Mở bài

Chủ đề tác động của mạng xã hội đến sức khỏe tâm thần người trưởng thành đang trở thành một trong những đề tài nóng hổi và phổ biến nhất trong các kỳ thi IELTS Reading hiện nay. Với sự bùng nổ của công nghệ và việc sử dụng các nền tảng mạng xã hội ngày càng tăng, Cambridge và IDP đã đưa chủ đề này vào nhiều đề thi chính thức từ năm 2019 đến nay.

Trong bài viết này, bạn sẽ được trải nghiệm một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với cấu trúc chuẩn gồm 3 passages có độ khó tăng dần. Bài thi bao gồm đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi thuộc nhiều dạng khác nhau như True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, Matching Headings, và Summary Completion – giống hệt với đề thi thật. Mỗi passage đi kèm với đáp án chi tiết, giải thích cụ thể vị trí thông tin trong bài, cách paraphrase, cùng danh sách từ vựng quan trọng kèm phiên âm và ví dụ thực tế.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với format đề thi chuẩn quốc tế, rèn luyện kỹ năng skimming, scanning và critical thinking – những kỹ năng cốt lõi để đạt band điểm cao trong phần thi IELTS Reading.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

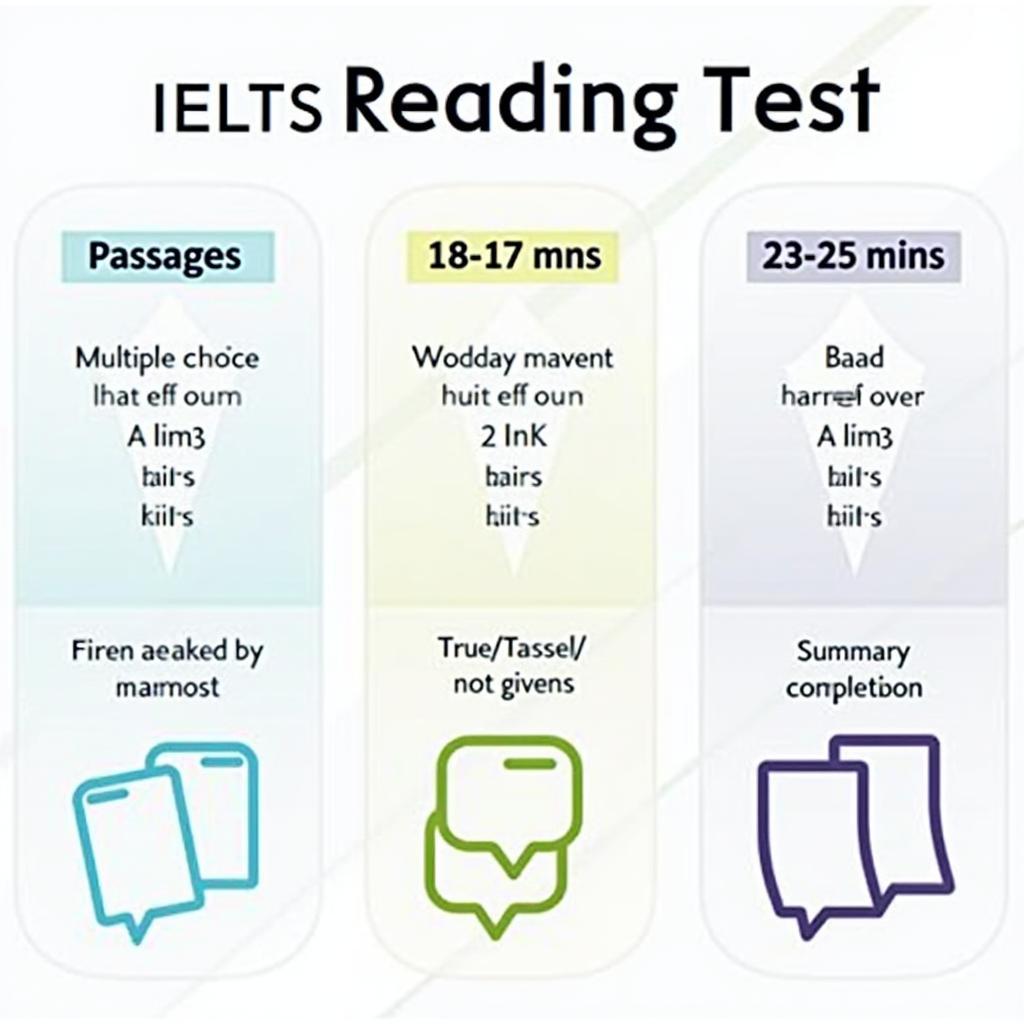

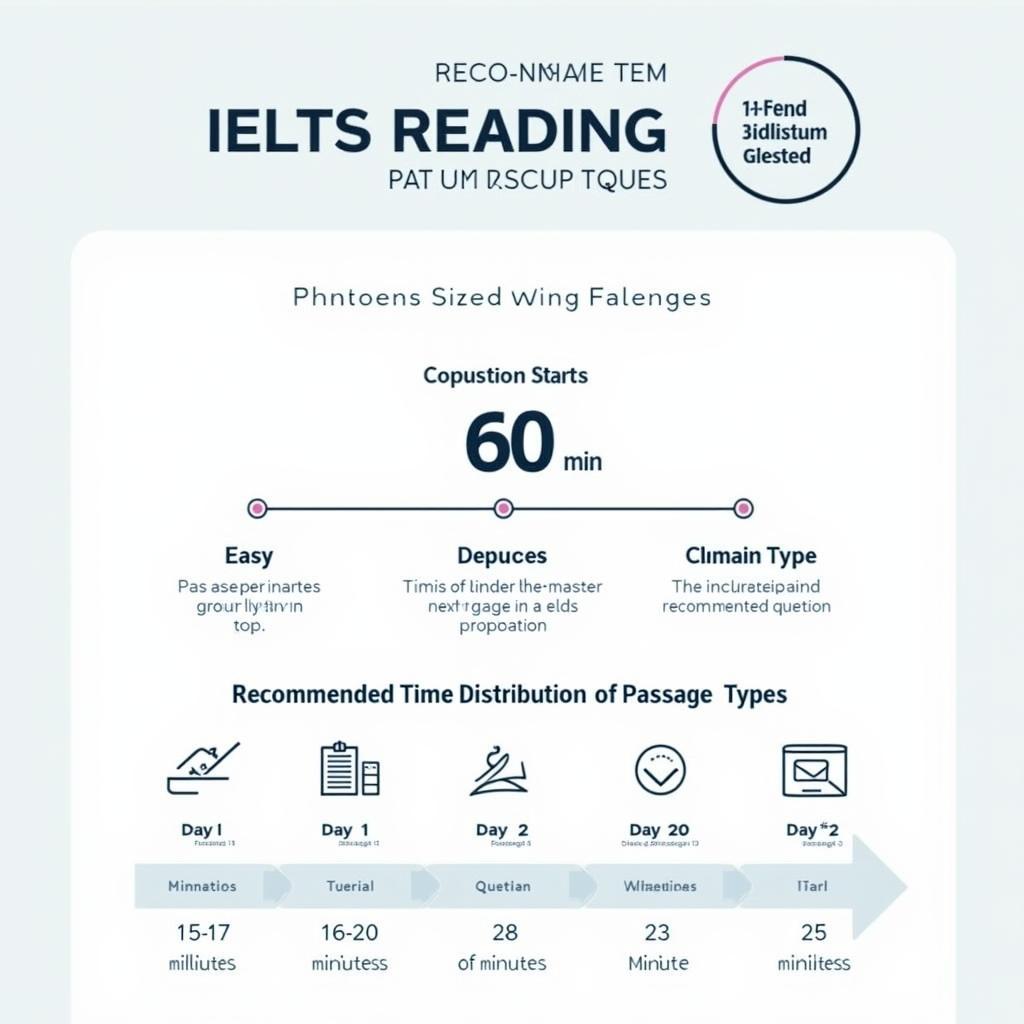

IELTS Reading Test là phần thi kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Đây là bài kiểm tra khả năng đọc hiểu văn bản học thuật của bạn trong điều kiện có giới hạn thời gian. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính là 1 điểm, sau đó quy đổi thành thang điểm band từ 0-9.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1 (Easy): 15-17 phút – Đây là passage dễ nhất, giúp bạn khởi động tốt

- Passage 2 (Medium): 18-20 phút – Độ khó trung bình, yêu cầu tư duy phân tích cao hơn

- Passage 3 (Hard): 23-25 phút – Passage khó nhất với nội dung học thuật và câu hỏi phức tạp

Lưu ý quan trọng: Không có thời gian bổ sung để chép đáp án, vì vậy bạn cần ghi đáp án trực tiếp vào Answer Sheet trong 60 phút.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hay không được đề cập

- Multiple Choice – Chọn đáp án đúng từ các phương án cho sẵn

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề phù hợp với các đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào chỗ trống để hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu với thông tin từ bài đọc

- Matching Features – Nối thông tin với các đặc điểm tương ứng

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn với số từ giới hạn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Social Media Generation: Understanding Digital Connectivity

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The rise of social media platforms over the past two decades has fundamentally transformed how adults communicate, share information, and maintain relationships. What began as simple networking sites has evolved into complex ecosystems that influence nearly every aspect of modern life. From Facebook and Instagram to Twitter and TikTok, these platforms have become integral to daily routines for billions of adults worldwide, with the average user spending approximately 2.5 hours per day scrolling through feeds, posting updates, and engaging with content.

Social media engagement among adults aged 25-54 has reached unprecedented levels, with studies showing that over 80% of this demographic maintains active profiles on at least two platforms. This widespread adoption has created both opportunities and challenges for mental wellbeing. On one hand, these platforms enable people to stay connected with friends and family across vast distances, share life milestones, and find communities with similar interests. Professional networking sites like LinkedIn have revolutionized career development, allowing individuals to showcase their skills and connect with potential employers or collaborators globally.

However, the constant connectivity facilitated by social media has introduced new psychological stressors into adult life. The pressure to present a curated version of oneself online has become a significant source of anxiety for many users. Adults often find themselves comparing their everyday reality to the highlight reels posted by others, leading to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem. Research conducted by the Royal Society for Public Health in the United Kingdom found that Instagram, in particular, was associated with high levels of anxiety, depression, and fear of missing out (FOMO) among adult users.

The dopamine-driven feedback loops created by likes, comments, and shares have been compared to gambling mechanisms, creating addictive patterns of behavior. Neuroscientific studies reveal that receiving social validation through these platforms activates the same reward centers in the brain as eating chocolate or winning money. This neurological response explains why many adults find it difficult to disconnect from their devices, constantly checking for notifications even during important activities like work meetings or family dinners. The intermittent reinforcement of unpredictable rewards keeps users coming back, often without conscious awareness of their behavior.

Sleep disruption represents another significant concern linked to social media usage. Many adults report scrolling through feeds late into the night, with the blue light emitted by screens interfering with natural circadian rhythms. The stimulating content encountered during late-night browsing can activate the mind, making it harder to fall asleep and reducing overall sleep quality. Sleep deprivation, in turn, has well-documented negative effects on mood, cognitive function, and mental health.

Despite these challenges, social media is not inherently harmful. The impact largely depends on how individuals use these platforms. Passive consumption of content—simply scrolling and observing without meaningful interaction—has been linked to more negative mental health outcomes. In contrast, active engagement such as posting original content, having genuine conversations, and using platforms to maintain real-world relationships appears to have more positive or neutral effects. Some adults have successfully used social media to find support groups for mental health conditions, connect with old friends who provide emotional support, or discover new hobbies and interests that enhance their wellbeing.

Digital literacy and self-awareness are becoming essential skills for navigating social media’s mental health effects. Experts recommend that adults set intentional boundaries around their usage, such as designated phone-free times, turning off non-essential notifications, and regularly auditing which accounts they follow to ensure their feed promotes positive feelings. Some users have found success with app limiters that track and restrict daily usage time. Additionally, cultivating offline activities and relationships provides balance and perspective, preventing social media from becoming the primary source of social interaction and self-worth.

The relationship between social media and adult mental health continues to evolve as platforms develop new features and society adapts to this relatively recent technology. Understanding both the potential benefits and risks allows adults to make informed decisions about their digital habits, maximizing connection and creativity while protecting their psychological wellbeing. As research in this field progresses, clearer guidelines are emerging to help adults navigate the complex landscape of social media in ways that support rather than undermine their mental health.

Người trưởng thành sử dụng điện thoại kiểm tra mạng xã hội ảnh hưởng đến sức khỏe tâm thần

Người trưởng thành sử dụng điện thoại kiểm tra mạng xã hội ảnh hưởng đến sức khỏe tâm thần

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

The average adult spends more than three hours daily on social media platforms.

-

More than 80% of adults between 25 and 54 years old use at least two social media platforms.

-

LinkedIn has completely replaced traditional job application methods.

-

Instagram was identified as particularly problematic for mental health by UK researchers.

-

All adults experience negative mental health effects from social media usage.

Questions 6-9: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, what makes social media potentially addictive?

- A) The amount of time people spend on platforms

- B) The dopamine-driven feedback loops from likes and comments

- C) The number of friends people have online

- D) The variety of content available

-

What effect does blue light from screens have on users?

- A) It improves concentration

- B) It enhances mood

- C) It disrupts natural sleep patterns

- D) It increases energy levels

-

Which type of social media usage is associated with better mental health outcomes?

- A) Passive scrolling through feeds

- B) Watching videos for hours

- C) Active engagement and genuine conversations

- D) Following celebrity accounts

-

What do experts recommend for managing social media usage?

- A) Deleting all social media accounts

- B) Setting intentional boundaries and phone-free times

- C) Using social media only for work purposes

- D) Limiting usage to one platform only

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

Adults often compare their real lives to the _____ that others post online.

-

The unpredictable rewards from social media create _____ that keeps users returning to check their devices.

-

Many adults engage in _____ late at night, which affects their ability to sleep well.

-

Developing _____ helps adults make better decisions about their social media habits.

PASSAGE 2 – The Psychological Mechanisms Behind Social Media Impact

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The relationship between social media usage and adult mental health operates through several intricate psychological mechanisms that researchers have only begun to fully understand in recent years. While early studies focused primarily on correlation—establishing links between time spent online and reported mental health symptoms—contemporary research has delved deeper into the underlying processes that explain why and how these digital platforms affect psychological wellbeing. This more nuanced understanding reveals that social media’s impact is neither uniformly positive nor negative, but rather depends on complex interactions between platform design, individual psychological vulnerabilities, and patterns of usage.

Social comparison theory, first proposed by psychologist Leon Festinger in 1954, provides a fundamental framework for understanding social media’s psychological impact. This theory suggests that individuals determine their own social and personal worth based on how they stack up against others. Before social media, these comparisons were limited to immediate social circles and occasional media exposure. However, platforms like Instagram and Facebook have created an environment of constant, limitless comparison opportunities. Adults now regularly compare their careers, relationships, physical appearance, and lifestyle choices against carefully curated representations of hundreds or thousands of others. Research by Vogel and colleagues has demonstrated that these upward social comparisons—where individuals compare themselves to those perceived as better off—consistently correlate with lower self-esteem and increased depressive symptoms.

The self-presentation paradox represents another critical psychological dynamic. Social media encourages users to construct idealized digital identities that often diverge significantly from their authentic selves. While this strategic self-presentation can serve positive functions—such as exploring aspects of identity or presenting professionally—it can also create psychological strain. The discrepancy between one’s online persona and actual life experiences may lead to feelings of inauthenticity and fragmentation. Adults who heavily curate their online presence often report experiencing imposter syndrome, feeling that their real selves don’t measure up to the versions they present digitally. Furthermore, maintaining these fabricated images requires continuous effort and monitoring, creating a form of emotional labor that can be mentally exhausting.

Validation-seeking behavior has emerged as a particularly problematic pattern associated with social media use. The architecture of these platforms is explicitly designed to encourage users to seek feedback through likes, comments, shares, and followers. This external validation becomes intertwined with self-worth, creating psychologically vulnerable states where individuals depend on others’ responses to feel good about themselves. Psychologists have noted concerning parallels between this dynamic and dependent personality traits. Studies using fMRI technology have shown that receiving likes activates the nucleus accumbens, the brain region associated with reward processing, while posts that receive less engagement than expected can trigger activity in areas associated with social pain and rejection. This neurobiological reactivity helps explain why social media feedback can have such potent emotional effects.

The phenomenon of “context collapse” adds another layer of complexity. On social media, individuals must navigate presenting themselves to vastly different audiences simultaneously—family members, professional colleagues, casual acquaintances, and complete strangers all inhabit the same digital space. This erosion of traditional social boundaries creates unique pressures, as adults attempt to craft content that is appropriate and appealing across disparate social contexts. The resulting self-censorship and strategic ambiguity can be cognitively demanding and may contribute to feelings of social anxiety. Some users report experiencing performance anxiety when posting, worrying excessively about how different audience segments will interpret their content.

Research has also identified “cyberostracism”—or online exclusion—as a significant source of distress. Adults may experience this through obvious mechanisms like being unfriended or blocked, or more subtle ones like noticing social gatherings they weren’t invited to, or having messages ignored. Neuroimaging studies conducted by Williams and colleagues revealed that social exclusion online activates the same brain regions as physical pain, suggesting that virtual rejection carries real psychological weight. For adults, whose social networks increasingly exist partly or primarily online, these digital exclusions can have meaningful impacts on mental wellbeing and feelings of belonging.

Algorithmic amplification of content represents a less obvious but increasingly recognized factor. Social media platforms use sophisticated algorithms to determine what content users see, designed to maximize engagement rather than wellbeing. These algorithms tend to amplify content that generates strong emotional reactions—particularly anger, outrage, or anxiety—because such content keeps users engaged. Adults exposed to algorithmically-curated feeds heavy in negative or divisive content may experience heightened stress and anxiety, often without recognizing that their emotional responses are being partly shaped by algorithmic choices rather than reflecting an accurate representation of reality. The filter bubble effect can also create echo chambers that reinforce pre-existing beliefs and anxieties while limiting exposure to diverse perspectives that might provide balance.

Cơ chế tâm lý của tác động mạng xã hội đến sức khỏe tinh thần người lớn

Cơ chế tâm lý của tác động mạng xã hội đến sức khỏe tinh thần người lớn

Protective factors exist alongside these risk mechanisms. Adults with strong offline social support, well-developed emotional regulation skills, and secure attachment styles appear more resilient to social media’s potential negative effects. Additionally, metacognitive awareness—the ability to recognize and reflect upon one’s own thought patterns and emotional reactions—serves as a buffer. Adults who can identify when social media use is affecting their mood negatively and adjust their behavior accordingly experience fewer adverse psychological outcomes. This self-regulatory capacity is increasingly recognized as a critical component of digital wellness.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Matching Headings

The passage has nine paragraphs (1-9). Choose the correct heading for paragraphs 2-6 from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

- i. The role of brain chemistry in social media addiction

- ii. How algorithms shape emotional experiences

- iii. Comparing ourselves to others in the digital age

- iv. The challenge of presenting different identities to different audiences

- v. Building resilience against negative effects

- vi. The pain of being excluded online

- vii. The stress of maintaining fake online personas

- viii. Seeking approval through likes and comments

- ix. The historical development of social networking

- Paragraph 2 ___

- Paragraph 3 ___

- Paragraph 4 ___

- Paragraph 5 ___

- Paragraph 6 ___

Questions 19-22: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Early research on social media focused on establishing correlations rather than explaining underlying causes.

-

Social comparison theory was specifically developed to explain social media behavior.

-

Maintaining an idealized online identity requires significant mental effort.

-

All adults who use social media heavily develop imposter syndrome.

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Social media platforms employ 23. that determine which content users see. These systems are designed to increase user engagement rather than promote wellbeing. They tend to show content that generates strong 24. such as anger or anxiety. This can result in users experiencing increased stress without realizing their emotions are being influenced by 25. . Additionally, users may find themselves in 26. where their existing beliefs are reinforced and they receive limited exposure to different viewpoints.

PASSAGE 3 – Neuroscience, Clinical Perspectives, and Future Interventions

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The burgeoning field of digital mental health has prompted neuroscientists and clinical psychologists to investigate the neurobiological substrates underlying social media’s effects on adult psychological functioning. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), have revealed that social media engagement is far from a neutral cognitive activity; rather, it involves complex neural networks associated with reward processing, social cognition, self-referential thinking, and emotional regulation. These findings have profound implications for understanding both the addictive qualities of social platforms and the mechanisms by which they influence mental health outcomes in adult populations.

Neurobiological research conducted by Sherman and colleagues utilizing fMRI has demonstrated that viewing posts with numerous likes activates the ventral striatum, a key component of the brain’s reward circuitry. This region, which is richly innervated by dopaminergic neurons, shows activation patterns remarkably similar to those observed during primary reward processing—such as consuming palatable food or receiving monetary compensation. The anticipatory activation of this system before checking one’s phone for notifications mirrors the neural signature of substance-related craving states, providing a neurobiological rationale for the compulsive checking behaviors many adults report experiencing. Crucially, the variable reward schedule inherent in social media—where the timing and magnitude of social reinforcement are unpredictable—has been shown to produce more robust and persistent behavioral patterns than fixed reward schedules, a phenomenon well-established in behavioral neuroscience literature.

The default mode network (DMN), a collection of brain regions active during self-referential processing and mind-wandering, appears to be significantly modulated by social media usage patterns. Longitudinal studies have revealed that adults who engage in excessive social media use show altered connectivity patterns within the DMN, particularly between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex. These alterations are associated with increased rumination—a cognitive pattern characterized by repetitive, self-focused negative thinking that represents a transdiagnostic risk factor for both depression and anxiety disorders. The bidirectional relationship between social media use and rumination is particularly concerning: social media may facilitate ruminative thinking through constant exposure to comparison-inducing stimuli, while individuals already prone to rumination may be disproportionately drawn to social media as a maladaptive coping strategy for managing negative affect.

Clinical investigations have begun to delineate specific vulnerability profiles that predict which adults are most susceptible to social media’s deleterious mental health effects. Individuals with pre-existing anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety disorder, appear to face a paradoxical situation: while they may initially gravitate toward online social interaction as a less threatening alternative to face-to-face communication, excessive social media use often exacerbates their symptoms over time. The disinhibition effect of online communication may provide temporary relief, but the asynchronous nature of digital interaction prevents the development of real-time social skills and the anxiety habituation that occurs through graduated exposure to feared social situations. Furthermore, the permanence and visibility of online interactions create new anxiety provocations, as individuals worry about how their posts will be perceived and scrutinized over time.

Để hiểu rõ hơn về How to promote mental health for caregivers, nghiên cứu cho thấy rằng các yếu tố bảo vệ tâm lý đóng vai trò quan trọng trong việc giảm thiểu tác động tiêu cực.

The problematic social media use (PSMU) construct has emerged as a clinically relevant framework for understanding pathological engagement with these platforms. PSMU is characterized by six core components adapted from substance addiction criteria: salience (social media becomes the most important activity), mood modification (using platforms to alter emotional states), tolerance (requiring increasing amounts of use to achieve the same effects), withdrawal symptoms (experiencing anxiety or irritability when unable to access platforms), conflict (interpersonal problems arising from usage), and relapse (reverting to excessive use after attempts to reduce it). Psychometric instruments such as the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in identifying adults meeting these criteria. Epidemiological studies suggest that approximately 5-10% of adult users may meet diagnostic thresholds for PSMU, though prevalence varies considerably across cultural contexts and demographic groups.

Intervention strategies grounded in evidence-based psychological frameworks are being developed and tested to mitigate social media’s adverse mental health impacts. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) protocols adapted for digital wellbeing have shown preliminary efficacy in helping adults restructure maladaptive thought patterns related to social media use, challenge distorted social comparisons, and develop behavioral strategies for reducing compulsive checking. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) represent another promising approach; cultivating present-moment awareness and non-judgmental observation of one’s thoughts and urges may help adults recognize and disengage from automatic scrolling behaviors before they trigger negative emotional cascades. A randomized controlled trial by Hunt and colleagues found that limiting social media use to 30 minutes per day for three weeks led to significant reductions in loneliness and depression among young adults, suggesting that structured reduction strategies can yield tangible mental health benefits.

Khi nghiên cứu về Does social media have a positive or negative impact, các nhà khoa học nhận thấy rằng câu trả lời phụ thuộc vào nhiều yếu tố phức tạp và không thể đơn giản hóa thành một kết luận duy nhất.

From a public health perspective, addressing social media’s mental health effects requires multilevel interventions spanning individual, community, and policy domains. Digital literacy education for adults—particularly those who came of age before social media’s ubiquity—is essential for fostering critical engagement with these platforms. Such education should encompass understanding algorithmic curation, recognizing manipulative design features, and developing metacognitive skills for monitoring one’s emotional responses to online content. At the policy level, some experts advocate for platform design reforms that prioritize user wellbeing over engagement metrics, such as removing visible like counts, implementing default usage limits, or redesigning infinite scroll features that capitalize on psychological vulnerabilities. The ethical implications of attention engineering—the deliberate design of technologies to maximize user engagement—have come under increasing scrutiny, with calls for platforms to adopt human-centered design principles that consider long-term psychological consequences rather than merely short-term behavioral metrics.

Emerging therapeutic approaches are leveraging technology itself to promote digital wellbeing. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) delivered via smartphone applications allows researchers and clinicians to track real-time relationships between social media use and mood fluctuations, providing individualized data that can inform personalized intervention strategies. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) use this data to deliver targeted support at moments when individuals are most vulnerable to problematic usage patterns or negative mental health impacts. For instance, a JITAI system might detect when an individual has been scrolling for an extended period and is showing signs of negative affect, then deliver a brief mindfulness exercise or a prompt to engage in an alternative activity. While these technology-assisted interventions are still in relatively early stages of development and validation, they represent a promising avenue for scalable mental health support in an increasingly digital world.

Nghiên cứu khoa học thần kinh về ảnh hưởng mạng xã hội lên não bộ

Nghiên cứu khoa học thần kinh về ảnh hưởng mạng xã hội lên não bộ

The longitudinal trajectory of social media’s mental health effects remains an area requiring sustained empirical attention. As platforms evolve, introducing new features and interaction modalities—such as ephemeral content, augmented reality filters, and algorithm-driven recommendations—their psychological impacts may shift in unpredictable ways. Moreover, cohort effects are likely significant; adults who have integrated social media throughout their adult lives may experience different effects than those who adopted these technologies later in life. Prospective longitudinal studies following diverse adult samples over extended periods are essential for disentangling causal relationships, identifying critical periods of vulnerability or resilience, and understanding how individual differences in personality traits, coping strategies, and social contexts moderate outcomes. Such research will be crucial for developing nuanced, evidence-based guidelines that acknowledge both the risks and benefits inherent in these ubiquitous technologies, ultimately empowering adults to harness social media’s connective potential while safeguarding their psychological wellbeing.

3. Answer Keys – Đáp án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- FALSE

- B

- C

- C

- B

- highlight reels

- intermittent reinforcement

- scrolling through feeds

- digital literacy / self-awareness

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- iii

- vii

- viii

- iv

- vi

- YES

- NO

- YES

- NO

- sophisticated algorithms

- emotional reactions

- algorithmic choices

- echo chambers / filter bubble

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- D

- A

- B

- reward circuitry / reward processing

- rumination

- social anxiety disorder

- mood modification

- 5-10%

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy / CBT

- 30 minutes

- digital literacy education

- Ecological momentary assessment / EMA

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: average adult, more than three hours, daily

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “the average user spending approximately 2.5 hours per day” (người dùng trung bình dành khoảng 2.5 giờ mỗi ngày). 2.5 giờ nhỏ hơn 3 giờ, do đó câu phát biểu “more than three hours” là sai.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: 80%, adults 25-54, at least two platforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “over 80% of this demographic maintains active profiles on at least two platforms” (hơn 80% nhóm dân số này duy trì hồ sơ hoạt động trên ít nhất hai nền tảng). Khớp hoàn toàn với câu phát biểu.

Câu 3: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: LinkedIn, completely replaced, traditional job application

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Bài đọc chỉ đề cập LinkedIn “revolutionized career development” nhưng không nói gì về việc nó thay thế hoàn toàn các phương pháp truyền thống.

Câu 4: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Instagram, problematic, UK researchers, mental health

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: Văn bản nêu “Research conducted by the Royal Society for Public Health in the United Kingdom found that Instagram, in particular, was associated with high levels of anxiety, depression…” cho thấy Instagram được xác định là đặc biệt có vấn đề.

Câu 6: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: potentially addictive

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “The dopamine-driven feedback loops created by likes, comments, and shares have been compared to gambling mechanisms, creating addictive patterns” – vòng phản hồi dopamine từ likes và comments tạo ra tính gây nghiện.

Câu 8: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: better mental health outcomes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn phân biệt rõ: “Passive consumption…linked to more negative mental health outcomes. In contrast, active engagement…appears to have more positive or neutral effects” – tương tác tích cực và cuộc trò chuyện thực sự có kết quả tốt hơn.

Câu 10: highlight reels

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: compare, real lives, others post online

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, giữa đoạn

- Giải thích: Câu gốc: “Adults often find themselves comparing their everyday reality to the highlight reels posted by others” – cụm “highlight reels” là đáp án chính xác.

Câu 13: digital literacy / self-awareness

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: developing, better decisions, social media habits

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, câu đầu

- Giải thích: “Digital literacy and self-awareness are becoming essential skills for navigating social media’s mental health effects” – cả hai từ đều được chấp nhận là đáp án đúng.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: iii (Comparing ourselves to others in the digital age)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Paragraph 2

- Giải thích: Đoạn này tập trung vào “Social comparison theory” và cách mọi người so sánh bản thân với người khác trên mạng xã hội. Các từ khóa như “compare their careers, relationships, physical appearance” và “upward social comparisons” chỉ ra nội dung chính là về việc so sánh.

Câu 15: vii (The stress of maintaining fake online personas)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Paragraph 3

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn bàn về “self-presentation paradox”, “idealized digital identities”, “discrepancy between one’s online persona and actual life” và “emotional labor” của việc duy trì hình ảnh giả tạo trực tuyến.

Câu 16: viii (Seeking approval through likes and comments)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Paragraph 4

- Giải thích: Đoạn này tập trung vào “validation-seeking behavior” và cách người dùng tìm kiếm phản hồi qua likes, comments. Đề cập đến việc “external validation becomes intertwined with self-worth”.

Câu 19: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí: Đoạn 1, câu thứ 2

- Giải thích: “While early studies focused primarily on correlation—establishing links…contemporary research has delved deeper into the underlying processes” khẳng định nghiên cứu ban đầu tập trung vào tương quan.

Câu 20: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “Social comparison theory, first proposed by psychologist Leon Festinger in 1954” – lý thuyết này được đề xuất năm 1954, trước khi có mạng xã hội, do đó không phải được phát triển đặc biệt cho mạng xã hội.

Câu 23: sophisticated algorithms

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí: Đoạn 7, câu đầu

- Giải thích: “Social media platforms use sophisticated algorithms to determine what content users see” – cụm từ chính xác từ bài đọc.

Câu 26: echo chambers / filter bubble

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí: Đoạn 7, cuối đoạn

- Giải thích: “The filter bubble effect can also create echo chambers that reinforce pre-existing beliefs” – cả hai từ đều xuất hiện và có ý nghĩa tương đương trong ngữ cảnh này.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice (câu hỏi về neuroimaging techniques)

- Vị trí: Đoạn 1

- Giải thích: Đoạn đầu đề cập đến “functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET)” như những kỹ thuật được sử dụng để nghiên cứu tác động thần kinh của mạng xã hội.

Câu 32: reward circuitry / reward processing

- Dạng câu hỏi: Note/Table Completion

- Vị trí: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: “viewing posts with numerous likes activates the ventral striatum, a key component of the brain’s reward circuitry” – cụm từ này mô tả chính xác hệ thống được kích hoạt.

Câu 33: rumination

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Vị trí: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: “These alterations are associated with increased rumination—a cognitive pattern characterized by repetitive, self-focused negative thinking” – rumination là khái niệm trung tâm được giải thích chi tiết.

Câu 36: 5-10%

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Vị trí: Đoạn 5, cuối đoạn

- Giải thích: “Epidemiological studies suggest that approximately 5-10% of adult users may meet diagnostic thresholds for PSMU” – con số cụ thể được nêu rõ.

Câu 37: Cognitive-behavioral therapy / CBT

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Vị trí: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) protocols adapted for digital wellbeing have shown preliminary efficacy” – CBT được xác định là phương pháp can thiệp dựa trên bằng chứng.

Câu 38: 30 minutes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Vị trí: Đoạn 6, cuối đoạn

- Giải thích: “limiting social media use to 30 minutes per day for three weeks led to significant reductions in loneliness and depression” – thời gian cụ thể được đề cập trong nghiên cứu.

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| integral | adj | /ˈɪntɪɡrəl/ | không thể thiếu, cần thiết | These platforms have become integral to daily routines | integral part, integral component |

| widespread | adj | /ˈwaɪdspred/ | phổ biến rộng rãi | This widespread adoption has created both opportunities | widespread use, widespread adoption |

| curated | adj | /kjʊəˈreɪtɪd/ | được tuyển chọn, sắp xếp cẩn thận | pressure to present a curated version of oneself | curated content, carefully curated |

| highlight reels | n phrase | /ˈhaɪlaɪt riːlz/ | những khoảnh khắc đẹp nhất được chọn lọc | comparing their reality to the highlight reels posted by others | social media highlight reels |

| FOMO | n | /ˈfəʊməʊ/ | nỗi lo sợ bị bỏ lỡ (fear of missing out) | high levels of anxiety and fear of missing out (FOMO) | experience FOMO, FOMO anxiety |

| dopamine-driven | adj | /ˈdəʊpəmiːn ˈdrɪvən/ | dẫn dắt bởi dopamine | dopamine-driven feedback loops created by likes | dopamine-driven behavior |

| addictive patterns | n phrase | /əˈdɪktɪv ˈpætənz/ | các hành vi gây nghiện | creating addictive patterns of behavior | develop addictive patterns |

| intermittent reinforcement | n phrase | /ˌɪntəˈmɪtənt ˌriːɪnˈfɔːsmənt/ | sự củng cố không đều đặn | The intermittent reinforcement of unpredictable rewards | intermittent reinforcement schedule |

| circadian rhythms | n phrase | /sɜːˈkeɪdiən ˈrɪðəmz/ | nhịp sinh học | interfering with natural circadian rhythms | disrupt circadian rhythms |

| passive consumption | n phrase | /ˈpæsɪv kənˈsʌmpʃən/ | việc tiêu thụ thụ động | Passive consumption of content linked to negative outcomes | passive consumption of media |

| digital literacy | n phrase | /ˈdɪdʒɪtəl ˈlɪtərəsi/ | hiểu biết kỹ thuật số | Digital literacy and self-awareness are essential skills | improve digital literacy |

| intentional boundaries | n phrase | /ɪnˈtenʃənəl ˈbaʊndəriz/ | ranh giới có chủ đích | set intentional boundaries around their usage | establish intentional boundaries |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intricate | adj | /ˈɪntrɪkət/ | phức tạp, rắc rối | intricate psychological mechanisms | intricate details, intricate system |

| underlying | adj | /ˌʌndəˈlaɪɪŋ/ | tiềm ẩn, cơ bản | the underlying processes that explain | underlying causes, underlying factors |

| nuanced | adj | /ˈnjuːɑːnst/ | tinh tế, sâu sắc | This more nuanced understanding reveals | nuanced perspective, nuanced approach |

| vulnerability | n | /ˌvʌlnərəˈbɪləti/ | tính dễ bị tổn thương | individual psychological vulnerabilities | emotional vulnerability, psychological vulnerability |

| stack up against | v phrase | /stæk ʌp əˈɡenst/ | so sánh với | how they stack up against others | stack up against competitors |

| upward social comparisons | n phrase | /ˈʌpwəd ˈsəʊʃəl kəmˈpærɪsənz/ | so sánh xã hội hướng lên | upward social comparisons consistently correlate with lower self-esteem | make upward social comparisons |

| idealized | adj | /aɪˈdɪəlaɪzd/ | được lý tưởng hóa | construct idealized digital identities | idealized image, idealized version |

| discrepancy | n | /dɪsˈkrepənsi/ | sự khác biệt, mâu thuẫn | The discrepancy between online persona and actual life | discrepancy between, significant discrepancy |

| inauthenticity | n | /ˌɪnɔːθenˈtɪsəti/ | tính không chân thực | feelings of inauthenticity and fragmentation | sense of inauthenticity |

| validation-seeking | adj | /ˌvælɪˈdeɪʃən ˈsiːkɪŋ/ | tìm kiếm sự công nhận | Validation-seeking behavior has emerged | validation-seeking behavior |

| intertwined | adj | /ˌɪntəˈtwaɪnd/ | đan xen, gắn chặt | external validation becomes intertwined with self-worth | closely intertwined, intertwined with |

| cyberostracism | n | /ˈsaɪbərˈɒstrəsɪzəm/ | sự tẩy chay trực tuyến | cyberostracism or online exclusion | experience cyberostracism |

| algorithmic amplification | n phrase | /ˌælɡəˈrɪðmɪk ˌæmplɪfɪˈkeɪʃən/ | sự khuếch đại bằng thuật toán | Algorithmic amplification of content | algorithmic amplification of news |

| echo chambers | n phrase | /ˈekəʊ ˈtʃeɪmbəz/ | buồng vang (môi trường chỉ có ý kiến giống nhau) | echo chambers that reinforce pre-existing beliefs | create echo chambers, trapped in echo chambers |

| metacognitive awareness | n phrase | /ˌmetəˈkɒɡnətɪv əˈweənəs/ | nhận thức về nhận thức | metacognitive awareness serves as a buffer | develop metacognitive awareness |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| burgeoning | adj | /ˈbɜːdʒənɪŋ/ | đang phát triển nhanh | The burgeoning field of digital mental health | burgeoning field, burgeoning industry |

| neurobiological substrates | n phrase | /ˌnjʊərəʊbaɪəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈsʌbstreɪts/ | nền tảng thần kinh sinh học | the neurobiological substrates underlying effects | neurobiological substrates of behavior |

| neuroimaging | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊˈɪmɪdʒɪŋ/ | chụp ảnh thần kinh | Advanced neuroimaging techniques | neuroimaging techniques, neuroimaging studies |

| profound implications | n phrase | /prəˈfaʊnd ˌɪmplɪˈkeɪʃənz/ | ý nghĩa sâu sắc | profound implications for understanding | have profound implications |

| ventral striatum | n phrase | /ˈventrəl straɪˈeɪtəm/ | vùng striatum bụng (não) | activates the ventral striatum | ventral striatum activation |

| reward circuitry | n phrase | /rɪˈwɔːd ˈsɜːkɪtri/ | mạch thưởng (trong não) | key component of the brain’s reward circuitry | activate reward circuitry |

| dopaminergic | adj | /ˌdəʊpəmɪˈnɜːdʒɪk/ | liên quan đến dopamine | richly innervated by dopaminergic neurons | dopaminergic neurons, dopaminergic pathways |

| rumination | n | /ˌruːmɪˈneɪʃən/ | sự suy nghĩ lang thang tiêu cực | increased rumination – repetitive, negative thinking | engage in rumination, rumination patterns |

| transdiagnostic | adj | /ˌtrænzdaɪəɡˈnɒstɪk/ | xuyên chẩn đoán | transdiagnostic risk factor for depression | transdiagnostic approach, transdiagnostic factor |

| delineate | v | /dɪˈlɪnieɪt/ | phân định, vạch rõ | delineate specific vulnerability profiles | delineate boundaries, clearly delineate |

| deleterious | adj | /ˌdelɪˈtɪəriəs/ | có hại, bất lợi | deleterious mental health effects | deleterious effects, deleterious impact |

| disinhibition | n | /ˌdɪsɪnhɪˈbɪʃən/ | sự mất kiềm chế | The disinhibition effect of online communication | online disinhibition, disinhibition effect |

| exacerbates | v | /ɪɡˈzæsəbeɪts/ | làm trầm trọng thêm | excessive social media use often exacerbates symptoms | exacerbates the problem, exacerbates symptoms |

| problematic social media use | n phrase | /ˌprɒbləˈmætɪk ˈsəʊʃəl ˈmiːdiə juːs/ | việc sử dụng mạng xã hội có vấn đề | problematic social media use (PSMU) construct | assess problematic social media use |

| salience | n | /ˈseɪliəns/ | tính nổi bật, ưu tiên | salience – social media becomes most important activity | psychological salience, behavioral salience |

| mindfulness-based interventions | n phrase | /ˈmaɪndfəlnəs beɪst ˌɪntəˈvenʃənz/ | can thiệp dựa trên chánh niệm | Mindfulness-based interventions represent promising approach | implement mindfulness-based interventions |

| ecological momentary assessment | n phrase | /ˌiːkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈməʊməntəri əˈsesmənt/ | đánh giá tức thời sinh thái | Ecological momentary assessment delivered via apps | conduct ecological momentary assessment |

| just-in-time adaptive interventions | n phrase | /dʒʌst ɪn taɪm əˈdæptɪv ˌɪntəˈvenʃənz/ | can thiệp thích ứng đúng lúc | JITAIs use data to deliver targeted support | develop just-in-time adaptive interventions |

Kết bài

Chủ đề tác động của mạng xã hội đến sức khỏe tâm thần người trưởng thành không chỉ là một đề tài thời sự mà còn là nội dung xuất hiện thường xuyên trong các kỳ thi IELTS Reading gần đây. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được trải nghiệm đầy đủ cấu trúc của một bài thi IELTS Reading thực tế với 3 passages có độ khó tăng dần từ band 5.0-6.5 đến band 7.0-9.0.

Passage 1 giúp bạn làm quen với chủ đề qua nội dung dễ tiếp cận về cách mạng xã hội ảnh hưởng đến đời sống hàng ngày. Passage 2 đưa bạn vào phân tích sâu hơn về các cơ chế tâm lý như lý thuyết so sánh xã hội và nghịch lý tự thể hiện. Cuối cùng, Passage 3 mang đến góc nhìn khoa học với các nghiên cứu thần kinh và phương pháp can thiệp lâm sàng – đúng với mức độ học thuật cao của IELTS.

Với 40 câu hỏi đa dạng từ True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, Matching Headings đến Summary Completion, bạn đã được luyện tập toàn diện các dạng bài phổ biến nhất. Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin và kỹ thuật paraphrase sẽ giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách tìm đáp án chính xác. Bảng từ vựng với hơn 40 từ quan trọng, phiên âm chuẩn và ví dụ thực tế là tài liệu quý giá để bạn nâng cao vốn từ học thuật.

Tương tự như cách chúng ta tìm hiểu The integration of visual media in health education, việc hiểu sâu về một chủ đề sẽ giúp bạn tự tin hơn khi gặp nội dung tương tự trong kỳ thi thật. Đề thi này không chỉ giúp bạn luyện kỹ năng đọc mà còn cung cấp kiến thức thực tế về một vấn đề xã hội đương đại.

Hãy sử dụng bộ đề này như một công cụ đánh giá trình độ hiện tại và xác định những kỹ năng cần cải thiện. Thực hành đúng cách với việc tuân thủ thời gian quy định cho mỗi passage sẽ giúp bạn xây dựng kỹ năng quản lý thời gian hiệu quả – yếu tố then chốt để đạt band điểm cao trong IELTS Reading. Chúc bạn ôn tập tốt và đạt kết quả như mong muốn!

[…] bối cảnh đó, để hiểu rõ hơn về mental health effects of social media on adults, cần nhận thấy rằng công nghệ hiện đại đã tạo ra một môi trường hoàn […]

[…] with the downregulation of physiological and mental processes necessary for sleep initiation. Mental health effects of social media on adults explores how constant digital engagement affects our psychological well-being beyond sleep […]