Mở bài

Chủ đề “The Rise Of Green Energy Technologies” (Sự phát triển của công nghệ năng lượng xanh) đã và đang trở thành một trong những đề tài phổ biến nhất trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading trong những năm gần đây. Với xu hướng toàn cầu hóa và sự quan tâm ngày càng tăng đối với biến đổi khí hậu, các bài đọc về năng lượng tái tạo, công nghệ bền vững và giải pháp môi trường thường xuyên xuất hiện trong các đề thi IELTS thực tế.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với ba passages được thiết kế theo đúng format chuẩn quốc tế, bao gồm độ khó tăng dần từ Easy đến Hard. Bạn sẽ được thực hành với 40 câu hỏi đa dạng giống như thi thật, kèm theo đáp án chi tiết và giải thích cụ thể giúp bạn hiểu rõ phương pháp làm bài. Ngoài ra, bạn còn được trang bị vốn từ vựng quan trọng và các kỹ thuật làm bài hiệu quả.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với cấu trúc đề thi, rèn luyện kỹ năng đọc hiểu và quản lý thời gian một cách khoa học nhất.

Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test là một phần thi quan trọng trong kỳ thi IELTS Academic, đánh giá khả năng đọc hiểu tiếng Anh học thuật của thí sinh. Bài thi kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, và tổng điểm sẽ được quy đổi thành band score từ 1-9.

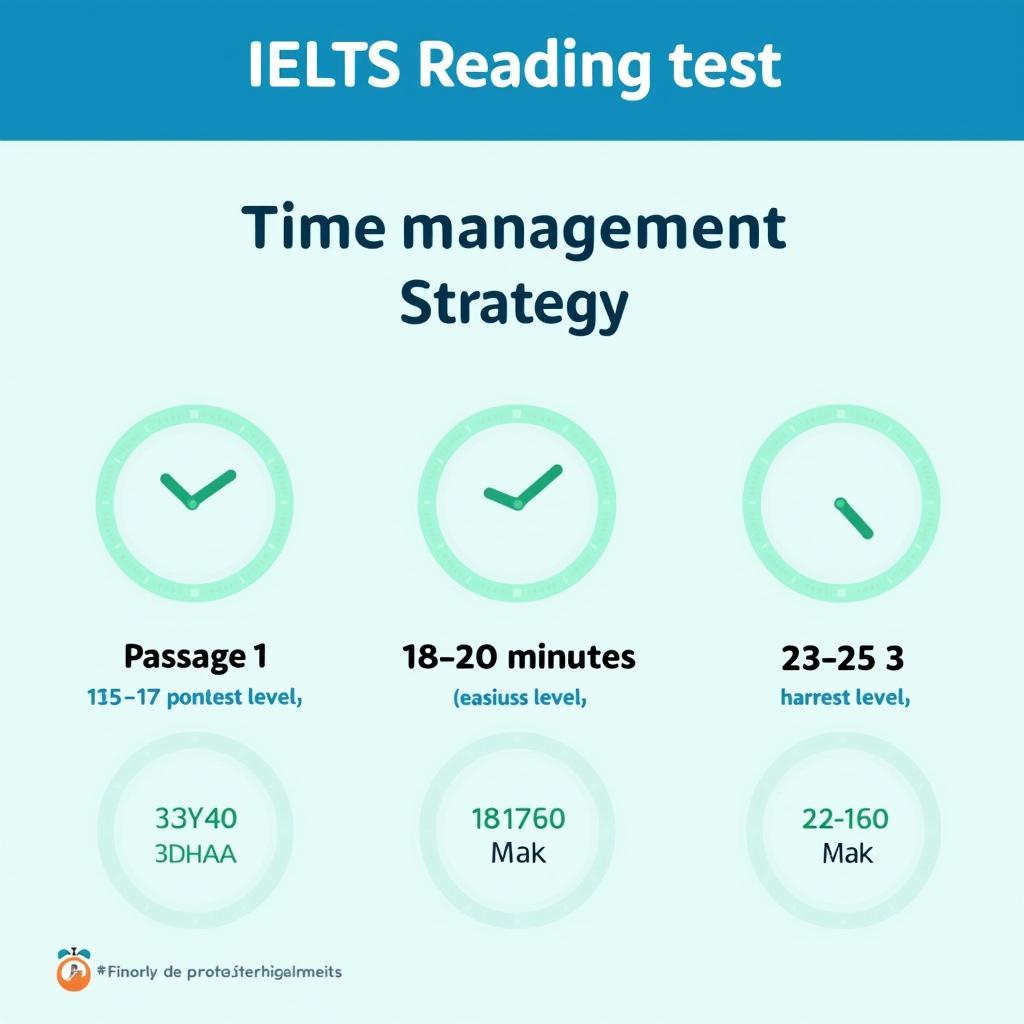

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1 (Easy): 15-17 phút

- Passage 2 (Medium): 18-20 phút

- Passage 3 (Hard): 23-25 phút

- Thời gian chuyển đáp án: 2-3 phút

Lưu ý rằng không có thời gian bổ sung để chuyển đáp án vào answer sheet, do đó bạn cần quản lý thời gian thật tốt ngay từ đầu.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm nhiều lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không được đề cập

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn tương ứng

- Matching Headings – Chọn tiêu đề phù hợp cho các đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành đoạn tóm tắt

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

Mỗi dạng câu hỏi yêu cầu một kỹ năng đọc hiểu khác nhau, từ scanning (đọc lướt tìm thông tin cụ thể) đến skimming (đọc lướt nắm ý chính) và reading for detail (đọc kỹ để hiểu chi tiết).

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Solar Revolution: From Luxury to Necessity

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The transformation of solar energy from an expensive alternative to a mainstream power source represents one of the most remarkable success stories in modern technology. Just two decades ago, solar panels were considered a luxury item, primarily used by environmentally conscious homeowners willing to pay premium prices for clean energy. Today, the landscape has changed dramatically, with solar power becoming the fastest-growing energy source worldwide.

The journey began in the 1950s when scientists at Bell Laboratories created the first practical photovoltaic cell, capable of converting sunlight directly into electricity. However, early solar panels were prohibitively expensive, costing approximately $300 per watt of generating capacity. This made them economically unviable for most applications except in remote locations where connecting to the electricity grid was impossible or impractical, such as communication satellites and isolated research stations.

The turning point came in the early 2000s when several factors converged to drive down costs and improve efficiency. Government subsidies and incentives in countries like Germany, Japan, and the United States encouraged both manufacturers and consumers to invest in solar technology. These financial support mechanisms created a stable market that allowed companies to invest in research and development, leading to significant technological improvements. Manufacturing processes became more streamlined, and economies of scale began to take effect as production volumes increased.

China’s entry into the solar panel manufacturing market in the mid-2000s proved to be a game-changer. Chinese manufacturers invested heavily in production capacity, benefiting from lower labour costs and government support. This resulted in a dramatic reduction in panel prices – from around $76 per watt in 1977 to less than $0.30 per watt by 2020. Such a precipitous decline made solar energy cost-competitive with traditional fossil fuels in many regions, particularly in sunny climates where solar irradiation levels are high.

Công nghệ pin mặt trời hiện đại với hiệu suất cao và giá thành hợp lý

Công nghệ pin mặt trời hiện đại với hiệu suất cao và giá thành hợp lý

Technological innovations have also played a crucial role in solar energy’s ascent. Early solar panels had conversion efficiencies of only 6%, meaning they could convert just 6% of the sunlight they received into usable electricity. Modern commercial panels now routinely achieve efficiencies of 20-22%, while laboratory prototypes have reached over 40% efficiency. Improvements in silicon purification, anti-reflective coatings, and cell architecture have all contributed to these gains.

The integration of solar power into existing electricity grids presented another challenge that has been gradually overcome. Solar energy is intermittent – it only generates power when the sun is shining. This variability initially made it difficult for grid operators to maintain a stable power supply. However, advances in battery storage technology, particularly lithium-ion batteries, have addressed this issue. Modern energy storage systems can store excess solar power generated during the day for use at night or during cloudy periods, making solar energy a more reliable baseload power source.

The environmental benefits of solar energy extend beyond simply reducing carbon emissions from electricity generation. Unlike fossil fuel power plants, solar installations require no water for cooling, making them ideal for arid regions where water is scarce. They also produce no air pollution during operation and have a relatively small physical footprint compared to coal mines or oil fields. While the manufacturing process does have environmental impacts, studies show that solar panels typically generate net positive energy within 1-4 years of operation, depending on location and technology type.

The economic impact of the solar revolution has been profound. The industry now employs over 4 million people globally, with jobs ranging from panel manufacturing and installation to system design and maintenance. In many developing countries, solar power has enabled electrification of remote communities that were never connected to centralized grids, improving quality of life and enabling economic development. Small-scale solar systems power everything from water pumps for agriculture to mobile phone charging stations in rural areas.

Looking ahead, experts predict that solar energy will continue its rapid growth trajectory. The International Energy Agency forecasts that solar could become the world’s largest source of electricity by 2050. Emerging technologies such as perovskite solar cells, which promise even higher efficiencies at lower costs, and bifacial panels that can capture sunlight from both sides, are currently in development. As costs continue to fall and efficiency improves, solar energy is increasingly becoming not just an environmentally conscious choice, but the economically rational one.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, solar panels in the 1950s were primarily used in

A. residential homes

B. commercial buildings

C. remote locations

D. industrial facilities -

What was the approximate cost per watt of solar panels in 1977?

A. $0.30

B. $76

C. $300

D. $400 -

The passage suggests that China’s entry into solar manufacturing was significant because

A. it improved panel efficiency dramatically

B. it created new battery storage technology

C. it reduced production costs substantially

D. it developed new types of solar cells -

Modern commercial solar panels typically have conversion efficiencies of

A. 6%

B. 10-12%

C. 20-22%

D. over 40% -

According to the passage, solar panels generate net positive energy within

A. 1-4 months

B. 1-4 years

C. 5-10 years

D. 10-20 years

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage? Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- Bell Laboratories created the first solar panel in the 1950s.

- Germany was the first country to provide subsidies for solar energy.

- Solar energy produces air pollution during operation.

- The solar industry employs more than 4 million people worldwide.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

The integration of solar power was challenging because solar energy is __ and only works when the sun shines.

-

Modern __ can store excess solar power for use during cloudy periods or at night.

-

Solar installations require no __ for cooling, making them suitable for dry regions.

-

The International Energy Agency predicts that solar could become the world’s largest __ by 2050.

PASSAGE 2 – Wind Power: Harnessing Nature’s Invisible Force

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

Wind energy has emerged as a cornerstone of the global transition to renewable power, with wind turbines now dotting landscapes and offshore installations from the North Sea to the coast of Taiwan. Unlike solar power, which has ancient applications primarily in heating and lighting, wind power for electricity generation is a relatively recent development that has undergone exponential growth since the 1980s. The technology’s evolution from small experimental turbines to today’s massive offshore installations illustrates both human ingenuity and the scalable potential of renewable energy.

The fundamental principle behind wind power is deceptively simple: moving air possesses kinetic energy that can be captured and converted into electricity. Modern horizontal-axis wind turbines – the most common type – consist of three main components: the rotor blades that capture wind energy, the nacelle housing the generator and gearbox, and the tower supporting the structure at heights where wind speeds are strongest and most consistent. As wind passes over the aerodynamically designed blades, it creates lift similar to an aircraft wing, causing the rotor to spin. This rotational energy is then transmitted through a drivetrain to a generator that produces electricity.

The efficiency of wind energy conversion has improved dramatically through aerodynamic refinements and materials science advances. Early turbines in the 1980s had rotor diameters of approximately 15 meters and could generate around 50 kilowatts of power. Today’s offshore wind turbines feature rotors spanning over 220 meters – larger than the wingspan of an Airbus A380 – and can produce 15 megawatts or more, enough to power approximately 15,000 homes. This three-hundredfold increase in capacity represents one of the most impressive scaling achievements in engineering history.

Offshore wind farms have become particularly attractive for several reasons. Wind speeds over water are typically higher and more consistent than on land, resulting in greater energy yields. Offshore locations also avoid many of the land-use conflicts associated with onshore installations, such as noise complaints from nearby residents or concerns about visual impact on landscapes. However, offshore development presents its own challenges, including harsher operating conditions, more complex installation procedures, and higher maintenance costs due to the corrosive marine environment.

Trang trại điện gió ngoài khơi hiện đại với tuabin công suất lớn trên biển

Trang trại điện gió ngoài khơi hiện đại với tuabin công suất lớn trên biển

The intermittency of wind power – the fact that wind doesn’t blow constantly or predictably – has historically been cited as a major limitation. However, several technological and operational strategies have mitigated this concern. Geographic diversification of wind farms means that calm conditions in one location are often offset by stronger winds elsewhere. Advanced weather forecasting models now enable grid operators to predict wind generation with reasonable accuracy 24-48 hours in advance, allowing them to adjust other power sources accordingly. Additionally, as with solar power, battery storage systems and other energy storage technologies are increasingly being paired with wind farms to smooth output and provide power during calm periods.

Grid integration remains a complex challenge, particularly in regions with high penetration rates of wind power. Denmark, for example, sometimes generates more than 100% of its electricity needs from wind, requiring sophisticated systems to manage excess generation. This has led to innovations in demand-response programs, where energy-intensive industries adjust their consumption based on electricity availability, and interconnection networks that allow surplus power to be exported to neighbouring countries. The development of smart grid technologies has been crucial in enabling these flexible systems.

The economic case for wind power has strengthened considerably. The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) – a measure that includes all lifetime costs divided by total energy production – for onshore wind has fallen by approximately 70% since 2009. In many locations, new wind farms can now generate electricity more cheaply than coal or natural gas power plants, even without subsidies. This cost competitiveness, similar to how clean energy is driving job creation across multiple sectors, has attracted significant private investment and accelerated deployment.

Environmental considerations surrounding wind power are nuanced. While wind turbines produce no greenhouse gas emissions during operation and have a relatively small land footprint – the base of a large turbine occupies less than half an acre – they do have environmental impacts. Bird and bat mortality from collisions with turbine blades has been documented, though studies suggest the numbers are relatively small compared to deaths from other human activities like buildings and vehicles. Careful site selection and operational modifications, such as temporarily shutting down turbines during migration periods, can further reduce wildlife impacts.

The manufacturing and installation of wind turbines require significant amounts of materials, including steel, concrete, fiberglass, and rare earth elements used in generators. However, life cycle assessments indicate that wind turbines typically recoup the energy invested in their production within 6-12 months of operation, spending the remaining 20-25 years of their operational life generating net positive energy. Recyclability is an emerging concern as early-generation turbines reach end-of-life, particularly for composite blade materials that are challenging to recycle with current technologies.

Looking forward, several innovations promise to enhance wind power’s contribution to decarbonization efforts. Floating offshore platforms could unlock wind resources in deep waters previously inaccessible to conventional fixed-bottom turbines. Airborne wind energy systems, which use kites or tethered aircraft to capture stronger, more consistent winds at higher altitudes, are in development. Meanwhile, digitalization and artificial intelligence are optimizing turbine performance through predictive maintenance and adaptive control systems that adjust blade pitch and yaw angle in real-time to maximize energy capture.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer? Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Wind power for electricity generation has a longer history than solar power applications.

- Modern offshore wind turbines can power approximately 15,000 homes each.

- Offshore wind farms are more expensive to maintain than onshore installations.

- Denmark has completely eliminated the use of fossil fuels for electricity generation.

- Wind turbines cause more bird deaths than collisions with buildings.

Questions 19-22: Matching Headings

The passage has ten paragraphs. Choose the correct heading for paragraphs 3, 5, 7, and 9 from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. Environmental impacts and mitigation strategies

ii. The basic mechanics of wind energy conversion

iii. Dramatic improvements in turbine size and capacity

iv. Addressing the challenge of variable wind conditions

v. The future of offshore wind technology

vi. Economic advantages driving wind power adoption

vii. Manufacturing challenges and sustainability concerns

viii. Grid management in high wind-penetration regions

- Paragraph 3: __

- Paragraph 5: __

- Paragraph 7: __

- Paragraph 9: __

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Modern wind turbines work by using (23) __ that capture the kinetic energy of moving air. The blades create (24) __ similar to an aircraft wing, causing rotation that drives a generator. Today’s offshore turbines have rotors larger than (25) __ and can generate 15 megawatts of power. Although wind is variable, (26) __ allows grid operators to predict generation patterns and manage power supply effectively.

PASSAGE 3 – The Geopolitical Implications of the Green Energy Transition

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The paradigm shift from fossil fuel dependency to renewable energy systems represents far more than a technological or environmental transition; it constitutes a fundamental reconfiguration of global power dynamics that will reshape international relations, economic structures, and geopolitical alliances for decades to come. While much attention has focused on the climate and environmental benefits of green energy technologies, the strategic implications of this transformation are only beginning to be fully understood and theorized by political scientists, economists, and international relations experts.

The current global energy system, built over more than a century, has created a distinctive geopolitical architecture characterized by resource concentration, chokepoint vulnerabilities, and an asymmetric distribution of power between energy producers and consumers. Oil and natural gas reserves are geographically concentrated, with the Middle East holding approximately 48% of proven oil reserves and Russia, Iran, and Qatar controlling nearly 50% of global natural gas reserves. This geographical concentration has conferred enormous strategic leverage on producer states, enabling them to wield energy as both an economic commodity and a geopolitical weapon. The ability to threaten supply disruptions or manipulate prices has long been a cornerstone of resource nationalism and petrostate foreign policy, much like the role of digital transformation in global trade has reshaped economic relationships between nations.

Renewable energy fundamentally disrupts this paradigm. Solar and wind resources, while varying in intensity across regions, are far more geographically dispersed than fossil fuels. Every nation has access to some combination of solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric, or other renewable resources within its borders. This democratization of energy production has profound implications for energy security and national sovereignty. Countries currently dependent on energy imports could theoretically achieve energy independence through domestic renewable development, diminishing the leverage of traditional energy exporters and reducing vulnerability to supply disruptions or price manipulation.

However, the transition to renewables creates new dependencies and strategic vulnerabilities centered on critical minerals and manufacturing capacity. The production of solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electric vehicles requires substantial quantities of lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earth elements, and other materials. Unlike fossil fuels, which are consumed when used, these materials are embedded in durable infrastructure and potentially recyclable, but initial deployment requires enormous material throughput. Current estimates suggest that achieving global climate targets will require a four-to-six-fold increase in mineral production by 2040, creating what some analysts term a “mineral supercycle.”

The geographical distribution of these critical minerals is, in some cases, even more concentrated than fossil fuels. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt, China controls over 60% of rare earth element production, and Chile and Australia dominate lithium production. This concentration creates potential chokepoints and raises concerns about supply security, particularly given the political instability in some resource-rich regions and the potential for producer countries to exercise strategic resource withholding analogous to OPEC’s historical oil embargoes.

Hoạt động khai thác khoáng sản quan trọng phục vụ công nghệ năng lượng tái tạo

Hoạt động khai thác khoáng sản quan trọng phục vụ công nghệ năng lượng tái tạo

China’s dominance in renewable energy supply chains represents a particularly significant geopolitical dimension of the energy transition. Chinese companies control approximately 72% of global solar cell manufacturing capacity, 69% of lithium-ion battery production, and substantial shares of wind turbine and electric vehicle manufacturing. This industrial concentration has emerged through deliberate strategic policy, with the Chinese government providing extensive subsidies, coordinated planning, and protected domestic markets to build national champions in clean energy industries. China has also secured long-term supply agreements for critical minerals through bilateral deals and investments in mining operations across Africa, Latin America, and Australia, creating a vertically integrated supply chain from raw materials to finished products.

For Western nations and other industrialized economies, this situation presents a strategic dilemma reminiscent of oil dependence in the 20th century. Having recognized the geopolitical vulnerabilities created by fossil fuel imports, these countries now confront potential dependence on Chinese manufacturing and Chinese-controlled mineral supply chains for clean energy infrastructure. This concern has catalyzed various policy responses, including the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act, the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act, and initiatives to develop alternative supply chains through partnerships with allies like Australia, Canada, and countries in Latin America.

The decentralized nature of renewable energy also has implications for state capacity and political structures within nations. Fossil fuel production is generally capital-intensive and geographically concentrated in specific fields or mines, making it relatively easy for governments to control, regulate, and tax. This has contributed to the “resource curse” phenomenon, where countries rich in oil or minerals often develop authoritarian political systems, weak institutions, and rent-seeking economies dependent on resource exports. Distributed renewable energy, by contrast, is harder to monopolize or control centrally, potentially enabling more decentralized economic structures and reducing government resource rents.

Some political scientists hypothesize that this could weaken authoritarian petrostates as their primary source of revenue and geopolitical leverage diminishes, similar to how green buildings are promoting sustainable urban living through decentralized, community-based approaches. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 economic diversification program and similar initiatives in other Gulf states reflect awareness of this vulnerability. However, the transition’s speed and timing remain uncertain, and fossil fuel exporters may retain significant influence for decades, particularly if they successfully develop alternative economic models or leverage their financial resources accumulated during the fossil fuel era.

The renewable energy transition also intersects with broader technological competitions and standards-setting that carry geopolitical weight. Control over intellectual property, technical standards, and digital infrastructure associated with smart grids, energy storage, and electric mobility could confer strategic advantages. The integration of renewable energy with digital technologies creates cybersecurity concerns, as interconnected energy systems become potential targets for cyberattacks that could disrupt electricity supplies across wide areas. Nations are increasingly viewing energy infrastructure resilience through a security lens, incorporating considerations of supply chain security, cyber defense, and technological sovereignty.

Furthermore, the uneven pace of the energy transition across different regions creates new fault lines in international relations. Developed nations, having industrialized using fossil fuels, now advocate for rapid global decarbonization, while many developing countries argue for their right to exploit domestic fossil resources for economic development, citing principles of equity and historical responsibility for cumulative emissions. The allocation of climate finance, technology transfer, and support for just transitions in fossil-fuel-dependent economies represents a continuing source of North-South tension in climate negotiations, with implications for broader geopolitical alignment. These challenges mirror those seen in what are the challenges of sustainable agriculture in the 21st century?, where developed and developing nations have different priorities and capabilities.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, the Middle East and Russia together control approximately what percentage of global oil and gas reserves?

A. 48%

B. 50%

C. More than 70%

D. The passage does not specify an exact combined figure -

The author suggests that renewable energy represents a “democratization of energy production” because

A. it is cheaper than fossil fuels

B. resources are more widely distributed geographically

C. governments can control it more easily

D. it reduces environmental pollution -

Which country produces approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt?

A. China

B. Chile

C. Australia

D. Democratic Republic of Congo -

China’s dominance in renewable energy supply chains has been achieved through

A. natural resource abundance

B. deliberate strategic policy and government support

C. technological innovations

D. international cooperation agreements -

The “resource curse” phenomenon refers to countries that

A. have abundant renewable energy resources

B. develop authoritarian systems despite mineral wealth

C. suffer from lack of natural resources

D. export clean energy technologies

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each statement (32-36) with the correct region or country (A-H). You may use any letter more than once.

A. China

B. Saudi Arabia

C. United States

D. Democratic Republic of Congo

E. European Union

F. Middle East

G. Chile

H. Australia

- Has implemented Vision 2030 as an economic diversification program __

- Holds approximately 48% of proven oil reserves __

- Controls over 60% of rare earth element production __

- Has introduced the Inflation Reduction Act to address supply chain vulnerabilities __

- Dominates lithium production along with another country __

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

-

By what year do estimates suggest mineral production must increase four-to-six-fold to meet climate targets?

-

What percentage of global solar cell manufacturing capacity do Chinese companies control?

-

What type of economic structures does distributed renewable energy potentially enable compared to fossil fuels?

-

What type of attacks are interconnected energy systems potentially vulnerable to according to the passage?

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- C

- B

- C

- C

- B

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- FALSE

- TRUE

- intermittent

- energy storage systems / battery storage technology

- water

- source of electricity / electricity source

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- NO

- YES

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- NO

- iii

- iv

- vi

- vii

- rotor blades

- lift

- an Airbus A380 / the wingspan

- weather forecasting / advanced forecasting

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- D

- B

- D

- B

- B

- B

- F

- A

- C

- G (hoặc H)

- 2040

- 72% / approximately 72%

- decentralized economic structures

- cyberattacks

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: solar panels, 1950s, primarily used

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “early solar panels were prohibitively expensive… made them economically unviable for most applications except in remote locations where connecting to the electricity grid was impossible.” Đây là paraphrase của “remote locations” trong đáp án C.

Câu 3: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: China’s entry, significant

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, toàn đoạn

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn giải thích chi tiết “Chinese manufacturers invested heavily in production capacity… resulted in a dramatic reduction in panel prices – from around $76 per watt in 1977 to less than $0.30 per watt by 2020.” Đây chính là việc giảm chi phí sản xuất đáng kể (reduced production costs substantially).

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Bell Laboratories, first solar panel, 1950s

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “The journey began in the 1950s when scientists at Bell Laboratories created the first practical photovoltaic cell” – thông tin khớp chính xác với câu hỏi.

Câu 8: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Solar energy, air pollution, operation

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “They also produce no air pollution during operation” – điều này trái ngược hoàn toàn với câu phát biểu, do đó đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 10: intermittent

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: integration, challenging, solar energy

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Solar energy is intermittent – it only generates power when the sun is shining” – từ “intermittent” xuất hiện ngay trong ngữ cảnh được hỏi.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Wind power, longer history, solar power

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Unlike solar power, which has ancient applications primarily in heating and lighting, wind power for electricity generation is a relatively recent development” – câu này cho thấy solar power có lịch sử lâu hơn, trái ngược với câu phát biểu.

Câu 15: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: offshore wind turbines, 15,000 homes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “Today’s offshore wind turbines… can produce 15 megawatts or more, enough to power approximately 15,000 homes” – thông tin khớp chính xác.

Câu 19: iii (Paragraph 3)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Giải thích: Đoạn 3 tập trung vào việc so sánh kích thước và công suất của turbines từ những năm 1980 (15 mét, 50 kilowatts) với hiện tại (220 mét, 15 megawatts), minh họa “three-hundredfold increase in capacity” – rõ ràng nói về cải thiện đáng kể về kích thước và công suất.

Câu 20: iv (Paragraph 5)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Giải thích: Đoạn này thảo luận về “intermittency of wind power” và các giải pháp như “geographic diversification,” “weather forecasting models,” và “battery storage systems” – tất cả đều giải quyết thách thức về sự biến đổi của gió.

Câu 23: rotor blades

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “the rotor blades that capture wind energy” – cụm từ chính xác xuất hiện trong bài.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Middle East, Russia, percentage

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2

- Giải thích: Bài chỉ đưa ra số liệu riêng lẻ: “Middle East holding approximately 48% of proven oil reserves and Russia, Iran, and Qatar controlling nearly 50% of global natural gas reserves.” Không có con số kết hợp cụ thể, do đó đáp án D đúng.

Câu 28: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: democratization of energy production

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3

- Giải thích: “Solar and wind resources… are far more geographically dispersed than fossil fuels. Every nation has access to some combination… This democratization of energy production…” – rõ ràng liên kết việc phân bố địa lý rộng rãi với khái niệm dân chủ hóa.

Câu 32: B (Saudi Arabia)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9

- Giải thích: “Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 economic diversification program” được nhắc đến rõ ràng.

Câu 34: A (China)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3

- Giải thích: “China controls over 60% of rare earth element production” – thông tin khớp chính xác.

Câu 37: 2040

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: “Current estimates suggest that achieving global climate targets will require a four-to-six-fold increase in mineral production by 2040” – năm 2040 là câu trả lời.

Câu 40: cyberattacks

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: “interconnected energy systems become potential targets for cyberattacks” – từ “cyberattacks” xuất hiện chính xác trong ngữ cảnh này.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mainstream | adj | /ˈmeɪnstriːm/ | chủ đạo, phổ biến | solar power becoming a mainstream power source | mainstream media, mainstream culture |

| prohibitively | adv | /prəˈhɪbɪtɪvli/ | một cách cấm đoán, quá đắt | early solar panels were prohibitively expensive | prohibitively expensive, prohibitively high cost |

| photovoltaic | adj | /ˌfəʊtəʊvɒlˈteɪɪk/ | quang điện | first practical photovoltaic cell | photovoltaic cell, photovoltaic system |

| subsidies | n | /ˈsʌbsɪdiz/ | trợ cấp, tiền trợ giúp | government subsidies and incentives | government subsidies, agricultural subsidies |

| economies of scale | phrase | /ɪˈkɒnəmiz əv skeɪl/ | hiệu quả kinh tế nhờ quy mô | economies of scale began to take effect | achieve economies of scale |

| game-changer | n | /ˈɡeɪm tʃeɪndʒə(r)/ | yếu tố thay đổi cuộc chơi | China’s entry proved to be a game-changer | become a game-changer, potential game-changer |

| precipitous | adj | /prɪˈsɪpɪtəs/ | dốc đứng, đột ngột | such a precipitous decline | precipitous drop, precipitous fall |

| conversion efficiency | phrase | /kənˈvɜːʃn ɪˈfɪʃnsi/ | hiệu suất chuyển đổi | conversion efficiencies of only 6% | improve conversion efficiency |

| intermittent | adj | /ˌɪntəˈmɪtənt/ | không liên tục, gián đoạn | solar energy is intermittent | intermittent problems, intermittent supply |

| variability | n | /ˌveəriəˈbɪləti/ | tính biến đổi | this variability initially made it difficult | weather variability, price variability |

| baseload | adj | /ˈbeɪsləʊd/ | tải cơ sở (năng lượng) | more reliable baseload power source | baseload power, baseload capacity |

| net positive energy | phrase | /net ˈpɒzətɪv ˈenədʒi/ | năng lượng dương ròng | generate net positive energy | achieve net positive energy |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cornerstone | n | /ˈkɔːnəstəʊn/ | nền tảng, trụ cột | cornerstone of the global transition | cornerstone of policy, cornerstone principle |

| exponential | adj | /ˌekspəˈnenʃl/ | theo cấp số nhân | exponential growth since the 1980s | exponential growth, exponential increase |

| scalable | adj | /ˈskeɪləbl/ | có thể mở rộng quy mô | scalable potential of renewable energy | scalable solution, scalable technology |

| deceptively | adv | /dɪˈseptɪvli/ | có vẻ (nhưng thực tế khác) | deceptively simple principle | deceptively simple, deceptively easy |

| kinetic energy | phrase | /kɪˈnetɪk ˈenədʒi/ | động năng | moving air possesses kinetic energy | convert kinetic energy, harness kinetic energy |

| aerodynamic | adj | /ˌeərəʊdaɪˈnæmɪk/ | khí động học | aerodynamically designed blades | aerodynamic design, aerodynamic efficiency |

| rotor diameter | phrase | /ˈrəʊtə daɪˈæmɪtə(r)/ | đường kính cánh quạt | rotor diameters of approximately 15 meters | increase rotor diameter |

| land-use conflict | phrase | /lænd juːs ˈkɒnflɪkt/ | xung đột sử dụng đất | avoid land-use conflicts | resolve land-use conflicts |

| corrosive | adj | /kəˈrəʊsɪv/ | ăn mòn | corrosive marine environment | corrosive effect, corrosive substance |

| mitigate | v | /ˈmɪtɪɡeɪt/ | giảm thiểu | technological strategies have mitigated this concern | mitigate risk, mitigate impact |

| penetration rate | phrase | /ˌpenɪˈtreɪʃn reɪt/ | tỷ lệ thâm nhập | high penetration rates of wind power | market penetration rate |

| levelized cost | phrase | /ˈlevəlaɪzd kɒst/ | chi phí san bằng | levelized cost of energy (LCOE) | calculate levelized cost |

| life cycle assessment | phrase | /laɪf ˈsaɪkl əˈsesmənt/ | đánh giá vòng đời | life cycle assessments indicate | conduct life cycle assessment |

| recoup | v | /rɪˈkuːp/ | lấy lại, bù đắp | recoup the energy invested | recoup investment, recoup losses |

| predictive maintenance | phrase | /prɪˈdɪktɪv ˈmeɪntənəns/ | bảo trì dự đoán | optimizing through predictive maintenance | implement predictive maintenance |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paradigm shift | phrase | /ˈpærədaɪm ʃɪft/ | sự thay đổi mô hình | paradigm shift from fossil fuel dependency | undergo paradigm shift |

| reconfiguration | n | /riːkənˌfɪɡəˈreɪʃn/ | sự cấu hình lại | fundamental reconfiguration of global power | require reconfiguration |

| geopolitical | adj | /ˌdʒiːəʊpəˈlɪtɪkl/ | địa chính trị | geopolitical implications | geopolitical risk, geopolitical tensions |

| asymmetric | adj | /ˌæsɪˈmetrɪk/ | bất đối xứng | asymmetric distribution of power | asymmetric information, asymmetric warfare |

| strategic leverage | phrase | /strəˈtiːdʒɪk ˈliːvərɪdʒ/ | đòn bẩy chiến lược | enormous strategic leverage | gain strategic leverage |

| petrostate | n | /ˈpetrəʊsteɪt/ | quốc gia dầu mỏ | petrostate foreign policy | wealthy petrostate |

| democratization | n | /dɪˌmɒkrətaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | dân chủ hóa | democratization of energy production | promote democratization |

| critical minerals | phrase | /ˈkrɪtɪkl ˈmɪnərəlz/ | khoáng sản quan trọng | centered on critical minerals | secure critical minerals |

| material throughput | phrase | /məˈtɪəriəl ˈθruːpʊt/ | lượng vật liệu qua | enormous material throughput | increase material throughput |

| mineral supercycle | phrase | /ˈmɪnərəl ˈsuːpəsaɪkl/ | chu kỳ siêu khoáng sản | creating a “mineral supercycle” | enter mineral supercycle |

| chokepoint | n | /ˈtʃəʊkpɔɪnt/ | điểm nghẽn | creates potential chokepoints | strategic chokepoint |

| vertically integrated | adj phrase | /ˈvɜːtɪkli ˈɪntɪɡreɪtɪd/ | tích hợp theo chiều dọc | vertically integrated supply chain | become vertically integrated |

| resource curse | phrase | /rɪˈsɔːs kɜːs/ | lời nguyền tài nguyên | resource curse phenomenon | suffer from resource curse |

| rent-seeking | adj | /rent ˈsiːkɪŋ/ | tìm kiếm lợi nhuận đặc quyền | rent-seeking economies | rent-seeking behavior |

| decarbonization | n | /diːˌkɑːbənaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | khử carbon | rapid global decarbonization | achieve decarbonization |

| technological sovereignty | phrase | /ˌteknəˈlɒdʒɪkl ˈsɒvrənti/ | chủ quyền công nghệ | considerations of technological sovereignty | maintain technological sovereignty |

| fault lines | phrase | /fɔːlt laɪnz/ | đường đứt gãy, ranh giới | creates new fault lines | expose fault lines |

| historical responsibility | phrase | /hɪˈstɒrɪkl rɪˌspɒnsəˈbɪləti/ | trách nhiệm lịch sử | principles of historical responsibility | acknowledge historical responsibility |

Kết bài

Chủ đề “The rise of green energy technologies” không chỉ là một xu hướng tạm thời mà đã trở thành trọng tâm trong các kỳ thi IELTS Reading hiện đại. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu hoàn chỉnh này, bạn đã được trải nghiệm ba passages với độ khó tăng dần, từ những khái niệm cơ bản về năng lượng mặt trời trong Passage 1, đến các thách thức kỹ thuật và kinh tế của năng lượng gió trong Passage 2, và cuối cùng là những phân tích sâu sắc về tác động địa chính trị của chuyển đổi năng lượng xanh trong Passage 3.

Bộ đề thi này đã cung cấp đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng khác nhau, giúp bạn làm quen với mọi format có thể xuất hiện trong bài thi thực tế. Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích không chỉ giúp bạn kiểm tra kết quả mà còn hiểu được logic làm bài, cách xác định từ khóa và kỹ thuật paraphrase – những yếu tố quyết định để đạt band điểm cao.

Đặc biệt, phần từ vựng được tổng hợp theo từng passage sẽ giúp bạn xây dựng vốn từ vựng học thuật quan trọng, không chỉ cho phần Reading mà còn hỗ trợ cho cả Writing và Speaking. Hãy học những từ này trong ngữ cảnh và thực hành sử dụng chúng thường xuyên.

Để đạt hiệu quả tối ưu, bạn nên làm bài trong điều kiện giống thi thật: đặt thời gian 60 phút, không tra từ điển, và hoàn thành cả 3 passages trước khi xem đáp án. Sau đó, dành thời gian phân tích kỹ những câu sai để hiểu rõ nguyên nhân và cải thiện cho lần sau. Chúc bạn luyện tập hiệu quả và đạt band điểm IELTS Reading như mong muốn!