Mở Bài

Chủ đề năng lượng tái tạo và ảnh hưởng của nó đến các chiến lược an ninh quốc gia đang trở thành một trong những chủ đề phổ biến trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Với xu hướng toàn cầu hóa và biến đổi khí hậu, các quốc gia ngày càng chú trọng đến việc chuyển đổi nguồn năng lượng, không chỉ vì lý do môi trường mà còn vì các lý do chiến lược, an ninh. Chủ đề này thường xuyên xuất hiện trong các đề thi IELTS Academic Reading với độ khó từ trung bình đến cao.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh gồm 3 passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard. Bạn sẽ được luyện tập với các dạng câu hỏi đa dạng hoàn toàn giống thi thật, kèm theo đáp án chi tiết và giải thích cụ thể cho từng câu. Đặc biệt, bạn sẽ học được hàng chục từ vựng học thuật quan trọng liên quan đến năng lượng, an ninh quốc gia và chính sách công.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với format thi thật và nâng cao kỹ năng đọc hiểu học thuật một cách hiệu quả nhất.

1. Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test bao gồm 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi phải hoàn thành trong 60 phút. Đây là thử thách về cả tốc độ đọc và khả năng phân tích thông tin học thuật.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó Easy)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó Medium)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó Hard)

Lưu ý rằng không có thời gian bổ sung để chép đáp án sang phiếu trả lời, vì vậy bạn cần quản lý thời gian thật tốt và ghi đáp án trực tiếp vào answer sheet trong khi làm bài.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hoặc không được nhắc đến

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn tương ứng

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu với từ trong bài

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Rise of Renewable Energy in National Planning

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

In recent decades, renewable energy has moved from the margins of energy policy to become a central component of national security strategies around the world. This transformation reflects not only growing environmental concerns but also the recognition that energy independence can significantly enhance a nation’s geopolitical position. Countries that were once entirely dependent on imported fossil fuels are now investing billions in solar, wind, and hydroelectric power to reduce their vulnerability to supply disruptions and price fluctuations.

The shift toward renewable energy began in earnest following the oil crises of the 1970s, when many nations realized the dangers of over-reliance on foreign energy sources. Denmark, for instance, responded to these crises by developing an ambitious wind energy program. Today, wind power provides approximately 50% of Denmark’s electricity needs, making it one of the world’s leaders in renewable energy integration. This achievement has not only reduced Denmark’s carbon emissions but has also created a thriving export industry for wind turbine technology, demonstrating how energy policy can simultaneously address security and economic concerns.

Energy security traditionally focused on ensuring stable supplies of oil and gas, often requiring military protection of supply routes and close relationships with producer nations. However, the renewable energy paradigm offers a fundamentally different approach. Solar panels and wind turbines can be deployed domestically, reducing the need for vulnerable supply chains that stretch across oceans and conflict zones. This decentralization of energy production means that natural disasters, political instability, or acts of terrorism in one region need not cripple a nation’s entire energy infrastructure.

Germany’s Energiewende, or “energy transition,” exemplifies this new approach to energy security. Launched in 2010, this policy aims to phase out nuclear power while dramatically increasing renewable energy production. By 2020, renewable sources accounted for over 45% of Germany’s electricity generation. While the transition has faced challenges, including higher electricity prices and the need for grid modernization, it has significantly reduced Germany’s dependence on Russian natural gas—a strategic vulnerability that became painfully apparent during recent geopolitical tensions.

The economic implications of renewable energy adoption extend beyond mere energy independence. The renewable energy sector has become a major source of employment in many countries. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, the sector employed 11.5 million people globally in 2019, with that number expected to rise to nearly 30 million by 2030. These jobs are often located in rural or economically disadvantaged areas where wind farms and solar installations are built, contributing to regional development and reducing economic inequalities that can threaten social stability.

Moreover, investment in renewable infrastructure creates technological capabilities that enhance a nation’s overall competitiveness. Countries that develop expertise in renewable energy technologies position themselves advantageously in the growing global market for clean energy solutions. China, for example, has become the world’s largest producer of solar panels and wind turbines, leveraging this position to extend its influence through energy partnerships and technology exports. This demonstrates how renewable energy leadership can translate into broader strategic advantages.

The national security benefits of renewable energy are not limited to large, wealthy nations. Small island developing states, which face existential threats from climate change and often spend disproportionate amounts on imported diesel fuel for electricity generation, are increasingly turning to renewable sources. The island nation of Samoa aims to achieve 100% renewable electricity by 2025, primarily through hydroelectric and solar power. This transition will not only reduce carbon emissions but will also free up government resources currently spent on fuel imports for investment in education, healthcare, and climate adaptation measures.

However, the transition to renewable energy also creates new security challenges that must be addressed. Cybersecurity threats to smart grids and renewable energy infrastructure are growing concerns. Additionally, the production of solar panels and batteries requires rare earth elements and other materials that are concentrated in a few countries, potentially creating new dependencies. Nations must carefully consider these factors as they develop their renewable energy strategies, ensuring that solving one security challenge does not inadvertently create another.

Questions 1-6

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- Denmark’s wind energy program was initiated as a response to energy crises in the 1970s.

- Renewable energy sources eliminate all risks associated with energy supply disruptions.

- Germany’s Energiewende policy includes plans to eliminate nuclear power production.

- The renewable energy sector employed more than 10 million people worldwide in 2019.

- China exports more renewable energy technology than any other country.

- Samoa has already achieved its goal of 100% renewable electricity generation.

Questions 7-10

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- Traditional energy security often required __ of oil and gas transportation routes.

- The renewable energy transition in Germany has necessitated improvements to the electricity __.

- Renewable energy jobs are frequently created in areas that are __ compared to urban centers.

- Small island nations face serious dangers from __ and high costs for imported fuel.

Questions 11-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, what is one advantage of decentralized energy production?

- A) It is always cheaper than centralized systems

- B) It reduces vulnerability to regional disruptions

- C) It requires less technological expertise

- D) It eliminates the need for energy storage

-

The passage suggests that Germany’s energy transition has:

- A) been completed without any difficulties

- B) resulted in complete energy independence

- C) revealed strategic weaknesses in energy policy

- D) eliminated all carbon emissions

-

What new security concern does the passage mention regarding renewable energy?

- A) The high cost of solar panels

- B) Opposition from fossil fuel industries

- C) Concentration of required materials in few countries

- D) Lack of skilled workers in the sector

PASSAGE 2 – Renewable Energy and Military Strategy

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The integration of renewable energy into military operations represents a paradigm shift in defense strategy that extends far beyond environmental considerations. Armed forces worldwide are recognizing that energy efficiency and renewable power sources can provide tactical advantages, reduce logistical vulnerabilities, and fundamentally alter the economics of military deployment. This recognition has transformed renewable energy from a peripheral concern into a core element of military planning and force projection capabilities.

Military fuel consumption presents enormous challenges for modern armed forces. The United States Department of Defense, for instance, is the world’s single largest institutional consumer of petroleum, using approximately 100 million barrels annually. In combat zones, the cost of delivering fuel to forward operating bases can exceed $400 per gallon when accounting for transportation, security, and the risks to personnel involved in supply convoys. Between 2001 and 2010, more than 3,000 American and allied troops and contractors were killed or wounded in attacks on fuel and water resupply convoys in Iraq and Afghanistan. These stark statistics have driven military planners to explore renewable alternatives that could reduce the logistical footprint of deployed forces.

Solar power has emerged as particularly promising for military applications. Portable solar panels can power communications equipment, computers, and battery charging stations without requiring fuel resupply missions. The U.S. Marine Corps has deployed portable solar shelters that significantly reduce generator usage at forward operating bases. These systems not only decrease fuel requirements but also reduce the acoustic signature of military positions—diesel generators can be heard from considerable distances, potentially compromising tactical security. Similarly, solar-powered unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can remain aloft for extended periods, providing persistent surveillance without the range limitations of fuel-powered aircraft.

The strategic implications of military renewable energy adoption extend to base operations and infrastructure. Many military installations are exploring microgrids powered by renewable sources, which can continue operating even if disconnected from civilian power networks—a capability known as “islanding”. This resilience is crucial for maintaining operational readiness during natural disasters or if civilian infrastructure is compromised by attack or sabotage. Naval Air Station Fallon in Nevada, for example, has implemented a geothermal energy system that provides baseload power independent of the civilian grid, enhancing the installation’s ability to function during regional power outages.

Naval forces present unique opportunities and challenges for renewable energy integration. The vast expanses of ocean offer abundant solar and wind resources, yet the demanding operational requirements of naval vessels have historically necessitated energy-dense fossil fuels or nuclear power. However, recent technological advances are changing this equation. The U.S. Navy has tested biofuels derived from algae and plant materials in its ships and aircraft, demonstrating that renewable fuels can meet military performance specifications. Moreover, some navies are exploring hybrid propulsion systems that combine conventional engines with electric motors powered by solar panels and batteries, potentially reducing fuel consumption during low-speed operations such as patrol missions.

The geopolitical ramifications of military renewable energy adoption deserve careful consideration. Nations that reduce their militaries’ dependence on petroleum potentially gain greater strategic flexibility, as their freedom of action becomes less constrained by fuel supply considerations. This could alter calculations regarding power projection and expeditionary warfare. Conversely, countries that currently derive geopolitical influence from petroleum exports may find their strategic leverage diminished if major military consumers shift to renewable sources. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have recognized this risk and are themselves investing heavily in renewable energy, both for domestic use and to maintain relevance in a changing global energy landscape.

Cybersecurity concerns specific to military renewable energy systems warrant attention. Smart grids, battery management systems, and the Internet of Things devices that optimize renewable energy usage create potential vulnerabilities to cyberattacks. An adversary capable of disrupting the power supply to military bases through cyber means could degrade operational capability without firing a shot. Military planners must therefore ensure that renewable energy systems incorporate robust cybersecurity measures and maintain backup systems that can function independently if networked systems are compromised.

The transition to military renewable energy is not without critics. Some analysts argue that the energy density of renewable sources remains insufficient for high-intensity combat operations, particularly for energy-intensive systems like aircraft carriers or heavy armored vehicles. They contend that during actual warfare, as opposed to peacetime operations or counterinsurgency campaigns, fossil fuels and nuclear power will remain indispensable. Proponents respond that even incremental improvements in energy efficiency and partial adoption of renewables can yield significant operational and strategic benefits, and that technological progress continues to enhance renewable energy capabilities.

Looking forward, the convergence of renewable energy technology, energy storage advances, and artificial intelligence for grid management promises to further enhance military renewable energy applications. Next-generation batteries with higher energy densities could power vehicles and equipment previously dependent on liquid fuels. AI-driven predictive analytics could optimize energy usage across military installations, ensuring that renewable sources provide maximum benefit. As these technologies mature, the military advantages of renewable energy will likely become increasingly pronounced, potentially reshaping not just military operations but the broader strategic calculations that underpin national defense policy.

Hệ thống năng lượng mặt trời tại căn cứ quân sự giúp tăng cường an ninh năng lượng và khả năng tác chiến

Hệ thống năng lượng mặt trời tại căn cứ quân sự giúp tăng cường an ninh năng lượng và khả năng tác chiến

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, what is the main reason militaries are adopting renewable energy?

- A) To comply with environmental regulations

- B) To gain tactical and logistical advantages

- C) To reduce greenhouse gas emissions

- D) To improve public relations

-

The cost of $400 per gallon mentioned in paragraph 2 refers to:

- A) the retail price of military-grade fuel

- B) the environmental cost of fuel consumption

- C) the total cost including delivery and security

- D) the price of renewable fuel alternatives

-

What advantage do solar-powered UAVs offer compared to fuel-powered aircraft?

- A) They are cheaper to manufacture

- B) They can fly faster and higher

- C) They can stay airborne for longer periods

- D) They carry heavier payloads

-

The term “islanding” in paragraph 4 refers to:

- A) building military bases on islands

- B) operating independently from civilian power networks

- C) isolating enemy forces on islands

- D) creating energy storage systems

-

Critics of military renewable energy argue that:

- A) renewable energy is too expensive for military use

- B) solar panels are vulnerable to enemy attacks

- C) renewable sources lack sufficient energy density for combat

- D) military personnel are not trained to use renewable systems

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Military forces face significant challenges with fuel consumption, particularly the dangers associated with 19. __ in combat zones. Renewable energy offers solutions such as portable solar panels that can reduce the need for 20. __ and decrease the 21. __ of military positions by eliminating noisy generators. Naval forces are testing 22. __ made from algae and plants, while some ships are exploring 23. __ that combine traditional engines with electric power.

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- The U.S. Department of Defense uses more petroleum than any other single organization.

- All military analysts agree that renewable energy will completely replace fossil fuels in military operations.

- Artificial intelligence will play an important role in future military energy management.

PASSAGE 3 – The Geopolitical Transformation Through Renewable Energy Transition

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The global transition toward renewable energy sources represents not merely a technological evolution but a fundamental restructuring of international power dynamics that rivals in significance the shift from coal to oil in the early twentieth century. This energy transition is recalibrating the balance of geopolitical influence, creating new vulnerabilities while ameliorating longstanding security concerns, and forcing nations to reconceptualize the very foundations of energy security doctrine. The implications extend across multiple dimensions of statecraft: from the redistribution of economic power to the transformation of alliance structures, and from the emergence of novel security threats to the potential for unprecedented international cooperation on climate mitigation.

Traditional energy geopolitics has been characterized by the concentration of fossil fuel resources in specific geographic regions, creating asymmetric power relationships between producer and consumer nations. The Middle East’s dominance in oil production has shaped global politics for decades, conferring substantial geopolitical leverage on nations with large reserves while rendering consuming nations vulnerable to supply disruptions and price manipulation. This structural dependence has driven foreign policy decisions, military interventions, and alliance formations, creating a complex web of relationships in which energy security considerations often superseded other policy priorities. The petrodollar system, whereby oil is predominantly traded in U.S. dollars, has reinforced American financial hegemony while tying the fate of oil-producing nations to Western financial systems.

The renewable energy transition promises to fundamentally disrupt these established patterns. Unlike fossil fuels, renewable energy resources—solar radiation, wind, geothermal heat, and hydroelectric potential—are far more geographically dispersed and cannot be monopolized by a small number of states. This democratization of energy could reduce the geopolitical significance of current energy-producing regions while elevating nations that effectively harness renewable resources or develop technological leadership in renewable energy systems. However, this transition creates its own dependency structures, particularly regarding the critical minerals required for renewable energy technologies and the concentration of manufacturing capacity in specific countries.

The manufacture of renewable energy equipment, especially solar panels, batteries, and wind turbines, has become increasingly concentrated in China, which now produces approximately 70% of the world’s solar panels and holds dominant positions in battery production and wind turbine manufacturing. This concentration confers strategic advantages analogous to, though distinct from, those previously held by oil producers. China’s Belt and Road Initiative increasingly incorporates renewable energy projects, extending Chinese influence through infrastructure development and creating potential dependencies among recipient nations. The strategic implications become apparent when considering that China could potentially leverage its dominance in renewable energy manufacturing to advance geopolitical objectives, much as oil producers have historically used energy as a diplomatic tool.

Critical mineral supplies represent perhaps the most significant new vulnerability in renewable energy geopolitics. Lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements, and other materials essential for batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines are unevenly distributed globally and often concentrated in countries with questionable governance or located in politically unstable regions. The Democratic Republic of Congo supplies approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt, while China controls the majority of rare earth element processing capacity. This concentration creates strategic chokepoints that could be exploited during international conflicts or used as leverage in diplomatic negotiations. Nations pursuing renewable energy transitions must therefore develop strategies to diversify supply chains, invest in recycling technologies, or cultivate diplomatic relationships with critical mineral suppliers—recapitulating, in new form, the resource dependencies that characterized fossil fuel geopolitics.

The implications for international alliances and partnerships are profound. Traditional energy security alliances, such as those between the United States and Gulf monarchies, may diminish in significance as oil dependence decreases, potentially necessitating the formation of new partnerships based on renewable energy cooperation, technology sharing, or critical mineral access. The European Union’s hydrogen strategy, which envisions importing renewable hydrogen from North Africa, could create new energy relationships transcending traditional alignments. Similarly, the concept of “energy sovereignty“—the ability to meet energy needs from domestic resources—becomes more achievable for many nations through renewable energy, potentially reducing the geopolitical relevance of traditional energy security alliances.

Climate change itself constitutes an increasingly significant national security threat that intersects with renewable energy considerations. Rising sea levels threaten coastal military installations and urban centers, changing precipitation patterns affect agricultural production and water supplies, and extreme weather events increase demands on military forces for disaster response. The renewable energy transition, by mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, addresses these security threats at their source. However, the pace of transition varies dramatically between nations, creating potential conflicts between countries suffering climate impacts and those whose continued fossil fuel use contributes to global warming. This dynamic introduces a normative dimension to energy security, where the moral imperative to prevent catastrophic climate change increasingly influences security policy.

The potential for renewable energy to reduce international conflicts over resources deserves careful examination. Some analysts argue that the diffuse nature of renewable energy resources, combined with decreased competition for concentrated fossil fuel reserves, could reduce interstate tensions and the likelihood of resource wars. The decentralized character of renewable energy production might also reduce the strategic value of controlling energy chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz, potentially diminishing flashpoints for military conflict. However, counterarguments suggest that competition over critical minerals, water resources for hydroelectric power, and optimal locations for renewable energy production could generate new conflicts, while the disruption of fossil fuel-dependent economies could create instability in currently stable regions.

Looking toward the future, the intersection of renewable energy with emerging technologies—artificial intelligence, blockchain, autonomous systems, and advanced materials science—will likely create additional layers of complexity in energy geopolitics. Distributed ledger technologies could enable peer-to-peer energy trading that bypasses traditional utility structures and national regulatory frameworks, potentially challenging state control over energy systems. AI-optimized smart grids spanning multiple countries could necessitate unprecedented levels of international technical cooperation and create vulnerabilities to cyberattacks that could affect multiple nations simultaneously. The nation-states that successfully navigate these technological convergences while developing resilient, sustainable energy systems will be positioned to exercise disproportionate influence in the emerging geopolitical order.

The renewable energy transition thus represents a historical inflection point in the evolution of international relations, comparable to previous paradigm shifts that reshaped global power structures. While it offers the promise of reduced resource conflicts, greater energy independence, and climate stabilization, it simultaneously creates new dependencies, vulnerabilities, and potential sources of interstate tension. National security strategies must evolve to address this complex landscape, balancing the pursuit of energy sovereignty against the need for international cooperation, investing in both renewable energy capacity and critical mineral security, and developing the technological capabilities necessary to thrive in an energy system fundamentally different from that which has prevailed for the past century. The nations that most effectively adapt their security doctrines to this new reality will be those best positioned to protect their interests and exercise influence in the decades ahead.

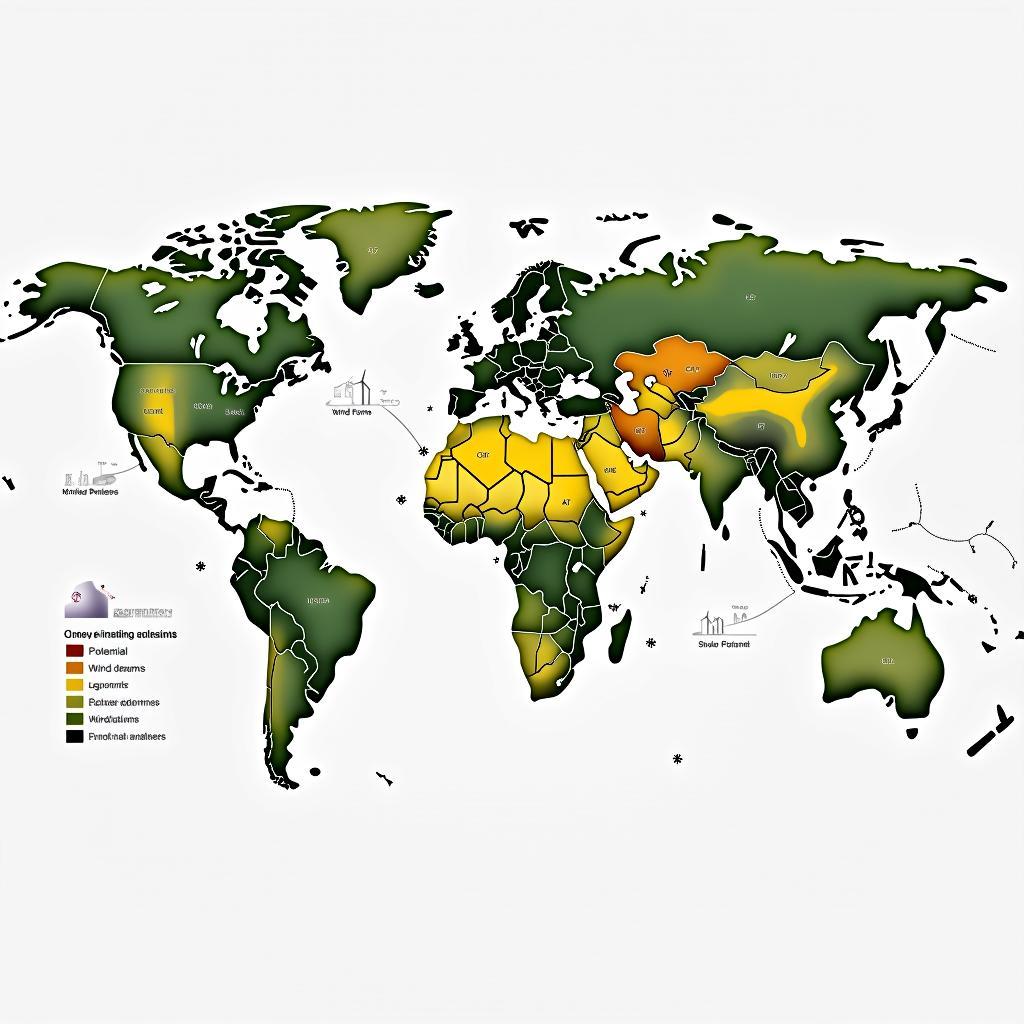

Bản đồ toàn cầu thể hiện sự phân bố nguồn năng lượng tái tạo và ảnh hưởng đến chiến lược an ninh quốc gia

Bản đồ toàn cầu thể hiện sự phân bố nguồn năng lượng tái tạo và ảnh hưởng đến chiến lược an ninh quốc gia

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

-

According to the passage, the renewable energy transition is comparable to:

- A) the discovery of electricity

- B) the Industrial Revolution

- C) the shift from coal to oil

- D) the invention of the steam engine

-

The term “petrodollar system” refers to:

- A) a currency used only in oil-producing countries

- B) the practice of trading oil predominantly in U.S. dollars

- C) a banking system exclusive to petroleum companies

- D) the total value of global oil reserves

-

What percentage of the world’s solar panels does China currently produce?

- A) 50%

- B) 60%

- C) 70%

- D) 80%

-

The Democratic Republic of Congo is significant in renewable energy geopolitics because:

- A) it has the world’s largest solar energy potential

- B) it supplies most of the world’s cobalt

- C) it manufactures the majority of batteries

- D) it controls rare earth element processing

-

According to the passage, what is one potential benefit of renewable energy for international relations?

- A) It guarantees complete energy independence for all nations

- B) It eliminates all forms of international competition

- C) It might reduce conflicts over concentrated fossil fuel resources

- D) It removes the need for international alliances

Questions 32-36

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- The unequal power relationships between countries that produce and consume fossil fuels are described as __.

- China’s __ includes renewable energy projects that extend its international influence.

- The concept of __ refers to a country’s ability to meet its energy requirements using domestic resources.

- According to some analysts, the __ of renewable energy resources could reduce competition similar to that for fossil fuels.

- Technologies such as __ could allow individuals to trade energy directly without traditional utility companies.

Questions 37-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Renewable energy resources are more evenly distributed globally than fossil fuels.

- The European Union plans to import renewable hydrogen exclusively from North Africa.

- Climate change poses a growing threat to national security that relates to renewable energy policy.

- All analysts agree that renewable energy will definitely reduce international conflicts.

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- FALSE

- military protection

- grid

- economically disadvantaged

- climate change

- B

- C

- C

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- B

- C

- C

- B

- C

- supply convoys

- fuel resupply missions

- acoustic signature

- biofuels

- hybrid propulsion systems

- YES

- NO

- YES

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- C

- B

- C

- B

- C

- asymmetric power relationships

- Belt and Road Initiative

- energy sovereignty

- diffuse nature / decentralized character

- distributed ledger technologies / blockchain

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- YES

- NO

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Denmark, wind energy program, 1970s, oil crises

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “The shift toward renewable energy began in earnest following the oil crises of the 1970s” và “Denmark, for instance, responded to these crises by developing an ambitious wind energy program.” Điều này khớp hoàn toàn với phát biểu trong câu hỏi.

Câu 2: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: eliminate all risks, supply disruptions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: Câu hỏi khẳng định năng lượng tái tạo loại bỏ TẤT CẢ rủi ro, nhưng đoạn 8 chỉ ra rằng “the transition to renewable energy also creates new security challenges that must be addressed” bao gồm cybersecurity threats và dependencies mới. Do đó phát biểu này sai.

Câu 3: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Germany, Energiewende, eliminate nuclear power

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “this policy aims to phase out nuclear power while dramatically increasing renewable energy production.” “Phase out” đồng nghĩa với “eliminate”, vậy phát biểu đúng.

Câu 4: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: 11.5 million, 2019, renewable energy sector

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu rõ “the sector employed 11.5 million people globally in 2019”, khớp chính xác với câu hỏi (11.5 million > 10 million).

Câu 5: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: China, exports more than any other country

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ nói China là “the world’s largest producer” và có “technology exports”, nhưng không so sánh khối lượng xuất khẩu của China với các nước khác. Không đủ thông tin để xác định.

Câu 6: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Samoa, 100% renewable electricity, already achieved

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Samoa aims to achieve 100% renewable electricity by 2025” (mục tiêu đạt được vào năm 2025), chứ không phải đã đạt được rồi. Câu hỏi dùng “has already achieved” nên sai.

Câu 7: military protection

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: traditional energy security, oil and gas transportation routes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Energy security traditionally focused on ensuring stable supplies of oil and gas, often requiring military protection of supply routes.”

Câu 8: grid

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: Germany, renewable energy transition, electricity improvements

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “While the transition has faced challenges, including higher electricity prices and the need for grid modernization.” Câu hỏi hỏi về “electricity __” và đáp án là “grid”.

Câu 9: economically disadvantaged

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: renewable energy jobs, areas, rural

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “These jobs are often located in rural or economically disadvantaged areas where wind farms and solar installations are built.”

Câu 10: climate change

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: small island nations, serious dangers, imported fuel

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Small island developing states, which face existential threats from climate change and often spend disproportionate amounts on imported diesel fuel.”

Câu 11: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: advantage, decentralized energy production

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “This decentralization of energy production means that natural disasters, political instability, or acts of terrorism in one region need not cripple a nation’s entire energy infrastructure.” Điều này cho thấy nó giảm vulnerability to regional disruptions.

Câu 12: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Germany’s energy transition

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “it has significantly reduced Germany’s dependence on Russian natural gas—a strategic vulnerability that became painfully apparent during recent geopolitical tensions.” Điều này cho thấy chính sách đã tiết lộ strategic weaknesses.

Câu 13: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: new security concern

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “the production of solar panels and batteries requires rare earth elements and other materials that are concentrated in a few countries, potentially creating new dependencies.”

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main reason, militaries, adopting renewable energy

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Armed forces worldwide are recognizing that energy efficiency and renewable power sources can provide tactical advantages, reduce logistical vulnerabilities.” Đây là lý do chính, không phải vì môi trường.

Câu 15: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: $400 per gallon

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “the cost of delivering fuel to forward operating bases can exceed $400 per gallon when accounting for transportation, security, and the risks to personnel.” Rõ ràng đây là total cost bao gồm delivery và security.

Câu 16: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: solar-powered UAVs, advantage

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “solar-powered unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can remain aloft for extended periods, providing persistent surveillance without the range limitations of fuel-powered aircraft.” “Remain aloft for extended periods” = stay airborne longer.

Câu 17: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: islanding

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “microgrids powered by renewable sources, which can continue operating even if disconnected from civilian power networks—a capability known as ‘islanding’.” Nghĩa là hoạt động độc lập khỏi mạng điện dân sự.

Câu 18: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: critics, argue

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Some analysts argue that the energy density of renewable sources remains insufficient for high-intensity combat operations.” Đây chính xác là lập luận của những người chỉ trích.

Câu 19: supply convoys

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: dangers, combat zones

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: “more than 3,000 American and allied troops and contractors were killed or wounded in attacks on fuel and water resupply convoys in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Câu 20: fuel resupply missions

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: reduce the need for

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Portable solar panels can power communications equipment, computers, and battery charging stations without requiring fuel resupply missions.”

Câu 21: acoustic signature

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: decrease, military positions, noisy generators

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “These systems not only decrease fuel requirements but also reduce the acoustic signature of military positions—diesel generators can be heard from considerable distances.”

Câu 22: biofuels

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: Naval forces, testing, algae and plants

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “The U.S. Navy has tested biofuels derived from algae and plant materials in its ships and aircraft.”

Câu 23: hybrid propulsion systems

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: combine, traditional engines, electric power

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “some navies are exploring hybrid propulsion systems that combine conventional engines with electric motors powered by solar panels and batteries.”

Câu 24: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: U.S. Department of Defense, largest institutional consumer, petroleum

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “The United States Department of Defense, for instance, is the world’s single largest institutional consumer of petroleum.” Câu này khẳng định DoD là tổ chức tiêu thụ nhiều dầu mỏ nhất.

Câu 25: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all military analysts agree, completely replace

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: Đoạn 8 cho thấy có critics không đồng ý (“Some analysts argue that the energy density of renewable sources remains insufficient”), và proponents chỉ nói về “incremental improvements” và “partial adoption”, không phải complete replacement.

Câu 26: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: artificial intelligence, future, military energy management

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “AI-driven predictive analytics could optimize energy usage across military installations, ensuring that renewable sources provide maximum benefit.” Tác giả rõ ràng khẳng định vai trò quan trọng của AI.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: renewable energy transition, comparable to

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “The global transition toward renewable energy sources represents not merely a technological evolution but a fundamental restructuring of international power dynamics that rivals in significance the shift from coal to oil in the early twentieth century.”

Câu 28: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: petrodollar system

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “The petrodollar system, whereby oil is predominantly traded in U.S. dollars, has reinforced American financial hegemony.” Định nghĩa rõ ràng về petrodollar system.

Câu 29: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: China, percentage, solar panels

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “China, which now produces approximately 70% of the world’s solar panels.” Con số 70% được nêu rõ ràng.

Câu 30: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Democratic Republic of Congo, significant

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “The Democratic Republic of Congo supplies approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt.” Đây là lý do Congo quan trọng trong địa chính trị năng lượng tái tạo.

Câu 31: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: potential benefit, international relations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 1-4

- Giải thích: “Some analysts argue that the diffuse nature of renewable energy resources, combined with decreased competition for concentrated fossil fuel reserves, could reduce interstate tensions and the likelihood of resource wars.”

Câu 32: asymmetric power relationships

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: unequal power relationships, producer and consumer

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Traditional energy geopolitics has been characterized by the concentration of fossil fuel resources in specific geographic regions, creating asymmetric power relationships between producer and consumer nations.”

Câu 33: Belt and Road Initiative

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: China’s, renewable energy projects, international influence

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “China’s Belt and Road Initiative increasingly incorporates renewable energy projects, extending Chinese influence through infrastructure development.”

Câu 34: energy sovereignty

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: meet energy requirements, domestic resources

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “the concept of ‘energy sovereignty’—the ability to meet energy needs from domestic resources—becomes more achievable.”

Câu 35: diffuse nature / decentralized character

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: renewable energy resources, reduce competition

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Some analysts argue that the diffuse nature of renewable energy resources, combined with decreased competition for concentrated fossil fuel reserves, could reduce interstate tensions.” Có thể chấp nhận cả hai đáp án vì đoạn văn dùng cả hai cụm từ với nghĩa tương tự.

Câu 36: distributed ledger technologies / blockchain

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: trade energy directly, without traditional utility companies

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Distributed ledger technologies could enable peer-to-peer energy trading that bypasses traditional utility structures.”

Câu 37: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: renewable energy resources, more evenly distributed, fossil fuels

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Unlike fossil fuels, renewable energy resources—solar radiation, wind, geothermal heat, and hydroelectric potential—are far more geographically dispersed and cannot be monopolized by a small number of states.” Tác giả rõ ràng khẳng định điều này.

Câu 38: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: European Union, exclusively from North Africa

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ nói “The European Union’s hydrogen strategy, which envisions importing renewable hydrogen from North Africa”, không đề cập đến việc nhập khẩu EXCLUSIVELY (chỉ duy nhất) từ Bắc Phi. Không đủ thông tin.

Câu 39: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: climate change, national security threat, renewable energy policy

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7

- Giải thích: “Climate change itself constitutes an increasingly significant national security threat that intersects with renewable energy considerations.” và “The renewable energy transition, by mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, addresses these security threats at their source.” Tác giả rõ ràng xác nhận mối liên hệ này.

Câu 40: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all analysts agree, definitely reduce international conflicts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nêu ra cả hai quan điểm: “Some analysts argue” về việc giảm xung đột, nhưng cũng có “counterarguments” cho rằng có thể tạo ra conflicts mới. Không phải tất cả các nhà phân tích đều đồng ý.

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| renewable energy | n | /rɪˈnjuːəbl ˈenədʒi/ | năng lượng tái tạo | renewable energy has moved from the margins of energy policy | renewable energy sources, renewable energy sector |

| geopolitical | adj | /ˌdʒiːoʊpəˈlɪtɪkl/ | thuộc về địa chính trị | enhance a nation’s geopolitical position | geopolitical tensions, geopolitical leverage |

| vulnerability | n | /ˌvʌlnərəˈbɪləti/ | tính dễ bị tổn thương | reduce their vulnerability to supply disruptions | strategic vulnerability, reduce vulnerability |

| over-reliance | n | /ˌoʊvərɪˈlaɪəns/ | sự phụ thuộc quá mức | the dangers of over-reliance on foreign energy sources | over-reliance on, avoid over-reliance |

| integration | n | /ˌɪntɪˈɡreɪʃn/ | sự hội nhập, tích hợp | one of the world’s leaders in renewable energy integration | energy integration, successful integration |

| export industry | n | /ˈekspɔːrt ˈɪndəstri/ | ngành công nghiệp xuất khẩu | created a thriving export industry for wind turbine technology | develop export industry, boost export industry |

| decentralization | n | /diːˌsentrəlaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | sự phân quyền, phi tập trung | This decentralization of energy production | energy decentralization, promote decentralization |

| grid modernization | n | /ɡrɪd ˌmɒdənaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | hiện đại hóa lưới điện | the need for grid modernization | require grid modernization, invest in grid modernization |

| economically disadvantaged | adj | /ˌiːkəˈnɒmɪkli ˌdɪsədˈvɑːntɪdʒd/ | thiệt thòi về kinh tế | in rural or economically disadvantaged areas | economically disadvantaged communities, support economically disadvantaged regions |

| technological capabilities | n | /ˌteknəˈlɒdʒɪkl ˌkeɪpəˈbɪlətiz/ | năng lực công nghệ | investment in renewable infrastructure creates technological capabilities | develop technological capabilities, enhance technological capabilities |

| existential threats | n | /ˌeɡzɪˈstenʃl θrets/ | mối đe dọa hiện hữu | face existential threats from climate change | pose existential threats, address existential threats |

| cybersecurity threats | n | /ˈsaɪbəsɪˌkjʊərəti θrets/ | mối đe dọa an ninh mạng | Cybersecurity threats to smart grids | mitigate cybersecurity threats, protect against cybersecurity threats |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paradigm shift | n | /ˈpærədaɪm ʃɪft/ | sự thay đổi mô hình tư duy | represents a paradigm shift in defense strategy | undergo paradigm shift, major paradigm shift |

| tactical advantages | n | /ˈtæktɪkl ədˈvɑːntɪdʒɪz/ | lợi thế chiến thuật | can provide tactical advantages | gain tactical advantages, significant tactical advantages |

| logistical vulnerabilities | n | /ləˈdʒɪstɪkl ˌvʌlnərəˈbɪlətiz/ | điểm yếu về hậu cần | reduce logistical vulnerabilities | expose logistical vulnerabilities, minimize logistical vulnerabilities |

| force projection | n | /fɔːrs prəˈdʒekʃn/ | khả năng triển khai lực lượng | fundamentally alter force projection capabilities | military force projection, enhance force projection |

| supply convoys | n | /səˈplaɪ ˈkɒnvɔɪz/ | đoàn xe tiếp tế | attacks on fuel and water resupply convoys | protect supply convoys, vulnerable supply convoys |

| logistical footprint | n | /ləˈdʒɪstɪkl ˈfʊtprɪnt/ | dấu chân hậu cần | reduce the logistical footprint of deployed forces | minimize logistical footprint, reduce logistical footprint |

| acoustic signature | n | /əˈkuːstɪk ˈsɪɡnətʃər/ | dấu hiệu âm thanh | reduce the acoustic signature of military positions | detectable acoustic signature, minimize acoustic signature |

| microgrids | n | /ˈmaɪkrəʊɡrɪdz/ | lưới điện vi mô | Many military installations are exploring microgrids | deploy microgrids, renewable microgrids |

| islanding | n | /ˈaɪləndɪŋ/ | khả năng hoạt động độc lập | a capability known as islanding | islanding capability, achieve islanding |

| resilience | n | /rɪˈzɪliəns/ | tính kiên cường, khả năng phục hồi | This resilience is crucial for maintaining operational readiness | build resilience, enhance resilience |

| geothermal energy | n | /ˌdʒiːoʊˈθɜːrml ˈenədʒi/ | năng lượng địa nhiệt | has implemented a geothermal energy system | harness geothermal energy, geothermal energy potential |

| biofuels | n | /ˈbaɪoʊfjuːəlz/ | nhiên liệu sinh học | The U.S. Navy has tested biofuels derived from algae | produce biofuels, sustainable biofuels |

| hybrid propulsion | n | /ˈhaɪbrɪd prəˈpʌlʃn/ | hệ thống đẩy lai | exploring hybrid propulsion systems | hybrid propulsion technology, implement hybrid propulsion |

| geopolitical ramifications | n | /ˌdʒiːoʊpəˈlɪtɪkl ˌræmɪfɪˈkeɪʃnz/ | hậu quả địa chính trị | The geopolitical ramifications deserve careful consideration | significant geopolitical ramifications, consider geopolitical ramifications |

| strategic leverage | n | /strəˈtiːdʒɪk ˈlevərɪdʒ/ | đòn bẩy chiến lược | may find their strategic leverage diminished | maintain strategic leverage, gain strategic leverage |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| recalibrating | v | /ˌriːˈkæləbreɪtɪŋ/ | hiệu chỉnh lại | is recalibrating the balance of geopolitical influence | recalibrate strategy, recalibrate approach |

| unprecedented | adj | /ʌnˈpresɪdentɪd/ | chưa từng có | potential for unprecedented international cooperation | unprecedented scale, unprecedented opportunity |

| asymmetric power | n | /ˌeɪsɪˈmetrɪk ˈpaʊər/ | quyền lực bất đối xứng | creating asymmetric power relationships | asymmetric power dynamics, exploit asymmetric power |

| structural dependence | n | /ˈstrʌktʃərəl dɪˈpendəns/ | sự phụ thuộc cơ cấu | This structural dependence has driven foreign policy | reduce structural dependence, create structural dependence |

| superseded | v | /ˌsuːpərˈsiːdɪd/ | thay thế, lấn át | energy security considerations often superseded other policy priorities | supersede traditional methods, supersede previous policies |

| democratization | n | /dɪˌmɒkrətaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | dân chủ hóa | This democratization of energy could reduce geopolitical significance | energy democratization, promote democratization |

| geographically dispersed | adj | /ˌdʒiːəˈɡræfɪkli dɪˈspɜːrst/ | phân tán về mặt địa lý | renewable energy resources are far more geographically dispersed | geographically dispersed resources, widely geographically dispersed |

| confers strategic advantages | v phrase | /kənˈfɜːrz strəˈtiːdʒɪk ədˈvɑːntɪdʒɪz/ | mang lại lợi thế chiến lược | This concentration confers strategic advantages | confer benefits, confer authority |

| leverage dominance | v phrase | /ˈlevərɪdʒ ˈdɒmɪnəns/ | tận dụng sự thống trị | China could potentially leverage its dominance | leverage position, leverage resources |

| critical minerals | n | /ˈkrɪtɪkl ˈmɪnərəlz/ | khoáng sản quan trọng | Critical mineral supplies represent perhaps the most significant new vulnerability | secure critical minerals, critical minerals supply chain |

| unevenly distributed | adj | /ʌnˈiːvnli dɪˈstrɪbjuːtɪd/ | phân bố không đều | are unevenly distributed globally | unevenly distributed resources, unevenly distributed wealth |

| strategic chokepoints | n | /strəˈtiːdʒɪk ˈtʃoʊkpɔɪnts/ | điểm nghẽn chiến lược | This concentration creates strategic chokepoints | control strategic chokepoints, vulnerable strategic chokepoints |

| recapitulating | v | /ˌriːkəˈpɪtʃuleɪtɪŋ/ | tái diễn, lặp lại | recapitulating, in new form, the resource dependencies | recapitulate arguments, recapitulate historical patterns |

| energy sovereignty | n | /ˈenədʒi ˈsɒvrənti/ | chủ quyền năng lượng | the concept of energy sovereignty becomes more achievable | achieve energy sovereignty, protect energy sovereignty |

| intersects with | v phrase | /ˌɪntərˈsekts wɪð/ | giao thoa với | climate change itself constitutes a threat that intersects with renewable energy | intersect with policy, intersect with interests |

| greenhouse gas emissions | n | /ˈɡriːnhaʊs ɡæs ɪˈmɪʃnz/ | khí thải nhà kính | by mitigating greenhouse gas emissions | reduce greenhouse gas emissions, monitor greenhouse gas emissions |

| interstate tensions | n | /ˌɪntərˈsteɪt ˈtenʃnz/ | căng thẳng giữa các quốc gia | could reduce interstate tensions and the likelihood of resource wars | escalate interstate tensions, ease interstate tensions |

| historical inflection point | n | /hɪˈstɒrɪkl ɪnˈflekʃn pɔɪnt/ | điểm uốn lịch sử | represents a historical inflection point in international relations | reach inflection point, critical inflection point |

Học viên đang luyện tập IELTS Reading với đề thi về năng lượng tái tạo và an ninh quốc gia

Học viên đang luyện tập IELTS Reading với đề thi về năng lượng tái tạo và an ninh quốc gia

Kết Bài

Qua bài viết này, bạn đã được tiếp cận với một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh về chủ đề năng lượng tái tạo và ảnh hưởng của nó đến các chiến lược an ninh quốc gia. Đây là một chủ đề vô cùng quan trọng và thường xuyên xuất hiện trong các kỳ thi IELTS Academic, đòi hỏi người học không chỉ có kỹ năng đọc hiểu mà còn phải nắm vững từ vựng học thuật chuyên ngành.

Ba passages trong đề thi này được thiết kế với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, hoàn toàn giống với format thi thật. Passage 1 giúp bạn làm quen với chủ đề và các khái niệm cơ bản, Passage 2 đi sâu vào ứng dụng quân sự với độ phức tạp trung bình, và Passage 3 phân tích các tác động địa chính trị sâu sắc với ngôn ngữ học thuật cao cấp.

Đáp án chi tiết kèm theo giải thích cụ thể cho từng câu sẽ giúp bạn hiểu rõ tại sao một đáp án đúng và cách xác định thông tin trong bài đọc. Đặc biệt, phần từ vựng được tổng hợp theo từng passage với phonetic, nghĩa tiếng Việt và collocations sẽ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ vựng học thuật một cách hệ thống.

Hãy dành thời gian luyện tập với đề thi này nhiều lần, phân tích kỹ các kỹ thuật làm bài và ghi nhớ từ vựng. Đừng quên áp dụng các chiến lược quản lý thời gian được đề xuất để đạt kết quả tốt nhất trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading của bạn.

[…] to discussions around how is renewable energy influencing national security strategies?, the geopolitical dimensions of blockchain in trade are increasingly evident. Control over key […]