Chủ đề về Psychological Effects Of Social Isolation (tác động tâm lý của sự cô lập xã hội) xuất hiện với tần suất ngày càng cao trong các kỳ thi IELTS Reading gần đây, đặc biệt sau đại dịch COVID-19. Đây là một chủ đề thuộc lĩnh vực tâm lý học – xã hội học, thường xuất hiện ở Passage 2 hoặc Passage 3 với độ khó từ trung bình đến nâng cao.

Trong bài viết này, bạn sẽ được thực hành với một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh gồm 3 passages theo đúng format thi thật, từ mức độ dễ đến khó. Bộ đề bao gồm đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với các dạng câu hỏi đa dạng như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và nhiều dạng khác. Sau mỗi passage, bạn sẽ tìm thấy đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin, cách paraphrase và chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với cấu trúc bài thi thật, rèn luyện kỹ năng đọc hiểu học thuật, mở rộng vốn từ vựng chuyên ngành và nâng cao khả năng quản lý thời gian – yếu tố then chốt để đạt band điểm mục tiêu.

Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, không bị trừ điểm khi sai. Điểm số sau đó được quy đổi thành thang band từ 1-9.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó thấp, câu hỏi tương đối đơn giản)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình, yêu cầu phân tích sâu hơn)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao nhất, nội dung phức tạp)

Lưu ý dành 2-3 phút cuối để chuyển đáp án vào Answer Sheet. Trong bài thi thật, bạn không có thêm thời gian cho việc này.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không được nhắc đến

- Yes/No/Not Given – Xác định ý kiến của tác giả

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features – Nối thông tin với đặc điểm

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Growing Concern of Loneliness in Modern Society

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Loneliness has become one of the most pressing public health concerns of the 21st century. While humans have always experienced periods of social isolation, the modern world presents unique challenges that make loneliness more prevalent than ever before. Understanding the psychological effects of being disconnected from others is crucial for developing effective interventions and support systems.

Social isolation refers to the objective state of having minimal contact with other people, while loneliness is the subjective feeling of being alone or disconnected, regardless of the amount of social contact one has. A person can be surrounded by others yet still feel profoundly lonely, just as someone living alone might feel perfectly content with their social connections. This distinction is important because it highlights that loneliness is primarily about the quality rather than quantity of social relationships.

Research has shown that prolonged social isolation can trigger a range of psychological responses. In the short term, people who experience isolation often report feelings of sadness, anxiety, and restlessness. These emotions are actually adaptive responses that evolved to motivate humans to reconnect with their social groups, much like hunger motivates us to seek food. Our ancestors who felt distressed when separated from their tribe were more likely to rejoin the group and survive, passing on these traits to future generations.

However, when isolation extends over longer periods, the psychological effects become more serious. Studies conducted by social psychologists have found that chronic loneliness is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety disorders. People who remain isolated for months or years often develop negative thought patterns, becoming more suspicious of others and interpreting social situations in pessimistic ways. This creates a vicious cycle: loneliness makes people more socially anxious, which causes them to withdraw further, leading to even deeper isolation.

The impact of social isolation on cognitive function is another area of growing concern. Research published in leading psychology journals has demonstrated that people experiencing prolonged loneliness show decreased performance on tasks requiring attention, memory, and decision-making. One landmark study followed over 2,000 adults for ten years and found that those who reported feeling lonely at the beginning of the study experienced faster cognitive decline compared to their socially connected peers, even after accounting for factors like age, education, and physical health.

Sleep disturbances represent another common psychological effect of social isolation. Lonely individuals frequently report difficulty falling asleep, frequent night wakings, and poor sleep quality overall. Scientists believe this may be linked to an evolutionary survival mechanism: when our ancestors were separated from their protective social groups, staying alert through the night increased their chances of survival against predators. Today, this same mechanism may cause isolated individuals to experience hypervigilance that interferes with restful sleep.

The relationship between social isolation and self-esteem is particularly noteworthy. People who lack regular positive social interactions often begin to internalize their isolation, believing that something is fundamentally wrong with them. This self-blame can erode self-worth and create feelings of shame about being alone. Young adults seem especially vulnerable to this effect, possibly because they are at a developmental stage where peer acceptance and social belonging play crucial roles in identity formation.

Interestingly, not everyone responds to isolation in the same way. Individual differences in personality traits significantly influence how people cope with being alone. Those with introverted personalities generally find isolation less distressing than extroverts, who draw energy from social interaction. Additionally, people with strong coping skills and internal resources—such as hobbies, creative pursuits, or spiritual practices—tend to weather periods of isolation with fewer negative psychological effects.

Technology has created a paradoxical situation regarding social isolation. While digital communication tools theoretically make it easier than ever to stay connected, they may also contribute to feelings of loneliness. Virtual interactions often lack the depth and intimacy of face-to-face contact. Social media can create the illusion of connection while actually increasing feelings of isolation, especially when people compare their lives unfavorably to the carefully curated images others present online. For those already experiencing loneliness, this comparison can deepen their sense of being disconnected from others.

Understanding these psychological effects is the first step toward addressing the loneliness epidemic. Mental health professionals now recognize social isolation as a significant risk factor for various psychological problems and are developing targeted interventions. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy to address negative thought patterns, social skills training to help people build connections, and community-based programs that bring isolated individuals together around shared interests. As research in this field continues to expand, we are gaining valuable insights into how to protect mental health in an increasingly disconnected world.

Người đàn ông cô đơn ngồi một mình thể hiện tác động tâm lý của sự cô lập xã hội

Người đàn ông cô đơn ngồi một mình thể hiện tác động tâm lý của sự cô lập xã hội

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

1. According to the passage, what is the main difference between social isolation and loneliness?

A. Social isolation is more serious than loneliness

B. Loneliness is about subjective feelings while isolation is objective

C. Social isolation only affects elderly people

D. Loneliness always results from social isolation

2. Why did feelings of distress when separated from groups develop in humans?

A. To punish individuals who left the tribe

B. To make people feel uncomfortable

C. To encourage reconnection with social groups for survival

D. To help people enjoy being alone

3. What happens when social isolation continues for extended periods?

A. People become more trusting of others

B. Individuals develop more positive thinking patterns

C. People become suspicious and pessimistic about social situations

D. Social anxiety decreases naturally over time

4. The ten-year study mentioned in the passage found that lonely people experienced:

A. Improved memory function

B. Better decision-making abilities

C. Faster decline in cognitive abilities

D. No changes in mental performance

5. According to the passage, why might isolated people have trouble sleeping?

A. They watch too much television at night

B. An evolutionary mechanism makes them stay alert

C. They exercise too much during the day

D. They consume too much caffeine

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

6. Everyone experiences the psychological effects of isolation in exactly the same way.

7. Introverted people generally find isolation less difficult than extroverted people.

8. Social media always improves people’s sense of connection with others.

9. Mental health professionals have developed specific treatments for social isolation.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

10. Chronic loneliness creates a __ where anxiety leads to further withdrawal from social contact.

11. People who lack positive social contact may develop __ about being alone.

12. Those with strong __ such as hobbies or spiritual practices cope better with isolation.

13. Virtual interactions often do not have the __ of meeting people face-to-face.

PASSAGE 2 – Neurobiological Mechanisms Behind Social Isolation

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The psychological impact of social isolation extends far beyond subjective feelings of loneliness and melancholy; it involves complex neurobiological mechanisms that fundamentally alter brain structure and function. Recent advances in neuroscience and neuroimaging technology have enabled researchers to observe precisely how periods of social deprivation affect the human brain, revealing connections between isolation and changes in neural pathways, neurotransmitter systems, and even genetic expression. These discoveries are revolutionizing our understanding of why social connection is not merely desirable but neurologically essential for human well-being.

At the molecular level, social isolation triggers significant changes in the brain’s chemical messengers. Dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with reward and motivation, shows markedly reduced activity in socially isolated individuals. Functional MRI studies have demonstrated that the reward centers of the brain—particularly the ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex—exhibit diminished activation when isolated people view images of social interaction or contemplate engaging with others. This neurochemical dampening helps explain why chronically lonely individuals often lose interest in socializing: their brains literally find social interaction less rewarding, creating a neurological barrier to reconnection.

Serotonin, another crucial neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, similarly becomes dysregulated during extended isolation. Lower serotonin levels are consistently observed in both animal models of social deprivation and human subjects reporting chronic loneliness. This biochemical alteration contributes directly to the depressive symptoms frequently accompanying isolation, including anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure), fatigue, and hopelessness. Interestingly, the relationship appears bidirectional: isolation reduces serotonin, but low serotonin also increases social avoidance behaviors, further entrenching the isolated state.

The brain’s stress response system undergoes particularly dramatic changes during social isolation. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs our response to threats and challenges, becomes hyperactive in isolated individuals. This results in chronically elevated levels of cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. While short-term cortisol elevation is adaptive—preparing us to deal with immediate challenges—sustained elevation causes neurotoxic effects. Studies have shown that prolonged high cortisol levels can damage the hippocampus, a brain region critical for memory formation and emotional regulation, potentially explaining the cognitive deficits observed in chronically lonely people.

Brain structure itself appears to be malleable in response to social connection or isolation, a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity. Longitudinal neuroimaging studies tracking individuals over several years have revealed that those experiencing persistent social isolation show reduced gray matter volume in several key brain regions. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like planning and decision-making, tends to show particularly pronounced atrophy. Similarly, regions within the temporal lobes involved in social cognition—understanding others’ mental states and interpreting social cues—also demonstrate volumetric reductions following extended periods of isolation.

The default mode network (DMN), a set of interconnected brain regions active during self-referential thinking and social cognition, shows altered patterns of activity in isolated individuals. Typically, the DMN activates when we think about ourselves, imagine others’ perspectives, or mentally simulate social scenarios. In people experiencing chronic loneliness, however, the DMN often becomes hyperactive, leading to excessive rumination and self-focused attention. This neurological pattern correlates with the negative cognitive spirals characteristic of isolation-induced depression: repetitive, intrusive thoughts about one’s social inadequacies or past social failures.

Emerging research into epigenetics—how environmental factors influence gene expression without changing DNA sequences—has revealed that social isolation can literally affect which genes are turned on or off. Studies examining gene transcription patterns in lonely versus socially connected individuals have found systematic differences in genes regulating inflammatory responses and immune function. Isolated individuals show upregulation (increased activity) of pro-inflammatory genes and downregulation (decreased activity) of genes involved in antiviral responses and antibody production. This molecular signature of loneliness may explain why socially isolated people face elevated risks not only for mental health problems but also for physical illnesses and infections.

The mirror neuron system, which enables us to understand and empathize with others by internally simulating their experiences, may also be affected by prolonged isolation. These specialized neurons, distributed throughout regions involved in motor control, sensation, and emotion, fire both when we perform actions ourselves and when we observe others performing them. Some neuroscientists hypothesize that lack of social interaction might lead to reduced activation or even atrophy of this system, potentially impairing empathic abilities and making social reconnection more challenging. While this theory remains speculative and requires further investigation, it offers a compelling neurobiological explanation for why isolated individuals sometimes struggle to interpret social situations accurately.

Recent investigations using resting-state functional connectivity analysis have uncovered that isolation alters how different brain regions communicate with each other. Specifically, isolated individuals show reduced connectivity between the amygdala (involved in processing fear and threats) and regions of the prefrontal cortex responsible for emotional regulation. This disconnection may explain why lonely people often experience heightened social anxiety and difficulty managing negative emotions: the brain’s regulatory circuits literally become less coordinated. One particularly innovative study used machine learning algorithms to analyze brain connectivity patterns and successfully predicted whether individuals experienced high or low levels of loneliness with over 80% accuracy, demonstrating robust neural correlates of the subjective experience of isolation.

These neurobiological findings carry important implications for intervention. If social isolation produces measurable changes in brain chemistry, structure, and connectivity, then interventions that successfully reduce loneliness should reverse these changes. Preliminary research supports this hypothesis: studies examining the brains of previously isolated individuals who underwent social skills training or joined community support groups show normalization of neurotransmitter levels, restoration of gray matter volume in affected regions, and improved connectivity patterns. This neural plasticity offers hope that even after extended periods of isolation, the brain retains the capacity to heal and adapt when social connection is restored.

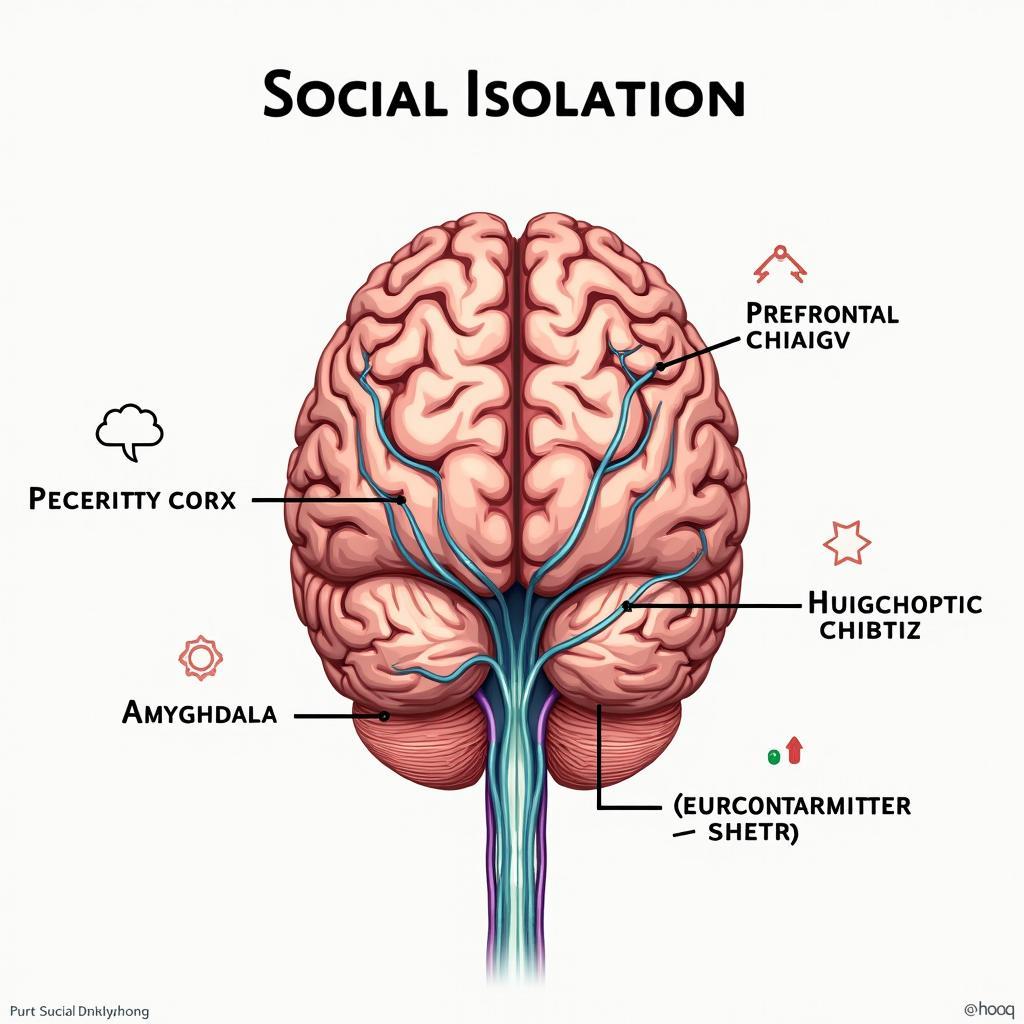

Hình ảnh chụp cắt lớp não bộ minh họa cơ chế thần kinh của sự cô lập xã hội

Hình ảnh chụp cắt lớp não bộ minh họa cơ chế thần kinh của sự cô lập xã hội

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in the passage?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

14. Neuroimaging technology has made it possible to see how isolation affects the brain.

15. All neurotransmitters increase their activity during periods of social isolation.

16. The relationship between serotonin and isolation works in only one direction.

17. Damage to the hippocampus can explain some cognitive problems in lonely people.

18. The theory about mirror neurons and isolation has been conclusively proven.

Questions 19-23: Matching Headings

The passage has ten paragraphs (1-10). Choose the correct heading for paragraphs 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. The role of stress hormones in isolation

ii. How genes respond to social connection

iii. Changes in brain reward systems

iv. The possibility of neurological recovery

v. Understanding others through neural mirroring

vi. Excessive self-focused thinking patterns

vii. Communication between brain regions

viii. The impact on mood-regulating chemicals

ix. Structural changes in the brain

x. Environmental influences on behavior

19. Paragraph 2

20. Paragraph 4

21. Paragraph 6

22. Paragraph 8

23. Paragraph 10

Questions 24-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Social isolation affects the brain through multiple mechanisms. The 24. __ shows unusual activity patterns in lonely people, leading to excessive rumination. Research in epigenetics has found that isolation influences 25. __ without changing DNA. Studies show that isolation reduces 26. __ between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, making emotional regulation more difficult.

PASSAGE 3 – Sociocultural Dimensions and Interventions for Social Isolation

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The psychological ramifications of social isolation cannot be adequately understood through a purely individualistic lens; rather, they must be contextualized within broader sociocultural frameworks that shape how isolation is experienced, interpreted, and addressed across different populations. Contemporary scholarship in social psychology, anthropology, and public health increasingly recognizes that the subjective phenomenology of loneliness and the objective circumstances producing isolation are profoundly mediated by cultural values, social structures, economic systems, and historical contingencies. This multidimensional perspective reveals that what constitutes social connection, how isolation is stigmatized, and which populations face disproportionate vulnerability varies considerably across cultural contexts, necessitating culturally-responsive interventions rather than universalistic approaches.

Individualistic cultures, predominantly found in Western industrialized nations, tend to emphasize personal autonomy, self-reliance, and individual achievement over communal obligations and collective identity. Within these cultural frameworks, social relationships are often conceptualized as voluntary associations based on personal compatibility and mutual benefit rather than as ascribed roles determined by kinship or community membership. Consequently, individuals in such societies may experience particular vulnerability to isolation as geographic mobility, career demands, and the nuclear family structure attenuate traditional social support networks. Research comparing loneliness prevalence across nations suggests that countries scoring higher on individualism indices paradoxically report higher rates of subjective loneliness, despite generally having greater material wealth and more extensive communication infrastructure. This counterintuitive finding underscores that technological connectivity cannot substitute for the deep, multifaceted social embeddedness characteristic of more collectivist societies.

In contrast, collectivist cultures, more prevalent in Asian, African, and Latin American contexts, prioritize group harmony, interdependence, and role fulfillment within hierarchical social structures. Here, social isolation carries different connotations and consequences. While the buffering effects of strong kinship networks and communal living arrangements may protect against isolation, individuals who fall outside normative social roles—whether due to non-conformity, migration, disability, or other factors—may experience particularly acute marginalization. Furthermore, in cultures where emotional restraint and self-sacrifice for the collective are valued, the subjective distress of loneliness may be less readily articulated or legitimized as warranting intervention, potentially leaving isolated individuals without adequate support despite the existence of strong community structures.

The digital revolution has introduced novel dimensions to the social isolation phenomenon that transcend traditional cultural boundaries while simultaneously interacting with them in complex ways. Virtual communities and online social networks have created unprecedented opportunities for connection across geographic distances, enabling individuals with niche interests, marginalized identities, or mobility limitations to forge meaningful relationships that might be impossible in their immediate physical environments. Simultaneously, however, the algorithmic curation of online social experiences, the asynchronous nature of digital communication, and the performative aspects of social media presence introduce new potential pathways to isolation. Recent longitudinal studies employing experience sampling methods suggest that passive social media consumption—scrolling through others’ content without active engagement—consistently predicts increased loneliness over time, whereas active digital interaction involving reciprocal communication shows more ambiguous effects depending on whether it supplements or substitutes for face-to-face contact.

Structural inequalities create differential exposure to isolation risks across demographic groups. Socioeconomic marginalization compounds isolation through multiple mechanisms: precarious employment disrupts stable social relationships, residential instability prevents community integration, and financial constraints limit access to social spaces and activities. Elderly populations face age-segregated living arrangements and the attrition of social networks through death and disability, while younger cohorts confront the atomizing effects of competitive educational and labor markets. LGBTQ+ individuals, particularly in contexts lacking legal protections or cultural acceptance, frequently experience family estrangement and community rejection, leading to elevated isolation rates. Disability, whether physical or cognitive, creates isolation through both architectural barriers excluding individuals from public spaces and the social stigma that discourages inclusion. These patterns demonstrate that isolation is not randomly distributed but rather systematically produced by intersecting systems of marginalization.

Contemporary intervention approaches increasingly recognize this heterogeneity in isolation experiences. Targeted programs addressing specific populations—such as peer support groups for bereaved widowers, affirming communities for sexual minorities, or accessible social venues for disabled individuals—show greater efficacy than generic socialization opportunities that may inadvertently reproduce the very exclusions that produced isolation. Community-based participatory research methodologies, involving isolated individuals themselves in designing interventions, have yielded innovative approaches including intergenerational mentoring programs, skill-sharing cooperatives, and community gardens that foster connection through purposeful collaboration rather than artificial socialization.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions specifically adapted for loneliness target the maladaptive cognitions that perpetuate isolation. These include negative self-schemas (“I am fundamentally unlikeable”), hostile attribution biases (interpreting ambiguous social cues as rejecting), and catastrophizing about social outcomes. Metacognitive approaches additionally address rumination patterns and self-focused attention that interfere with authentic social engagement. Clinical trials comparing modified CBT protocols to standard psychotherapy or waitlist controls consistently demonstrate moderate to large effect sizes in reducing both subjective loneliness and objective isolation, with gains maintained at follow-up assessments extending to two years. Importantly, these interventions appear most effective when combined with behavioral activation components that provide structured opportunities for social exposure, addressing both the cognitive barriers and situational constraints maintaining isolation.

Policy-level interventions recognize that isolation is partially produced by societal organization rather than individual deficits. Urban planning initiatives emphasizing walkable neighborhoods, mixed-use development, and public spaces facilitating spontaneous interaction can create built environments conducive to social connection. Universal programs such as community centers, public libraries, and subsidized cultural venues provide neutral spaces where diverse individuals can encounter each other without the economic barriers of commercial establishments. Some jurisdictions have appointed Ministers of Loneliness or equivalent positions to coordinate cross-sector initiatives addressing isolation, recognizing that effective responses require integration across healthcare, housing, transportation, employment, and recreation domains. Early evaluations of such comprehensive approaches suggest promising results, though methodological challenges in attributing population-level outcomes to specific policy changes complicate definitive assessment.

The medicalization of loneliness presents both opportunities and risks. Framing isolation as a public health crisis comparable to smoking or obesity has mobilized resources and legitimized suffering previously dismissed as personal failing. However, critics argue this framework pathologizes normal human experiences, individualizes problems with fundamentally social etiologies, and deflects attention from the structural changes necessary to create genuinely inclusive societies. The prescription of medications for isolation-associated depression or anxiety treats symptoms while potentially substituting pharmacological intervention for the authentic social connection that addresses root causes. Balancing the utility of medical frameworks in securing resources and validating distress against the risks of reductionism and depoliticization remains an ongoing tension in isolation research and practice.

Ultimately, addressing the psychological effects of social isolation requires multilevel interventions simultaneously targeting individual capacities, interpersonal processes, community structures, and societal systems. No single intervention modality proves universally effective across diverse contexts and populations; rather, flexible, integrative approaches responsive to specific needs and circumstances show greatest promise. As social isolation increasingly represents not merely an individual misfortune but a systemic feature of contemporary life in many societies, the challenge becomes not simply treating isolated individuals but fundamentally reimagining social organization to prioritize human connection as essential infrastructure alongside material necessities. Chủ đề về how to support mental health in older adults có mối liên hệ mật thiết với vấn đề cô lập xã hội, đặc biệt trong bối cảnh già hóa dân số toàn cầu. Such transformative vision requires sustained commitment from researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and communities working collaboratively toward societies where meaningful connection becomes accessible to all.

Chương trình can thiệp cộng đồng chống cô lập xã hội với nhiều thế hệ tham gia

Chương trình can thiệp cộng đồng chống cô lập xã hội với nhiều thế hệ tham gia

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

27. According to the passage, individualistic cultures experience higher loneliness rates because:

A. They have less advanced technology

B. Geographic mobility and nuclear families weaken traditional support networks

C. People in these cultures prefer to be alone

D. They have stricter social rules

28. In collectivist cultures, social isolation is:

A. Completely prevented by strong kinship networks

B. More common than in individualistic cultures

C. Particularly severe for those outside normative social roles

D. Not recognized as a problem

29. Passive social media consumption is associated with:

A. Decreased loneliness over time

B. Increased loneliness over time

C. No effect on loneliness

D. Better face-to-face relationships

30. The passage suggests that cognitive-behavioral interventions work best when:

A. Used alone without other treatments

B. Combined with opportunities for social exposure

C. Applied only to elderly populations

D. Focused exclusively on changing thoughts

31. Critics of the medicalization of loneliness argue that it:

A. Provides too many resources for isolated people

B. Successfully addresses structural causes of isolation

C. Treats problems with social causes as individual pathology

D. Reduces the stigma around medication

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each population group (32-36) with the correct isolation risk factor (A-H).

Population Groups:

32. Elderly populations

33. LGBTQ+ individuals

34. People with disabilities

35. Low-income individuals

36. Young people in competitive markets

Risk Factors:

A. Family estrangement and community rejection

B. Architectural barriers and social stigma

C. Age-segregated living and network attrition

D. Precarious employment and residential instability

E. Excessive technology use

F. Lack of education

G. Atomizing effects of competitive environments

H. Cultural differences

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What type of research methodology involves isolated individuals in designing their own interventions?

38. What are the three examples of maladaptive cognitions mentioned that perpetuate isolation?

39. What type of urban planning creates environments that encourage spontaneous social interaction?

40. Some governments have appointed what position to coordinate efforts against isolation?

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- C

- C

- C

- B

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- vicious cycle

- feelings of shame / shame

- internal resources / coping skills

- depth and intimacy / intimacy

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- YES

- NO

- NO

- YES

- NO

- iii

- i

- vi

- v

- iv

- default mode network

- gene expression

- reduced connectivity

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- B

- B

- C

- C

- A

- B

- D

- G

- Community-based participatory research

- negative self-schemas, hostile attribution biases, catastrophizing (any three in any order)

- walkable neighborhoods / mixed-use development

- Ministers of Loneliness

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main difference, social isolation, loneliness

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nêu rõ “Social isolation refers to the objective state of having minimal contact with other people, while loneliness is the subjective feeling of being alone”. Đây là sự paraphrase của đáp án B: loneliness liên quan đến cảm giác chủ quan (subjective feelings) còn isolation là trạng thái khách quan (objective).

Câu 2: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: feelings of distress, separated from groups, develop

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn giải thích “These emotions are actually adaptive responses that evolved to motivate humans to reconnect with their social groups”. Từ “motivate humans to reconnect” được paraphrase thành “encourage reconnection” trong đáp án C. Mục đích là để sinh tồn (survival).

Câu 3: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: isolation continues, extended periods

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ ra “People who remain isolated for months or years often develop negative thought patterns, becoming more suspicious of others and interpreting social situations in pessimistic ways”. Đây chính là đáp án C với paraphrase: suspicious = suspicious, pessimistic = pessimistic about social situations.

Câu 4: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: ten-year study, lonely people experienced

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Nghiên cứu cho thấy “those who reported feeling lonely at the beginning of the study experienced faster cognitive decline”. Cụm “faster cognitive decline” = “faster decline in cognitive abilities” trong đáp án C.

Câu 6: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: everyone, experiences, exactly the same way

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài đọc khẳng định “not everyone responds to isolation in the same way” và “Individual differences in personality traits significantly influence how people cope”. Điều này mâu thuẫn trực tiếp với câu phát biểu nên đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 7: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: introverted people, find isolation less difficult, extroverted

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Câu trong bài “Those with introverted personalities generally find isolation less distressing than extroverts” khớp chính xác với phát biểu. “Less distressing” = “less difficult”.

Câu 9: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: mental health professionals, developed, specific treatments

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Đoạn cuối nêu “Mental health professionals now recognize social isolation as a significant risk factor… and are developing targeted interventions. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy… social skills training… and community-based programs”. “Targeted interventions” = “specific treatments”.

Câu 10: vicious cycle

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: chronic loneliness, anxiety, withdrawal

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài viết sử dụng chính xác cụm từ “This creates a vicious cycle: loneliness makes people more socially anxious, which causes them to withdraw further”.

Câu 11: feelings of shame / shame

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: lack positive social contact, being alone

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nêu “This self-blame can erode self-worth and create feelings of shame about being alone”. Cả “feelings of shame” hoặc “shame” đều chấp nhận được.

Câu 13: depth and intimacy / intimacy

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: virtual interactions, face-to-face contact

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Câu gốc là “Virtual interactions often lack the depth and intimacy of face-to-face contact”. Có thể dùng cả cụm “depth and intimacy” hoặc chỉ “intimacy”.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: neuroimaging technology, see how isolation affects brain

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Tác giả khẳng định “Recent advances in neuroscience and neuroimaging technology have enabled researchers to observe precisely how periods of social deprivation affect the human brain”. Đây rõ ràng là quan điểm đồng tình của tác giả.

Câu 15: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all neurotransmitters, increase, social isolation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết cho thấy dopamine “shows markedly reduced activity” và serotonin “becomes dysregulated” với “lower serotonin levels”. Điều này mâu thuẫn với việc tất cả neurotransmitters đều tăng, do đó đáp án là NO.

Câu 16: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: serotonin, isolation, one direction

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Tác giả nêu rõ “the relationship appears bidirectional: isolation reduces serotonin, but low serotonin also increases social avoidance behaviors”. Từ “bidirectional” mâu thuẫn với “only one direction”.

Câu 17: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: damage to hippocampus, cognitive problems

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Tác giả giải thích “prolonged high cortisol levels can damage the hippocampus… potentially explaining the cognitive deficits observed in chronically lonely people”. Đây là quan điểm rõ ràng của tác giả.

Câu 19: iii (Changes in brain reward systems)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Đoạn này tập trung vào dopamine và “reward centers of the brain” với các cụm từ như “ventral striatum”, “prefrontal cortex”, “diminished activation” khi xem hình ảnh tương tác xã hội. Tiêu đề iii phù hợp nhất.

Câu 20: i (The role of stress hormones in isolation)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: Đoạn này thảo luận về “HPA axis”, “cortisol” (stress hormone), và tác động của “chronically elevated cortisol levels”. Đây rõ ràng là về vai trò của hormone stress.

Câu 24: default mode network

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: unusual activity patterns, rumination

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 1-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu “The default mode network… shows altered patterns of activity in isolated individuals” và “becomes hyperactive, leading to excessive rumination”. Phải ghi chính xác “default mode network”.

Câu 25: gene expression

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: epigenetics, influences, without changing DNA

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn định nghĩa epigenetics là “how environmental factors influence gene expression without changing DNA sequences”.

Câu 26: reduced connectivity

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: isolation, amygdala, prefrontal cortex

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ ra “isolated individuals show reduced connectivity between the amygdala… and regions of the prefrontal cortex”.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: individualistic cultures, higher loneliness rates

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết giải thích “individuals in such societies may experience particular vulnerability to isolation as geographic mobility, career demands, and the nuclear family structure attenuate traditional social support networks”. Đáp án B paraphrase chính xác ý này.

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: collectivist cultures, social isolation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nêu “individuals who fall outside normative social roles… may experience particularly acute marginalization”. Từ “particularly acute” = “particularly severe” trong đáp án C.

Câu 29: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: passive social media consumption, associated with

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Nghiên cứu cho thấy “passive social media consumption… consistently predicts increased loneliness over time”. Đây là đáp án B với paraphrase đơn giản.

Câu 30: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: cognitive-behavioral interventions, work best

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: Bài viết kết luận “these interventions appear most effective when combined with behavioral activation components that provide structured opportunities for social exposure”. “Structured opportunities for social exposure” = “opportunities for social exposure” trong đáp án B.

Câu 31: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: critics, medicalization of loneliness, argue

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Các nhà phê bình cho rằng “this framework pathologizes normal human experiences, individualizes problems with fundamentally social etiologies”. “Individualizes problems with social etiologies” được paraphrase thành “treats problems with social causes as individual pathology” trong đáp án C.

Câu 32: C (Age-segregated living and network attrition)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu rõ “Elderly populations face age-segregated living arrangements and the attrition of social networks through death and disability”.

Câu 33: A (Family estrangement and community rejection)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: Với LGBTQ+ individuals, bài viết chỉ ra “frequently experience family estrangement and community rejection, leading to elevated isolation rates”.

Câu 34: B (Architectural barriers and social stigma)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: Đối với người khuyết tật, “Disability… creates isolation through both architectural barriers excluding individuals from public spaces and the social stigma that discourages inclusion”.

Câu 37: Community-based participatory research

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: research methodology, isolated individuals, designing interventions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu “Community-based participatory research methodologies, involving isolated individuals themselves in designing interventions”. Cần viết chính xác cụm từ này.

Câu 38: negative self-schemas, hostile attribution biases, catastrophizing

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: three examples, maladaptive cognitions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Ba loại được liệt kê rõ ràng: “negative self-schemas”, “hostile attribution biases”, và “catastrophizing”. Có thể ghi theo bất kỳ thứ tự nào.

Câu 40: Ministers of Loneliness

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: governments appointed, position, coordinate efforts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết đề cập “Some jurisdictions have appointed Ministers of Loneliness or equivalent positions to coordinate cross-sector initiatives”.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| social isolation | n | /ˈsəʊʃəl ˌaɪsəˈleɪʃən/ | sự cô lập xã hội | Social isolation refers to the objective state of having minimal contact | prolonged social isolation, experience social isolation |

| public health concern | n | /ˈpʌblɪk helθ kənˈsɜːn/ | vấn đề sức khỏe cộng đồng | Loneliness has become one of the most pressing public health concerns | major public health concern, growing public health concern |

| adaptive response | n | /əˈdæptɪv rɪˈspɒns/ | phản ứng thích nghi | These emotions are actually adaptive responses | evolutionary adaptive response, develop adaptive responses |

| vicious cycle | n | /ˈvɪʃəs ˈsaɪkəl/ | vòng luẩn quẩn | This creates a vicious cycle | break the vicious cycle, trapped in a vicious cycle |

| cognitive function | n | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˈfʌŋkʃən/ | chức năng nhận thức | The impact of social isolation on cognitive function | impaired cognitive function, maintain cognitive function |

| cognitive decline | n | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv dɪˈklaɪn/ | suy giảm nhận thức | Those who reported feeling lonely experienced faster cognitive decline | rapid cognitive decline, prevent cognitive decline |

| sleep disturbances | n | /sliːp dɪˈstɜːbənsɪz/ | rối loạn giấc ngủ | Sleep disturbances represent another common psychological effect | chronic sleep disturbances, suffer from sleep disturbances |

| self-esteem | n | /ˌself ɪˈstiːm/ | lòng tự trọng | The relationship between social isolation and self-esteem | low self-esteem, boost self-esteem, damage self-esteem |

| coping skills | n | /ˈkəʊpɪŋ skɪlz/ | kỹ năng đối phó | People with strong coping skills tend to weather periods of isolation | develop coping skills, effective coping skills |

| virtual interactions | n | /ˈvɜːtʃuəl ˌɪntərˈækʃənz/ | tương tác ảo | Virtual interactions often lack the depth and intimacy | rely on virtual interactions, increase virtual interactions |

| mental health professionals | n | /ˈmentl helθ prəˈfeʃənəlz/ | chuyên gia sức khỏe tâm thần | Mental health professionals now recognize social isolation | consult mental health professionals |

| social skills training | n | /ˈsəʊʃəl skɪlz ˈtreɪnɪŋ/ | đào tạo kỹ năng xã hội | These include social skills training to help people build connections | undergo social skills training, provide social skills training |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| neurobiological mechanisms | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊbaɪəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˈmekənɪzəmz/ | cơ chế thần kinh sinh học | The psychological impact involves complex neurobiological mechanisms | underlying neurobiological mechanisms, study neurobiological mechanisms |

| neuroimaging technology | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊˈɪmɪdʒɪŋ tekˈnɒlədʒi/ | công nghệ chụp hình não | Recent advances in neuroimaging technology have enabled researchers | advanced neuroimaging technology, use neuroimaging technology |

| neurotransmitter | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊtrænzˈmɪtə/ | chất dẫn truyền thần kinh | Changes in neurotransmitter systems | dopamine neurotransmitter, release neurotransmitters |

| dopamine | n | /ˈdəʊpəmiːn/ | dopamine (chất dẫn truyền não) | Dopamine shows markedly reduced activity in socially isolated individuals | dopamine levels, dopamine activity, release dopamine |

| reward centers | n | /rɪˈwɔːd ˈsentəz/ | trung tâm phần thưởng (não) | The reward centers of the brain exhibit diminished activation | activate reward centers, stimulate reward centers |

| dysregulated | adj | /dɪsˈreɡjuleɪtɪd/ | rối loạn điều hòa | Serotonin becomes dysregulated during extended isolation | dysregulated system, become dysregulated |

| HPA axis | n | /eɪtʃ piː eɪ ˈæksɪs/ | trục dưới đồi-tuyến yên-thượng thận | The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis becomes hyperactive | activate HPA axis, dysregulated HPA axis |

| cortisol | n | /ˈkɔːtɪsɒl/ | cortisol (hormone căng thẳng) | This results in chronically elevated levels of cortisol | cortisol levels, high cortisol, release cortisol |

| neuroplasticity | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊplæˈstɪsəti/ | tính dẻo thần kinh | Brain structure appears malleable in response, a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity | brain neuroplasticity, demonstrate neuroplasticity |

| gray matter volume | n | /ɡreɪ ˈmætə ˈvɒljuːm/ | thể tích chất xám | Those experiencing persistent isolation show reduced gray matter volume | decreased gray matter volume, measure gray matter volume |

| hippocampus | n | /ˌhɪpəˈkæmpəs/ | hồi hải mã (vùng não) | Sustained cortisol elevation can damage the hippocampus | hippocampus damage, hippocampus function |

| prefrontal cortex | n | /ˌpriːˈfrʌntəl ˈkɔːteks/ | vỏ não trước trán | The prefrontal cortex tends to show particularly pronounced atrophy | prefrontal cortex activity, damage to prefrontal cortex |

| default mode network | n | /dɪˈfɔːlt məʊd ˈnetwɜːk/ | mạng chế độ mặc định | The default mode network shows altered patterns of activity | activate default mode network, DMN connectivity |

| rumination | n | /ˌruːmɪˈneɪʃən/ | sự trầm tư, suy nghĩ lặp đi lặp lại | The DMN becomes hyperactive, leading to excessive rumination | chronic rumination, reduce rumination |

| epigenetics | n | /ˌepɪdʒəˈnetɪks/ | di truyền biểu sinh | Emerging research into epigenetics has revealed changes in gene expression | study epigenetics, epigenetics research |

Sơ đồ từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề cô lập xã hội và tâm lý học

Sơ đồ từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề cô lập xã hội và tâm lý học

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sociocultural frameworks | n | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˈkʌltʃərəl ˈfreɪmwɜːks/ | khung xã hội-văn hóa | They must be contextualized within broader sociocultural frameworks | apply sociocultural frameworks, understand sociocultural frameworks |

| individualistic cultures | n | /ˌɪndɪˌvɪdʒuəˈlɪstɪk ˈkʌltʃəz/ | nền văn hóa cá nhân | Individualistic cultures predominantly found in Western nations | live in individualistic cultures, characteristics of individualistic cultures |

| collectivist cultures | n | /kəˈlektɪvɪst ˈkʌltʃəz/ | nền văn hóa tập thể | Collectivist cultures prioritize group harmony | transition from collectivist cultures, values in collectivist cultures |

| geographic mobility | n | /ˌdʒiːəˈɡræfɪk məʊˈbɪləti/ | tính di động địa lý | Geographic mobility attenuates traditional social support networks | increase geographic mobility, high geographic mobility |

| digital revolution | n | /ˈdɪdʒɪtəl ˌrevəˈluːʃən/ | cuộc cách mạng số | The digital revolution has introduced novel dimensions | impact of digital revolution, during the digital revolution |

| algorithmic curation | n | /ˌælɡəˈrɪðmɪk kjʊəˈreɪʃən/ | quản lý bằng thuật toán | The algorithmic curation of online social experiences | effects of algorithmic curation, algorithmic curation systems |

| structural inequalities | n | /ˈstrʌktʃərəl ˌɪnɪˈkwɒlətiz/ | bất bình đẳng cấu trúc | Structural inequalities create differential exposure to isolation | address structural inequalities, perpetuate structural inequalities |

| socioeconomic marginalization | n | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk ˌmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪˈzeɪʃən/ | sự gạt ra lề kinh tế-xã hội | Socioeconomic marginalization compounds isolation | experience socioeconomic marginalization, overcome socioeconomic marginalization |

| precarious employment | n | /prɪˈkeəriəs ɪmˈplɔɪmənt/ | việc làm bấp bênh | Precarious employment disrupts stable social relationships | rise in precarious employment, effects of precarious employment |

| maladaptive cognitions | n | /ˌmælədˈæptɪv kɒɡˈnɪʃənz/ | nhận thức không thích nghi | Cognitive-behavioral interventions target maladaptive cognitions | identify maladaptive cognitions, change maladaptive cognitions |

| hostile attribution biases | n | /ˈhɒstaɪl ˌætrɪˈbjuːʃən ˈbaɪəsɪz/ | thiên kiến quy kết thù địch | These include hostile attribution biases | demonstrate hostile attribution biases, reduce hostile attribution biases |

| behavioral activation | n | /bɪˈheɪvjərəl ˌæktɪˈveɪʃən/ | kích hoạt hành vi | Interventions combined with behavioral activation components | use behavioral activation, behavioral activation techniques |

| urban planning | n | /ˈɜːbən ˈplænɪŋ/ | quy hoạch đô thị | Urban planning initiatives emphasizing walkable neighborhoods | sustainable urban planning, improve urban planning |

| built environments | n | /bɪlt ɪnˈvaɪrənmənts/ | môi trường xây dựng | Can create built environments conducive to social connection | design built environments, transform built environments |

| medicalization | n | /ˌmedɪkəlaɪˈzeɪʃən/ | y tế hóa | The medicalization of loneliness presents both opportunities and risks | criticize medicalization, process of medicalization |

| multilevel interventions | n | /ˈmʌltilɛvl ˌɪntəˈvenʃənz/ | can thiệp đa cấp độ | Addressing isolation requires multilevel interventions | implement multilevel interventions, design multilevel interventions |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề psychological effects of social isolation không chỉ xuất hiện thường xuyên trong IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh một vấn đề cấp thiết của xã hội hiện đại. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được luyện tập với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần, từ giới thiệu cơ bản về cô lập xã hội, đến các cơ chế thần kinh sinh học phức tạp, và cuối cùng là các khía cạnh xã hội-văn hóa cùng các phương pháp can thiệp.

Bộ 40 câu hỏi đa dạng đã giúp bạn làm quen với tất cả các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến trong IELTS Reading, từ Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, đến Matching Headings và Summary Completion. Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích vị trí thông tin và cách paraphrase sẽ giúp bạn hiểu rõ chiến lược làm bài và tự đánh giá năng lực của mình.

Phần từ vựng được tổng hợp theo từng passage cung cấp những academic words và collocations quan trọng không chỉ cho chủ đề này mà còn áp dụng được cho nhiều bài đọc khác trong IELTS. Hãy dành thời gian học kỹ những từ vựng này và thực hành sử dụng chúng trong ngữ cảnh.

Để đạt kết quả tốt nhất, bạn nên làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật – giới hạn thời gian 60 phút, không tra từ điển, và tự chấm điểm sau đó. Nếu điểm số chưa đạt mục tiêu, đừng nản lòng – hãy phân tích kỹ những câu sai, hiểu tại sao mình chọn sai, và rút ra bài học cho lần làm bài tiếp theo. Sự kiên trì và phương pháp đúng đắn chắc chắn sẽ giúp bạn cải thiện band điểm Reading một cách vững chắc.

[…] toàn có thể đạt được band điểm Reading mục tiêu. Như các nghiên cứu về psychological effects of social isolation cho thấy, việc duy trì động lực và kỷ luật trong học tập là chìa khóa để […]