Mở Bài

Chủ đề về ảnh hưởng của mạng xã hội đối với hoạt động chính trị

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh gồm 3 passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như thi thật. Bạn sẽ được thực hành với các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Yes/No/Not Given, Matching Headings, và nhiều dạng khác. Sau mỗi passage, bạn sẽ có đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích rõ ràng, giúp bạn hiểu cách xác định đáp án đúng và phân tích kỹ thuật paraphrase trong IELTS Reading.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, đặc biệt hữu ích cho những bạn đang mục tiêu band 6.5-7.5. Hãy dành 60 phút để hoàn thành bài test này trong điều kiện giống thi thật, sau đó đối chiếu đáp án và học từ vựng quan trọng được tổng hợp ở cuối bài.

1. Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút và bao gồm 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Điểm đặc biệt là bạn không có thời gian chuyển đáp án sang answer sheet riêng như IELTS Listening, vì vậy phải quản lý thời gian rất chặt chẽ.

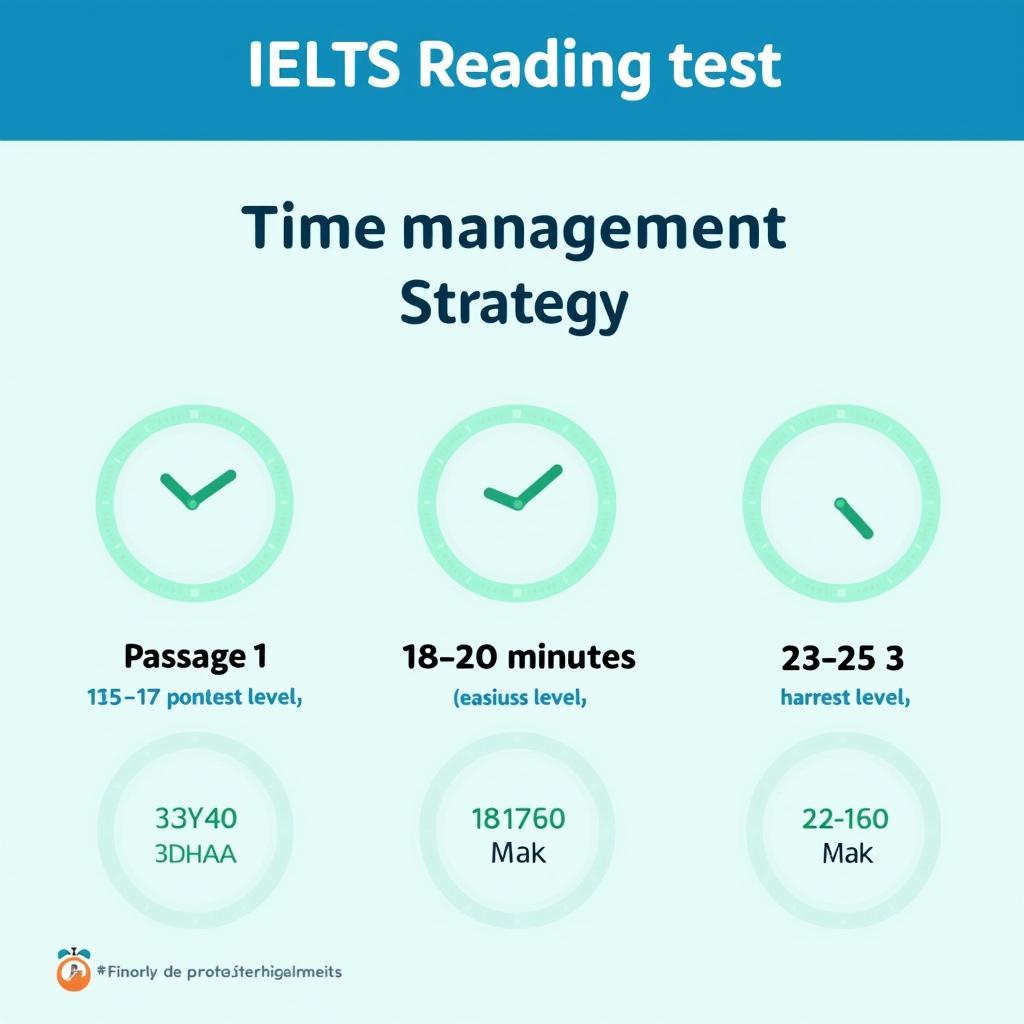

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó thấp nhất)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao nhất)

Lưu ý: Nếu một câu hỏi quá khó, hãy đánh dấu và tiếp tục, quay lại sau nếu còn thời gian. Đừng để một câu khó chiếm mất quá nhiều thời gian quý báu của bạn.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Chọn đáp án đúng từ A, B, C, D

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hay không được đề cập

- Yes/No/Not Given – Xác định quan điểm tác giả đồng ý, không đồng ý hay không đề cập

- Matching Headings – Ghép tiêu đề phù hợp với đoạn văn

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu với từ trong bài

- Matching Features – Ghép thông tin với các đối tượng được liệt kê

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi bằng từ trong bài

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Rise of Digital Activism

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Over the past two decades, social media platforms have fundamentally transformed how people engage in political activism. Traditional forms of protest, such as street demonstrations and petition signing, have been complemented—and in some cases replaced—by online campaigns that can reach millions of people within hours. This shift has created both opportunities and challenges for those seeking social change.

The most obvious advantage of social media activism is its ability to mobilize large numbers of people quickly and efficiently. When a political issue gains traction online, it can spread virally across networks, reaching audiences that traditional media might never access. For example, the hashtag campaigns that emerged during various social movements in the 2010s demonstrated how a simple phrase could unite people across different countries and cultures. Activists no longer need substantial financial resources or connections to mainstream media to make their voices heard. A single individual with a smartphone can now broadcast their message to a global audience.

Social media platforms also provide tools for organizing collective action. Event pages, group chats, and live streaming capabilities allow activists to coordinate protests, share real-time updates, and document incidents as they happen. This immediate documentation has proven particularly valuable in holding authorities accountable, as videos and photographs can be shared instantly before they can be suppressed. The transparency afforded by these technologies has made it more difficult for governments to hide human rights abuses or respond to protests without public scrutiny.

However, the relationship between social media and political activism is not entirely positive. Critics argue that online activism, sometimes dismissively called “clicktivism” or “slacktivism,” can create an illusion of participation without generating meaningful change. Liking a post or sharing a hashtag requires minimal effort and commitment compared to attending a physical protest or engaging in sustained organizing work. Some researchers suggest that this low-barrier participation might actually reduce the likelihood that individuals will take more substantive action, as they feel they have already done their part by engaging online.

Another significant concern is the role of social media algorithms in shaping political discourse. These algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement, which often means promoting content that generates strong emotional reactions. This can lead to the amplification of extreme viewpoints and the creation of echo chambers where users are primarily exposed to information that confirms their existing beliefs. Rather than fostering productive dialogue across different perspectives, social media can sometimes deepen political polarization.

Misinformation presents another major challenge for digital activism. The same features that allow activists to spread their message quickly can also enable the rapid dissemination of false or misleading information. Fake news stories, manipulated images, and coordinated disinformation campaigns can muddy public understanding of issues and undermine legitimate activist efforts. The speed at which information travels on social media often outpaces the ability of fact-checkers to verify claims, meaning false narratives can become widely accepted before corrections are made.

Despite these challenges, there is evidence that social media activism can translate into real-world impact. Several studies have shown that online campaigns can influence public opinion, pressure corporations to change policies, and even contribute to electoral outcomes. The key factor appears to be whether online activity is connected to offline organizing. When social media is used as one tool among many—complementing rather than replacing traditional activism—it can significantly enhance the effectiveness of social movements.

Looking forward, the relationship between social media and political activism will likely continue to evolve as platforms change their policies and new technologies emerge. Activists are becoming more sophisticated in their use of these tools, developing strategies to combat misinformation, break through algorithmic filters, and convert online support into tangible action. Meanwhile, governments and corporations are also adapting, sometimes using the same platforms to surveil activists or spread their own messages.

The question is no longer whether social media affects political activism, but rather how activists can best harness its potential while mitigating its risks. Success in the digital age requires media literacy, critical thinking, and a recognition that online tools are most powerful when integrated into broader strategies for social change. As technology continues to advance, the challenge for activists will be staying ahead of those who seek to manipulate these platforms for less democratic purposes.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

1. According to the passage, social media activism differs from traditional activism primarily in its:

A. effectiveness in achieving goals

B. speed and reach of communication

C. requirement for financial resources

D. ability to create social change

2. The author mentions hashtag campaigns to illustrate:

A. the limitations of online activism

B. the global nature of social media

C. how simple tools can unite people internationally

D. the need for traditional media support

3. What does the passage suggest about “clicktivism”?

A. It is more effective than traditional activism

B. It requires significant personal commitment

C. It may reduce more substantial forms of participation

D. It has replaced physical protests entirely

4. Social media algorithms are criticized in the passage for:

A. being too complicated for average users

B. promoting extreme views and creating echo chambers

C. preventing activists from organizing effectively

D. blocking political content automatically

5. According to the passage, social media activism is most effective when:

A. used exclusively without offline activities

B. focused solely on viral campaigns

C. combined with traditional organizing methods

D. avoiding mainstream media attention

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

6. Social media has completely replaced traditional forms of political protest.

7. Live streaming capabilities help activists document events in real-time.

8. Most social media companies actively support political activism.

9. Misinformation on social media spreads faster than fact-checkers can verify claims.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

10. Critics sometimes use the term “____” to describe online activism that requires little effort.

11. Social media algorithms are designed to maximize ____ rather than promote balanced information.

12. Governments and corporations may use social media platforms to ____ activists.

13. Success in digital activism requires ____ and the ability to think critically about information.

PASSAGE 2 – The Psychological Impact of Online Political Engagement

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The proliferation of social media has not only changed the mechanics of political activism but has also profoundly affected the psychological experience of political engagement. Researchers studying digital activism have identified several ways in which online platforms alter how individuals perceive, process, and respond to political information, with implications that extend far beyond the immediate goal of any particular campaign or movement.

One significant psychological effect is what scholars call “moral outrage fatigue.” Social media users are exposed to a constant stream of information about injustices, conflicts, and crises occurring around the world. While this heightened awareness can initially spur action, the relentless barrage of distressing content can eventually lead to emotional exhaustion and desensitization. Studies have shown that individuals who spend significant time consuming political content on social media report higher levels of stress, anxiety, and feelings of helplessness. This phenomenon creates a paradox: the very tools designed to facilitate engagement may actually contribute to political apathy over time.

The architecture of social media platforms also influences how people experience political disagreement. The asynchronous nature of online communication—where responses can be delayed and carefully crafted—differs fundamentally from face-to-face dialogue. While this can allow for more thoughtful responses, it can also reduce the social cues and empathy that typically moderate in-person disagreements. Research indicates that people are more likely to express extreme opinions and engage in hostile behavior online than they would in physical settings, a phenomenon known as the “online disinhibition effect.” This can transform political discussions into adversarial encounters rather than opportunities for mutual understanding.

However, social media can also foster positive psychological experiences related to political participation. For individuals who feel marginalized or isolated in their immediate communities, online platforms can provide access to like-minded individuals and supportive networks. This sense of collective identity can be empowering, particularly for members of minority groups who might otherwise struggle to find others who share their political concerns. The validation and encouragement received through online interactions can strengthen political self-efficacy—the belief that one’s actions can make a difference—which is a crucial predictor of sustained activism.

The gamification elements present in many social media platforms introduce another psychological dimension to political engagement. Likes, shares, retweets, and follower counts create quantifiable metrics of impact and popularity. While these metrics can provide immediate feedback and motivation, they can also lead to what psychologists call “performative activism“—engaging in political behavior primarily to enhance one’s social image rather than out of genuine commitment to a cause. The desire for social validation may drive individuals to share content that generates the most reaction, which is not always the most accurate or constructive information.

Furthermore, the reward mechanisms built into social media platforms can create addictive patterns of behavior. The intermittent reinforcement provided by notifications and engagement metrics activates the brain’s dopamine system in ways similar to gambling. This can lead users to compulsively check their feeds and notifications, interrupting other activities and contributing to what researchers term “continuous partial attention“—a state where individuals are constantly monitoring their devices while struggling to focus deeply on any single task. For activists, this can undermine the sustained concentration required for strategic planning and in-depth analysis of complex political issues.

The phenomenon of “context collapse” on social media adds yet another layer of psychological complexity. In physical spaces, people naturally adjust their behavior and communication style based on their audience—speaking differently to family members than to colleagues, for instance. On social media, however, diverse audiences coexist in the same space. A political post might be viewed by family members, co-workers, old friends, and strangers simultaneously. This flattening of social contexts can create anxiety about how messages will be interpreted and can lead individuals to either self-censor or present idealized versions of their political beliefs that may not reflect their true views.

Cognitive biases are amplified in social media environments, affecting how individuals process political information. Confirmation bias—the tendency to seek out and favor information that confirms existing beliefs—is particularly pronounced in algorithm-driven feeds that prioritize content similar to what users have previously engaged with. The availability heuristic, where people judge the frequency of events based on how easily examples come to mind, can be distorted by the non-representative sample of information presented in social media feeds. Dramatic or emotional stories that go viral may create misperceptions about the prevalence of certain issues, leading activists to misallocate their efforts or adopt strategies based on incomplete understanding of problems.

Despite these psychological challenges, research suggests that mindful engagement with social media can mitigate many negative effects. Deliberate practices such as limiting exposure to distressing content, curating feeds to include diverse perspectives, taking regular digital detoxes, and maintaining offline social connections can help individuals navigate the psychological demands of online activism. Media literacy education that helps users understand how platforms function and how to critically evaluate information is increasingly recognized as essential for healthy political engagement in the digital age.

The psychological impact of social media activism ultimately depends on how individuals and communities choose to use these tools. When approached strategically and with awareness of potential pitfalls, digital platforms can enhance political participation and create meaningful connections. However, without this awareness, the same tools can contribute to burnout, polarization, and superficial engagement that undermines the very goals activists seek to achieve. Understanding these psychological dynamics is essential for anyone seeking to leverage social media effectively for political change while maintaining their mental well-being.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in the passage?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

14. Constant exposure to political content on social media inevitably leads to increased activism.

15. Online communication lacks some of the social cues that help moderate face-to-face disagreements.

16. Social media platforms intentionally design features to make users addicted to political content.

17. Quantifiable metrics like likes and shares always improve the quality of political activism.

18. Mindful engagement with social media can reduce some of its negative psychological effects.

Questions 19-22: Matching Headings

Choose the correct heading for sections i-iv from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

- A. The role of reward systems in online behavior

- B. Financial benefits of social media activism

- C. How algorithms promote balanced political views

- D. The challenge of managing multiple audiences

- E. Positive effects of online political communities

- F. The decline of traditional media influence

- G. Emotional exhaustion from constant political information

- H. Strategies for effective offline organizing

19. Section discussing moral outrage fatigue (Paragraph 2)

20. Section discussing marginalized individuals finding support (Paragraph 4)

21. Section discussing likes, shares, and follower counts (Paragraph 5)

22. Section discussing context collapse (Paragraph 7)

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Social media affects political engagement psychologically in various ways. The constant stream of distressing content can lead to 23. ____ and emotional exhaustion. Additionally, the 24. ____ built into platforms can create addictive behaviors similar to gambling. Users may also experience 25. ____, a state where they constantly monitor devices without focusing deeply. Meanwhile, 26. ____ are amplified in social media environments, affecting how people process political information.

PASSAGE 3 – Algorithmic Governance and the Future of Digital Political Discourse

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The ascendancy of social media platforms as primary conduits for political information and activism has precipitated a fundamental shift in how democratic discourse is structured and mediated. Unlike traditional mass media, where editorial gatekeepers determined which information reached the public, contemporary digital platforms employ sophisticated algorithms that curate content based on complex calculations of user behavior, engagement patterns, and commercial imperatives. This algorithmic mediation of political content raises profound questions about autonomy, manipulation, and the infrastructure of democratic participation in the digital age.

The opacity of content recommendation algorithms constitutes one of the most significant challenges to understanding their impact on political activism. These algorithms, often considered proprietary trade secrets, function as black boxes whose internal logic remains inscrutable to outside observers. While platforms may provide general explanations of how their systems work—typically emphasizing user preferences and engagement metrics—the precise parameters and weighting systems that determine which content appears in any given user’s feed are closely guarded. This lack of transparency makes it exceedingly difficult for activists, researchers, or regulators to assess whether these systems are inadvertently or intentionally shaping political discourse in ways that serve corporate interests rather than democratic values.

Empirical research into algorithmic amplification has revealed troubling patterns. Several studies have demonstrated that content eliciting strong emotional reactions—particularly anger and moral indignation—receives preferential treatment in recommendation systems because such content generates higher engagement rates. This structural bias toward emotionally provocative material has significant implications for political activism. Nuanced arguments, carefully reasoned positions, and calls for compromise are systematically disadvantaged compared to inflammatory rhetoric and partisan attacks. Activists seeking to build broad coalitions or promote complex policy solutions thus face an inherent disadvantage in the algorithmic marketplace of ideas.

The temporal dynamics of algorithmic systems introduce additional complications. Social media feeds prioritize recency, creating what scholars describe as a “permanent present” where historical context and long-term trends are obscured by the constant flux of new content. This presentism can undermine political movements that require sustained attention to achieve their goals. Issues that might benefit from persistent advocacy over months or years struggle to maintain visibility in an environment where yesterday’s crisis has already been supplanted by today’s trending topic. The short attention spans fostered by these systems may contribute to what critics call “issue cycling“—rapid movement from one concern to another without achieving substantive progress on any.

Network effects and viral dynamics in algorithmic systems create winner-take-all scenarios where certain messages, activists, or movements receive disproportionate attention while others remain marginalized. The mechanisms of virality—though not fully understood—appear to favor content that is easily digestible, emotionally resonant, and compatible with existing cultural schemas. This creates systemic barriers for activists promoting radical ideas or representing communities whose experiences fall outside mainstream narratives. The democratizing potential of social media, which promises to amplify marginalized voices, is thus constrained by the very systems that determine content distribution.

The commercialization of activism represents another consequence of algorithmic mediation. As influencers and activist organizations compete for attention in algorithm-driven ecosystems, there is pressure to adopt strategies that maximize engagement metrics. This can lead to what scholars term “movement entrepreneurship“—where activists function more like content creators or brand managers than grassroots organizers. The professionalization and celebritization of activism may enhance certain aspects of movement capacity, such as fundraising and media visibility, but critics worry it can also hollow out the participatory and egalitarian ethos traditionally associated with social movements.

Moreover, the data extraction practices underlying social media platforms‘ business models have created new forms of vulnerability for activists. Every interaction on these platforms generates data that can be analyzed, packaged, and potentially used for surveillance or targeting. Governments and private actors have increasingly sophisticated tools for monitoring activist networks, identifying key organizers, predicting protest activity, and even preemptively disrupting movements. The same data infrastructures that enable activists to organize and communicate also create digital trails that can be exploited by those seeking to suppress dissent. This surveillance capitalism, as scholar Shoshana Zuboff terms it, fundamentally alters the calculus of political activism, requiring activists to balance the benefits of digital tools against the risks of comprehensive monitoring.

The internationalization of political activism through social media has generated both opportunities and tensions. Transnational movements can now coordinate across borders with unprecedented ease, building solidarity around shared concerns like climate change or human rights. However, the cultural decontextualization that occurs when messages circulate globally can lead to misunderstandings or the imposition of frameworks that may not be appropriate for local conditions. Western-centric perspectives can dominate online discourse, sometimes overshadowing or distorting the priorities of activists in other regions. The power asymmetries present in offline geopolitics are often replicated and sometimes amplified in digital spaces.

Platform governance has emerged as a critical battleground for activists. Decisions about content moderation, account suspension, algorithmic design, and data policies are made by private companies with limited public accountability. Activists have increasingly turned their attention to these meta-political questions, organizing campaigns to pressure platforms to change their policies or advocating for government regulation of these digital public squares. The creation of oversight boards, transparency reports, and external audits represents tentative steps toward more accountable platform governance, but critics argue these reforms remain insufficient given the scale and significance of these companies’ social influence.

Looking forward, several emerging technologies promise to further complicate the relationship between social media and political activism. Artificial intelligence systems capable of generating realistic fake videos, coordinated bot networks that can artificially inflate the appearance of support for particular positions, and micro-targeting techniques that deliver personalized political messages based on psychological profiles all represent evolving threats to authentic democratic discourse. Simultaneously, decentralized platforms using blockchain technology and other alternative architectures may offer activists tools that are more resistant to corporate control or governmental censorship, though these technologies bring their own challenges and limitations.

The fundamental question confronting contemporary activism is whether social media platforms can be reformed to better serve democratic values or whether their core design and business models are fundamentally incompatible with healthy political engagement. Optimists point to the unprecedented capacity for coordination, information sharing, and voice amplification these tools provide. Pessimists warn that the extractive logic of surveillance capitalism, combined with the psychological manipulation enabled by algorithmic systems, poses existential threats to democratic self-governance. The resolution of this tension will likely determine not only the efficacy of political activism in the coming decades but the viability of democratic institutions more broadly in an increasingly digital world.

Thanh niên sử dụng mạng xã hội để tham gia hoạt động chính trị và vận động xã hội trực tuyến

Thanh niên sử dụng mạng xã hội để tham gia hoạt động chính trị và vận động xã hội trực tuyến

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

27. According to the passage, the main difference between traditional mass media and social media platforms is:

A. the speed of information delivery

B. who determines which content reaches audiences

C. the accuracy of political information

D. the cost of accessing information

28. The author describes algorithms as “black boxes” to emphasize their:

A. commercial value to companies

B. technological sophistication

C. lack of transparency

D. illegal operations

29. Research shows that algorithmic systems favor content that:

A. provides balanced perspectives

B. promotes compromise

C. elicits strong emotional reactions

D. comes from credible sources

30. The concept of “permanent present” refers to:

A. the constant availability of social media

B. the prioritization of recent content over historical context

C. the timeless nature of viral posts

D. the future of digital activism

31. According to the passage, surveillance capitalism creates risks for activists by:

A. preventing them from using digital tools entirely

B. making all online activity illegal

C. generating data that can be used for monitoring and suppression

D. forcing activists to abandon social media platforms

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each consequence with the correct aspect of algorithmic systems.

Write the correct letter, A-H, next to questions 32-36.

Aspects:

- A. Temporal dynamics

- B. Network effects

- C. Commercialization pressures

- D. Data extraction

- E. Internationalization

- F. Emotional bias

- G. Opacity

- H. Platform governance

32. Creates vulnerability through comprehensive monitoring capabilities

33. Disadvantages nuanced arguments in favor of inflammatory rhetoric

34. Causes certain messages to receive disproportionate attention

35. Encourages activists to function like content creators or brand managers

36. Can lead to cultural misunderstandings when messages circulate globally

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What do scholars call the rapid movement between different political concerns without making substantial progress?

38. What term does Shoshana Zuboff use to describe the business model based on data extraction?

39. What type of technology might offer activists tools more resistant to corporate control?

40. According to pessimists, what does algorithmic manipulation pose threats to?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- C

- C

- B

- C

- FALSE

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- slacktivism

- user engagement

- surveil

- media literacy

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- NO

- YES

- G

- E

- A

- D

- desensitization / emotional exhaustion

- reward mechanisms

- continuous partial attention

- Cognitive biases

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- C

- B

- C

- D

- F

- B

- C

- E

- issue cycling

- surveillance capitalism

- decentralized platforms / blockchain technology

- democratic self-governance / democratic institutions

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: differs, traditional activism, primarily

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, câu 1-2

- Giải thích: Câu mở đầu nói rằng mạng xã hội “fundamentally transformed how people engage in political activism” và nhấn mạnh khả năng tiếp cận hàng triệu người trong vài giờ. Đáp án B (“speed and reach of communication”) là paraphrase chính xác nhất. Các đáp án khác không được nêu như điểm khác biệt chính.

Câu 2: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: hashtag campaigns, illustrate

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói hashtag campaigns “demonstrated how a simple phrase could unite people across different countries and cultures” – đây chính xác là đáp án C. Đây là ví dụ về việc công cụ đơn giản có thể kết nối người dân quốc tế.

Câu 3: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: clicktivism, suggest

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3-6

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rằng “low-barrier participation might actually reduce the likelihood that individuals will take more substantive action” – đây là paraphrase của đáp án C. Clicktivism có thể làm giảm các hình thức tham gia thực chất hơn.

Câu 4: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: algorithms, criticized

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn chỉ ra thuật toán “promoting content that generates strong emotional reactions” và dẫn đến “amplification of extreme viewpoints and creation of echo chambers”. Đáp án B tóm tắt chính xác những phê bình này.

Câu 5: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: most effective when

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Câu văn “When social media is used as one tool among many—complementing rather than replacing traditional activism—it can significantly enhance the effectiveness” trực tiếp ủng hộ đáp án C.

Câu 6: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: completely replaced, traditional forms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, câu 2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói các hình thức truyền thống “have been complemented—and in some cases replaced” – không phải hoàn toàn thay thế. Từ “completely” làm cho câu này sai.

Câu 7: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: live streaming, document, real-time

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “live streaming capabilities allow activists to coordinate protests, share real-time updates, and document incidents as they happen”. Câu này đúng hoàn toàn.

Câu 8: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: social media companies, actively support

- Vị trí trong bài: Không có thông tin

- Giải thích: Bài viết không đề cập đến việc các công ty mạng xã hội có chủ động hỗ trợ hoạt động chính trị hay không.

Câu 9: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: misinformation, spreads faster, fact-checkers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: Câu “The speed at which information travels on social media often outpaces the ability of fact-checkers to verify claims” khớp hoàn toàn với câu hỏi.

Câu 10: slacktivism

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: Critics, term, online activism, little effort

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “online activism, sometimes dismissively called ‘clicktivism’ or ‘slacktivism'”. Cả hai từ đều đúng, nhưng “slacktivism” gợi ý mạnh mẽ hơn về việc thiếu nỗ lực.

Câu 11: user engagement

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: algorithms, designed, maximize

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 2

- Giải thích: “These algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement” – từ khóa chính xác là “user engagement”.

Câu 12: surveil

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: governments, corporations, social media, activists

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “governments and corporations are also adapting, sometimes using the same platforms to surveil activists” – từ “surveil” là đáp án chính xác.

Câu 13: media literacy

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: success, digital age, requires

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Success in the digital age requires media literacy, critical thinking” – “media literacy” là từ đầu tiên trong danh sách yêu cầu.

Chiến lược làm bài IELTS Reading hiệu quả giúp đạt band điểm cao

Chiến lược làm bài IELTS Reading hiệu quả giúp đạt band điểm cao

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: constant exposure, inevitably, increased activism

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Tác giả nói rằng tiếp xúc liên tục với nội dung chính trị có thể dẫn đến “emotional exhaustion and desensitization” và thậm chí “political apathy over time” – ngược lại với việc tăng hành động. Quan điểm tác giả mâu thuẫn với câu hỏi.

Câu 15: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: online communication, lacks, social cues, moderate disagreements

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Tác giả nói “it can also reduce the social cues and empathy that typically moderate in-person disagreements” – đồng ý với quan điểm trong câu hỏi.

Câu 16: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: platforms, intentionally design, addicted

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói về reward mechanisms và addictive patterns nhưng không nói rõ liệu các nền tảng có cố ý thiết kế để làm người dùng nghiện nội dung chính trị hay không. Đây là về tính chất tổng quát của thiết kế, không cụ thể về mục đích.

Câu 17: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: metrics, always improve, quality

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: Tác giả nói rằng các chỉ số này có thể dẫn đến “performative activism” – tham gia để cải thiện hình ảnh xã hội hơn là cam kết thật sự. Điều này cho thấy chúng không “always improve quality”, mâu thuẫn với câu hỏi.

Câu 18: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: mindful engagement, reduce, negative effects

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, câu đầu

- Giải thích: “research suggests that mindful engagement with social media can mitigate many negative effects” – tác giả đồng ý với quan điểm này.

Câu 19: G

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Từ khóa: moral outrage fatigue

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Đoạn này thảo luận về “moral outrage fatigue” và “emotional exhaustion” do tiếp xúc liên tục với nội dung chính trị đau lòng. Heading G (“Emotional exhaustion from constant political information”) phù hợp nhất.

Câu 20: E

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Từ khóa: marginalized, support

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: Đoạn này nói về việc cá nhân bị thiệt thòi tìm thấy mạng lưới hỗ trợ trực tuyến và “collective identity can be empowering”. Heading E (“Positive effects of online political communities”) là phù hợp.

Câu 21: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Từ khóa: likes, shares, follower counts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: Đoạn này bàn về “gamification elements” như likes và shares tạo ra “quantifiable metrics” và “reward mechanisms”. Heading A (“The role of reward systems in online behavior”) chính xác nhất.

Câu 22: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Từ khóa: context collapse

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7

- Giải thích: Đoạn này thảo luận về “context collapse” khi “diverse audiences coexist in the same space” trên mạng xã hội. Heading D (“The challenge of managing multiple audiences”) phù hợp.

Câu 23: desensitization / emotional exhaustion

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: constant stream, distressing content, lead to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “the relentless barrage of distressing content can eventually lead to emotional exhaustion and desensitization”. Cả hai từ đều đúng.

Câu 24: reward mechanisms

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: built into platforms, addictive behaviors, gambling

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “The reward mechanisms built into social media platforms can create addictive patterns of behavior… in ways similar to gambling”.

Câu 25: continuous partial attention

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: state, constantly monitor devices, without focusing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: Bài viết định nghĩa “continuous partial attention” là “a state where individuals are constantly monitoring their devices while struggling to focus deeply on any single task”.

Câu 26: Cognitive biases

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: amplified, social media environments, process political information

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, câu đầu

- Giải thích: “Cognitive biases are amplified in social media environments, affecting how individuals process political information” – khớp chính xác.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main difference, traditional mass media, social media

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Unlike traditional mass media, where editorial gatekeepers determined which information reached the public, contemporary digital platforms employ sophisticated algorithms”. Sự khác biệt chính là ai quyết định nội dung – đáp án B.

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: black boxes, emphasize

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Thuật ngữ “black boxes” được dùng để mô tả “internal logic remains inscrutable to outside observers”. Điều này nhấn mạnh sự thiếu minh bạch – đáp án C.

Câu 29: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: research shows, favor

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Several studies have demonstrated that content eliciting strong emotional reactions… receives preferential treatment in recommendation systems”. Đáp án C chính xác.

Câu 30: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: permanent present, refers to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Permanent present” được định nghĩa là nơi “historical context and long-term trends are obscured by the constant flux of new content” – nghĩa là ưu tiên nội dung gần đây hơn bối cảnh lịch sử, đáp án B.

Câu 31: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: surveillance capitalism, risks

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Every interaction… generates data that can be analyzed, packaged, and potentially used for surveillance or targeting” và “create digital trails that can be exploited by those seeking to suppress dissent”. Đáp án C chính xác.

Câu 32: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: vulnerability, monitoring

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7

- Giải thích: “Data extraction” tạo ra “new forms of vulnerability for activists” thông qua “comprehensive monitoring”. Đáp án D (Data extraction).

Câu 33: F

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: disadvantages nuanced arguments, inflammatory rhetoric

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: Đoạn này nói về “structural bias toward emotionally provocative material” và “Nuanced arguments… are systematically disadvantaged compared to inflammatory rhetoric”. Đây là về “Emotional bias” – đáp án F.

Câu 34: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: disproportionate attention

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “Network effects and viral dynamics… create winner-take-all scenarios where certain messages… receive disproportionate attention”. Đáp án B (Network effects).

Câu 35: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: function like content creators, brand managers

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “The commercialization of activism” dẫn đến “movement entrepreneurship—where activists function more like content creators or brand managers”. Đáp án C (Commercialization pressures).

Câu 36: E

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: cultural misunderstandings, circulate globally

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: “The internationalization of political activism” và “cultural decontextualization that occurs when messages circulate globally can lead to misunderstandings”. Đáp án E (Internationalization).

Câu 37: issue cycling

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: scholars call, rapid movement, concerns, without substantial progress

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: “critics call ‘issue cycling’—rapid movement from one concern to another without achieving substantive progress on any”.

Câu 38: surveillance capitalism

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: Shoshana Zuboff, term, business model, data extraction

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: “This surveillance capitalism, as scholar Shoshana Zuboff terms it” – thuật ngữ chính xác.

Câu 39: decentralized platforms / blockchain technology

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: technology, offer activists, resistant, corporate control

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “decentralized platforms using blockchain technology… may offer activists tools that are more resistant to corporate control”. Cả hai đáp án đều chấp nhận.

Câu 40: democratic self-governance / democratic institutions

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: pessimists, algorithmic manipulation, poses threats

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 11, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Pessimists warn that… psychological manipulation enabled by algorithmic systems, poses existential threats to democratic self-governance” và “the viability of democratic institutions”. Cả hai đáp án đều đúng.

Từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề mạng xã hội và hoạt động chính trị

Từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề mạng xã hội và hoạt động chính trị

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mobilize | v | /ˈməʊbəlaɪz/ | huy động, tập hợp | The ability to mobilize large numbers of people quickly | mobilize support/resources |

| spread virally | v phrase | /spred ˈvaɪrəli/ | lan truyền nhanh chóng | It can spread virally across networks | go viral, spread rapidly |

| substantial | adj | /səbˈstænʃəl/ | đáng kể, lớn lao | No longer need substantial financial resources | substantial evidence/change |

| accountability | n | /əˌkaʊntəˈbɪləti/ | trách nhiệm giải trình | Holding authorities accountable | public accountability |

| transparency | n | /trænsˈpærənsi/ | tính minh bạch, trong suốt | The transparency afforded by these technologies | lack of transparency |

| illusion | n | /ɪˈluːʒən/ | ảo tưởng | Create an illusion of participation | create/maintain an illusion |

| echo chamber | n phrase | /ˈekəʊ ˈtʃeɪmbə(r)/ | buồng vang (môi trường chỉ nghe ý kiến tương đồng) | Creation of echo chambers | create/exist in echo chambers |

| polarization | n | /ˌpəʊləraɪˈzeɪʃən/ | sự phân cực | Deepen political polarization | increasing polarization |

| misinformation | n | /ˌmɪsɪnfəˈmeɪʃən/ | thông tin sai lệch | Misinformation presents a major challenge | spread/combat misinformation |

| dissemination | n | /dɪˌsemɪˈneɪʃən/ | sự phổ biến, lan truyền | The rapid dissemination of false information | information dissemination |

| legitimate | adj | /lɪˈdʒɪtɪmət/ | hợp pháp, chính đáng | Undermine legitimate activist efforts | legitimate concern/interest |

| tangible | adj | /ˈtændʒəbəl/ | hữu hình, cụ thể | Convert online support into tangible action | tangible results/benefits |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proliferation | n | /prəˌlɪfəˈreɪʃən/ | sự gia tăng nhanh chóng | The proliferation of social media | nuclear proliferation |

| implications | n | /ˌɪmplɪˈkeɪʃənz/ | hệ quả, ảnh hưởng | Implications that extend far beyond | have implications for |

| moral outrage | n phrase | /ˈmɒrəl ˈaʊtreɪdʒ/ | sự phẫn nộ về mặt đạo đức | Moral outrage fatigue | express/feel moral outrage |

| desensitization | n | /diːˌsensɪtaɪˈzeɪʃən/ | sự mất nhạy cảm | Lead to desensitization | emotional desensitization |

| asynchronous | adj | /eɪˈsɪŋkrənəs/ | không đồng bộ | The asynchronous nature of online communication | asynchronous communication |

| empathy | n | /ˈempəθi/ | sự đồng cảm | Reduce the empathy that moderates disagreements | show/feel empathy |

| disinhibition | n | /ˌdɪsɪnhɪˈbɪʃən/ | sự mất kiềm chế | The online disinhibition effect | social disinhibition |

| marginalized | adj | /ˈmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪzd/ | bị gạt ra ngoài lề | Individuals who feel marginalized | marginalized communities |

| self-efficacy | n | /ˌself ˈefɪkəsi/ | niềm tin vào khả năng bản thân | Strengthen political self-efficacy | sense of self-efficacy |

| gamification | n | /ˌɡeɪmɪfɪˈkeɪʃən/ | trò chơi hóa | The gamification elements in platforms | gamification of learning |

| performative | adj | /pəˈfɔːmətɪv/ | mang tính biểu diễn (không chân thành) | Performative activism | performative gesture |

| compulsively | adv | /kəmˈpʌlsɪvli/ | một cách cưỡng bức, nghiện | Compulsively check their feeds | compulsively eat/shop |

| context collapse | n phrase | /ˈkɒntekst kəˈlæps/ | sự sụp đổ bối cảnh (khi nhiều đối tượng khác nhau cùng thấy một nội dung) | The phenomenon of context collapse | experience context collapse |

| confirmation bias | n phrase | /ˌkɒnfəˈmeɪʃən ˈbaɪəs/ | thiên kiến xác nhận | Confirmation bias is pronounced | suffer from confirmation bias |

| mitigate | v | /ˈmɪtɪɡeɪt/ | giảm nhẹ, làm dịu | Mindful engagement can mitigate negative effects | mitigate risks/damage |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ascendancy | n | /əˈsendənsi/ | sự thống trị, vượt trội | The ascendancy of social media platforms | gain ascendancy over |

| conduit | n | /ˈkɒndjuɪt/ | kênh dẫn, phương tiện | Primary conduits for political information | serve as a conduit |

| mediated | adj | /ˈmiːdieɪtɪd/ | được trung gian hóa | Democratic discourse is mediated | digitally mediated |

| gatekeeper | n | /ˈɡeɪtkiːpə(r)/ | người kiểm soát thông tin | Editorial gatekeepers determined content | act as gatekeeper |

| curate | v | /kjʊəˈreɪt/ | tuyển chọn, sắp xếp | Algorithms that curate content | curate a collection |

| opacity | n | /əʊˈpæsəti/ | tính mờ đục, thiếu minh bạch | The opacity of algorithms | opacity of decision-making |

| inscrutable | adj | /ɪnˈskruːtəbəl/ | khó hiểu, bí ẩn | Internal logic remains inscrutable | inscrutable expression |

| inadvertently | adv | /ˌɪnədˈvɜːtəntli/ | vô ý, không cố ý | Inadvertently shaping political discourse | inadvertently reveal/cause |

| amplification | n | /ˌæmplɪfɪˈkeɪʃən/ | sự khuếch đại | Algorithmic amplification of content | signal amplification |

| inflammatory | adj | /ɪnˈflæmətri/ | kích động, gây bất bình | Inflammatory rhetoric receives attention | inflammatory remarks |

| presentism | n | /ˈprezəntɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa hiện tại (chỉ chú ý đến hiện tại) | This presentism can undermine movements | suffer from presentism |

| marginalized | adj | /ˈmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪzd/ | bị gạt ra lề | Messages remain marginalized | marginalized voices |

| entrepreneurship | n | /ˌɒntrəprəˈnɜːʃɪp/ | tinh thần khởi nghiệp | Movement entrepreneurship emerges | social entrepreneurship |

| extraction | n | /ɪkˈstrækʃən/ | sự khai thác | Data extraction practices | resource extraction |

| surveillance | n | /sɜːˈveɪləns/ | sự giám sát | Government surveillance of activists | under surveillance |

| preemptively | adv | /priˈemptɪvli/ | một cách phủ đầu, ngăn chặn trước | Preemptively disrupting movements | act preemptively |

| asymmetry | n | /eɪˈsɪmətri/ | sự bất cân xứng | Power asymmetries are replicated | information asymmetry |

| accountability | n | /əˌkaʊntəˈbɪləti/ | trách nhiệm giải trình | Limited public accountability | demand accountability |

| efficacy | n | /ˈefɪkəsi/ | hiệu quả, hiệu lực | Determine the efficacy of activism | demonstrate efficacy |

| viability | n | /ˌvaɪəˈbɪləti/ | tính khả thi | The viability of democratic institutions | economic viability |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề về ảnh hưởng của mạng xã hội đối với hoạt động chính trị không chỉ là một đề tài nóng trong xã hội đương đại mà còn là nội dung thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS Reading. Thông qua đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được thực hành với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần, từ Easy ở Passage 1 (phù hợp band 5.0-6.5) đến Medium ở Passage 2 (band 6.0-7.5) và Hard ở Passage 3 (band 7.0-9.0). Mỗi passage cung cấp góc nhìn khác nhau về chủ đề: từ những thay đổi cơ bản trong cách thức hoạt động chính trị, đến tác động tâm lý của sự tham gia trực tuyến, và cuối cùng là những phân tích sâu sắc về quản trị thuật toán và tương lai của diễn ngôn chính trị số.

Đề thi đã bao gồm đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng câu hỏi khác nhau, giúp bạn làm quen với các format phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading thực tế. Phần đáp án chi tiết không chỉ cho bạn biết câu trả lời đúng mà còn giải thích tại sao đúng, vị trí thông tin trong passage, và cách nhận diện paraphrase – kỹ năng quan trọng nhất để đạt band điểm cao trong IELTS Reading.

Bộ từ vựng quan trọng được tổng hợp theo từng passage sẽ là tài liệu quý giá cho việc học từ mới. Hãy chú ý không chỉ học nghĩa tiếng Việt mà còn cách sử dụng từ trong ngữ cảnh và các collocations thường đi kèm. Việc làm chủ những từ vựng này sẽ giúp bạn không chỉ trong phần Reading mà còn cả Writing và Speaking.

Hãy nhớ rằng, luyện tập đều đặn với các đề thi đầy đủ như thế này, phân tích kỹ các lỗi sai, và học từ vựng có hệ thống là ba yếu tố quyết định sự thành công trong IELTS Reading. Chúc bạn ôn tập hiệu quả và đạt được band điểm mục tiêu!