Mở bài

Chủ đề giáo dục hòa nhập (inclusive education) đang trở thành một trong những xu hướng quan trọng nhất trong hệ thống giáo dục toàn cầu, và cũng là một chủ đề phổ biến trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Với sự đa dạng ngày càng tăng trong các lớp học hiện đại, việc thúc đẩy môi trường học đường hòa nhập không chỉ là trách nhiệm đạo đức mà còn là yếu tố then chốt quyết định chất lượng giáo dục.

Bài viết này cung cấp một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với ba passages từ dễ đến khó, giúp bạn làm quen với nhiều khía cạnh khác nhau của chủ đề giáo dục hòa nhập. Bạn sẽ được trải nghiệm đầy đủ các dạng câu hỏi thường gặp trong kỳ thi thật, từ Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given đến Matching Headings và Summary Completion. Mỗi passage đi kèm với đáp án chi tiết và giải thích cụ thể, giúp bạn hiểu rõ phương pháp tiếp cận và kỹ thuật paraphrase quan trọng trong IELTS Reading.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, với độ khó tăng dần qua ba passages, phản ánh chính xác cấu trúc của bài thi IELTS thực tế. Hãy chuẩn bị đồng hồ, tìm một không gian yên tĩnh và bắt đầu luyện tập như đang trong phòng thi thật!

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, và band score cuối cùng được quy đổi dựa trên tổng số câu đúng. Điểm đặc biệt quan trọng là bạn phải tự quản lý thời gian vì không có thời gian riêng để chuyển đáp án sang phiếu trả lời.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó thấp nhất, nên làm nhanh để dành thời gian cho passages sau)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình, cần đọc kỹ hơn)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao nhất, yêu cầu phân tích sâu)

Lưu ý quan trọng: Đọc kỹ instructions của mỗi dạng câu hỏi, đặc biệt chú ý giới hạn số từ khi điền đáp án (ví dụ: “NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS”).

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice: Chọn đáp án đúng từ các phương án cho sẵn

- True/False/Not Given: Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hoặc không được đề cập

- Yes/No/Not Given: Xác định ý kiến của tác giả

- Matching Headings: Ghép tiêu đề phù hợp cho mỗi đoạn văn

- Summary Completion: Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features: Ghép thông tin với đặc điểm tương ứng

- Short-answer Questions: Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn với số từ giới hạn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Building Blocks of an Inclusive Classroom

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Creating an inclusive classroom environment is one of the most important challenges facing modern educators. Inclusivity in schools refers to the practice of ensuring that all students, regardless of their backgrounds, abilities, or learning styles, feel welcomed, respected, and supported in their educational journey. This approach goes beyond simply placing students with different needs in the same classroom; it requires a fundamental shift in teaching philosophy and classroom management.

The foundation of an inclusive classroom begins with the physical environment. Teachers should arrange furniture and learning spaces to accommodate students with various needs. For example, wheelchair-accessible pathways, adjustable desks, and quiet zones for students who need reduced sensory stimulation are essential features. Visual aids, such as picture schedules and color-coded materials, help students with learning disabilities or those learning in a second language understand classroom routines and expectations more easily.

Curriculum adaptation plays a crucial role in fostering inclusivity. Rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach, effective teachers differentiate instruction to meet diverse learning needs. This might involve presenting information through multiple formats – visual, auditory, and kinesthetic – to engage different types of learners. For instance, when teaching a history lesson, an inclusive teacher might combine traditional lectures with videos, hands-on activities, and group discussions. This multi-modal approach ensures that students with different strengths and preferences can access the same content in ways that work best for them.

Building positive relationships is another cornerstone of inclusive education. Teachers should take time to learn about each student’s cultural background, interests, and individual needs. This knowledge allows educators to create lessons that reflect the diversity of their classroom and help all students see themselves represented in the curriculum. When students from minority backgrounds see their cultures and experiences reflected in what they learn, they develop a stronger sense of belonging and engagement with their education.

Peer relationships are equally important in creating an inclusive atmosphere. Teachers can facilitate positive interactions through cooperative learning activities that require students to work together toward common goals. These activities should be carefully structured to ensure that all students can contribute meaningfully, regardless of their ability levels. For example, in a group project, roles can be assigned based on individual strengths – one student might excel at research, another at artistic presentation, and another at oral communication.

Language choice matters significantly in inclusive classrooms. Teachers should use person-first language that puts the individual before any disability or difference. Instead of saying “disabled student,” educators should say “student with a disability.” This seemingly small change reflects a fundamental respect for the person’s identity beyond their challenges. Similarly, teachers should be mindful of avoiding stereotypes and generalizations about any group of students, whether based on ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, or learning differences.

Professional development for teachers is essential to successful inclusion. Many educators receive limited training in inclusive practices during their initial teacher education. Schools should provide ongoing workshops and training sessions that help teachers develop skills in differentiated instruction, behavior management for diverse classrooms, and strategies for supporting students with specific needs. Teachers who feel confident and prepared are more likely to implement inclusive practices effectively.

Family involvement strengthens inclusive education efforts. Schools should actively engage families from all backgrounds in their children’s education, recognizing that families are experts on their own children. This might involve providing materials in multiple languages, scheduling meetings at times that work for working parents, or offering different formats for parent-teacher conferences – in person, by phone, or through video calls. When families feel welcomed and valued, they become partners in creating an inclusive school community.

Finally, school leaders play a critical role in fostering inclusivity. Principals and administrators set the tone by articulating clear values about diversity and inclusion, allocating resources to support inclusive practices, and holding staff accountable for creating welcoming environments. When school leadership prioritizes inclusion, it sends a powerful message to students, families, and the broader community that every student matters and deserves quality education.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, inclusivity in schools means

A. placing students with special needs in separate classrooms

B. treating all students exactly the same way

C. ensuring all students feel welcomed and supported

D. focusing only on students with disabilities -

The physical environment of an inclusive classroom should include

A. only traditional desk arrangements

B. features that accommodate various student needs

C. the same setup for every classroom

D. minimal visual aids -

Differentiated instruction involves

A. teaching every student the same way

B. presenting information through multiple formats

C. focusing only on visual learners

D. avoiding technology in the classroom -

According to the passage, person-first language

A. is not important in inclusive classrooms

B. focuses on disabilities before the person

C. puts the individual before any disability

D. should only be used with parents -

The passage suggests that school leaders foster inclusivity by

A. leaving decisions to individual teachers

B. focusing only on academic achievement

C. articulating clear values about diversity

D. avoiding difficult conversations about inclusion

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Write TRUE if the statement agrees with the information, FALSE if the statement contradicts the information, or NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this.

- Color-coded materials can help students learning in a second language understand classroom routines.

- Most teachers receive comprehensive training in inclusive practices during their initial education.

- Parent-teacher conferences should only be conducted in person.

- Cooperative learning activities should ensure all students can contribute meaningfully.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- Teachers should learn about each student’s cultural background and __ to create inclusive lessons.

- When students from minority backgrounds see their cultures reflected in lessons, they develop a stronger sense of __.

- Schools should provide materials in __ to engage families from diverse backgrounds.

- Effective teachers use a __ approach that includes visual, auditory, and kinesthetic methods.

PASSAGE 2 – The Psychology Behind Inclusive School Communities

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The psychological foundations of inclusive education extend far beyond simple tolerance or accommodation of differences. Research in educational psychology and social neuroscience reveals that truly inclusive school environments fundamentally reshape how students perceive themselves, their peers, and their capacity for learning. Understanding these underlying mechanisms provides educators with powerful insights into why certain inclusive practices succeed while others fail to achieve their intended outcomes.

At the heart of inclusive education lies the concept of belonging, a fundamental human need that ranks alongside physical safety and sustenance in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. When students experience a genuine sense of belonging, their brains release neurochemicals such as oxytocin and dopamine, which enhance cognitive function, memory consolidation, and emotional regulation. Conversely, experiences of exclusion or marginalization trigger stress responses that impair learning by redirecting neural resources away from higher-order thinking toward threat detection and self-protection. This neurobiological reality explains why even academically capable students underperform when they feel they don’t belong in their school community.

Social identity theory, developed by psychologist Henri Tajfel, provides another lens through which to understand inclusive education’s importance. This theory posits that individuals derive significant aspects of their self-concept from the groups to which they belong. In school settings, students constantly negotiate multiple identities – academic, social, cultural, and personal. When schools validate and celebrate diverse identities rather than privileging certain backgrounds over others, students develop more robust and positive self-concepts. This psychological foundation supports academic resilience, the ability to persevere through challenges and setbacks.

The concept of stereotype threat, extensively researched by Claude Steele and his colleagues, illuminates how subtle messages about group abilities can sabotage student performance. When students are aware of negative stereotypes about their social group – whether based on ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, or learning differences – they may inadvertently fulfill these stereotypes through impaired performance caused by anxiety and hyper-vigilance. Inclusive schools actively work to counteract stereotype threat by creating environments where multiple forms of excellence are recognized and where counter-stereotypical examples are readily visible. For instance, highlighting diverse role models in science helps combat stereotypes about who can succeed in STEM fields.

Growth mindset theory, pioneered by psychologist Carol Dweck, intersects powerfully with inclusive education practices. Students with growth mindsets believe that abilities can be developed through effort and effective strategies, rather than being fixed traits. Inclusive classrooms naturally foster growth mindsets by emphasizing multiple paths to learning and success. When students see peers with different abilities all making progress through various approaches, they internalize the message that struggle is a normal part of learning, not a sign of inadequacy. This psychological shift is particularly important for students who have historically been told, explicitly or implicitly, that they lack certain capacities.

Điều này có điểm tương đồng với digital leadership programs for young learners khi cả hai đều tập trung vào phát triển tư duy phản biện và kỹ năng thích ứng trong môi trường đa dạng.

Intergroup contact theory, formulated by Gordon Allport in the 1950s, remains highly relevant to contemporary inclusive education. This theory suggests that prejudice and intergroup tensions can be reduced through positive contact between members of different groups, provided certain conditions are met: equal status within the situation, common goals, intergroup cooperation, and support from authorities. Inclusive classrooms that implement cooperative learning structures meeting these conditions become laboratories for developing cross-cultural competence and dismantling stereotypes. Students who regularly work collaboratively with diverse peers develop more nuanced understandings of individual differences and are less likely to rely on simplistic categorizations.

The self-determination theory developed by Deci and Ryan offers additional insights into inclusive education’s psychological benefits. This theory identifies three basic psychological needs – autonomy, competence, and relatedness – that must be satisfied for optimal human functioning. Inclusive classrooms address all three needs simultaneously. Student choice in learning activities promotes autonomy; differentiated instruction ensures that all students can experience competence at appropriate challenge levels; and the emphasis on community and connection satisfies the need for relatedness. When these needs are met, students experience intrinsic motivation, the most powerful and sustainable form of learning drive.

Empathy development represents another crucial psychological outcome of inclusive education. Neuroscientific research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) shows that the brain’s empathy networks – including the anterior cingulate cortex and insula – become more active and developed through regular exposure to diverse perspectives and experiences. Students in inclusive classrooms have daily opportunities to take the perspective of peers whose experiences differ from their own, whether those differences relate to learning styles, cultural backgrounds, or physical abilities. This empathic capacity serves students well beyond school, preparing them for citizenship in increasingly diverse societies and workplaces.

Finally, inclusive education contributes to what psychologists call psychological flexibility – the ability to adapt one’s thinking and behavior to meet varied demands of different situations. Students in inclusive environments regularly encounter ambiguity and complexity as they navigate interactions with diverse peers and engage with multiple perspectives. Rather than seeking single “right” answers, they learn to appreciate nuance and contextual factors. This cognitive flexibility is increasingly recognized as essential for success in the 21st century, where rapid change and diverse collaboration are the norm rather than the exception.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in the passage? Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Simple tolerance of differences is sufficient to create truly inclusive school environments.

- Experiences of exclusion can impair students’ cognitive abilities by triggering stress responses.

- Social identity theory was developed more recently than stereotype threat research.

- Growth mindset theory suggests that abilities are fixed traits that cannot be changed.

- Students in inclusive classrooms develop better empathy skills than those in traditional settings.

Questions 19-23: Matching Headings

Choose the correct heading for each section from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. The role of brain chemistry in learning

ii. Historical perspectives on educational inclusion

iii. Multiple paths to developing student confidence

iv. How group membership affects self-perception

v. The dangers of negative expectations

vi. Meeting fundamental psychological needs

vii. Reducing prejudice through structured interaction

viii. The importance of teacher training

- Paragraph discussing social identity theory (Paragraph 3)

- Paragraph discussing stereotype threat (Paragraph 4)

- Paragraph discussing growth mindset theory (Paragraph 5)

- Paragraph discussing intergroup contact theory (Paragraph 6)

- Paragraph discussing self-determination theory (Paragraph 7)

Questions 24-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Inclusive education is grounded in strong psychological principles. The concept of (24) __ is a fundamental human need that affects brain chemistry and learning capacity. Research shows that when students feel excluded, their brains redirect resources toward (25) __ instead of higher-order thinking. Additionally, inclusive classrooms help develop (26) __, which is the ability to adapt thinking and behavior to different situations.

PASSAGE 3 – Systemic Transformation: Implementing Inclusive Education at Scale

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The transition from segregated or mainstream educational models to genuinely inclusive systems represents one of the most profound and complex transformations facing contemporary education. While the moral and pedagogical imperatives for inclusive education are increasingly well-established, the practical mechanisms through which school systems can achieve this transformation at scale remain subject to considerable debate and empirical investigation. Understanding the multi-layered challenges and strategic interventions necessary for systemic change requires analyzing experiences from diverse educational contexts worldwide, as well as engaging with theoretical frameworks from organizational change management, implementation science, and systems thinking.

Institutional resistance to inclusive education often manifests not through explicit opposition but through subtle mechanisms of organizational inertia and path dependence. Educational institutions are characterized by what organizational theorists term deeply embedded routines and normative structures that resist reconfiguration, even when stakeholders ostensibly support change. Traditional school architectures – both physical and organizational – were designed around assumptions of student homogeneity and hierarchical ability tracking. Dismantling these structures requires not merely policy directives but fundamental reconceptualization of school organization, teacher roles, and success metrics. Research by Fullan and Quinn on coherence-making emphasizes that successful educational transformation demands alignment across multiple system levels: individual mindsets, collaborative practices, organizational structures, and system-level policies must all move in complementary directions to achieve sustainable change.

Resource allocation presents both practical and ideological challenges to inclusive education implementation. Opponents of inclusion frequently cite budgetary constraints, arguing that supporting diverse learners in general education classrooms is prohibitively expensive. However, longitudinal economic analyses by researchers including Ruijs and Peetsma demonstrate that inclusive systems can achieve cost-effectiveness over time by reducing duplication of services, minimizing administrative overhead of separate programs, and decreasing long-term social costs associated with educational segregation. The initial investment required for inclusive education – including teacher training, curriculum development, and physical accessibility modifications – should be understood as infrastructure development comparable to other essential educational modernization efforts. Reframing the economic discussion from short-term costs to long-term value requires sophisticated advocacy and presentation of longitudinal data demonstrating inclusive education’s return on investment.

Một ví dụ chi tiết về the role of education in fostering global cultural exchange cho thấy cách các hệ thống giáo dục toàn cầu đang chuyển đổi để đáp ứng nhu cầu đa dạng của học sinh trong thế kỷ 21.

Teacher preparation and professional learning represent critical leverage points for systemic change, yet current approaches often prove inadequate to the task. Traditional pre-service teacher education programs typically offer limited, decontextualized coursework on inclusive practices, failing to develop the sophisticated pedagogical repertoires teachers need. Research by Florian and Spratt on the inclusive pedagogical approach suggests that effective teacher preparation must move beyond deficit-oriented models that focus on identifying and accommodating student “problems” toward capacity-building approaches that develop teachers’ skills in creating learning environments rich enough to serve diverse needs. This requires reconceptualizing teacher expertise from knowledge of specialized techniques for different “categories” of students toward adaptive expertise – the ability to innovate and improvise effectively when faced with novel teaching challenges. Achieving this shift demands extensive practice-based learning opportunities where teachers can experiment with inclusive approaches, receive nuanced feedback, and engage in collaborative reflection on their practice.

Assessment and accountability systems often create perverse incentives that undermine inclusive education, even in jurisdictions with ostensibly pro-inclusive policies. When school and teacher evaluations rely heavily on standardized test scores, particularly those reported by demographic subgroups, schools face pressure to exclude students likely to score poorly. Research by Darling-Hammond and Adamson on international assessment systems reveals that jurisdictions achieving both excellence and equity – notably Finland and certain Canadian provinces – employ multidimensional accountability frameworks that balance academic indicators with measures of student well-being, engagement, and social-emotional development. These systems also typically use assessment results formatively to identify improvement areas rather than punitively to sanction schools. Transforming accountability systems to support rather than impede inclusion requires fundamental reconceptualization of educational quality and success, moving beyond narrow academic metrics to embrace holistic conceptions of student development and school effectiveness.

Community engagement and cultural change dimensions of inclusive education implementation are frequently underestimated. Schools are embedded in broader communities with their own histories, values, and power dynamics. In many contexts, deeply entrenched beliefs about ability, difference, and educational entitlement create resistance to inclusion. Socioeconomically advantaged families may view inclusive education as threatening their children’s educational advantages, while families of students with disabilities may have ambivalent feelings about inclusion based on previous negative experiences in general education settings. Effective community engagement strategies, as documented by researchers including Ainscow and Sandill, move beyond superficial consultation toward genuine partnership in envisioning and implementing inclusive schools. This involves creating multiple access points for diverse voices, particularly those historically marginalized from educational decision-making, and demonstrating through pilot programs and transparent communication how inclusive education benefits all students. The iterative process of community dialogue, experimentation, and adaptation helps build the collective ownership necessary for sustained implementation.

Technology presents both opportunities and risks for advancing inclusive education at scale. Assistive technologies and universal design for learning (UDL) principles offer unprecedented possibilities for customizing learning experiences to diverse needs. Digital platforms can provide multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement, key tenets of UDL that support diverse learners. However, uncritical technology adoption risks exacerbating rather than ameliorating educational inequities. The “digital divide” encompasses not only access to devices and connectivity but also disparities in digital literacy, technical support, and the quality of educational software available to different students. Moreover, algorithmic sorting and adaptive learning systems may inadvertently reproduce traditional tracking if they channel students into differentiated pathways based on initial assessments. Research by Reich and Ito on technology and educational equity emphasizes that realizing technology’s inclusive potential requires intentional design, equitable implementation, and ongoing critical examination of how digital tools affect diverse learners.

The temporal dimensions of inclusive education transformation are frequently misconstrued. Policy-makers and reformers often seek rapid implementation, while research on educational change suggests that deep, sustainable transformation typically requires extended timeframes – often a decade or more. Hargreaves and Fullan’s work on professional capital emphasizes that developing the collective capacity for inclusive education demands patient investment in building human capital (individual knowledge and skills), social capital (collaborative relationships and networks), and decisional capital (professional judgment refined through experience). Premature scaling of inclusive initiatives before sufficient capacity development often results in superficial implementation that discredits the inclusive education concept itself. Conversely, indefinite pilot programs never reaching scale also fail to achieve transformation. Navigating this tension requires strategic sequencing that balances urgency with developmental readiness, expanding implementation as capacity develops rather than according to arbitrary timelines.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, institutional resistance to inclusive education primarily occurs through

A. explicit opposition from teachers

B. student protests

C. organizational inertia and embedded routines

D. lack of government funding -

The passage suggests that successful educational transformation requires

A. focusing only on policy changes

B. alignment across multiple system levels

C. rapid implementation within one year

D. minimal financial investment -

Longitudinal economic analyses demonstrate that inclusive education

A. is always more expensive than segregated systems

B. cannot achieve cost-effectiveness

C. can achieve cost-effectiveness over time

D. should not be evaluated economically -

According to Florian and Spratt, effective teacher preparation should focus on

A. memorizing specialized techniques for each disability

B. identifying student problems

C. traditional coursework only

D. developing adaptive expertise -

The passage indicates that assessment and accountability systems often

A. always support inclusive education

B. create incentives that undermine inclusion

C. have no impact on school practices

D. focus exclusively on student well-being

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each research finding (A-H) with the correct researcher or researchers (32-36).

List of Researchers:

32. Fullan and Quinn

33. Ruijs and Peetsma

34. Darling-Hammond and Adamson

35. Ainscow and Sandill

36. Reich and Ito

Research Findings:

A. Examined how technology can affect educational equity

B. Studied effective community engagement strategies

C. Analyzed international assessment systems

D. Researched patient investment in professional capital

E. Demonstrated cost-effectiveness of inclusive systems

F. Emphasized coherence-making in educational transformation

G. Developed universal design for learning principles

H. Studied segregated education exclusively

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

- What type of expertise do teachers need to innovate effectively when facing novel teaching challenges?

- What two words describe the type of accountability frameworks used in Finland and certain Canadian provinces?

- According to the passage, what encompasses not only access to devices but also disparities in digital literacy?

- How long does deep, sustainable educational transformation typically require according to research on educational change?

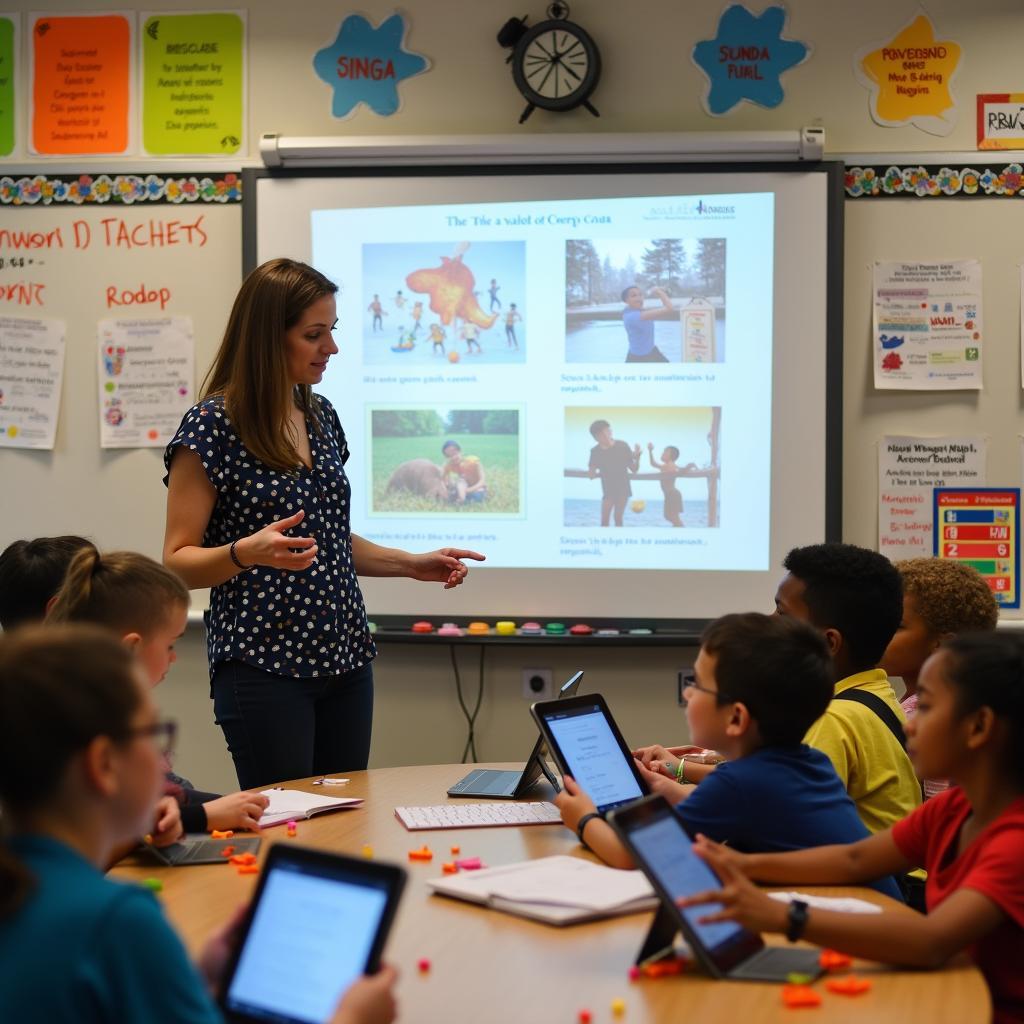

Học sinh đa dạng cùng học trong lớp học hòa nhập hiện đại với công nghệ hỗ trợ

Học sinh đa dạng cùng học trong lớp học hòa nhập hiện đại với công nghệ hỗ trợ

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- C

- B

- B

- C

- C

- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- individual needs

- belonging

- multiple languages

- multi-modal

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- NO

- YES

- iv

- v

- iii

- vii

- vi

- belonging

- threat detection

- psychological flexibility

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- C

- B

- C

- D

- B

- F

- E

- C

- B

- A

- adaptive expertise

- multidimensional accountability

- digital divide

- a decade (hoặc: extended timeframes)

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: inclusivity in schools means

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “Inclusivity in schools refers to the practice of ensuring that all students, regardless of their backgrounds, abilities, or learning styles, feel welcomed, respected, and supported in their educational journey.” Đây là paraphrase trực tiếp của đáp án C. Các đáp án khác sai vì: A đề cập đến “placing students in separate classrooms” – điều bài đọc phủ định; B nói về “treating all students exactly the same way” – không phải là inclusivity; D chỉ tập trung vào “students with disabilities” – quá hẹp.

Câu 2: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: physical environment, inclusive classroom

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn mô tả “wheelchair-accessible pathways, adjustable desks, and quiet zones” là các tính năng cần thiết, tương ứng với “features that accommodate various student needs” trong đáp án B.

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: color-coded materials, second language

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “Visual aids, such as picture schedules and color-coded materials, help students with learning disabilities or those learning in a second language understand classroom routines” – khớp hoàn toàn với câu hỏi.

Câu 7: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: teachers receive comprehensive training

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “Many educators receive limited training in inclusive practices during their initial teacher education” – trái ngược hoàn toàn với “comprehensive training” trong câu hỏi.

Câu 10: individual needs

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: cultural background

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Câu gốc: “Teachers should take time to learn about each student’s cultural background, interests, and individual needs.” Đáp án phải là “individual needs” để hoàn thành câu đúng ngữ pháp và nghĩa.

Câu 13: multi-modal

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: visual, auditory, kinesthetic

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 7-8

- Giải thích: Bài đọc đề cập “This multi-modal approach ensures that students with different strengths and preferences can access the same content” sau khi liệt kê các phương pháp visual, auditory, kinesthetic.

Giáo viên áp dụng phương pháp giảng dạy đa dạng trong lớp học hòa nhập với nhiều hoạt động

Giáo viên áp dụng phương pháp giảng dạy đa dạng trong lớp học hòa nhập với nhiều hoạt động

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: simple tolerance sufficient

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài đọc mở đầu bằng “The psychological foundations of inclusive education extend far beyond simple tolerance or accommodation of differences” – rõ ràng phủ định quan điểm rằng tolerance đơn giản là đủ.

Câu 15: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: exclusion, impair, cognitive abilities, stress

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “experiences of exclusion or marginalization trigger stress responses that impair learning by redirecting neural resources away from higher-order thinking” – hoàn toàn khớp với quan điểm trong câu hỏi.

Câu 19: iv

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Từ khóa: social identity theory

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: Heading iv “How group membership affects self-perception” chính xác tóm tắt nội dung đoạn văn về social identity theory, nơi đề cập “individuals derive significant aspects of their self-concept from the groups to which they belong.”

Câu 20: v

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Từ khóa: stereotype threat

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: Heading v “The dangers of negative expectations” phản ánh chính xác nội dung về stereotype threat, đặc biệt là phần nói về “negative stereotypes” và “impaired performance caused by anxiety.”

Câu 24: belonging

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: fundamental human need

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “At the heart of inclusive education lies the concept of belonging, a fundamental human need” – đáp án phải là “belonging.”

Câu 26: psychological flexibility

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: ability to adapt thinking and behavior

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn cuối, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài đọc định nghĩa “psychological flexibility – the ability to adapt one’s thinking and behavior to meet varied demands of different situations” – khớp chính xác với mô tả trong summary.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: institutional resistance primarily occurs

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc giải thích “Institutional resistance to inclusive education often manifests not through explicit opposition but through subtle mechanisms of organizational inertia and path dependence” và “deeply embedded routines” – đáp án C tóm tắt chính xác điều này.

Câu 28: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: successful educational transformation requires

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 8-10

- Giải thích: Bài đọc trích dẫn nghiên cứu của Fullan và Quinn về “coherence-making emphasizes that successful educational transformation demands alignment across multiple system levels” – đáp án B paraphrase trực tiếp.

Câu 29: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: longitudinal economic analyses

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “longitudinal economic analyses by researchers including Ruijs and Peetsma demonstrate that inclusive systems can achieve cost-effectiveness over time” – đáp án C chính xác.

Câu 32: F

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Từ khóa: Fullan and Quinn

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 8-10

- Giải thích: Bài đọc đề cập “Research by Fullan and Quinn on coherence-making emphasizes…” – khớp với finding F về “coherence-making in educational transformation.”

Câu 37: adaptive expertise

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: teachers need, innovate, novel teaching challenges

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 7-9

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “This requires reconceptualizing teacher expertise from knowledge of specialized techniques… toward adaptive expertise – the ability to innovate and improvise effectively when faced with novel teaching challenges.”

Câu 38: multidimensional accountability

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: frameworks, Finland, Canadian provinces

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài đọc đề cập “jurisdictions achieving both excellence and equity – notably Finland and certain Canadian provinces – employ multidimensional accountability frameworks.”

Câu 40: a decade / extended timeframes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: deep sustainable transformation typically require

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “research on educational change suggests that deep, sustainable transformation typically requires extended timeframes – often a decade or more.” Cả hai đáp án đều chấp nhận được.

Buổi họp phụ huynh và giáo viên bàn về giáo dục hòa nhập tại trường học

Buổi họp phụ huynh và giáo viên bàn về giáo dục hòa nhập tại trường học

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inclusivity | n | /ˌɪnkluːˈsɪvəti/ | tính hòa nhập, bao gồm | “Inclusivity in schools refers to the practice…” | foster inclusivity, promote inclusivity |

| accommodate | v | /əˈkɒmədeɪt/ | điều chỉnh để phù hợp, chứa đựng | “Teachers should arrange furniture to accommodate students” | accommodate needs, accommodate diversity |

| differentiate | v | /ˌdɪfəˈrenʃieɪt/ | phân biệt, điều chỉnh khác nhau | “effective teachers differentiate instruction” | differentiate instruction, differentiate curriculum |

| kinesthetic | adj | /ˌkɪnɪsˈθetɪk/ | liên quan đến vận động | “visual, auditory, and kinesthetic” | kinesthetic learning, kinesthetic activities |

| cornerstone | n | /ˈkɔːnəstəʊn/ | nền tảng, điều cốt lõi | “Building positive relationships is another cornerstone” | cornerstone of education, key cornerstone |

| peer relationships | n | /pɪə rɪˈleɪʃənʃɪps/ | quan hệ bạn bè, đồng trang lứa | “Peer relationships are equally important” | develop peer relationships, positive peer relationships |

| person-first language | n | /ˈpɜːsn fɜːst ˈlæŋɡwɪdʒ/ | ngôn ngữ đặt con người lên đầu | “Teachers should use person-first language” | use person-first language, adopt person-first language |

| stereotype | n | /ˈsteriətaɪp/ | khuôn mẫu, định kiến | “avoiding stereotypes and generalizations” | avoid stereotypes, challenge stereotypes |

| professional development | n | /prəˈfeʃənl dɪˈveləpmənt/ | phát triển chuyên môn | “Professional development for teachers is essential” | ongoing professional development, teacher professional development |

| articulate | v | /ɑːˈtɪkjuleɪt/ | diễn đạt rõ ràng | “articulating clear values about diversity” | articulate values, articulate vision |

| engage families | v phrase | /ɪnˈɡeɪdʒ ˈfæməliz/ | thu hút sự tham gia của gia đình | “Schools should actively engage families” | engage families effectively, meaningfully engage families |

| multi-modal | adj | /ˈmʌlti ˈməʊdl/ | đa phương thức | “This multi-modal approach ensures…” | multi-modal approach, multi-modal instruction |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| neurobiological | adj | /ˌnjʊərəʊbaɪəˈlɒdʒɪkl/ | liên quan đến thần kinh sinh học | “This neurobiological reality explains…” | neurobiological mechanisms, neurobiological factors |

| marginalization | n | /ˌmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | sự đẩy ra ngoài lề | “experiences of exclusion or marginalization” | social marginalization, prevent marginalization |

| cognitive function | n | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˈfʌŋkʃn/ | chức năng nhận thức | “neurochemicals…enhance cognitive function” | improve cognitive function, cognitive function development |

| posit | v | /ˈpɒzɪt/ | cho rằng, đề xuất | “This theory posits that individuals…” | posit a theory, researchers posit |

| validate | v | /ˈvælɪdeɪt/ | công nhận, xác nhận | “When schools validate and celebrate diverse identities” | validate identities, validate experiences |

| stereotype threat | n | /ˈsteriətaɪp θret/ | đe dọa bởi định kiến | “The concept of stereotype threat” | experience stereotype threat, combat stereotype threat |

| inadvertently | adv | /ˌɪnədˈvɜːtəntli/ | vô tình, không cố ý | “they may inadvertently fulfill these stereotypes” | inadvertently reinforce, inadvertently create |

| counteract | v | /ˌkaʊntərˈækt/ | chống lại, phản tác dụng | “actively work to counteract stereotype threat” | counteract effects, counteract stereotypes |

| pioneer | v | /ˌpaɪəˈnɪə/ | tiên phong, khởi xướng | “Growth mindset theory, pioneered by…” | pioneer research, pioneer approach |

| internalize | v | /ɪnˈtɜːnəlaɪz/ | tiếp thu vào trong, nội hóa | “they internalize the message that…” | internalize beliefs, internalize values |

| intergroup | adj | /ˈɪntəɡruːp/ | giữa các nhóm | “prejudice and intergroup tensions” | intergroup relations, intergroup contact |

| relatedness | n | /rɪˈleɪtɪdnəs/ | sự liên kết, quan hệ | “autonomy, competence, and relatedness” | sense of relatedness, psychological relatedness |

| intrinsic motivation | n | /ɪnˈtrɪnsɪk ˌməʊtɪˈveɪʃn/ | động lực nội tại | “students experience intrinsic motivation” | develop intrinsic motivation, foster intrinsic motivation |

| empathy networks | n | /ˈempəθi ˈnetwɜːks/ | mạng lưới thần kinh đồng cảm | “the brain’s empathy networks” | activate empathy networks, empathy networks development |

| psychological flexibility | n | /ˌsaɪkəˈlɒdʒɪkl ˌfleksəˈbɪləti/ | sự linh hoạt tâm lý | “contributes to psychological flexibility” | develop psychological flexibility, enhance psychological flexibility |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| systemic transformation | n | /sɪˈstemɪk ˌtrænsfəˈmeɪʃn/ | chuyển đổi hệ thống | “implementing inclusive education at scale” | achieve systemic transformation, systemic transformation process |

| segregated | adj | /ˈseɡrɪɡeɪtɪd/ | phân biệt, tách biệt | “from segregated or mainstream educational models” | segregated education, segregated systems |

| organizational inertia | n | /ˌɔːɡənaɪˈzeɪʃənl ɪˈnɜːʃə/ | sự trì trệ tổ chức | “mechanisms of organizational inertia” | overcome organizational inertia, organizational inertia resistance |

| path dependence | n | /pɑːθ dɪˈpendəns/ | sự phụ thuộc vào quỹ đạo | “organizational inertia and path dependence” | institutional path dependence, path dependence effects |

| homogeneity | n | /ˌhɒmədʒəˈniːəti/ | tính đồng nhất | “assumptions of student homogeneity” | cultural homogeneity, student homogeneity |

| dismantling | v/n | /dɪsˈmæntlɪŋ/ | phá bỏ, tháo dỡ | “Dismantling these structures requires…” | dismantling barriers, dismantling stereotypes |

| longitudinal | adj | /ˌlɒndʒɪˈtjuːdɪnl/ | dọc theo thời gian, lâu dài | “longitudinal economic analyses” | longitudinal study, longitudinal research |

| duplication | n | /ˌdjuːplɪˈkeɪʃn/ | sự trùng lặp | “reducing duplication of services” | avoid duplication, minimize duplication |

| leverage points | n | /ˈliːvərɪdʒ pɔɪnts/ | điểm tác động then chốt | “represent critical leverage points” | identify leverage points, strategic leverage points |

| decontextualized | adj | /ˌdiːkənˈtekstʃuəlaɪzd/ | tách rời bối cảnh | “limited, decontextualized coursework” | decontextualized learning, decontextualized knowledge |

| adaptive expertise | n | /əˈdæptɪv ˌekspɜːˈtiːz/ | chuyên môn thích ứng | “toward adaptive expertise” | develop adaptive expertise, build adaptive expertise |

| perverse incentives | n | /pəˈvɜːs ɪnˈsentɪvz/ | động cơ trái ngược mục đích | “create perverse incentives” | perverse incentives problem, avoid perverse incentives |

| accountability frameworks | n | /əˌkaʊntəˈbɪləti ˈfreɪmwɜːks/ | khung trách nhiệm giải trình | “multidimensional accountability frameworks” | develop accountability frameworks, effective accountability frameworks |

| entrenched | adj | /ɪnˈtrentʃt/ | ăn sâu, bám rễ | “deeply entrenched beliefs” | entrenched attitudes, entrenched practices |

| iterative process | n | /ˈɪtərətɪv ˈprəʊses/ | quá trình lặp đi lặp lại | “The iterative process of community dialogue” | iterative process design, continuous iterative process |

| digital divide | n | /ˈdɪdʒɪtl dɪˈvaɪd/ | khoảng cách số | “The digital divide encompasses…” | bridge digital divide, address digital divide |

| algorithmic sorting | n | /ˌælɡəˈrɪðmɪk ˈsɔːtɪŋ/ | phân loại bằng thuật toán | “algorithmic sorting and adaptive learning systems” | algorithmic sorting systems, prevent algorithmic sorting |

| temporal dimensions | n | /ˈtempərəl daɪˈmenʃnz/ | các khía cạnh thời gian | “The temporal dimensions of transformation” | consider temporal dimensions, temporal dimensions analysis |

Công nghệ hỗ trợ học tập trong môi trường giáo dục hòa nhập hiện đại

Công nghệ hỗ trợ học tập trong môi trường giáo dục hòa nhập hiện đại

Kết bài

Chủ đề “How To Foster Inclusivity In Schools” không chỉ là một nội dung quan trọng trong đời sống giáo dục hiện đại mà còn là một chủ đề phổ biến và đầy thách thức trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Qua ba passages với độ khó tăng dần, bạn đã được trải nghiệm cách IELTS kiểm tra khả năng đọc hiểu từ nhiều góc độ khác nhau – từ thông tin cơ bản về môi trường học đường hòa nhập, đến các nền tảng tâm lý học sâu sắc, và cuối cùng là những thách thức phức tạp trong việc thực hiện chuyển đổi hệ thống giáo dục.

Ba passages đã cung cấp đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng câu hỏi khác nhau, giúp bạn làm quen với hầu hết các dạng câu hỏi có thể xuất hiện trong kỳ thi thật. Passage 1 tập trung vào việc xây dựng kỹ năng đọc lướt và xác định thông tin cụ thể. Passage 2 đòi hỏi khả năng hiểu các mối quan hệ nhân quả và so sánh các quan điểm lý thuyết. Passage 3 thử thách bạn với văn phong học thuật cao cấp và yêu cầu khả năng phân tích, tổng hợp thông tin từ nhiều nguồn.

Phần đáp án chi tiết không chỉ cung cấp đáp án đúng mà còn giải thích rõ ràng lý do tại sao đó là đáp án chính xác, vị trí cụ thể trong bài, và cách paraphrase được sử dụng giữa câu hỏi và passage. Đây chính là chìa khóa để bạn phát triển kỹ năng làm bài IELTS Reading hiệu quả – không chỉ tìm được đáp án mà còn hiểu được logic đằng sau mỗi câu hỏi.

Bộ từ vựng được tổng hợp từ ba passages bao gồm hơn 40 từ và cụm từ quan trọng, từ cơ bản đến nâng cao, đều là những từ thường xuất hiện trong các bài thi IELTS Reading về chủ đề giáo dục và xã hội. Việc học và sử dụng thành thạo những từ vựng này sẽ giúp bạn không chỉ trong phần Reading mà còn trong Writing và Speaking.

Để đạt kết quả tốt nhất, hãy làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật với giới hạn thời gian, sau đó đối chiếu đáp án, đọc kỹ phần giải thích, và rút ra bài học cho bản thân. Luyện tập thường xuyên với các đề thi mẫu chất lượng như thế này sẽ giúp bạn tự tin hơn và đạt band điểm mục tiêu trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!