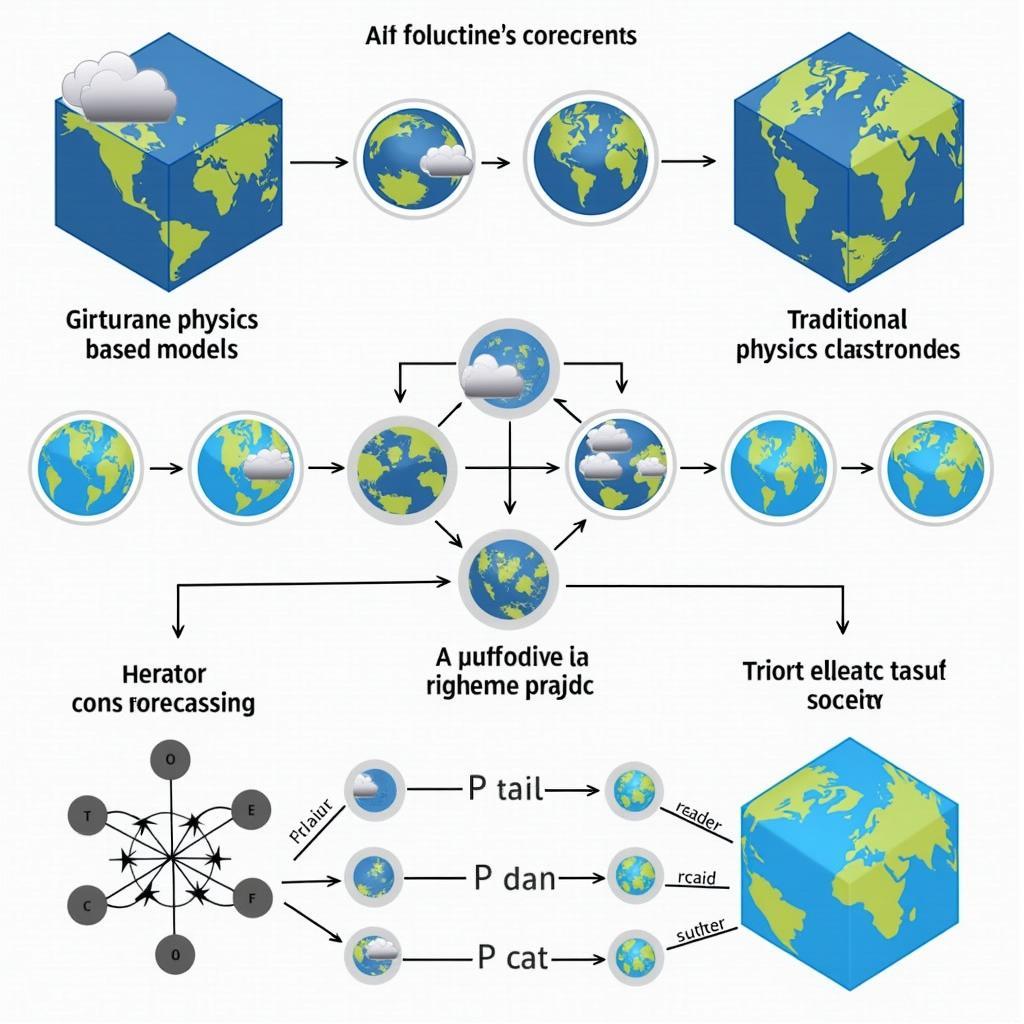

Ứng dụng trí tuệ nhân tạo và machine learning trong dự báo thời tiết hiện đại

Ứng dụng trí tuệ nhân tạo và machine learning trong dự báo thời tiết hiện đại

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

What is the main limitation of traditional numerical weather prediction models mentioned in paragraph 2?

- A. They are too expensive to operate

- B. They cannot process historical data

- C. They require simplifications due to complexity

- D. They work only in specific geographic areas

-

According to the passage, convolutional neural networks are particularly suitable for weather forecasting because:

- A. They were specifically designed for meteorological applications

- B. Weather data can be treated similarly to image data

- C. They require less computational power than other methods

- D. They are easier to understand than traditional models

-

The DeepMind nowcasting system is especially useful for:

- A. Long-term climate predictions

- B. Understanding historical weather patterns

- C. Situations requiring immediate weather warnings

- D. Reducing the cost of weather forecasting

-

Why do some meteorologists hesitate to fully trust AI predictions?

- A. AI models are too expensive to implement

- B. The reasoning behind AI forecasts is not transparent

- C. AI cannot process satellite data effectively

- D. AI models require too much training time

-

The author’s view on the future of weather forecasting is that:

- A. AI will completely replace traditional methods

- B. Traditional methods will prove superior to AI

- C. Both approaches will work together complementarily

- D. Neither approach is adequate for accurate forecasting

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-L, below.

Artificial intelligence is changing weather forecasting by using 19 __ to identify patterns in historical data. Unlike traditional methods that solve mathematical equations, AI models can recognise 20 __ that conventional approaches might miss. One advantage is their ability to enhance 21 __, which involves running multiple simulations to measure uncertainty. However, AI faces challenges including its “black box” nature and concerns about 22 __. Despite these issues, most experts believe the future involves 23 __ that combine both AI and traditional meteorology.

A. machine learning

B. data quality

C. hybrid approaches

D. subtle correlations

E. computational costs

F. ensemble forecasting

G. weather satellites

H. physical laws

I. temperature changes

J. grid systems

K. radar technology

L. climate patterns

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in the reading passage?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Machine learning models are always more accurate than physics-based forecasting models.

- Climate change may reduce the usefulness of historical weather data for training AI systems.

- The energy consumption of AI weather forecasting systems is lower than traditional methods.

PASSAGE 3 – The Future Landscape of AI-Enhanced Weather Prediction

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The confluence of exponentially increasing computational power, burgeoning datasets, and sophisticated algorithmic innovations is catalysing a transformation in atmospheric science that extends far beyond mere incremental improvements in forecast accuracy. This metamorphosis encompasses not only the methodological underpinnings of weather prediction but also the epistemological frameworks through which we understand and interact with meteorological phenomena. As we navigate this unprecedented juncture, it becomes imperative to examine both the transformative potential and the profound implications of AI-augmented forecasting systems for science, society, and the intricate relationship between humanity and the natural world.

Contemporary AI architectures employed in meteorology increasingly leverage generative adversarial networks (GANs) and transformer models, technologies that have revolutionised fields as diverse as natural language processing and genomic analysis. GANs, which consist of two neural networks engaged in an adversarial process – one generating predictions and the other evaluating their plausibility – have demonstrated remarkable capability in producing high-resolution weather simulations. These models can effectively “hallucinate” detailed weather patterns at scales finer than the input data resolution, a process called super-resolution that addresses one of the most persistent challenges in meteorology: the trade-off between spatial resolution and computational feasibility.

Transformer architectures, originally developed for processing sequential language data, have found unexpected applicability in temporal weather prediction. These models excel at identifying long-range dependencies in data sequences – precisely the capability needed to understand how atmospheric conditions at one point in time influence weather days or weeks later. Research published in Nature has shown that transformer-based models can capture teleconnections – relationships between weather patterns in geographically disparate regions – with unprecedented fidelity. For instance, they can learn how El Niño conditions in the Pacific Ocean correlate with precipitation patterns in distant continents, relationships that emerge from the data itself rather than being explicitly programmed based on theoretical understanding.

The integration of AI into weather forecasting also facilitates entirely new approaches to data assimilation – the process of combining observations with model predictions to produce optimal initial conditions for forecasts. Traditional data assimilation techniques, such as four-dimensional variational methods (4D-Var) and ensemble Kalman filters, are mathematically elegant but computationally intensive. Machine learning offers the possibility of approximating these methods more efficiently or even developing entirely new assimilation frameworks that can handle heterogeneous data sources more effectively. The proliferation of non-traditional observations – from smartphone barometric pressure sensors to crowdsourced weather reports and Internet-of-Things devices – generates vast amounts of potentially valuable but irregular and variable-quality data that conventional systems struggle to incorporate. AI excels at extracting meaningful signals from such noisy, unstructured datasets.

Probabilistic forecasting represents another domain where AI is making substantial contributions. Rather than providing a single prediction, probabilistic forecasts offer a distribution of possible outcomes with associated likelihoods, giving users richer information for decision-making. Bayesian deep learning techniques can quantify uncertainty more comprehensively than traditional ensemble methods, distinguishing between aleatory uncertainty (inherent randomness in atmospheric processes) and epistemic uncertainty (limitations in model knowledge). This nuanced understanding of uncertainty is invaluable for risk-sensitive applications such as renewable energy management, where operators must balance the intermittency of solar and wind resources against grid stability requirements, as explored in recent studies on technological innovations in renewable energy systems.

The operationalisation of AI in meteorology extends to specialised forecasting domains where traditional models have struggled. Hydrological forecasting – predicting river flows, flood risks, and water availability – benefits from machine learning’s ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships between precipitation, soil moisture, topography, and runoff. Given that climate change is intensifying the water cycle and creating more extreme hydrological events, improved predictions in this realm have profound implications for water resource management and disaster preparedness. Research examining what are the effects of climate change on water availability? highlights these escalating challenges.

Air quality forecasting constitutes another critical application. Pollutant dispersion depends on intricate interactions between weather conditions, emission sources, and chemical reactions. Machine learning models can assimilate data from dense sensor networks and satellite observations to predict pollution levels with granularity and accuracy that benefit public health interventions. During wildfire season, AI systems can forecast smoke dispersion patterns, enabling authorities to issue targeted health advisories and make informed decisions about evacuations or outdoor activity restrictions.

However, the ascendance of AI in meteorology raises substantive concerns that extend beyond technical challenges. The concentration of cutting-edge capabilities in well-resourced institutions and commercial entities risks exacerbating global inequalities in access to weather information. Developing nations, which are often most vulnerable to weather-related disasters, may lack the infrastructure and expertise to deploy advanced AI systems, creating a “forecasting divide”. International cooperation and technology transfer become ethically imperative to ensure that AI’s benefits are equitably distributed.

The interpretability challenge assumes particular gravity in contexts where forecasts inform life-or-death decisions. When an AI model predicts a catastrophic event – a category 5 hurricane, an extreme flooding event, or a devastating heatwave – meteorologists and emergency managers must weigh whether to initiate costly and disruptive protective measures. If the model’s reasoning is opaque, this decision becomes fraught with difficulty. Recent advances in explainable AI (XAI) offer some promise, developing techniques that can elucidate which input features most influenced a particular prediction. However, translating these technical explanations into intuitive understanding that supports operational decision-making remains an active area of research.

Climate change introduces a fundamental epistemic challenge: AI models trained on historical data may be ill-equipped to predict weather in a climate regime that increasingly deviates from past conditions. The statistical distributions of weather variables are shifting – extreme events are becoming more frequent, seasonal patterns are changing, and novel combinations of conditions may emerge. This non-stationarity threatens to undermine the very foundation of data-driven prediction. Hybrid approaches that embed physical understanding within machine learning architectures – often called physics-informed neural networks – represent one strategy for addressing this challenge, ensuring that models respect fundamental conservation laws even when extrapolating beyond their training data.

The relationship between weather forecasting and climate prediction further complicates the picture, particularly as these domains increasingly intersect with infrastructure resilience, as seen in what are the challenges of integrating renewable energy into national grids? and how renewable energy is transforming the mining industry. Weather forecasts focus on specific conditions days or weeks ahead, while climate projections describe statistical characteristics of weather over decades or centuries. AI is blurring these boundaries, enabling subseasonal-to-seasonal (S2S) forecasts that bridge the gap between traditional weather and climate timescales. These intermediate-range predictions are particularly valuable for agriculture, water management, and disaster preparedness, sectors that operate on timescales where conventional forecasts offer limited guidance.

Looking forward, the trajectory of AI in meteorology suggests a future where weather prediction becomes increasingly personalised, granular, and integrated into decision-support systems. Rather than generic forecasts broadcast to wide areas, AI could enable hyperlocal predictions tailored to individual users’ needs and locations. Autonomous systems – from self-driving vehicles to agricultural drones – will require real-time weather intelligence to operate safely and efficiently. The synergy between advances in weather prediction and disaster management technologies, as discussed in role of technology in disaster management, will amplify these benefits across multiple sectors.

Yet this future also demands vigilance about unintended consequences. As society becomes more dependent on AI-generated forecasts, the ramifications of model failures grow more severe. Cybersecurity vulnerabilities in forecasting infrastructure could be exploited with catastrophic results. The environmental cost of the computational resources required for AI – both in energy consumption and electronic waste – must be weighed against the benefits. And the displacement of human expertise as AI assumes more forecasting responsibilities raises questions about maintaining the scientific understanding necessary to critically evaluate and improve these systems.

The evolution of weather forecasting through AI thus represents a microcosm of broader questions facing humanity in an age of increasingly powerful and pervasive artificial intelligence: How do we harness transformative capabilities while mitigating risks? How do we ensure equitable access to technological benefits? How do we maintain human agency and understanding in domains increasingly mediated by algorithmic decision-making? The answers we develop in meteorology may offer instructive lessons for other fields grappling with similar challenges, making the stakes of getting this transition right extend far beyond weather prediction alone.

Tương lai của dự báo thời tiết với công nghệ AI tiên tiến và ứng dụng đa ngành

Tương lai của dự báo thời tiết với công nghệ AI tiên tiến và ứng dụng đa ngành

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, generative adversarial networks (GANs) in weather forecasting are particularly useful for:

- A. Processing natural language data

- B. Creating detailed predictions at finer scales than input data

- C. Reducing the cost of supercomputer operations

- D. Eliminating the need for satellite observations

-

What does the passage suggest about transformer architectures in meteorology?

- A. They were originally designed specifically for weather applications

- B. They cannot identify relationships between distant regions

- C. They can learn connections that weren’t explicitly programmed

- D. They are less effective than traditional forecasting methods

-

The main advantage of Bayesian deep learning in weather forecasting is:

- A. It eliminates all uncertainty from predictions

- B. It distinguishes between different types of uncertainty

- C. It requires less computational power than other methods

- D. It can predict weather patterns decades in advance

-

According to the passage, the “forecasting divide” refers to:

- A. Disagreements between meteorologists about AI effectiveness

- B. The gap between short-term and long-term forecasting accuracy

- C. Unequal access to advanced weather forecasting technology

- D. Differences between weather and climate prediction methods

-

The author’s attitude toward physics-informed neural networks can best be described as:

- A. Highly critical

- B. Cautiously optimistic

- C. Completely dismissive

- D. Unreservedly enthusiastic

Questions 32-36

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

- Data assimilation using AI

- Probabilistic forecasting

- AI models trained on historical data

- Explainable AI techniques

- Subseasonal-to-seasonal forecasts

A. may struggle to predict weather in changing climate conditions.

B. can help meteorologists understand why AI made specific predictions.

C. eliminates the need for human meteorologists entirely.

D. can handle irregular data from diverse sources more effectively.

E. provides a range of possible outcomes with probability estimates.

F. works only in tropical climate regions.

G. bridge the gap between weather forecasts and climate projections.

H. requires no computational resources to operate.

Questions 37-40

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

What type of uncertainty represents inherent randomness in atmospheric processes rather than limitations in model knowledge?

-

Which two application domains are mentioned as benefiting from machine learning’s ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships?

-

What term describes the problem that weather variable distributions are changing as climate patterns shift?

-

What kind of forecasts does the passage suggest AI could enable instead of generic forecasts broadcast to wide areas?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- telegraph

- mathematical equations

- weather balloons

- mountainous terrain

- B

- B

- C

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- C

- B

- C

- B

- C

- A

- D

- F

- B

- C

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- B

- C

- B

- D

- E

- A

- B

- G

- aleatory uncertainty

- hydrological forecasting (and) air quality forecasting

- non-stationarity

- hyperlocal predictions / personalised predictions

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Ancient Greek, weather predictions, cloud formations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Câu hỏi nói người Hy Lạp cổ đại dự đoán thời tiết chủ yếu dựa vào hình dạng mây (cloud formations), nhưng trong bài viết: “the ancient Greeks relied on astronomical observations” – người Hy Lạp dựa vào quan sát thiên văn, còn người Babylon mới dựa vào hình dạng mây. Đây là thông tin mâu thuẫn nên đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: first weather map, mid-19th century

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “In 1854, the first weather map was created” – năm 1854 thuộc giữa thế kỷ 19 (mid-19th century), khớp hoàn toàn với thông tin trong câu hỏi.

Câu 3: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Weather satellites, launched before, radar technology

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “radar technology, developed during World War II” (khoảng 1940s), sau đó “The launch of the first weather satellite in 1960” – vệ tinh được phát triển SAU radar, không phải trước. Đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 4: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Early computer forecasting, faster than modern systems

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “Early computers could take an entire day to produce a 24-hour forecast, but as processing power increased, forecasts became faster” – máy tính sớm MẤT CẢ NGÀY để tạo dự báo 24 giờ, sau đó mới nhanh hơn. Câu hỏi nói máy tính sớm nhanh hơn hiện đại là SAI.

Câu 5: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: butterfly effect, long-term forecasts, less accurate

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “small changes in initial conditions can lead to dramatically different outcomes – a concept known as the ‘butterfly effect.’ This inherent unpredictability means that forecast accuracy decreases the further into the future we try to predict” – hiệu ứng cánh bướm giải thích tại sao dự báo dài hạn kém chính xác hơn.

Câu 7: telegraph

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: invention, allowed weather data, shared quickly

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “The invention of the telegraph enabled rapid communication of weather data between stations” – phát minh telegraph cho phép chia sẻ dữ liệu nhanh chóng.

Câu 11: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: ancient weather forecasting, main problem

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “these early methods were largely inaccurate and based more on superstition than science” – các phương pháp cổ đại dựa nhiều vào mê tín hơn là khoa học (belief/superstition hơn là science).

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: limitation, traditional numerical weather prediction

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “The equations are so complex that approximations must be made” – các phương trình quá phức tạp nên phải đơn giản hóa (simplifications/approximations). Đây là hạn chế chính được nhắc đến.

Câu 15: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: convolutional neural networks, suitable for weather forecasting

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Weather data, when visualised as maps or satellite images, shares many characteristics with other types of images. CNNs can analyse these patterns” – dữ liệu thời tiết có thể được xử lý như dữ liệu hình ảnh, đó là lý do CNNs phù hợp.

Câu 18: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: author’s view, future of weather forecasting

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn cuối, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: “Many operational weather services now use hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both methods… AI working alongside them” – tác giả cho rằng tương lai là sự kết hợp của cả hai phương pháp (complementarily).

Câu 19-23: Summary Completion

- Câu 19: A (machine learning) – “machine learning algorithms that can process data”

- Câu 20: D (subtle correlations) – “identify subtle correlations that might elude traditional methods”

- Câu 21: F (ensemble forecasting) – “Ensemble forecasting… has also been enhanced by AI”

- Câu 22: B (data quality) – “Data quality presents another challenge”

- Câu 23: C (hybrid approaches) – “Many operational weather services now use hybrid approaches”

Câu 25: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Climate change, reduce usefulness, historical data

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “Climate change adds another layer of complexity: as weather patterns shift, historical data may become less relevant for predicting future conditions” – biến đổi khí hậu làm dữ liệu lịch sử ít phù hợp hơn, khớp với tuyên bố của tác giả.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: GANs, particularly useful

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “These models can effectively ‘hallucinate’ detailed weather patterns at scales finer than the input data resolution, a process called super-resolution” – GANs tạo ra các mô phỏng chi tiết ở quy mô nhỏ hơn dữ liệu đầu vào (finer scales).

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: transformer architectures, suggest

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “relationships that emerge from the data itself rather than being explicitly programmed based on theoretical understanding” – các mối liên hệ nổi lên TỰ NHIÊN từ dữ liệu chứ không được lập trình trực tiếp.

Câu 30: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: “forecasting divide”

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Developing nations… may lack the infrastructure and expertise to deploy advanced AI systems, creating a ‘forecasting divide'” – sự phân chia dự báo là do các nước đang phát triển không có khả năng triển khai công nghệ AI tiên tiến (unequal access).

Câu 32-36: Matching Sentence Endings

- Câu 32: D – “AI… can handle heterogeneous data sources more effectively”

- Câu 33: E – “probabilistic forecasts offer a distribution of possible outcomes with associated likelihoods”

- Câu 34: A – “AI models trained on historical data may be ill-equipped to predict weather in a climate regime that increasingly deviates from past conditions”

- Câu 35: B – “explainable AI… developing techniques that can elucidate which input features most influenced a particular prediction”

- Câu 36: G – “subseasonal-to-seasonal (S2S) forecasts that bridge the gap between traditional weather and climate timescales”

Câu 37: aleatory uncertainty

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: uncertainty, inherent randomness, atmospheric processes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “distinguishing between aleatory uncertainty (inherent randomness in atmospheric processes) and epistemic uncertainty” – aleatory uncertainty là loại đại diện cho sự ngẫu nhiên vốn có.

Câu 38: hydrological forecasting (and) air quality forecasting

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions (cần 2 cụm từ)

- Từ khóa: application domains, complex nonlinear relationships

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6 và 7

- Giải thích: Đoạn 6 nói “Hydrological forecasting… benefits from machine learning’s ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships” và đoạn 7 nói về “Air quality forecasting” với các mối quan hệ phức tạp tương tự.

Câu 40: hyperlocal predictions / personalised predictions

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: AI could enable, instead of generic forecasts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 12, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Rather than generic forecasts broadcast to wide areas, AI could enable hyperlocal predictions tailored to individual users’ needs” – AI có thể tạo ra dự báo siêu địa phương hoặc cá nhân hóa thay vì dự báo chung chung.

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| predict | v | /prɪˈdɪkt/ | Dự đoán, dự báo | predict the weather | weather prediction, accurately predict |

| atmospheric pressure | n | /ˌætməsˈferɪk ˈpreʃər/ | Áp suất khí quyển | measure atmospheric pressure | high/low atmospheric pressure |

| milestone | n | /ˈmaɪlstəʊn/ | Cột mốc quan trọng | significant milestone | major milestone, achieve a milestone |

| radar technology | n | /ˈreɪdɑː tekˈnɒlədʒi/ | Công nghệ radar | radar technology allowed meteorologists to track | advanced radar technology |

| track precipitation | v phrase | /træk prɪˌsɪpɪˈteɪʃən/ | Theo dõi lượng mưa | track precipitation and storm systems | accurately track |

| quantum leap | n | /ˈkwɒntəm liːp/ | Bước nhảy vọt | quantum leap in forecasting | make a quantum leap |

| numerical weather prediction | n | /njuːˈmerɪkəl ˈweðə prɪˈdɪkʃən/ | Dự báo thời tiết số trị | using numerical weather prediction | NWP model |

| sophisticated | adj | /səˈfɪstɪkeɪtɪd/ | Tinh vi, phức tạp | sophisticated computer models | highly sophisticated |

| supercomputer | n | /ˈsuːpəkəmpjuːtə/ | Siêu máy tính | data are fed into supercomputers | powerful supercomputer |

| chaotic system | n | /keɪˈɒtɪk ˈsɪstəm/ | Hệ thống hỗn loạn | The atmosphere is a chaotic system | complex chaotic system |

| butterfly effect | n | /ˈbʌtəflaɪ ɪˈfekt/ | Hiệu ứng cánh bướm | a concept known as the butterfly effect | demonstrate butterfly effect |

| localised | adj | /ˈləʊkəlaɪzd/ | Có tính địa phương | create localised weather patterns | highly localised |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paradigm shift | n | /ˈpærədaɪm ʃɪft/ | Sự thay đổi mô hình tư duy | represents a paradigm shift | major paradigm shift |

| augment | v | /ɔːɡˈment/ | Bổ sung, tăng cường | being augmented or replaced | augment capabilities |

| resolution | n | /ˌrezəˈluːʃən/ | Độ phân giải | at the resolution needed | high/low resolution |

| convolutional neural network | n | /ˌkɒnvəˈluːʃənəl ˈnjʊərəl ˈnetwɜːk/ | Mạng thần kinh tích chập | use of convolutional neural networks | train a CNN |

| outperform | v | /ˌaʊtpəˈfɔːm/ | Vượt trội hơn | outperforming traditional methods | significantly outperform |

| nowcasting | n | /ˈnaʊkɑːstɪŋ/ | Dự báo thời tiết ngắn hạn | Their nowcasting system | nowcasting accuracy |

| precipitation | n | /prɪˌsɪpɪˈteɪʃən/ | Lượng mưa, giáng thủy | predict precipitation | heavy precipitation |

| ensemble forecasting | n | /ɒnˈsɒmbl ˈfɔːkɑːstɪŋ/ | Dự báo tập hợp | Ensemble forecasting has been enhanced | ensemble prediction system |

| black box | n | /blæk bɒks/ | Hộp đen (không thể hiểu rõ cơ chế bên trong) | models are essentially black boxes | treat as a black box |

| unprecedented | adj | /ʌnˈpresɪdentɪd/ | Chưa từng có | an unprecedented weather event | unprecedented scale |

| erroneous | adj | /ɪˈrəʊniəs/ | Sai lầm | make erroneous predictions | erroneous conclusion |

| trajectory | n | /trəˈdʒektəri/ | Quỹ đạo, xu hướng phát triển | the trajectory is clear | career trajectory |

| intertwined | adj | /ˌɪntəˈtwaɪnd/ | Đan xen, liên kết chặt chẽ | becoming increasingly intertwined | closely intertwined |

| hybrid approach | n | /ˈhaɪbrɪd əˈprəʊtʃ/ | Phương pháp kết hợp | use hybrid approaches | adopt a hybrid approach |

| synergy | n | /ˈsɪnədʒi/ | Sự hiệp đồng | This synergy may represent | create synergy |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| confluence | n | /ˈkɒnfluəns/ | Sự hội tụ | The confluence of computational power | confluence of factors | |

| burgeoning | adj | /ˈbɜːdʒənɪŋ/ | Đang phát triển mạnh | burgeoning datasets | burgeoning industry | |

| catalyse | v | /ˈkætəlaɪz/ | Xúc tác, thúc đẩy | is catalysing a transformation | catalyse change | |

| metamorphosis | n | /ˌmetəˈmɔːfəsɪs/ | Sự biến đổi hoàn toàn | This metamorphosis encompasses | undergo metamorphosis | |

| epistemological | adj | /ɪˌpɪstɪməˈlɒdʒɪkəl/ | Thuộc nhận thức luận | the epistemological frameworks | epistemological approach | |

| generative adversarial network | n | /ˈdʒenərətɪv ædˈvɜːsəriəl ˈnetwɜːk/ | Mạng đối nghịch sinh | leverage generative adversarial networks | train a GAN | |

| plausibility | n | /ˌplɔːzəˈbɪləti/ | Tính hợp lý | evaluating their plausibility | assess plausibility | |

| super-resolution | n | /ˈsuːpə ˌrezəˈluːʃən/ | Siêu phân giải | a process called super-resolution | super-resolution technique | |

| teleconnection | n | /ˌtelikəˈnekʃən/ | Liên kết từ xa (hiện tượng khí hậu) | can capture teleconnections | atmospheric teleconnection | |

| data assimilation | n | /ˈdeɪtə əˌsɪmɪˈleɪʃən/ | Đồng hóa dữ liệu | new approaches to data assimilation | data assimilation system | |

| heterogeneous | adj | /ˌhetərəˈdʒiːniəs/ | Không đồng nhất | handle heterogeneous data sources | heterogeneous mixture | |

| probabilistic forecasting | n | /ˌprɒbəbɪˈlɪstɪk ˈfɔːkɑːstɪŋ/ | Dự báo xác suất | Probabilistic forecasting represents | probabilistic approach | |

| aleatory uncertainty | n | /ˈeɪliətəri ʌnˈsɜːtənti/ | Độ không chắc chắn ngẫu nhiên | aleatory uncertainty (inherent randomness) | quantify aleatory uncertainty | |

| epistemic uncertainty | n | /ˌepɪˈstiːmɪk ʌnˈsɜːtənti/ | Độ không chắc chắn nhận thức | epistemic uncertainty (limitations in knowledge) | reduce epistemic uncertainty | |

| operationalisation | n | /ˌɒpərəʃənəlaɪˈzeɪʃən/ | Sự vận hành hóa | The operationalisation of AI | operationalisation process | |

| hydrological | adj | /ˌhaɪdrəˈlɒdʒɪkəl/ | Thuộc thủy văn | Hydrological forecasting | hydrological cycle | |

| exacerbate | v | /ɪɡˈzæsəbeɪt/ | Làm trầm trọng thêm | risks exacerbating global inequalities | exacerbate the problem | |

| interpretability | n | /ɪnˌtɜːprɪtəˈbɪləti/ | Tính có thể giải thích được | The interpretability challenge | improve interpretability | |

| non-stationarity | n | /ˌnɒn ˌsteɪʃəˈnærəti/ | Tính không dừng (thống kê) | This non-stationarity threatens | address non-stationarity | |

| extrapolate | v | /ɪkˈstræpəleɪt/ | Ngoại suy | when extrapolating beyond training data | extrapolate from data | |

| ramifications | n | /ˌræmɪfɪˈkeɪʃənz/ | Hệ quả, ảnh hưởng | the ramifications of model failures | serious ramifications | |

| pervasive | adj | /pəˈveɪsɪv/ | Lan tỏa, phổ biến rộng rãi | increasingly pervasive artificial intelligence | pervasive influence | |

| harness | v | /ˈhɑːnɪs/ | Khai thác, tận dụng | How do we harness transformative capabilities | harness technology | |

| mitigate | v | /ˈmɪtɪɡeɪt/ | Giảm thiểu | while mitigating risks | mitigate the impact |

Kết bài

Chủ đề về ứng dụng trí tuệ nhân tạo trong dự báo thời tiết không chỉ phản ánh xu hướng công nghệ hiện đại mà còn liên quan mật thiết đến nhiều lĩnh vực khác như quản lý thiên tai, năng lượng tái tạo và nông nghiệp. Việc nắm vững chủ đề này giúp bạn chuẩn bị tốt cho các đề thi IELTS Reading có nội dung về công nghệ và môi trường.

Bộ đề thi mẫu này đã cung cấp đầy đủ ba passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, giúp bạn trải nghiệm cấu trúc thực tế của IELTS Reading Test. Với 40 câu hỏi đa dạng bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất, bạn có cơ hội luyện tập toàn diện các kỹ năng đọc hiểu cần thiết.

Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin và cách paraphrase sẽ giúp bạn tự đánh giá năng lực và hiểu rõ những điểm còn cần cải thiện. Đặc biệt, phần từ vựng được tổng hợp theo từng passage với phiên âm, nghĩa và ví dụ sẽ giúp bạn xây dựng vốn từ vựng học thuật một cách có hệ thống.

Để đạt hiệu quả cao nhất, hãy làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật (60 phút, không tra từ điển), sau đó đối chiếu đáp án và phân tích kỹ những câu sai. Đừng quên ghi chép và ôn tập thường xuyên các từ vựng mới để nâng cao khả năng đọc hiểu của mình. Chúc bạn luyện tập hiệu quả và đạt được band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS!