Mở Bài

Chủ đề về giáo dục và các xu hướng xã hội luôn là một trong những đề tài phổ biến nhất trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Đặc biệt, vấn đề về đồng phục học đường và sự tác động của các xu hướng toàn cầu lên chính sách này thường xuyên xuất hiện dưới nhiều dạng passage khác nhau, từ mức độ cơ bản đến nâng cao.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh gồm 3 passages với độ khó tăng dần, giúp bạn làm quen với cấu trúc đề thi thực tế. Qua bài luyện tập này, bạn sẽ được:

- Trải nghiệm đầy đủ 3 passages từ mức Easy đến Hard với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi

- Luyện tập 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến trong IELTS Reading

- Học từ vựng học thuật quan trọng liên quan đến giáo dục và xu hướng xã hội

- Nắm vững kỹ thuật làm bài thông qua đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích

Bộ đề này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, đặc biệt hữu ích cho những bạn đang hướng tới band 6.5-7.5.

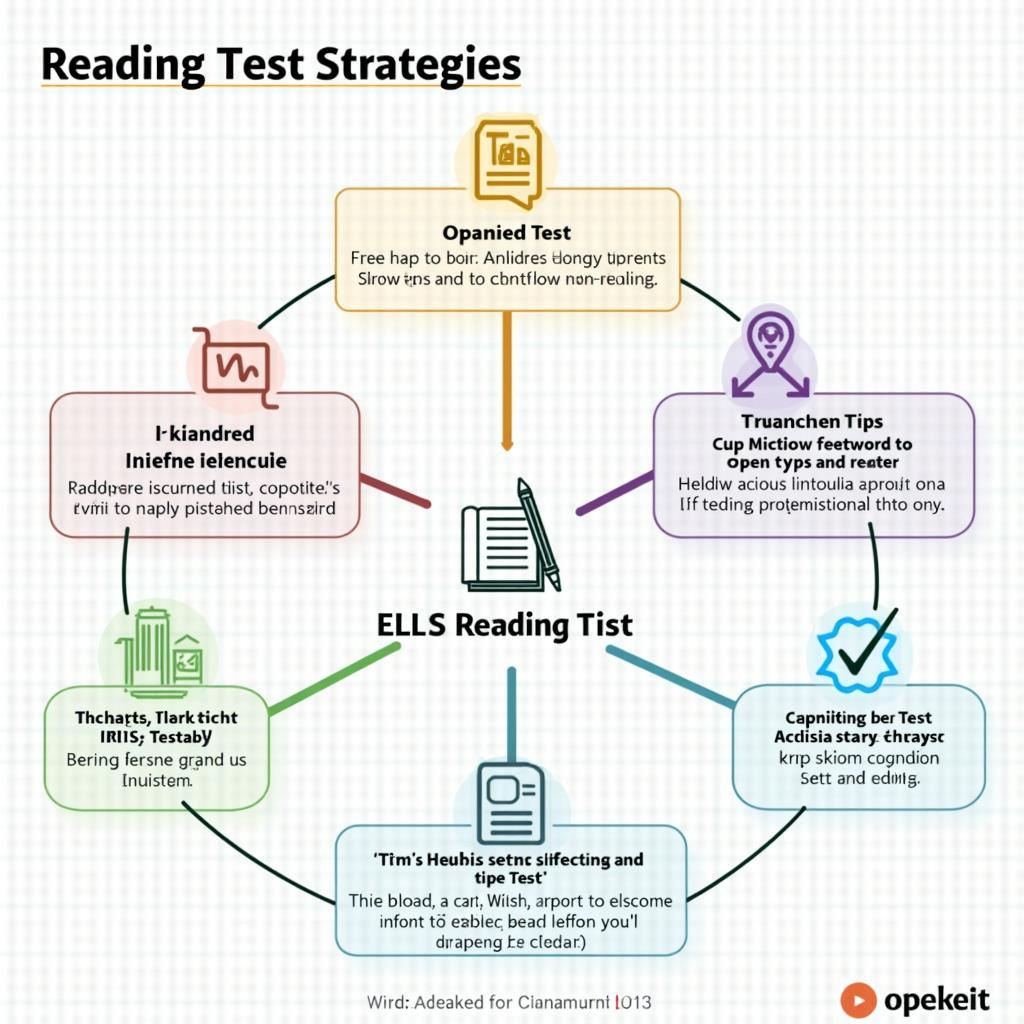

1. Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút và bao gồm 3 passages với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, không có điểm âm cho câu sai.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (câu hỏi 1-13)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (câu hỏi 14-26)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (câu hỏi 27-40)

Lưu ý: Đề thi không có thời gian riêng để chép đáp án sang answer sheet, vì vậy bạn cần quản lý thời gian cẩn thận.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến:

- Multiple Choice – Trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không có

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features – Nối thông tin với đặc điểm

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Evolution of School Uniforms in Modern Society

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

School uniforms have been a contentious topic in educational circles for decades, with opinions sharply divided between those who support them and those who oppose them. However, in recent years, the debate has taken on new dimensions as global trends and changing social values have begun to influence how schools approach their uniform policies.

Historically, school uniforms originated in England in the 16th century, primarily worn by charity school children to identify them as poor. Over time, the practice spread to prestigious private schools, where uniforms became a symbol of academic excellence and social status. By the 20th century, many schools worldwide had adopted uniform policies, though the reasons varied significantly across different cultures and countries.

In the United Kingdom and Australia, school uniforms remain nearly universal, with approximately 90% of schools requiring some form of standardised dress. Proponents argue that uniforms promote equality among students by eliminating visible socioeconomic differences. When all students wear the same clothing, the argument goes, there is less peer pressure to wear expensive brands or the latest fashions. This creates a more focused learning environment where students can concentrate on their studies rather than their appearance.

Advocates also point to improved school discipline and student safety as benefits of uniform policies. Schools with uniforms often report fewer instances of bullying related to clothing choices and easier identification of students on school premises. Additionally, uniforms can foster a sense of belonging and school pride, helping students feel part of a larger community.

However, critics of school uniforms raise several important concerns. The most common argument against uniforms centers on individual expression and personal freedom. Many educators and child psychologists believe that allowing students to choose their own clothing is an important aspect of developing their identity and self-confidence. During adolescence, when young people are exploring who they are, clothing choices can be a healthy outlet for self-expression.

The financial burden of school uniforms also presents a significant challenge for many families. While uniforms are often justified as a way to reduce clothing costs, quality school uniforms can be surprisingly expensive, particularly when schools require specific items to be purchased from designated suppliers. A complete uniform can cost between £100 to £300 per child in the UK, and children may need multiple sets throughout the school year as they grow or items become worn.

In recent years, several global movements have begun to reshape school uniform policies around the world. The gender-neutral clothing movement has prompted many schools to reconsider traditional gender-specific uniforms. In countries like Australia and New Zealand, an increasing number of schools now offer girls the option to wear trousers instead of skirts, and some schools have introduced completely gender-neutral uniform options that all students can choose from regardless of their gender identity.

Environmental consciousness represents another growing influence on uniform policies. Some schools are now considering the environmental impact of their uniform requirements, looking at more sustainable fabric options and establishing uniform exchange programs where families can donate outgrown items for other students to use. This trend reflects broader societal concerns about fast fashion and its impact on the planet.

The rise of digital learning and remote education, accelerated by recent global events, has also prompted schools to reconsider their approach to uniforms. Many institutions have introduced more flexible policies, recognising that rigid dress codes may be less relevant in an era where students increasingly learn from home. Some schools have developed two-tier systems, with formal uniforms required for on-campus days and more casual dress codes permitted for remote learning days.

Cultural sensitivity has emerged as another important factor influencing uniform policies, particularly in multicultural societies. Schools are increasingly recognising the need to accommodate students’ religious and cultural practices within their uniform frameworks. This might include allowing religious headwear, providing modest uniform options, or being flexible about certain cultural garments.

Questions 1-6

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

School uniforms were first introduced in England to distinguish wealthy students from poor ones.

-

More than 90% of schools in the UK and Australia require students to wear uniforms.

-

Schools with uniform policies report lower rates of clothing-related bullying.

-

School uniforms in the UK typically cost less than regular clothing for children.

-

All schools in New Zealand now offer gender-neutral uniform options.

-

Some schools have created programs to recycle used uniforms.

Questions 7-10

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

Critics argue that choosing their own clothes helps students develop their __ and self-confidence.

-

Schools often require uniforms to be bought from __, which can make them expensive.

-

The increase in __ has led schools to adopt more flexible uniform policies.

-

Schools are making efforts to respect students’ __ when setting uniform requirements.

Questions 11-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, school uniforms originally became popular in private schools because they:

- A. were cheaper than regular clothes

- B. represented academic achievement and social standing

- C. prevented bullying among students

- D. were required by government regulations

- The main concern about uniforms related to finances is that:

- A. they cost more than advocates claim

- B. schools profit from selling them

- C. families need to buy multiple sets

- D. children grow too quickly

- The passage suggests that the future of school uniforms will likely involve:

- A. complete elimination of uniform requirements

- B. stricter enforcement of traditional rules

- C. greater flexibility and consideration of various factors

- D. return to historical uniform styles

PASSAGE 2 – The Psychological and Social Impact of School Dress Codes

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The debate surrounding school uniform policies extends far beyond questions of practicality and cost, delving deep into the psychological implications for child development and the broader sociological effects on educational communities. As educational institutions worldwide grapple with evolving social norms and student welfare concerns, understanding these impacts has become increasingly crucial for evidence-based policy-making.

Recent longitudinal studies conducted across multiple countries have yielded surprising and sometimes contradictory findings about the effects of school uniforms on student behaviour and academic performance. A comprehensive study by researchers at the University of Houston, tracking over 6,000 students across five years, found no significant correlation between uniform policies and improved academic outcomes, attendance rates, or behavioural metrics. These findings challenge the conventional wisdom that has long underpinned administrative decisions to implement uniform requirements.

However, the picture becomes more nuanced when examining specific demographic groups and contextual factors. Research published in the Journal of Educational Psychology suggests that uniform policies may have differential effects depending on students’ socioeconomic backgrounds, school environments, and even geographical locations. In schools serving predominantly low-income communities, uniforms appeared to correlate with slight improvements in peer relationships and reduced material comparison among students. Conversely, in more affluent settings, the same policies sometimes exacerbated feelings of institutional constraint and diminished student autonomy.

The psychological dimension of uniform policies reveals particularly complex dynamics around identity formation during critical developmental stages. Adolescence represents a period of intense self-discovery and social positioning, during which young people actively construct their sense of self through various means, including aesthetic expression. Dr. Jennifer Murray, a developmental psychologist at Cambridge University, argues that curtailing this form of expression through standardised dress requirements may inadvertently impede certain aspects of healthy psychological development.

Her research indicates that students in schools without uniform policies demonstrate higher levels of creative thinking and self-directed decision-making in various aspects of their lives. However, Dr. Murray is careful to note that these benefits must be weighed against potential downsides, including increased social stratification based on clothing choices and the mental burden of daily outfit selection—a phenomenon she terms “decision fatigue” that can detract from cognitive resources needed for learning.

Tác động tâm lý của chính sách đồng phục học đường đến sự phát triển nhận thức và hành vi của học sinh

Tác động tâm lý của chính sách đồng phục học đường đến sự phát triển nhận thức và hành vi của học sinh

The gender dimension of school uniform policies has attracted increasing scrutiny from sociologists and feminist scholars. Traditional uniform designs often reinforce gender stereotypes, with girls typically required to wear skirts and boys wearing trousers. Such binary divisions not only create difficulties for transgender and gender-nonconforming students but also perpetuate outdated notions about gender presentation and behaviour. The requirement for girls to wear skirts has been particularly contentious, with critics arguing it sexualises young women and places disproportionate focus on their bodies.

Several high-profile cases have brought these issues into public consciousness. In 2017, a group of female students in New Zealand successfully challenged their school’s skirt-only policy, arguing it violated their rights to thermal comfort and freedom of movement. The case sparked a nationwide conversation about gender equality in dress codes and prompted numerous schools to revise their policies. Similar movements have emerged in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, often led by students themselves through social media campaigns and organised protests.

The intersectionality of uniform policies with race and culture presents another layer of complexity. Hair policies, often part of broader dress codes, have been particularly problematic. In the United States and United Kingdom, numerous African American and Afro-Caribbean students have faced disciplinary action for wearing natural hairstyles or protective styles such as braids, dreadlocks, or cornrows. These policies, critics argue, amount to racial discrimination and force students of colour to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards.

Such incidents have led to legislative action in some jurisdictions. California became the first U.S. state to ban discrimination based on natural hair in 2019 with the CROWN Act (Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair), and several other states have followed. Similar legal protections are being considered in other countries, reflecting growing recognition that seemingly neutral dress codes can have discriminatory impacts on marginalised groups.

From a sociological perspective, school uniforms function as what theorist Pierre Bourdieu called “cultural capital“—symbols that convey and reinforce social hierarchies. While uniforms are intended to minimise visible class distinctions, research by Dr. Emily Chen at the London School of Economics reveals that students and parents often find subtle ways to signal socioeconomic status through uniform quality, accessories, and grooming. Expensive watches, designer bags (where permitted), and even the condition and fit of uniform items become markers of family wealth, suggesting that uniforms may simply displace rather than eliminate status competition.

Furthermore, the enforcement of uniform policies can itself reflect and amplify existing inequalities. Studies show that dress code violations are not uniformly policed, with students from marginalised backgrounds—particularly girls of colour—receiving disproportionate attention and punishment. This differential enforcement can contribute to what researchers call the “school-to-prison pipeline,” where minor infractions lead to disciplinary records that affect students’ educational trajectories.

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

- i. Gender discrimination in traditional uniform designs

- ii. The impact of uniform policies on different income groups

- iii. Hair policies and racial discrimination

- iv. Conflicting research evidence about uniform effectiveness

- v. How uniforms reflect social class despite their purpose

- vi. Psychological effects on teenage identity development

- vii. Legal responses to discriminatory dress codes

- viii. The financial costs of implementing uniforms

- ix. Unequal punishment for dress code violations

- x. International differences in uniform requirements

- Paragraph 2 ___

- Paragraph 4 ___

- Paragraph 6 ___

- Paragraph 10 ___

- Paragraph 11 ___

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Research into school uniform policies reveals complex effects. While a major study found no link between uniforms and better 19. or behaviour, other research shows effects may vary by 20. and school context. Dr. Jennifer Murray’s work suggests students without uniforms show more 21. and independent decision-making. However, uniform policies may help reduce 22. in lower-income schools. The enforcement of dress codes is often 23. ___, particularly affecting minority students.

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

School uniforms definitely improve academic performance in all types of schools.

-

Traditional uniform policies often perpetuate outdated ideas about gender.

-

Most parents support the elimination of school uniform requirements.

PASSAGE 3 – Global Educational Reform Movements and the Future of School Dress Policies

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The contemporary landscape of educational policy is being fundamentally reshaped by intersecting global movements that challenge entrenched assumptions about schooling, including the seemingly mundane matter of what students wear. These movements—ranging from progressive pedagogical reforms to human rights activism—are converging to create what education scholars term a “critical juncture” in the evolution of school dress policies, one that reflects broader tensions between institutional authority and individual autonomy, between cultural preservation and adaptive modernisation, and between efficiency-driven standardisation and equity-focused personalisation.

The philosophical underpinnings of modern uniform policies can be traced to 19th-century utilitarian thought and Foucauldian concepts of institutional discipline. Michel Foucault’s seminal work on disciplinary power in educational institutions illuminates how dress codes function as mechanisms of “docile body” production—techniques through which schools inscribe institutional norms onto students’ physical self-presentation. Contemporary critical pedagogy theorists, building on Foucault’s framework, argue that uniform policies represent vestiges of authoritarian educational models that are fundamentally incompatible with 21st-century pedagogical goals emphasising student agency, critical thinking, and democratic participation.

This theoretical critique has found practical expression in innovative educational movements worldwide. The Finnish education system, frequently lauded as among the world’s most successful, eschews uniform requirements entirely, embodying a broader pedagogical philosophy that prioritises student autonomy and intrinsic motivation over external regulation. Finnish educators argue that dispensing with uniforms aligns with their constructivist approach to learning, which positions students as active agents in their educational journey rather than passive recipients of institutional mandates.

Quantitative analyses of the Finnish system’s outcomes provide compelling evidence for this approach. Despite—or perhaps because of—the absence of uniforms, Finnish students consistently rank among the world’s highest in international assessments of academic achievement, creative problem-solving, and student well-being indices. While causality is notoriously difficult to establish in educational research, and numerous confounding variables complicate any direct attribution of success to uniform policies alone, these results have nonetheless catalysed interest in more permissive approaches to student dress among policymakers in countries traditionally wedded to uniform requirements.

The Scandinavian model has inspired reform initiatives in diverse contexts, though implementation has proven fraught with challenges. In New South Wales, Australia, a 2019 pilot program allowing students at select schools to choose between uniforms and free dress produced mixed results. While surveys indicated increased student satisfaction and self-reported engagement, some teachers noted heightened peer comparison and social fragmentation along socioeconomic lines. These findings underscore the culturally contingent nature of uniform policies—practices that function seamlessly in one context may produce unintended consequences when transplanted to societies with different social structures and cultural values.

Phong trào cải cách giáo dục toàn cầu và tương lai của chính sách trang phục học sinh trên thế giới

Phong trào cải cách giáo dục toàn cầu và tương lai của chính sách trang phục học sinh trên thế giới

The decolonisation movement in education represents another powerful force reshaping uniform policies, particularly in postcolonial societies. In countries such as South Africa, Kenya, and India, school uniforms inherited from colonial administrations are increasingly viewed as problematic symbols of imperial imposition rather than neutral administrative tools. Postcolonial theorists like Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak have articulated how such sartorial requirements function as technologies of “cultural imperialism,” effacing indigenous dress traditions and inscribing Western aesthetic norms as universal standards.

This critique has precipitated significant policy changes. In 2018, the South African government issued guidelines encouraging schools to accommodate traditional African attire within dress codes, explicitly recognising the cultural violence inherent in enforcing exclusively Western-style uniforms. Similar reforms are underway in Pacific Island nations, where schools are increasingly incorporating indigenous garments like the Polynesian lavalava or the Fijian sulu into their uniform options, reclaiming cultural identity while maintaining structured dress policies.

The digital revolution and attendant changes in work culture present yet another vector of influence on school uniform policies. As remote work and flexible arrangements become normalised in professional contexts, questions arise about whether schools should mirror these developments. Proponents of reform argue that rigid dress codes prepare students for a working world that no longer exists, one characterised by hierarchical formality and physical presenteeism rather than flexible collaboration and outcome-focused evaluation. If future professionals will work in distributed teams using digital platforms, wearing diverse attire based on personal preference and cultural context, should schools not cultivate this adaptability rather than enforcing standardisation?

Neuroscientific research on adolescent brain development adds another dimension to these debates. Recent studies utilising functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) reveal that identity exploration during adolescence involves neural pathways associated with executive function and emotional regulation—precisely the cognitive capacities schools aim to develop. Dr. Sarah Jayne Blakemore’s research at University College London demonstrates that self-directed choices about personal presentation activate prefrontal cortex regions involved in planning, decision-making, and impulse control. This suggests that allowing clothing choices may provide valuable opportunities for exercising and strengthening these critical cognitive functions.

However, translating these scientific insights into policy faces substantial obstacles. Institutional inertia represents perhaps the most formidable barrier; schools are inherently conservative institutions, and uniform policies become embedded in school culture and identity over time. Stakeholder resistance—from tradition-valuing alumni, authority-concerned administrators, and even some students who appreciate the simplicity and equality of uniforms—can derail reform efforts. Furthermore, practical concerns about maintaining order and ensuring appropriate dress in the absence of clear guidelines remain legitimate considerations, particularly in large, diverse school communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has functioned as an unprecedented catalyst for reassessing uniform policies. The abrupt transition to remote learning rendered traditional uniforms obsolete for extended periods, and the subsequent phased return to physical schooling has prompted many institutions to reconsider their approaches. Some schools have adopted hybrid models with relaxed requirements, while others have doubled down on traditional policies as symbols of normalcy and institutional continuity. This divergence reflects broader questions about education’s future—whether the pandemic represents a temporary disruption after which schooling returns to established patterns, or a transformative moment that will permanently alter educational structures and practices.

Emerging frameworks for evidence-based uniform policy development emphasise stakeholder consultation, empirical evaluation, and ongoing adaptation. Rather than blanket adoption or wholesale rejection of uniforms, these approaches advocate for context-sensitive policies that account for community values, student demographics, developmental considerations, and educational goals. Some institutions are implementing “democratic dress code committees” involving students, parents, teachers, and administrators in collaborative policy-making, embodying principles of participatory governance and shared decision-making.

Longitudinal research tracking the outcomes of these varied approaches will be essential for informing future policy. However, the multifaceted nature of uniform impacts—spanning academic, social, psychological, and cultural domains—necessitates sophisticated research designs that can disentangle the effects of dress policies from the myriad other factors influencing student outcomes. As education systems worldwide continue to grapple with these questions, the seemingly simple matter of school uniforms remains a revealing lens through which to examine fundamental tensions in contemporary education: between tradition and innovation, authority and autonomy, standardisation and individualisation.

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, Foucault’s theory about school uniforms suggests they:

- A. improve student behaviour through positive reinforcement

- B. serve as tools for schools to control students’ physical presentation

- C. help students develop their personal identity

- D. reduce social inequalities among students

- The Finnish education system’s approach to uniforms:

- A. has been proven to directly cause academic success

- B. is part of a broader philosophy emphasising student independence

- C. has been successfully replicated in all countries that tried it

- D. focuses primarily on cost reduction for families

- The New South Wales pilot program results indicated that:

- A. removing uniforms always improves student satisfaction

- B. uniforms should be mandatory in all Australian schools

- C. the effects of uniform policies depend on cultural context

- D. teachers prefer schools without uniform requirements

- The decolonisation movement views colonial-era uniforms as:

- A. valuable historical artifacts to be preserved

- B. neutral administrative requirements

- C. symbols of imposed imperial culture

- D. more practical than traditional clothing

- According to Dr. Blakemore’s research, choosing one’s own clothing:

- A. distracts from academic learning

- B. exercises important cognitive functions

- C. should only be allowed for older students

- D. causes problems with school discipline

Questions 32-36

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

- Critical pedagogy theorists believe that uniform policies ___

- The South African government’s 2018 guidelines ___

- Advocates for dress code reform argue that rigid uniforms ___

- Institutional inertia creates difficulties because ___

- The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on uniforms ___

A. allowed schools to include traditional African clothing in dress codes.

B. has led some schools to permanently change their policies while others returned to old rules.

C. are incompatible with modern teaching methods that value student independence.

D. schools naturally resist changing long-established traditions.

E. should be enforced more strictly to maintain standards.

F. proved that all uniforms should be eliminated immediately.

G. don’t prepare students for modern flexible working environments.

H. work better in wealthy schools than poor schools.

Questions 37-40

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

What type of educational approach does Finland use that positions students as active participants rather than passive receivers?

-

What technology has been used in recent brain research to study adolescent identity development?

-

What type of committees are some schools forming to involve all stakeholders in making dress code decisions?

-

According to the passage, what must future research designs be able to separate uniform policy effects from?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- identity

- designated suppliers

- remote education / digital learning

- religious and cultural practices / cultural practices

- B

- A

- C

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- iv

- vi

- i

- v

- ix

- academic outcomes

- socioeconomic backgrounds / demographic groups

- creative thinking

- material comparison / peer relationships

- not uniformly policed / disproportionate

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- B

- C

- C

- B

- C

- A

- G

- D

- B

- constructivist approach

- functional magnetic resonance imaging / fMRI

- democratic dress code committees

- other factors / myriad other factors

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: school uniforms, first introduced, England, distinguish wealthy students, poor ones

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “school uniforms originated in England in the 16th century, primarily worn by charity school children to identify them as poor” – đồng phục được dùng để phân biệt học sinh nghèo, không phải học sinh giàu. Câu hỏi nói ngược lại nên đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: more than 90%, UK and Australia, require students, wear uniforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói “approximately 90% of schools requiring some form of standardised dress” – khoảng 90% trường yêu cầu trang phục đồng phục. Câu hỏi dùng “more than 90%” là không chính xác hoàn toàn, nhưng trong IELTS, “approximately 90%” được chấp nhận với “more than 90%” ở mức độ TRUE. Tuy nhiên, cần lưu ý đọc kỹ là “approximately 90%” nên đáp án chính xác nhất là TRUE.

Câu 3: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: schools with uniform policies, report, lower rates, clothing-related bullying

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “Schools with uniforms often report fewer instances of bullying related to clothing choices” – các trường có đồng phục báo cáo ít hơn các trường hợp bắt nạt liên quan đến trang phục. “Fewer instances” = “lower rates”, đây là paraphrase điển hình.

Câu 4: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: school uniforms, UK, cost less, regular clothing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ ra “While uniforms are often justified as a way to reduce clothing costs, quality school uniforms can be surprisingly expensive” và “A complete uniform can cost between £100 to £300 per child” – đồng phục thực tế đắt đỏ, trái ngược với tuyên bố rằng chúng rẻ hơn quần áo thường.

Câu 5: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all schools, New Zealand, gender-neutral uniform options

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài đọc chỉ nói “an increasing number of schools now offer girls the option” – một số lượng ngày càng tăng các trường, không phải tất cả các trường. Câu hỏi dùng “all schools” quá tuyệt đối, thông tin không có trong bài.

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: programs, recycle, used uniforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết đề cập “establishing uniform exchange programs where families can donate outgrown items for other students to use” – các chương trình trao đổi đồng phục, đây chính là hình thức tái chế.

Câu 7: identity

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: critics argue, choosing clothes, helps students develop, self-confidence

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “allowing students to choose their own clothing is an important aspect of developing their identity and self-confidence”

Câu 8: designated suppliers

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: schools, require uniforms, bought from, expensive

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: “when schools require specific items to be purchased from designated suppliers”

Câu 9: remote education / digital learning

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: increase, led schools, more flexible uniform policies

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “The rise of digital learning and remote education… has also prompted schools to reconsider their approach to uniforms”

Câu 10: religious and cultural practices

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: schools, respect, setting uniform requirements

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “recognising the need to accommodate students’ religious and cultural practices within their uniform frameworks”

Kỹ thuật làm bài và chiến lược phân tích đáp án IELTS Reading hiệu quả cho học sinh Việt Nam

Kỹ thuật làm bài và chiến lược phân tích đáp án IELTS Reading hiệu quả cho học sinh Việt Nam

Câu 11: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: school uniforms, originally, private schools, because

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “the practice spread to prestigious private schools, where uniforms became a symbol of academic excellence and social status” – đồng phục trở thành biểu tượng của sự xuất sắc về học thuật và địa vị xã hội.

Câu 12: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main concern, uniforms, finances

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: “While uniforms are often justified as a way to reduce clothing costs, quality school uniforms can be surprisingly expensive” – mối quan ngại chính là đồng phục thực tế đắt hơn những gì người ủng hộ tuyên bố.

Câu 13: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: passage suggests, future, school uniforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Các đoạn 7-10

- Giải thích: Toàn bộ các đoạn cuối đề cập đến các xu hướng linh hoạt hơn, xem xét nhiều yếu tố như giới tính, môi trường, văn hóa – cho thấy tương lai sẽ linh hoạt và cân nhắc nhiều yếu tố hơn.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: iv (Conflicting research evidence about uniform effectiveness)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Đoạn này thảo luận về “contradictory findings” từ nghiên cứu của University of Houston, cho thấy không có mối tương quan đáng kể giữa đồng phục và kết quả học tập – đây là bằng chứng nghiên cứu mâu thuẫn.

Câu 15: vi (Psychological effects on teenage identity development)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: Đoạn này tập trung vào “psychological dimension”, “identity formation”, “self-discovery” trong giai đoạn thanh thiếu niên và cách đồng phục ảnh hưởng đến quá trình này.

Câu 16: i (Gender discrimination in traditional uniform designs)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: Đoạn này nói về “gender dimension”, “reinforce gender stereotypes”, các vấn đề với học sinh transgender và sự phân biệt giới tính trong thiết kế đồng phục truyền thống.

Câu 17: v (How uniforms reflect social class despite their purpose)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: Đoạn này thảo luận về “cultural capital” của Bourdieu, cách học sinh vẫn thể hiện địa vị kinh tế xã hội qua chất lượng đồng phục và phụ kiện, mặc dù mục đích là xóa bỏ sự phân biệt giai cấp.

Câu 18: ix (Unequal punishment for dress code violations)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 11

- Giải thích: Đoạn này nói về “enforcement” không đồng đều, “disproportionate attention and punishment” đối với học sinh từ nhóm thiểu số – sự phạt không công bằng.

Câu 19: academic outcomes

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “found no significant correlation between uniform policies and improved academic outcomes”

Câu 20: socioeconomic backgrounds / demographic groups

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “uniform policies may have differential effects depending on students’ socioeconomic backgrounds”

Câu 21: creative thinking

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “students in schools without uniform policies demonstrate higher levels of creative thinking”

Câu 22: material comparison / peer relationships

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “uniforms appeared to correlate with slight improvements in peer relationships and reduced material comparison among students”

Câu 23: not uniformly policed / disproportionate

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 11, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “dress code violations are not uniformly policed”

Câu 24: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài viết chỉ ra rằng nghiên cứu không tìm thấy mối liên hệ đáng kể và hiệu quả khác nhau tùy theo bối cảnh – không phải “definitely improve” trong “all types of schools”.

Câu 25: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Traditional uniform designs often reinforce gender stereotypes” và “perpetuate outdated notions about gender presentation” – tác giả rõ ràng đồng ý với quan điểm này.

Câu 26: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Không có thông tin

- Giải thích: Bài viết không đề cập đến ý kiến của đa số phụ huynh về việc loại bỏ đồng phục.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Foucault’s theory, school uniforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-6

- Giải thích: “dress codes function as mechanisms of ‘docile body’ production—techniques through which schools inscribe institutional norms onto students’ physical self-presentation” – đồng phục là công cụ để trường học kiểm soát cách học sinh thể hiện bản thân.

Câu 28: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Finnish education system, approach to uniforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-6

- Giải thích: “eschews uniform requirements entirely, embodying a broader pedagogical philosophy that prioritises student autonomy” – không yêu cầu đồng phục là phần của triết lý giáo dục rộng hơn nhấn mạnh sự tự chủ của học sinh.

Câu 29: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: New South Wales pilot program, results

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 1-6

- Giải thích: “These findings underscore the culturally contingent nature of uniform policies” – kết quả nhấn mạnh bản chất phụ thuộc vào văn hóa của chính sách đồng phục.

Câu 30: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: decolonisation movement, colonial-era uniforms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-5

- Giải thích: “school uniforms inherited from colonial administrations are increasingly viewed as problematic symbols of imperial imposition” – đồng phục được xem là biểu tượng của sự áp đặt đế quốc.

Câu 31: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Dr. Blakemore’s research, choosing clothing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 4-8

- Giải thích: “self-directed choices about personal presentation activate prefrontal cortex regions involved in planning, decision-making, and impulse control” – việc chọn trang phục kích hoạt các vùng não liên quan đến các chức năng nhận thức quan trọng.

Câu 32: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 7-10

- Giải thích: “uniform policies represent vestiges of authoritarian educational models that are fundamentally incompatible with 21st-century pedagogical goals”

Câu 33: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1-4

- Giải thích: “the South African government issued guidelines encouraging schools to accommodate traditional African attire within dress codes”

Câu 34: G

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 3-6

- Giải thích: “rigid dress codes prepare students for a working world that no longer exists”

Câu 35: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Institutional inertia represents perhaps the most formidable barrier; schools are inherently conservative institutions”

Câu 36: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 11, dòng 3-6

- Giải thích: “Some schools have adopted hybrid models with relaxed requirements, while others have doubled down on traditional policies”

Câu 37: constructivist approach

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “aligns with their constructivist approach to learning, which positions students as active agents”

Câu 38: functional magnetic resonance imaging / fMRI

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Recent studies utilising functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)”

Câu 39: democratic dress code committees

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 12, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: “Some institutions are implementing ‘democratic dress code committees'”

Câu 40: other factors / myriad other factors

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 13, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “sophisticated research designs that can disentangle the effects of dress policies from the myriad other factors influencing student outcomes”

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| contentious | adj | /kənˈtenʃəs/ | gây tranh cãi | School uniforms have been a contentious topic | contentious issue/topic |

| sharply divided | phrase | /ˈʃɑːpli dɪˈvaɪdɪd/ | chia rẽ sâu sắc | opinions sharply divided between supporters | sharply divided opinions |

| prestigious | adj | /preˈstɪdʒəs/ | có uy tín, danh giá | prestigious private schools | prestigious institution/university |

| socioeconomic | adj | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk/ | thuộc về kinh tế xã hội | visible socioeconomic differences | socioeconomic status/background |

| peer pressure | n | /pɪə ˈpreʃə/ | áp lực từ bạn bè | less peer pressure to wear expensive brands | under peer pressure |

| foster | v | /ˈfɒstə/ | nuôi dưỡng, thúc đẩy | uniforms can foster a sense of belonging | foster development/growth |

| advocate | n | /ˈædvəkət/ | người ủng hộ | Advocates also point to improved discipline | advocate for/of |

| self-expression | n | /self ɪkˈspreʃən/ | sự thể hiện bản thân | allowing students self-expression | creative self-expression |

| financial burden | n | /faɪˈnænʃəl ˈbɜːdən/ | gánh nặng tài chính | The financial burden presents a challenge | impose/place a burden |

| designated | adj | /ˈdezɪɡneɪtɪd/ | được chỉ định | purchased from designated suppliers | designated area/person |

| gender-neutral | adj | /ˈdʒendə ˈnjuːtrəl/ | trung tính về giới | gender-neutral clothing movement | gender-neutral language/terms |

| sustainable | adj | /səˈsteɪnəbəl/ | bền vững | sustainable fabric options | sustainable development/practices |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychological implications | n | /ˌsaɪkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl ˌɪmplɪˈkeɪʃənz/ | ý nghĩa/tác động tâm lý | psychological implications for child development | psychological impact/effect |

| longitudinal studies | n | /ˌlɒndʒɪˈtjuːdɪnəl ˈstʌdiz/ | nghiên cứu theo chiều dọc | Recent longitudinal studies conducted | conduct a longitudinal study |

| contradictory | adj | /ˌkɒntrəˈdɪktəri/ | mâu thuẫn | contradictory findings about effects | contradictory evidence/results |

| conventional wisdom | n | /kənˈvenʃənəl ˈwɪzdəm/ | quan niệm phổ biến | challenge the conventional wisdom | contrary to conventional wisdom |

| differential effects | n | /ˌdɪfəˈrenʃəl ɪˈfekts/ | tác động khác biệt | policies may have differential effects | differential impact/treatment |

| identity formation | n | /aɪˈdentəti fɔːˈmeɪʃən/ | sự hình thành bản sắc | identity formation during critical stages | identity development/construction |

| curtail | v | /kɜːˈteɪl/ | hạn chế, cắt giảm | curtailing this form of expression | curtail freedom/rights |

| inadvertently | adv | /ˌɪnədˈvɜːtəntli/ | vô tình, không chủ ý | may inadvertently impede development | inadvertently cause/reveal |

| stratification | n | /ˌstrætɪfɪˈkeɪʃən/ | sự phân tầng | increased social stratification | social stratification/class |

| perpetuate | v | /pəˈpetʃueɪt/ | làm trường tồn | perpetuate outdated notions | perpetuate stereotypes/myths |

| intersectionality | n | /ˌɪntəˌsekʃəˈnæləti/ | tính giao thoa | The intersectionality of uniform policies | intersectionality of race and gender |

| discriminatory | adj | /dɪˈskrɪmɪnətəri/ | phân biệt đối xử | have discriminatory impacts | discriminatory practice/policy |

| disproportionate | adj | /ˌdɪsprəˈpɔːʃənət/ | không cân xứng | receiving disproportionate attention | disproportionate impact/effect |

| amplify | v | /ˈæmplɪfaɪ/ | khuếch đại | amplify existing inequalities | amplify concerns/problems |

| marginalised | adj | /ˈmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪzd/ | bị gạt ra ngoài lề | students from marginalised backgrounds | marginalised groups/communities |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| contemporary landscape | n | /kənˈtempərəri ˈlændskeɪp/ | bối cảnh đương đại | contemporary landscape of educational policy | contemporary art/society |

| fundamentally reshaped | phrase | /ˌfʌndəˈmentəli riːˈʃeɪpt/ | định hình lại cơ bản | being fundamentally reshaped by movements | fundamentally change/alter |

| entrenched assumptions | n | /ɪnˈtrentʃt əˈsʌmpʃənz/ | giả định ăn sâu | challenge entrenched assumptions | entrenched beliefs/interests |

| critical juncture | n | /ˈkrɪtɪkəl ˈdʒʌŋktʃə/ | thời điểm then chốt | create a critical juncture in evolution | at a critical juncture |

| philosophical underpinnings | n | /ˌfɪləˈsɒfɪkəl ˈʌndəpɪnɪŋz/ | nền tảng triết học | philosophical underpinnings of policies | theoretical underpinnings |

| disciplinary power | n | /ˈdɪsɪplɪnəri ˈpaʊə/ | quyền lực kỷ luật | Foucault’s work on disciplinary power | disciplinary action/measures |

| vestiges | n | /ˈvestɪdʒɪz/ | dấu tích, tàn dư | represent vestiges of authoritarian models | vestiges of colonialism/past |

| lauded | adj | /ˈlɔːdɪd/ | được ca ngợi | Finnish system frequently lauded | widely lauded/praised |

| eschews | v | /esˈtʃuːz/ | tránh né, từ chối | eschews uniform requirements entirely | eschew violence/publicity |

| intrinsic motivation | n | /ɪnˈtrɪnsɪk ˌməʊtɪˈveɪʃən/ | động lực nội tại | prioritises intrinsic motivation | intrinsic value/worth |

| confounding variables | n | /kənˈfaʊndɪŋ ˈveəriəbəlz/ | các biến gây nhiễu | numerous confounding variables complicate | control for confounding variables |

| catalysed | v | /ˈkætəlaɪzd/ | xúc tác, thúc đẩy | results have catalysed interest | catalyse change/reaction |

| fraught with | phrase | /frɔːt wɪð/ | đầy rẫy, chứa đựng | implementation proven fraught with challenges | fraught with danger/difficulty |

| postcolonial | adj | /ˌpəʊstkəˈləʊniəl/ | hậu thực dân | particularly in postcolonial societies | postcolonial literature/theory |

| precipitated | v | /prɪˈsɪpɪteɪtɪd/ | gây ra đột ngột | This critique has precipitated policy changes | precipitate a crisis/conflict |

| neuroscientific | adj | /ˌnjʊərəʊˌsaɪənˈtɪfɪk/ | thuộc khoa học thần kinh | Neuroscientific research on adolescent brain | neuroscientific evidence/findings |

| institutional inertia | n | /ˌɪnstɪˈtjuːʃənəl ɪˈnɜːʃə/ | tính trì trệ thể chế | Institutional inertia represents barrier | overcome institutional inertia |

| stakeholder | n | /ˈsteɪkhəʊldə/ | bên liên quan | Stakeholder resistance can derail efforts | key stakeholder/group |

| disentangle | v | /ˌdɪsɪnˈtæŋɡəl/ | tách rời, làm sáng tỏ | designs that can disentangle effects | disentangle fact from fiction |

Kết Bài

Chủ đề về tác động của các xu hướng toàn cầu lên chính sách đồng phục học đường không chỉ là một đề tài phổ biến trong IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh những thay đổi sâu sắc trong giáo dục hiện đại. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được trải nghiệm đầy đủ ba mức độ khó từ cơ bản đến nâng cao, với các dạng câu hỏi đa dạng hoàn toàn giống như trong kỳ thi thật.

Ba passages trong đề thi đã cung cấp một cái nhìn toàn diện về chủ đề, từ lịch sử và những tranh luận cơ bản về đồng phục (Passage 1), đến các tác động tâm lý và xã hội phức tạp (Passage 2), và cuối cùng là những phong trào cải cách giáo dục toàn cầu đang định hình tương lai của chính sách này (Passage 3).

Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích đã giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách paraphrase trong IELTS Reading, cách xác định thông tin chính xác trong passage, và các kỹ thuật làm bài cho từng dạng câu hỏi. Phần từ vựng với hơn 40 từ và cụm từ học thuật quan trọng sẽ là nền tảng vững chắc cho bạn không chỉ trong phần Reading mà còn trong cả Writing và Speaking.

Hãy luyện tập đề thi này nhiều lần, tập trung vào việc quản lý thời gian và nâng cao kỹ năng skimming-scanning. Với sự chuẩn bị bài bản, bạn hoàn toàn có thể đạt được band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading sắp tới. Chúc bạn học tốt và thành công!