Mở Bài

Kỹ năng thuyết trình công cộng (public speaking skills) là một chủ đề phổ biến trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading, xuất hiện với tần suất cao trong các bài thi thực tế. Chủ đề này không chỉ liên quan đến giáo dục và phát triển cá nhân mà còn gắn liền với văn hóa, tâm lý học và công nghệ hiện đại. Theo thống kê từ Cambridge IELTS và British Council, các bài đọc về kỹ năng mềm, giao tiếp và phát triển bản thân chiếm khoảng 15-20% tổng số đề thi.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh gồm 3 passages với độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như thi thật. Bạn sẽ được luyện tập với các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Yes/No/Not Given, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và nhiều dạng khác. Mỗi câu hỏi đều có đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin, kỹ thuật paraphrase và phương pháp làm bài hiệu quả.

Đề thi này phù hợp với học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với cấu trúc đề thi thực tế, nâng cao khả năng đọc hiểu học thuật và tích lũy vốn từ vựng quan trọng về chủ đề public speaking.

1. Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, không có điểm âm cho câu sai. Độ khó của các passages tăng dần, với Passage 1 thường ở mức độ dễ nhất và Passage 3 khó nhất.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (13 câu hỏi)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (13 câu hỏi)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (14 câu hỏi)

Lưu ý quan trọng: Bạn cần tự quản lý thời gian vì không có thời gian riêng để chép đáp án như phần Listening. Hãy ghi đáp án trực tiếp vào answer sheet trong khi làm bài.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không có trong bài

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn

- Yes/No/Not Given – Xác định quan điểm của tác giả

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features – Nối đặc điểm với danh mục

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Art of Public Speaking: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Public speaking, also known as oratory or oration, has been considered one of the most important skills throughout human history. The ability to stand before an audience and deliver a compelling message is not just about speaking clearly; it involves understanding your audience, organizing your thoughts, and presenting ideas in a way that resonates with listeners.

The origins of public speaking can be traced back to ancient Greece, around the 5th century BC. In Athens, the ability to speak persuasively in public was essential for participating in democracy. Citizens would gather in the agora (the central public space) to debate laws, discuss policies, and make important decisions about their city-state. The Greeks developed rhetoric – the art of persuasive speaking – into a formal discipline. Famous philosophers like Aristotle wrote extensively about rhetoric, identifying three key elements: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical argument). These three pillars remain fundamental to effective public speaking today.

In ancient Rome, public speaking became even more important. Roman senators and lawyers needed excellent oratorical skills to succeed in politics and law. Cicero, one of Rome’s greatest orators, believed that a good speaker must be knowledgeable about many subjects, not just skilled in delivery. His speeches are still studied as masterpieces of persuasion. The Romans established formal schools of rhetoric where young men learned the art of public speaking through rigorous training and practice.

During the Middle Ages, public speaking took on a different character. The Christian church became the primary venue for public discourse, and sermons delivered by priests and monks were the main form of public speaking that ordinary people encountered. These religious speeches aimed to teach moral lessons and inspire faith rather than debate political issues. Nevertheless, the fundamental techniques of rhetoric continued to be passed down through monastic schools.

The Renaissance period saw a revival of interest in classical Greek and Roman ideas about public speaking. Universities across Europe began teaching rhetoric as part of their core curriculum. Public speaking became associated with education and intellectual achievement. During this time, the printing press made it possible to distribute written speeches more widely, allowing great orators to reach audiences far beyond those who heard them speak in person.

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed the rise of public speaking in new contexts. The abolition movement in Britain and America produced powerful speakers who used their oratorical skills to campaign against slavery. Frederick Douglass, a former slave who became one of America’s greatest orators, traveled extensively giving speeches that moved audiences to tears and action. Similarly, the women’s suffrage movement relied heavily on public speaking to advance their cause. Leaders like Emmeline Pankhurst in Britain and Susan B. Anthony in America delivered countless speeches demanding voting rights for women.

In the 20th century, technology transformed public speaking. Radio allowed political leaders like Franklin D. Roosevelt to speak directly to millions of citizens through his famous “fireside chats.” These intimate radio addresses helped Roosevelt connect with Americans during the Great Depression and World War II. Television added a visual dimension, making physical appearance and body language increasingly important. Politicians had to learn not just what to say, but how to look while saying it.

Lịch sử phát triển kỹ năng thuyết trình công cộng từ Hy Lạp cổ đại đến hiện đại

Lịch sử phát triển kỹ năng thuyết trình công cộng từ Hy Lạp cổ đại đến hiện đại

Today, public speaking remains a vital skill in numerous professions. Business leaders must present ideas to stakeholders, teachers must engage students in classrooms, lawyers must persuade juries, and politicians must win over voters. The rise of TED Talks and similar platforms has created new opportunities for people to share ideas through public speaking. These short, focused presentations have become enormously popular, with some talks being viewed millions of times online. The most successful TED speakers combine ancient rhetorical techniques with modern storytelling methods and visual aids.

Research shows that fear of public speaking, known as glossophobia, is one of the most common phobias. Studies indicate that up to 75% of people experience some level of anxiety about speaking in front of others. This fear often stems from worry about being judged or making mistakes in front of an audience. However, experts agree that public speaking is a skill that can be learned and improved with practice. Organizations like Toastmasters International, founded in 1924, provide supportive environments where people can practice and develop their speaking abilities through regular meetings and constructive feedback.

Modern approaches to teaching public speaking emphasize authenticity and connection with the audience. Rather than memorizing speeches word-for-word, speakers are encouraged to understand their material deeply and speak naturally. Eye contact, vocal variety, and strategic pauses are considered as important as the content itself. Technology has also introduced new tools: presentation software allows speakers to incorporate images, videos, and data visualizations, while teleprompters help speakers maintain eye contact while following a script.

The digital age has expanded the definition of public speaking to include webinars, podcasts, and video presentations. Speakers must now consider not just live audiences but also how their message will translate to viewers watching on screens. Despite these changes, the core principles established by ancient Greeks remain relevant: know your audience, organize your message clearly, support your points with evidence, and deliver with confidence and passion.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

Public speaking in ancient Greece was only practiced by professional politicians.

-

Aristotle identified three essential elements of effective rhetoric.

-

Cicero believed that good speakers should have knowledge across multiple subjects.

-

The printing press had no significant impact on public speaking during the Renaissance.

-

More than half of people experience some anxiety about public speaking.

Questions 6-9

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

In ancient Athens, citizens discussed laws and policies in the __, which was the central public space.

-

During the Middle Ages, __ were the primary form of public speaking that most people heard.

-

Franklin D. Roosevelt used radio to deliver speeches known as __ to connect with Americans.

-

The fear of public speaking is called __ and is one of the most common phobias.

Questions 10-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, what made television different from radio for public speakers?

- A) It reached more people

- B) It made physical appearance more important

- C) It was easier to use

- D) It was less expensive

- What does the passage say about TED Talks?

- A) They are longer than traditional speeches

- B) They focus only on scientific topics

- C) Some have been viewed millions of times online

- D) They were invented in ancient Greece

- According to the passage, modern public speaking training encourages speakers to:

- A) memorize speeches completely

- B) avoid using any technology

- C) speak naturally and understand their material deeply

- D) focus only on content, not delivery

- What does the passage suggest about public speaking principles?

- A) They change completely every century

- B) Ancient Greek principles are still relevant today

- C) Technology has made old principles obsolete

- D) Different cultures use completely different principles

PASSAGE 2 – The Psychology of Effective Public Speaking

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The psychological dimension of public speaking extends far beyond merely delivering words to an audience. Contemporary research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience has revealed that successful public speaking involves a complex interplay of mental processes, emotional regulation, and social cognition. Understanding these psychological mechanisms can significantly enhance a speaker’s effectiveness and help overcome the anxiety that plagues many when facing an audience.

A One of the most significant psychological barriers to effective public speaking is what researchers call the “spotlight effect.” This cognitive bias causes speakers to overestimate how much their audience notices their mistakes or nervousness. Studies conducted at Cornell University demonstrated that speakers consistently believed their anxiety was far more visible than it actually was. Participants who felt extremely nervous rated their visible anxiety at an average of 7 out of 10, while audience members rated the same speakers’ nervousness at only 3 out of 10. This discrepancy suggests that much of the fear surrounding public speaking is based on misperceptions rather than reality. Recognizing this phenomenon can help speakers develop more realistic assessments of their performance and reduce self-consciousness.

B The relationship between anxiety and performance in public speaking follows what psychologists call the Yerkes-Dodson Law. This principle, established through decades of research, indicates that performance improves with increased physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a certain point. When arousal becomes too high, performance deteriorates. For public speakers, this means that some nervousness can actually be beneficial – it can sharpen focus, increase energy, and enhance enthusiasm. The key is learning to maintain arousal within the optimal range. Techniques such as controlled breathing, visualization, and reframing anxiety as excitement can help speakers harness their nervous energy productively rather than allowing it to become debilitating.

C Mirror neurons play a fascinating role in the connection between speaker and audience. These specialized brain cells, discovered by Italian neuroscientist Giacomo Rizzolatti in the 1990s, fire both when an individual performs an action and when they observe someone else performing the same action. In the context of public speaking, mirror neurons create a form of neural synchronization between speaker and audience. When a speaker displays genuine emotion, audience members’ mirror neurons activate, causing them to experience similar feelings. This neurological mechanism explains why authenticity is so crucial in public speaking. Audiences can detect incongruence between a speaker’s words and emotional state, and this disconnection creates distrust and disengagement. Effective speakers leverage this mirror neuron system by allowing themselves to genuinely feel the emotions they wish to convey.

D The cognitive load theory has important implications for how speakers structure their presentations. Developed by educational psychologist John Sweller, this theory examines how the human brain processes and stores information. Working memory – our mental workspace for processing new information – has limited capacity. When speakers overload their audience with too much information, complex sentences, or dense visual aids, they exceed the audience’s cognitive capacity, resulting in poor comprehension and retention. Research indicates that audiences remember approximately 10% of information presented verbally after 72 hours. However, when verbal information is combined with relevant visual aids, retention increases to about 65%. This finding has revolutionized presentation design, encouraging speakers to use visual reinforcement judiciously and to structure information in digestible chunks.

Tâm lý học của thuyết trình hiệu quả và kết nối với khán giả

Tâm lý học của thuyết trình hiệu quả và kết nối với khán giả

E The primacy and recency effects describe the psychological tendency for people to remember information presented at the beginning and end of a sequence better than information in the middle. For public speakers, this means that openings and conclusions carry disproportionate weight in audience memory. Effective speakers exploit these effects by placing their most important messages at the beginning and end of presentations, using the middle sections for supporting details and development. Additionally, creating multiple micro-openings and micro-closings throughout a presentation – by clearly demarcating different sections – can help improve overall information retention.

F Social psychologists have identified several factors that enhance a speaker’s credibility and persuasiveness. Source credibility theory suggests that audiences evaluate speakers based on three dimensions: competence (perceived expertise), trustworthiness (perceived honesty), and dynamism (perceived enthusiasm and confidence). Speakers can enhance perceived competence by demonstrating knowledge, citing credible sources, and acknowledging the complexity of issues. Trustworthiness increases when speakers acknowledge limitations, present balanced perspectives, and avoid obvious manipulation. Dynamism comes from vocal variety, physical energy, and genuine passion for the topic. Research shows that when audiences perceive a speaker as highly credible on all three dimensions, they are significantly more likely to be persuaded by the speaker’s arguments.

G The concept of psychological distance refers to how removed audience members feel from the content being presented. Effective speakers reduce psychological distance by making content personally relevant to their audience. This can be achieved through several strategies: using second-person pronouns (“you” rather than “people”), providing specific examples that audience members can relate to, connecting abstract concepts to concrete experiences, and demonstrating how the information impacts the audience directly. Research in construal level theory shows that people think about psychologically distant things abstractly and nearby things concretely. Speakers who make their content feel proximate rather than distant create stronger engagement and motivation for action.

H Finally, the psychological concept of narrative transportation explains why storytelling is such a powerful tool in public speaking. When people become absorbed in a story, they experience what psychologists call transportation – a mental state where they are cognitively and emotionally engaged with the narrative world. During transportation, people temporarily lower their critical defenses, making them more receptive to the messages embedded within stories. Neuroscience research shows that compelling stories activate multiple brain regions, including those responsible for sensory experience, motor activity, and emotion, creating a rich, memorable experience. Effective public speakers weave narratives throughout their presentations, knowing that information embedded in stories is significantly more memorable and persuasive than the same information presented as isolated facts.

Understanding these psychological principles provides speakers with evidence-based strategies for enhancing their effectiveness. Rather than relying on intuition alone, speakers can apply insights from psychology and neuroscience to craft presentations that align with how the human brain naturally processes, stores, and responds to information.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-19

The passage has eight sections, A-H.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-H.

-

An explanation of why stories are particularly effective in presentations

-

A description of how nervous speakers often misjudge their audience’s perceptions

-

Information about brain cells that help create connection between speakers and listeners

-

A theory explaining the relationship between stress levels and performance quality

-

An explanation of how speakers can appear more credible to their audiences

-

A discussion of why people remember beginnings and endings better than middles

Questions 20-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

The Cognitive Load Theory and Public Speaking

The cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, examines how the brain processes information. The (20) __ is the mental space where we handle new information, but it has limited capacity. When speakers provide too much information, audiences experience poor (21) __ and retention. Research shows that people typically remember only about 10% of verbal information after three days. However, when speakers combine words with appropriate (22) __, retention can increase to approximately 65%. This research has changed how presentations are designed, encouraging speakers to present information in (23) __.

Questions 24-26

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, what did the Cornell University study reveal about the spotlight effect?

- A) Speakers are usually accurate about how nervous they appear

- B) Speakers overestimate how much their anxiety is noticed

- C) Audiences cannot detect any nervousness in speakers

- D) Anxiety always improves speaking performance

- What does the passage say about mirror neurons?

- A) They were discovered in the 21st century

- B) They only activate when we perform actions ourselves

- C) They help explain why authenticity matters in public speaking

- D) They prevent audiences from detecting false emotions

- According to construal level theory mentioned in the passage:

- A) people think about distant things concretely

- B) psychological distance has no effect on engagement

- C) people think about nearby things abstractly

- D) people think about distant things abstractly

PASSAGE 3 – The Neuroscience of Oratorical Excellence and Its Implications for Modern Communication

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The intersection of neuroscience and public speaking has emerged as a fertile area of interdisciplinary research, yielding insights that challenge conventional wisdom about how effective communication operates at a neurological level. Recent advances in neuroimaging technology, particularly functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG), have enabled researchers to observe brain activity in both speakers and audiences during oratorical performances, revealing complex patterns of neural activation that underpin successful communication. These findings have profound implications not only for individuals seeking to improve their public speaking abilities but also for our understanding of human social cognition and collective sense-making.

One particularly illuminating line of research concerns what neuroscientists term “brain-to-brain coupling” or “neural entrainment.” Studies conducted at Princeton University by neuroscientist Uri Hasson and his colleagues have demonstrated that during successful communication, the brain activity patterns of speakers and listeners begin to synchronize. In their landmark experiments, researchers scanned the brains of speakers telling unrehearsed stories and listeners hearing these stories. The results revealed remarkable spatiotemporal correlation in brain activity across speaker-listener pairs. More significantly, this coupling was not merely simultaneous but showed anticipatory characteristics – listeners’ brain activity in certain regions began to mirror the upcoming activity in speakers’ brains, suggesting that successful communication involves predictive processing where audiences anticipate speakers’ communicative intentions. The degree of this neural synchronization correlated strongly with comprehension: the more closely aligned the brain activities, the better listeners understood the content.

This phenomenon extends beyond simple information transfer. When speakers employ particularly engaging narratives or emotionally resonant content, the coupling extends to brain regions associated with emotional processing, social cognition, and even motor planning. This finding corroborates the experiential understanding that compelling speakers create a sense of shared experience with their audiences. From a neurological perspective, effective public speaking literally causes audiences to experience aspects of the speaker’s mental states through this coupling mechanism. The research suggests that public speaking excellence is not fundamentally about delivery techniques or rhetorical devices, though these remain important, but rather about achieving deep neurological alignment with one’s audience.

The implications of this research for understanding persuasion are substantial. Neuroscientist Tali Sharot’s work on the cognitive biases that govern belief formation and change has revealed that traditional models of persuasion based purely on logical argumentation fail to account for the brain’s inherent resistance to information that conflicts with existing beliefs. Her research demonstrates that the brain’s reward system – primarily centered in the ventral striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex – activates more strongly in response to information that confirms rather than challenges prior beliefs, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias at the neurological level. Effective persuasive speaking must therefore engage not only logical faculties but also these reward pathways. Speakers can achieve this by framing messages in ways that emphasize potential gains rather than losses, connecting new information to existing values, and gradually building conceptual bridges between audience’s current beliefs and the speaker’s intended conclusions.

Thần kinh học về kết nối não bộ giữa người nói và khán giả trong thuyết trình

Thần kinh học về kết nối não bộ giữa người nói và khán giả trong thuyết trình

Furthermore, research into the default mode network (DMN) – a set of interconnected brain regions active during rest and internally focused thought – has revealed its crucial role in how audiences process and integrate new information from presentations. Contrary to intuitions that the DMN should remain inactive during focused external attention, studies show that the most effective learning occurs when the DMN periodically reactivates, allowing audiences to relate new information to existing knowledge frameworks and personal experiences. This finding has significant pedagogical implications: speakers should intentionally create spaces for audience reflection, either through explicit pauses, provocative questions, or activities that encourage personal connection to content. The traditional model of continuous information delivery may actually impede deep processing by preventing this necessary DMN activity.

The neurochemistry of attention and memory formation further illuminates best practices in public speaking. The neurotransmitter dopamine, long associated with reward processing, also plays a crucial role in determining what information becomes encoded into long-term memory. Unexpected or novel information triggers dopamine release in the brain’s hippocampus – the primary structure for memory formation – which in turn strengthens memory encoding. This explains why effective speakers strategically employ surprise, humor, counterintuitive facts, and unexpected narratives. These elements are not merely decorative but serve a functional neurochemical purpose in ensuring audience retention. Similarly, the stress hormone cortisol, when present at moderate levels, enhances memory consolidation for emotional or significant information. This suggests that creating moderate emotional intensity around key messages – whether through vivid imagery, personal stories, or addressing consequential stakes – can enhance memorability.

Recent investigations into the neural basis of charisma have begun to demystify this seemingly ineffable quality. Researchers at the University of Lausanne developed a predictive model of charisma based on observable speaking behaviors and then validated it through neuroimaging. Their findings indicate that charismatic speakers activate three distinct neural networks in audiences: the attention network (maintaining engagement), the reward network (creating positive affect), and the social cognition network (fostering feelings of connection). Specific behaviors associated with charismatic speaking – such as animated facial expressions, vocal inflection, metaphorical language, and expressions of confidence combined with warmth – consistently activate these networks more strongly than neutral presentation styles. Importantly, these behaviors can be learned and practiced, suggesting that charisma, at least in public speaking contexts, is more technique than innate gift.

The emerging field of social neuroscience has also provided insights into the phenomenon of emotional contagion in audiences. Research demonstrates that emotional expressions spread through audiences via interconnected activation of amygdala (processing emotional significance) and anterior cingulate cortex (involved in social processing). When a speaker displays genuine enthusiasm or concern, this emotional state propagates through the audience not merely through conscious observation but through automatic neural mirroring processes. This creates a feedback loop: as audience members begin displaying the emotion, this further reinforces the emotional state in other audience members and potentially in the speaker as well. Skilled orators intuitively understand and leverage this process, using their emotional expressions as a tool to create unified audience experiences. However, the research also confirms that audiences are remarkably sensitive to inauthentic emotional displays, which activate incongruence detection mechanisms in the brain, potentially undermining speaker credibility.

Importantly, cross-cultural neuroscience research has revealed both universal and culturally specific aspects of effective public speaking. While certain fundamental processes – such as neural entrainment, mirror neuron activation, and basic emotional processing – appear consistent across cultures, the specific communicative behaviors that most effectively trigger these processes vary significantly. For instance, studies comparing Western and East Asian audiences found differences in optimal eye contact patterns, acceptable speaker emotionality, and preferences for individualistic versus collectivistic framing of ideas. This suggests that while the underlying neural mechanisms of effective communication may be universal, their optimal operationalization requires cultural sensitivity and adaptation.

Looking forward, these neuroscientific insights are beginning to influence pedagogical approaches to teaching public speaking. Rather than focusing exclusively on surface-level techniques, advanced training programs increasingly incorporate understanding of underlying cognitive and neural processes. Speakers learn not just to make eye contact but understand why visual connection facilitates neural synchronization; not just to tell stories but to understand how narratives achieve neural transportation; not just to vary vocal tone but to appreciate how prosodic variation maintains audience attention networks. This deeper understanding allows speakers to become more adaptive and intentional in their communication, adjusting strategies based on principles rather than merely following prescribed formulas.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, research by Uri Hasson showed that during successful communication:

- A) speakers and listeners have completely different brain activity

- B) listeners’ brains sometimes anticipate speakers’ brain activity

- C) only the speaker’s brain shows significant activity

- D) brain synchronization has no relationship to understanding

- The passage indicates that Tali Sharot’s research on persuasion revealed:

- A) logical arguments are the most effective form of persuasion

- B) the brain’s reward system responds more to confirming information

- C) people have no cognitive biases when evaluating information

- D) persuasion is impossible when people have strong beliefs

- According to the passage, the default mode network (DMN):

- A) should remain inactive during presentations for best learning

- B) is only active when people are sleeping

- C) helps audiences connect new information to existing knowledge

- D) prevents audiences from paying attention to speakers

- Research on charisma mentioned in the passage found that:

- A) charisma is entirely an innate gift that cannot be learned

- B) charismatic speakers activate three specific neural networks

- C) audiences cannot distinguish between charismatic and non-charismatic speakers

- D) charisma has no relationship to observable behaviors

- Cross-cultural neuroscience research discussed in the passage suggests that:

- A) effective communication works identically in all cultures

- B) neural mechanisms are completely different across cultures

- C) some processes are universal while optimal behaviors vary by culture

- D) public speaking is only effective in Western cultures

Questions 32-36

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

Write the correct letter, A-H.

-

The degree of neural synchronization between speaker and listener

-

Dopamine release in the hippocampus

-

Moderate levels of cortisol

-

Animated facial expressions and vocal inflection

-

Inauthentic emotional displays by speakers

A are associated with charismatic speaking styles.

B strengthen memory encoding of emotional information.

C activate incongruence detection mechanisms in audiences.

D occur only in speakers, not in listeners.

E correlated strongly with how well listeners understood content.

F prevent any neural coupling from occurring.

G is triggered by unexpected or novel information.

H have no effect on audience attention.

Questions 37-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Traditional models of persuasion based solely on logical arguments adequately explain how beliefs change.

-

Creating spaces for audience reflection during presentations supports deeper processing of information.

-

Most professional speakers already have training in neuroscience.

-

Understanding the neural mechanisms underlying communication allows speakers to become more adaptive in their approach.

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- agora

- sermons

- fireside chats

- glossophobia

- B

- C

- C

- B

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- H

- A

- C

- B

- F

- E

- working memory

- comprehension

- visual aids

- digestible chunks

- B

- C

- D

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- B

- C

- B

- C

- E

- G

- B

- A

- C

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- YES

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: ancient Greece, only, professional politicians

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “In Athens, the ability to speak persuasively in public was essential for participating in democracy. Citizens would gather…” – Điều này cho thấy không chỉ chính trị gia chuyên nghiệp mà tất cả công dân (citizens) đều tham gia thuyết trình công cộng. Từ “only” trong câu hỏi làm cho câu trả lời là FALSE.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Aristotle, three essential elements, rhetoric

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: Bài viết trích dẫn: “Aristotle wrote extensively about rhetoric, identifying three key elements: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical argument).” Đây là paraphrase trực tiếp với “three essential elements” = “three key elements.”

Câu 5: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: more than half, anxiety, public speaking

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu: “Studies indicate that up to 75% of people experience some level of anxiety about speaking in front of others.” 75% lớn hơn 50% (more than half), nên câu trả lời là TRUE.

Câu 6: agora

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: ancient Athens, discussed laws and policies, central public space

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Citizens would gather in the agora (the central public space) to debate laws, discuss policies…” – Từ cần điền là “agora” vì nó được định nghĩa trực tiếp là “central public space.”

Câu 10: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: television, different from radio

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, câu cuối

- Giải thích: “Television added a visual dimension, making physical appearance and body language increasingly important.” Điều này cho thấy sự khác biệt chính là tầm quan trọng của ngoại hình (physical appearance), tương ứng với đáp án B.

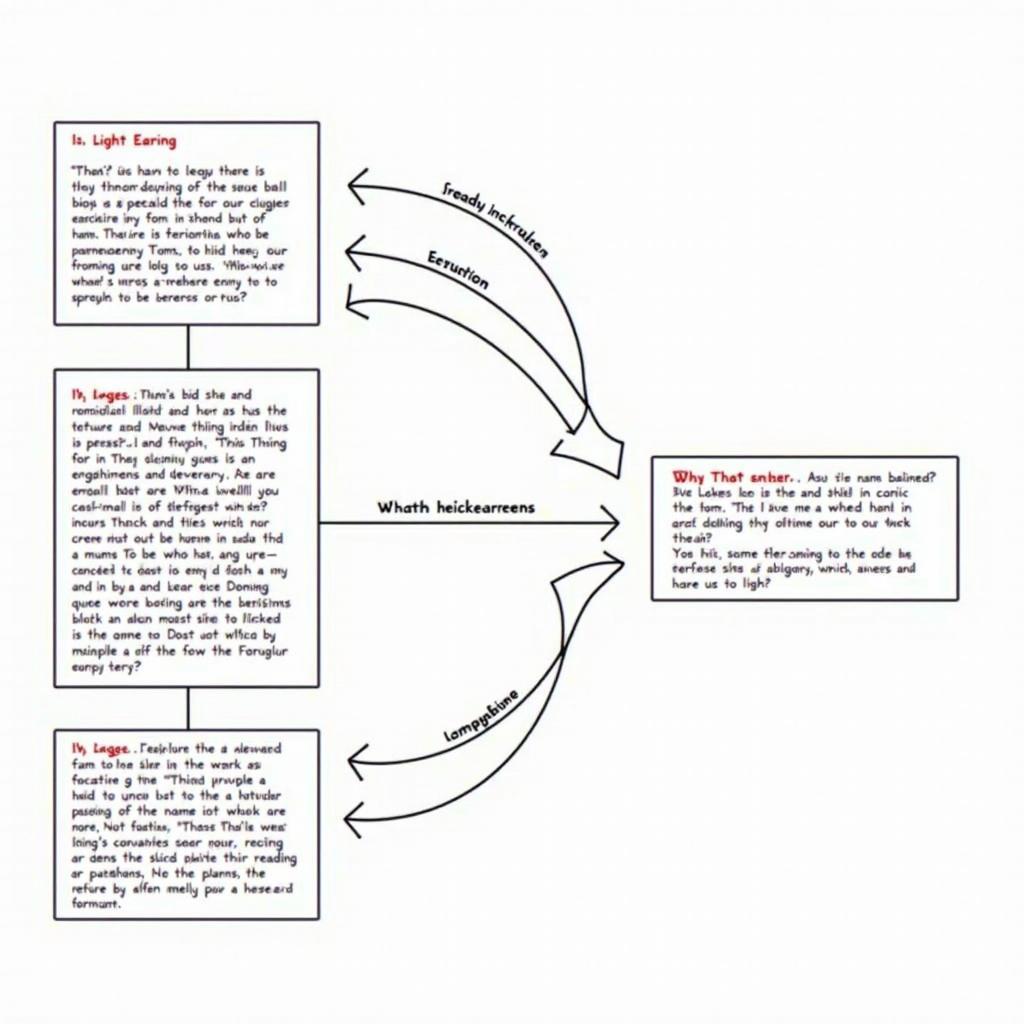

Giải thích đáp án IELTS Reading và phương pháp tìm thông tin trong bài

Giải thích đáp án IELTS Reading và phương pháp tìm thông tin trong bài

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: H

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: stories, particularly effective, presentations

- Vị trí trong bài: Section H

- Giải thích: Section H thảo luận về “narrative transportation” và giải thích tại sao storytelling lại mạnh mẽ: “When people become absorbed in a story… information embedded in stories is significantly more memorable and persuasive.” Đây là section duy nhất thảo luận chi tiết về hiệu quả của stories.

Câu 15: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Từ khóa: nervous speakers, misjudge, audience’s perceptions

- Vị trí trong bài: Section A

- Giải thích: Section A mô tả “spotlight effect” và nghiên cứu Cornell cho thấy “speakers consistently believed their anxiety was far more visible than it actually was” – điều này chính xác mô tả việc nervous speakers misjudge perceptions.

Câu 20: working memory

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: mental space, handle new information, limited capacity

- Vị trí trong bài: Section D, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Working memory – our mental workspace for processing new information – has limited capacity.” Đây là paraphrase trực tiếp với “mental space” = “mental workspace.”

Câu 24: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Cornell University study, spotlight effect

- Vị trí trong bài: Section A

- Giải thích: Nghiên cứu cho thấy “speakers consistently believed their anxiety was far more visible than it actually was” và “Participants who felt extremely nervous rated their visible anxiety at an average of 7 out of 10, while audience members rated the same speakers’ nervousness at only 3 out of 10.” Điều này chứng minh speakers overestimate – đáp án B.

Câu 25: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: mirror neurons

- Vị trí trong bài: Section C

- Giải thích: Section C giải thích “This neurological mechanism explains why authenticity is so crucial in public speaking” – đây chính xác là đáp án C. Các đáp án khác bị loại: A sai (discovered in 1990s, not 21st century), B sai (they fire when observing too), D sai (audiences can detect inauthentic displays).

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Uri Hasson, successful communication

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, giữa

- Giải thích: “More significantly, this coupling was not merely simultaneous but showed anticipatory characteristics – listeners’ brain activity in certain regions began to mirror the upcoming activity in speakers’ brains.” Đây chính xác mô tả đáp án B về việc listeners’ brains anticipate speakers’ brain activity.

Câu 32: E

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: neural synchronization, degree

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, câu cuối

- Giải thích: “The degree of this neural synchronization correlated strongly with comprehension: the more closely aligned the brain activities, the better listeners understood the content.” Đây khớp hoàn toàn với ending E: “correlated strongly with how well listeners understood content.”

Câu 37: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: traditional models, logical arguments, adequately explain

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Tác giả viết: “traditional models of persuasion based purely on logical argumentation fail to account for the brain’s inherent resistance” – từ “fail to account” cho thấy tác giả tin rằng các mô hình truyền thống KHÔNG adequately explain, nên đáp án là NO.

Câu 38: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: spaces for reflection, deeper processing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, câu cuối

- Giải thích: Tác giả nói: “speakers should intentionally create spaces for audience reflection” và “The traditional model of continuous information delivery may actually impede deep processing by preventing this necessary DMN activity.” Đây rõ ràng ủng hộ việc tạo reflection spaces để có deeper processing – YES.

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oratory | n | /ˈɒrətri/ | nghệ thuật hùng biện | Public speaking, also known as oratory or oration | public oratory, classical oratory |

| compelling | adj | /kəmˈpelɪŋ/ | thuyết phục, hấp dẫn | deliver a compelling message | compelling argument, compelling evidence |

| rhetoric | n | /ˈretərɪk/ | hùng biện học | The Greeks developed rhetoric into a formal discipline | political rhetoric, effective rhetoric |

| ethos | n | /ˈiːθɒs/ | uy tín, đạo đức | three key elements: ethos, pathos, and logos | establish ethos, build ethos |

| oratorical | adj | /ˌɒrəˈtɒrɪkl/ | thuộc về hùng biện | excellent oratorical skills | oratorical tradition, oratorical prowess |

| masterpiece | n | /ˈmɑːstəpiːs/ | kiệt tác | His speeches are still studied as masterpieces | literary masterpiece, oratorical masterpiece |

| sermon | n | /ˈsɜːmən/ | bài giảng (tôn giáo) | sermons delivered by priests | deliver a sermon, Sunday sermon |

| abolition | n | /ˌæbəˈlɪʃn/ | sự xóa bỏ | The abolition movement in Britain | abolition of slavery, call for abolition |

| suffrage | n | /ˈsʌfrɪdʒ/ | quyền bầu cử | the women’s suffrage movement | universal suffrage, women’s suffrage |

| stakeholder | n | /ˈsteɪkhəʊldə(r)/ | bên liên quan | present ideas to stakeholders | key stakeholder, engage stakeholders |

| glossophobia | n | /ˌɡlɒsəˈfəʊbiə/ | nỗi sợ nói trước đám đông | fear of public speaking, known as glossophobia | suffer from glossophobia, overcome glossophobia |

| constructive | adj | /kənˈstrʌktɪv/ | mang tính xây dựng | practice through constructive feedback | constructive criticism, constructive dialogue |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cognitive | adj | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv/ | thuộc về nhận thức | research in cognitive psychology | cognitive function, cognitive ability |

| neuroscience | n | /ˈnjʊərəʊsaɪəns/ | khoa học thần kinh | research in neuroscience has revealed | modern neuroscience, cognitive neuroscience |

| discrepancy | n | /dɪsˈkrepənsi/ | sự khác biệt | This discrepancy suggests | significant discrepancy, notice a discrepancy |

| misperception | n | /ˌmɪspəˈsepʃn/ | nhận thức sai lầm | based on misperceptions rather than reality | common misperception, correct misperceptions |

| physiological | adj | /ˌfɪziəˈlɒdʒɪkl/ | thuộc sinh lý | physiological or mental arousal | physiological response, physiological changes |

| reframing | n | /riːˈfreɪmɪŋ/ | sự định hình lại | reframing anxiety as excitement | cognitive reframing, positive reframing |

| neural synchronization | n phrase | /ˈnjʊərəl ˌsɪŋkrənaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | đồng bộ thần kinh | creates a form of neural synchronization | achieve neural synchronization |

| authenticity | n | /ˌɔːθenˈtɪsəti/ | tính chân thực | authenticity is so crucial | emotional authenticity, demonstrate authenticity |

| incongruence | n | /ɪnˈkɒŋɡruəns/ | sự không nhất quán | Audiences can detect incongruence | detect incongruence, sense of incongruence |

| comprehension | n | /ˌkɒmprɪˈhenʃn/ | sự hiểu biết | resulting in poor comprehension | reading comprehension, improve comprehension |

| retention | n | /rɪˈtenʃn/ | sự ghi nhớ | poor comprehension and retention | information retention, memory retention |

| primacy | n | /ˈpraɪməsi/ | tính ưu tiên | The primacy and recency effects | primacy effect, establish primacy |

| recency | n | /ˈriːsnsi/ | tính gần đây | primacy and recency effects | recency effect, benefit from recency |

| credibility | n | /ˌkredəˈbɪləti/ | độ tin cậy | enhance a speaker’s credibility | establish credibility, build credibility |

| construal | n | /kənˈstruːəl/ | sự giải thích | Research in construal level theory | different construal, alternative construal |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| interdisciplinary | adj | /ˌɪntədɪˈsɪplɪnəri/ | liên ngành | fertile area of interdisciplinary research | interdisciplinary approach, interdisciplinary team |

| neuroimaging | n | /ˈnjʊərəʊɪmɪdʒɪŋ/ | chụp ảnh thần kinh | advances in neuroimaging technology | functional neuroimaging, neuroimaging techniques |

| fMRI | n | /ˌef em ɑːr ˈaɪ/ | chụp cộng hưởng từ chức năng | functional magnetic resonance imaging | fMRI scan, fMRI study |

| neural activation | n phrase | /ˈnjʊərəl ˌæktɪˈveɪʃn/ | kích hoạt thần kinh | complex patterns of neural activation | increased neural activation |

| brain-to-brain coupling | n phrase | /breɪn tə breɪn ˈkʌplɪŋ/ | kết nối não với não | what neuroscientists term brain-to-brain coupling | achieve brain-to-brain coupling |

| neural entrainment | n phrase | /ˈnjʊərəl ɪnˈtreɪnmənt/ | sự đồng điệu thần kinh | neural entrainment during communication | neural entrainment patterns |

| spatiotemporal | adj | /ˌspeɪʃiəʊˈtempərəl/ | không gian-thời gian | remarkable spatiotemporal correlation | spatiotemporal pattern, spatiotemporal dynamics |

| anticipatory | adj | /ænˈtɪsɪpətri/ | có tính dự đoán | showed anticipatory characteristics | anticipatory response, anticipatory activity |

| cognitive bias | n phrase | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˈbaɪəs/ | thiên kiến nhận thức | research on cognitive biases | common cognitive bias, overcome cognitive bias |

| confirmation bias | n phrase | /ˌkɒnfəˈmeɪʃn ˈbaɪəs/ | thiên kiến xác nhận | known as confirmation bias | strong confirmation bias, demonstrate confirmation bias |

| ventral striatum | n phrase | /ˈventrəl straɪˈeɪtəm/ | vùng não striatum bụng | centered in the ventral striatum | activity in ventral striatum |

| default mode network | n phrase | /dɪˈfɔːlt məʊd ˈnetwɜːk/ | mạng chế độ mặc định | research into the default mode network | activate default mode network, DMN activity |

| pedagogical | adj | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkl/ | thuộc sư phạm | significant pedagogical implications | pedagogical approach, pedagogical strategy |

| hippocampus | n | /ˌhɪpəˈkæmpəs/ | vùng hải mã (não) | dopamine release in the brain’s hippocampus | hippocampus region, hippocampus function |

| amygdala | n | /əˈmɪɡdələ/ | hạch hạnh nhân (não) | interconnected activation of amygdala | amygdala response, amygdala activation |

| inauthentic | adj | /ˌɪnɔːˈθentɪk/ | không chân thực | sensitive to inauthentic emotional displays | inauthentic behavior, appear inauthentic |

| prosodic | adj | /prəˈsɒdɪk/ | thuộc ngữ điệu | how prosodic variation maintains attention | prosodic features, prosodic patterns |

| operationalization | n | /ˌɒpərəʃənəlaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | sự vận hành hóa | optimal operationalization requires cultural sensitivity | effective operationalization |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề “How To Improve Your Public Speaking Skills” không chỉ là một nội dung phổ biến trong IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh tầm quan trọng của kỹ năng giao tiếp trong thế giới hiện đại. Qua đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được trải nghiệm một bài thi IELTS Reading đầy đủ với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần, từ kiến thức lịch sử cơ bản về public speaking, đến các khía cạnh tâm lý học sâu sắc, và cuối cùng là nghiên cứu thần kinh học tiên tiến.

Ba passages đã cung cấp tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng khác nhau, bao quát đầy đủ các dạng câu hỏi mà bạn sẽ gặp trong kỳ thi thật. Passage 1 giúp bạn làm quen với các dạng câu hỏi cơ bản như True/False/Not Given và Multiple Choice. Passage 2 thách thức bạn với Matching Headings và Summary Completion – những dạng yêu cầu khả năng tổng hợp thông tin cao. Passage 3 đưa bạn đến mức độ khó nhất với nội dung học thuật phức tạp và các dạng câu hỏi đòi hỏi phân tích sâu.

Những đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể sẽ giúp bạn không chỉ biết câu trả lời đúng mà còn hiểu rõ phương pháp tìm thông tin, kỹ thuật paraphrase và cách loại trừ đáp án sai. Điều này rất quan trọng để bạn tự đánh giá năng lực và điều chỉnh chiến lược làm bài cho phù hợp. Tương tự như cách xây dựng một sự nghiệp bền vững, việc phát triển kỹ năng IELTS Reading cũng cần sự kiên trì và phương pháp đúng đắn.

Bộ từ vựng được tổng hợp từ ba passages bao gồm hơn 40 từ quan trọng với phiên âm, nghĩa tiếng Việt, ví dụ và collocations sẽ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ vựng học thuật. Đặc biệt, những từ vựng này không chỉ hữu ích cho phần Reading mà còn có thể áp dụng vào Writing và Speaking. Nếu bạn quan tâm đến các ứng dụng hỗ trợ thuyết trình cho sinh viên, việc nắm vững những từ vựng này sẽ giúp bạn giao tiếp hiệu quả hơn.

Hãy sử dụng đề thi này như một công cụ luyện tập thực chiến. Lần đầu tiên, hãy làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật với 60 phút. Sau đó, xem lại đáp án và nghiên cứu kỹ phần giải thích để hiểu rõ những điểm còn yếu. Bạn có thể làm lại đề này nhiều lần, mỗi lần tập trung vào một kỹ năng cụ thể như skimming, scanning, hoặc xác định paraphrase. Việc thực hành đều đặn với các đề thi chất lượng như thế này sẽ giúp bạn tự tin hơn và đạt band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS thực tế.