Mở bài

Chủ đề “The Role Of Education In Promoting Sustainable Practices” (Vai trò của giáo dục trong thúc đẩy thực hành bền vững) là một trong những chủ đề xuất hiện thường xuyên nhất trong kỳ thi IELTS Reading, đặc biệt trong các đề thi gần đây. Chủ đề này kết hợp giữa giáo dục, môi trường và phát triển xã hội – ba lĩnh vực được IELTS ưa chuộng.

Trong bài viết này, bạn sẽ được trải nghiệm một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với ba passages từ dễ đến khó, phản ánh đúng cấu trúc đề thi thật. Cụ thể, bạn sẽ học được:

- Đề thi đầy đủ 3 passages: Passage 1 (Easy – Band 5.0-6.5), Passage 2 (Medium – Band 6.0-7.5), và Passage 3 (Hard – Band 7.0-9.0)

- 40 câu hỏi đa dạng: Bao gồm 7-8 dạng câu hỏi khác nhau giống thi thật 100%

- Đáp án chi tiết: Kèm giải thích vị trí, paraphrase và chiến lược làm bài

- Từ vựng học thuật: Hơn 100 từ vựng quan trọng được phân tích kỹ lưỡng

- Kỹ thuật làm bài: Tips thực chiến từ kinh nghiệm 20 năm giảng dạy

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với áp lực thời gian và độ khó thực tế của IELTS Reading.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

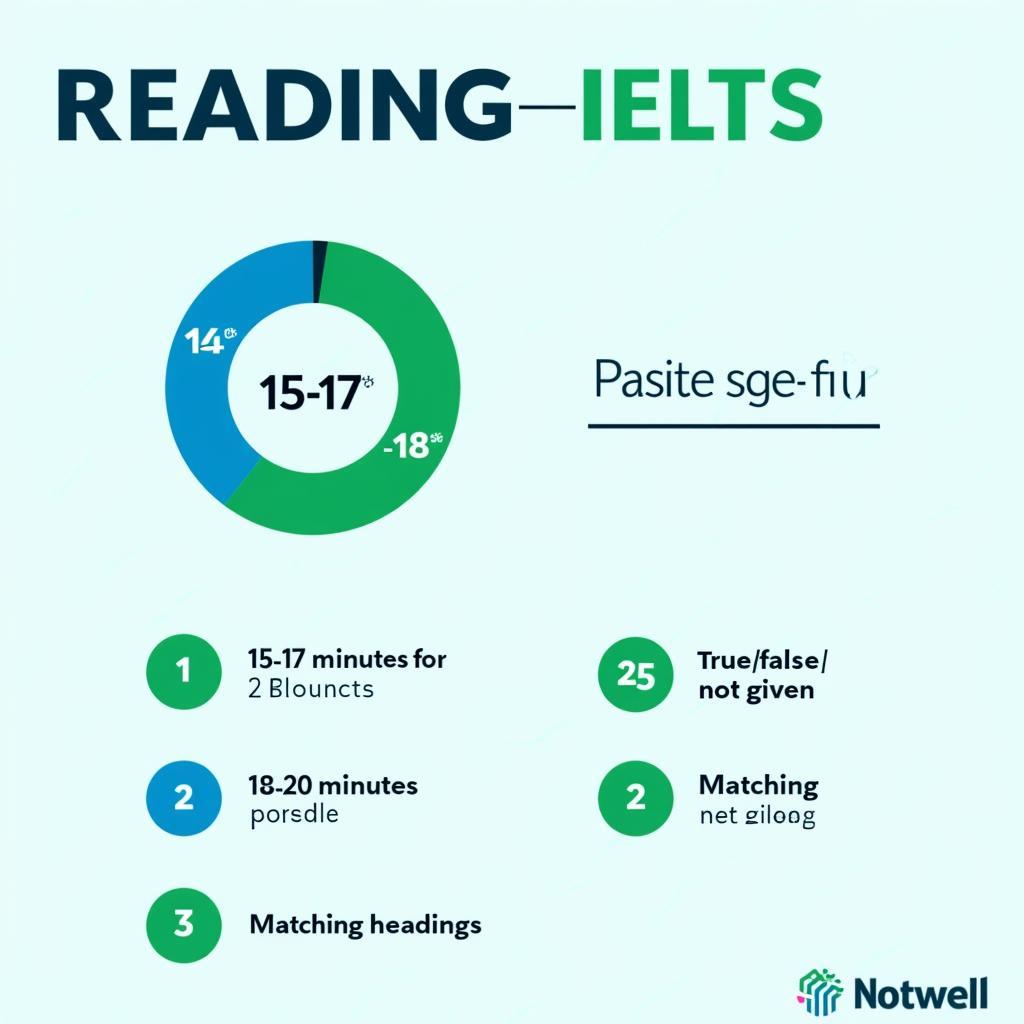

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Điểm đặc biệt là bạn không có thời gian riêng để chuyển đáp án sang answer sheet, vì vậy cần quản lý thời gian thật tốt.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó thấp nhất)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao nhất)

Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được 1 điểm, không trừ điểm cho câu sai. Số điểm thô (raw score) sau đó được quy đổi sang band điểm từ 0-9.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không có

- Yes/No/Not Given – Xác định quan điểm tác giả

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu

- Summary Completion – Hoàn thành tóm tắt

- Short-answer Questions – Câu hỏi trả lời ngắn

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Education as a Catalyst for Environmental Change

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The relationship between education and sustainable development has become increasingly important in the 21st century. As environmental challenges such as climate change, pollution, and resource depletion continue to threaten our planet, educators worldwide are recognizing their crucial role in shaping a more sustainable future. Educational institutions, from primary schools to universities, are now incorporating sustainability principles into their curricula, teaching students not only about environmental issues but also about practical solutions they can implement in their daily lives.

Environmental education began gaining momentum in the 1970s, following the first Earth Day celebrations and growing public awareness of ecological problems. However, early approaches often focused solely on teaching scientific facts about nature and pollution. Today’s educational paradigm has evolved significantly, emphasizing critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and active participation in sustainability initiatives. Students are no longer passive recipients of information; they are encouraged to become agents of change within their communities.

One of the most effective approaches to promoting sustainable practices through education is experiential learning. This method involves hands-on activities that allow students to directly engage with environmental issues. For example, many schools have established school gardens where children learn about organic farming, composting, and the importance of local food systems. These gardens serve multiple purposes: they provide fresh produce for school meals, teach students about nutrition and food security, and demonstrate how individual actions can contribute to environmental sustainability. Research has shown that students who participate in such programs are more likely to adopt eco-friendly behaviors at home and influence their families’ consumption patterns.

Another crucial aspect of education for sustainability is developing students’ understanding of the interconnectedness between environmental, social, and economic systems. This holistic approach helps learners recognize that sustainability is not just about protecting nature; it also involves ensuring social equity, economic viability, and cultural preservation. For instance, when studying renewable energy, students might explore not only the technological aspects but also the social implications of transitioning away from fossil fuels, including job creation in green industries and the need for just transitions that support workers in traditional energy sectors.

Digital technology has opened new avenues for environmental education. Online platforms, virtual reality experiences, and mobile applications enable students to explore ecosystems they might never visit in person, track their carbon footprint, and connect with peers globally to share sustainability initiatives. Social media campaigns led by students have raised awareness about issues ranging from plastic pollution to deforestation, demonstrating the power of educated youth to influence public discourse and policy decisions.

The role of teachers in this educational transformation cannot be overstated. Educators must be adequately trained to integrate sustainability concepts across different subjects, not just in science classes. A mathematics lesson might involve calculating the energy savings from using LED bulbs, while a literature class could explore environmental themes in contemporary fiction. This cross-curricular approach ensures that students encounter sustainability principles repeatedly throughout their education, reinforcing their importance and relevance to all aspects of life.

Community engagement represents another vital component of education for sustainability. When schools partner with local organizations, businesses, and government agencies, students gain real-world perspectives on environmental challenges and solutions. These partnerships can take various forms: internships with environmental organizations, participation in community clean-up projects, or collaboration with local businesses to reduce waste. Such experiences help students understand that sustainable development requires collective action and that their individual efforts, while important, are most effective when combined with broader systemic changes.

Assessment methods in sustainability education have also evolved. Rather than relying solely on traditional tests, educators now use project-based assessments that evaluate students’ ability to apply their knowledge to real situations. Students might be asked to develop a sustainability plan for their school, design a campaign to reduce single-use plastics in their community, or create a business proposal for an eco-friendly product. These assessments not only measure learning but also empower students to see themselves as capable of creating positive change.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, environmental education in the 1970s primarily focused on:

- A) Critical thinking skills

- B) Scientific facts about nature

- C) Community engagement

- D) Digital technology

-

School gardens serve all of the following purposes EXCEPT:

- A) Providing food for school meals

- B) Teaching about nutrition

- C) Demonstrating eco-friendly behaviors

- D) Training professional farmers

-

The passage suggests that a holistic approach to sustainability education includes:

- A) Only environmental protection

- B) Environmental, social, and economic factors

- C) Exclusively technological solutions

- D) Just renewable energy systems

-

Digital technology in environmental education allows students to:

- A) Replace all classroom learning

- B) Avoid studying difficult topics

- C) Explore distant ecosystems virtually

- D) Eliminate the need for teachers

-

Modern assessment methods in sustainability education emphasize:

- A) Only traditional testing

- B) Memorization of facts

- C) Project-based applications

- D) Individual competition

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information in the passage?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

Students who participate in school garden programs tend to influence their families’ habits.

-

All teachers currently receive adequate training in sustainability education.

-

Mathematics lessons cannot effectively incorporate sustainability concepts.

-

Community partnerships help students understand the need for collective action.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

Early environmental education focused on teaching facts rather than developing __ in students.

-

Students are now encouraged to become __ within their communities.

-

A cross-curricular approach ensures students encounter sustainability principles across __.

-

Project-based assessments empower students to see themselves as capable of creating __.

PASSAGE 2 – Transforming Educational Systems for a Sustainable Future

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The paradigm shift toward education for sustainable development (ESD) represents one of the most significant transformations in modern pedagogical theory and practice. This shift, championed by UNESCO and adopted by educational systems worldwide, moves beyond traditional environmental literacy to embrace a more comprehensive framework that addresses the multidimensional challenges of the 21st century. ESD aims to equip learners with the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes necessary to contribute to a more sustainable and equitable world, recognizing that education is not merely about knowledge transmission but about fostering transformative learning experiences that challenge existing worldviews and inspire innovative solutions.

The theoretical foundation of ESD draws from multiple disciplines, including environmental science, sociology, economics, and psychology. Constructivist learning theories emphasize that learners actively construct knowledge through experience and reflection rather than passively receiving information. This perspective aligns perfectly with sustainability education, which requires students to grapple with complex, ill-defined problems that lack simple solutions. For instance, when examining issues like urban sustainability, students must consider competing interests—economic development, environmental conservation, social justice, and cultural preservation—and develop the capacity for systems thinking that recognizes how actions in one domain affect others.

Critical pedagogy, another influential theoretical framework, emphasizes the role of education in promoting social justice and empowering marginalized communities. This approach is particularly relevant to sustainability education because environmental degradation disproportionately affects vulnerable populations who often have the least responsibility for creating these problems. By incorporating critical pedagogy into ESD, educators help students understand the power dynamics and structural inequalities that perpetuate unsustainable practices. Students learn to question dominant narratives about progress and development, examining whose interests are served by current economic systems and whose voices are excluded from decision-making processes.

Học sinh đang tích cực tham gia dự án giáo dục bền vững tại trường học với hoạt động thực hành

Học sinh đang tích cực tham gia dự án giáo dục bền vững tại trường học với hoạt động thực hành

The implementation of ESD varies considerably across different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. In developed nations, educational initiatives often focus on reducing overconsumption, promoting circular economy principles, and transitioning to low-carbon lifestyles. Schools in countries like Finland, Denmark, and Japan have integrated sustainability across their entire curricula, with students regularly engaging in energy audits, waste reduction projects, and biodiversity conservation activities. These countries also emphasize outdoor education and connection with nature, recognizing that environmental stewardship develops through direct experience and emotional connection rather than solely through intellectual understanding.

In developing countries, ESD takes different forms, often addressing more immediate concerns related to poverty alleviation, food security, and access to clean water and sanitation. Educational programs in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia frequently combine literacy education with practical skills training in sustainable agriculture, water management, and renewable energy technologies. These programs recognize that sustainable development cannot be achieved without addressing basic human needs and economic opportunities. Moreover, they often build upon traditional ecological knowledge held by indigenous communities, validating and preserving wisdom that has enabled sustainable resource management for generations.

The role of higher education in advancing sustainability deserves particular attention. Universities worldwide are increasingly recognizing their responsibility not only to teach about sustainability but to model sustainable practices in their operations. The campus-as-laboratory approach transforms university facilities into living laboratories where students can observe, measure, and improve sustainability performance. Students might collaborate with facilities managers to optimize energy efficiency, work with dining services to reduce food waste, or partner with transportation departments to promote alternative mobility options. These experiences provide invaluable opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge to real challenges, developing the problem-solving capabilities and collaborative skills essential for sustainability professionals.

Research universities also play a crucial role in generating new knowledge about sustainable practices and technologies. Interdisciplinary research centers bring together scholars from diverse fields to address complex sustainability challenges. For example, research on sustainable urban development might involve architects, engineers, urban planners, sociologists, and environmental scientists working collaboratively. This interdisciplinary approach mirrors the real-world complexity of sustainability issues and prepares students for careers in fields that increasingly require cross-disciplinary collaboration.

However, significant barriers impede the widespread adoption of ESD. Institutional inertia, resistance to curriculum change, and lack of teacher training represent persistent challenges. Many educational systems remain structured around disciplinary silos that make integrated, cross-curricular approaches difficult to implement. Additionally, standardized testing that focuses on narrow academic achievement can discourage the holistic, experiential learning that characterizes effective sustainability education. Teachers who wish to incorporate ESD often lack adequate support, resources, and professional development opportunities.

Funding constraints present another significant obstacle, particularly in resource-limited contexts. Implementing comprehensive sustainability programs requires investment in teacher training, curriculum development, educational materials, and often infrastructure improvements such as renewable energy systems or school gardens. Competing priorities and budgetary pressures mean that sustainability education may be deprioritized in favor of initiatives perceived as more directly related to academic achievement.

Despite these challenges, momentum for ESD continues to grow. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 which focuses on quality education, explicitly recognize education as fundamental to achieving all other sustainability objectives. International networks of educators, researchers, and policymakers are collaborating to share best practices, develop resources, and advocate for systemic changes that support sustainability education. As the urgency of environmental and social challenges becomes increasingly apparent, the recognition that education must play a central role in addressing these challenges strengthens.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in the passage?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Education for sustainable development is primarily about transmitting environmental facts to students.

-

Critical pedagogy helps students understand power structures that maintain unsustainable practices.

-

All developed nations have successfully integrated sustainability across their curricula.

-

Traditional ecological knowledge from indigenous communities can contribute to sustainable development education.

-

Standardized testing effectively measures the outcomes of sustainability education.

Questions 19-22: Matching Headings

The passage has nine paragraphs (Paragraphs 1-9).

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs 4-7 from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number (i-x) next to Questions 19-22.

List of Headings:

- i. The theoretical foundations of modern sustainability education

- ii. Financial obstacles to implementing sustainability programs

- iii. Sustainability education approaches in wealthy nations

- iv. Universities as models of sustainable practices

- v. The role of digital technology in education

- vi. Research contributions from higher education institutions

- vii. Sustainability education in less economically developed regions

- viii. International cooperation in environmental policy

- ix. Teacher resistance to new educational methods

- x. The future of online learning platforms

- Paragraph 4 __

- Paragraph 5 __

- Paragraph 6 __

- Paragraph 7 __

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Barriers to Education for Sustainable Development

Several obstacles prevent the widespread implementation of ESD. Many educational institutions suffer from 23) __ that makes curriculum reform difficult. The structure of education systems around 24) __ creates challenges for integrated approaches. Furthermore, 25) __ that emphasize narrow achievement discourage holistic learning methods. Many teachers lack adequate 26) __ to effectively implement sustainability education in their classrooms.

PASSAGE 3 – Neurocognitive Dimensions of Environmental Learning and Behavioral Transformation

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

Recent advances in neuroscience and cognitive psychology have illuminated the neurobiological mechanisms underlying environmental learning and the formation of pro-environmental behaviors, offering profound insights that can enhance the efficacy of sustainability education. Understanding how the brain processes environmental information, forms affective connections with nature, and translates knowledge into action provides educators with evidence-based strategies for designing more effective interventions. This neuroeducational approach represents a paradigmatic evolution beyond traditional behavioral change models, integrating insights from brain imaging studies, developmental neuroscience, and affective neuroscience to create educational experiences that align with the brain’s natural learning mechanisms.

Neuroplasticity—the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life—constitutes the fundamental biological substrate enabling behavioral transformation through education. Research utilizing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has demonstrated that sustained engagement with environmental concepts and sustainability practices produces measurable changes in brain structure and neural activation patterns. Studies have shown that individuals with extensive experience in nature-based activities exhibit enhanced gray matter density in regions associated with spatial cognition, emotional regulation, and perspective-taking. This neuroplastic adaptation suggests that environmental education can literally reshape the brain in ways that facilitate pro-environmental thinking and behavior.

The neuroscience of environmental awareness reveals the crucial role of the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, in processing environmental information. The amygdala, traditionally associated with threat detection and emotional processing, responds strongly to environmental stimuli that signal either danger or opportunity. Research indicates that environmental education programs that activate appropriate emotional responses—such as wonder, empathy, or concern—create stronger memory consolidation through amygdala-hippocampal interactions. However, this relationship is complex: excessive activation of fear circuits through apocalyptic messaging about environmental destruction can trigger defensive avoidance rather than constructive engagement, as the brain’s threat response system promotes escape rather than approach behaviors.

Minh họa kết nối não bộ và quá trình học tập về môi trường bền vững

Minh họa kết nối não bộ và quá trình học tập về môi trường bền vững

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), humanity’s most recently evolved brain region, plays a pivotal role in translating environmental knowledge into intentional action. The PFC orchestrates executive functions including planning, decision-making, impulse control, and the ability to delay gratification—all essential for sustainable behaviors that often require forgoing immediate pleasures for long-term collective benefits. Neuroimaging research has revealed that pro-environmental decision-making activates the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), particularly when individuals must balance personal interests against environmental concerns. Educational interventions that strengthen PFC function through practices like reflective thinking, scenario planning, and values clarification may enhance individuals’ capacity for sustainable decision-making.

The emerging field of contemplative neuroscience offers particularly relevant insights for environmental education. Research on mindfulness meditation and nature-based contemplative practices demonstrates their capacity to modulate activity in the default mode network (DMN)—a set of brain regions active during self-referential thinking and mind-wandering. Hyperactivity in the DMN has been associated with rumination, anxiety, and an excessively individualistic self-concept. Contemplative practices that emphasize present-moment awareness and connection with nature can reduce DMN hyperactivity while strengthening salience network activation, potentially facilitating a shift from an anthropocentric to an ecocentric worldview. Some educational programs now integrate mindfulness-based environmental education, combining traditional ecological knowledge with contemplative practices to foster what researchers term “ecological self“—an identity construct that includes the natural world within one’s sense of self.

Social neuroscience elucidates the neural mechanisms through which social influences shape environmental attitudes and behaviors. The discovery of mirror neuron systems—networks that activate both when performing actions and when observing others perform them—helps explain how social modeling influences behavioral adoption. When students observe teachers, peers, or role models engaging in sustainable practices, their mirror neuron systems create neural simulations of these behaviors, facilitating observational learning and increasing the likelihood of behavioral imitation. Furthermore, research on the neural correlates of social conformity reveals that adopting behaviors consistent with one’s social group activates the brain’s reward circuitry, releasing dopamine and creating positive reinforcement. Educational strategies that leverage peer influence and create social norms favoring sustainability can thus harness these neurobiological mechanisms to promote behavioral change.

The role of emotional engagement in environmental learning has received increasing attention from affective neuroscience. Research distinguishes between cognitive empathy (understanding others’ perspectives) and affective empathy (sharing others’ emotions), demonstrating that both are mediated by distinct though interconnected neural networks. Effective environmental education activates both forms of empathy, helping students intellectually understand how environmental degradation affects different populations while also emotionally connecting with those impacts. Studies using fMRI have shown that narratives about environmental victims activate the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex—regions associated with empathy and compassion—more strongly than abstract statistics, even when the statistical information represents greater harm. This finding has significant pedagogical implications, suggesting that personalized narratives and direct encounters with affected individuals or ecosystems create stronger motivation for pro-environmental action than data alone.

Developmental neuroscience provides insights into age-appropriate approaches to environmental education. The protracted maturation of the prefrontal cortex, which continues developing into the mid-twenties, has implications for when and how certain sustainability concepts should be introduced. Young children, whose PFC development is incomplete, may struggle with abstract temporal reasoning required to understand long-term environmental consequences. However, their developing brains show heightened sensitivity to sensory experiences and emotional learning, making direct nature experiences and emotionally-engaged storytelling particularly effective. Adolescents, experiencing heightened reward sensitivity and increased responsiveness to social influences due to pubertal changes in the brain’s reward system, may be especially motivated by peer-led initiatives and opportunities for visible impact that generate social recognition.

The cognitive barriers to pro-environmental behavior—including temporal discounting (valuing immediate rewards over future benefits), psychological distance (perceiving environmental issues as distant in time, space, or social relevance), and cognitive dissonance (discomfort from contradiction between beliefs and behaviors)—all have neurobiological correlates that education can address. Temporal discounting, for instance, reflects competition between the limbic system’s preference for immediate rewards and the PFC’s capacity for future-oriented thinking. Educational strategies that make future consequences more psychologically proximal and emotionally salient—through visualization exercises, scenario planning, or virtual reality experiences—can strengthen PFC engagement and reduce temporal discounting. Similarly, addressing psychological distance by connecting global environmental issues to local impacts activates personal relevance networks in the brain, enhancing attention, memory, and motivation.

Emerging research on the neuroscience of hope and self-efficacy offers crucial insights for avoiding the paralysis that can result from overwhelming environmental information. Studies demonstrate that hope—defined as goal-directed thinking involving both pathways (strategies for achieving goals) and agency (belief in one’s capacity to use those pathways)—activates prefrontal regions associated with goal pursuit while modulating amygdala activity that might otherwise trigger anxiety or despair. Educational programs that balance information about environmental challenges with concrete action opportunities, skill development, and success stories appear to maintain neural activation patterns conducive to sustained engagement rather than defensive avoidance or resigned acceptance. The neurobiology of hope suggests that effective environmental education must simultaneously engage the cognitive systems that understand problems, the emotional systems that care about solutions, and the motivational systems that believe in the possibility of positive change.

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

-

According to the passage, neuroplasticity suggests that environmental education can:

- A) Only affect children’s brains

- B) Physically alter brain structure

- C) Reduce gray matter density

- D) Eliminate emotional responses

-

The passage indicates that excessive use of apocalyptic messaging in environmental education:

- A) Creates the strongest memory consolidation

- B) Activates constructive engagement

- C) May trigger defensive avoidance

- D) Strengthens pro-environmental behaviors

-

Research on mirror neuron systems helps explain how:

- A) Students learn exclusively through reading

- B) Social modeling influences behavioral adoption

- C) Individual study is most effective

- D) Environmental knowledge is forgotten

-

According to the passage, personalized narratives about environmental victims:

- A) Are less effective than statistical data

- B) Activate empathy-related brain regions more strongly than statistics

- C) Should be avoided in environmental education

- D) Have no effect on brain activity

-

The neuroscience of hope suggests effective environmental education should:

- A) Focus only on environmental problems

- B) Avoid discussing solutions

- C) Balance challenges with action opportunities

- D) Emphasize despair to motivate change

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each brain region (A-F) with the correct function related to environmental education (Questions 32-36).

Brain Regions:

- A) Amygdala

- B) Prefrontal cortex

- C) Hippocampus

- D) Default mode network

- E) Mirror neuron system

- F) Anterior insula

-

Orchestrates planning and decision-making for sustainable behaviors __

-

Responds to environmental stimuli signaling danger or opportunity __

-

Facilitates observational learning through neural simulation __

-

Active during self-referential thinking; modulated by mindfulness __

-

Activated when experiencing empathy for environmental victims __

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

What term describes the brain’s capacity to reorganize by forming new neural connections?

-

What type of educational approach combines traditional ecological knowledge with meditation practices?

-

What process reflects competition between immediate rewards and future-oriented thinking?

-

What two components define hope as understood in neuroscience research?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- D

- B

- C

- C

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- FALSE

- TRUE

- critical thinking / problem-solving skills

- agents of change

- different subjects

- positive change

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- YES

- NO

- iii

- vii

- iv

- vi

- institutional inertia

- disciplinary silos

- standardized testing

- professional development / support / training

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- B

- B

- C

- B

- A

- E

- D

- F

- Neuroplasticity

- mindfulness-based environmental education

- temporal discounting

- pathways and agency

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B – Scientific facts about nature

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: environmental education, 1970s, primarily focused

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “early approaches often focused solely on teaching scientific facts about nature and pollution” (các phương pháp sớm thường chỉ tập trung vào việc dạy các sự thật khoa học về tự nhiên và ô nhiễm). Đây là paraphrase trực tiếp của đáp án B.

Câu 2: D – Training professional farmers

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice (EXCEPT)

- Từ khóa: school gardens, purposes

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-9

- Giải thích: Bài viết liệt kê các mục đích: cung cấp thực phẩm (A), dạy về dinh dưỡng (B), thể hiện hành vi thân thiện với môi trường (C). Không có thông tin nào về đào tạo nông dân chuyên nghiệp.

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: students, school garden programs, influence families

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 10-11

- Giải thích: “Research has shown that students who participate in such programs are more likely to adopt eco-friendly behaviors at home and influence their families’ consumption patterns” khớp với câu hỏi.

Câu 7: NOT GIVEN

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all teachers, adequate training

- Giải thích: Đoạn 6 chỉ nói giáo viên “must be adequately trained” (phải được đào tạo đầy đủ) nhưng không xác nhận liệu tất cả có được đào tạo hay không.

Câu 10: critical thinking / problem-solving skills

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: early environmental education, teaching facts, developing

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “Today’s educational paradigm has evolved significantly, emphasizing critical thinking, problem-solving skills” cho thấy sự tương phản với cách tiếp cận trước đó.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: ESD, primarily, transmitting environmental facts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Tác giả nói ESD “moves beyond traditional environmental literacy” và “not merely about knowledge transmission” – trái ngược với câu phát biểu.

Câu 15: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: critical pedagogy, power structures

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-8

- Giải thích: “educators help students understand the power dynamics and structural inequalities that perpetuate unsustainable practices” khớp với quan điểm tác giả.

Câu 19: iii – Sustainability education approaches in wealthy nations

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: Đoạn này bắt đầu bằng “In developed nations, educational initiatives often focus on…” và liệt kê các ví dụ từ Finland, Denmark, Nhật Bản.

Câu 20: vii – Sustainability education in less economically developed regions

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Headings

- Vị trí: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “In developing countries, ESD takes different forms” và đề cập đến Sub-Saharan Africa và South Asia.

Câu 23: institutional inertia

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: obstacles, educational institutions

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 2

- Giải thích: “Institutional inertia, resistance to curriculum change” được liệt kê đầu tiên trong các rào cản.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B – Physically alter brain structure

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: neuroplasticity, environmental education

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-7

- Giải thích: “sustained engagement with environmental concepts and sustainability practices produces measurable changes in brain structure” – thay đổi về cấu trúc não.

Câu 28: C – May trigger defensive avoidance

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: apocalyptic messaging

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 7-10

- Giải thích: “excessive activation of fear circuits through apocalyptic messaging about environmental destruction can trigger defensive avoidance rather than constructive engagement.”

Câu 32: B – Prefrontal cortex

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Features

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “The prefrontal cortex (PFC)…orchestrates executive functions including planning, decision-making.”

Câu 37: Neuroplasticity

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1

- Giải thích: Định nghĩa được đưa ra ngay đầu đoạn: “Neuroplasticity—the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections.”

Câu 40: pathways and agency

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “hope—defined as goal-directed thinking involving both pathways (strategies for achieving goals) and agency (belief in one’s capacity to use those pathways).”

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sustainable | adj | /səˈsteɪnəbl/ | bền vững | sustainable development | sustainable practices, sustainable future |

| depletion | n | /dɪˈpliːʃn/ | sự cạn kiệt | resource depletion | resource depletion, ozone depletion |

| paradigm | n | /ˈpærədaɪm/ | mô hình, mẫu hình | educational paradigm | paradigm shift, new paradigm |

| experiential | adj | /ɪkˌspɪəriˈenʃl/ | dựa trên trải nghiệm | experiential learning | experiential learning, experiential education |

| composting | n | /ˈkɒmpɒstɪŋ/ | ủ phân hữu cơ | learn about composting | composting system, home composting |

| interconnectedness | n | /ˌɪntəkəˈnektɪdnəs/ | sự liên kết lẫn nhau | understanding interconnectedness | recognize interconnectedness |

| holistic | adj | /həʊˈlɪstɪk/ | toàn diện | holistic approach | holistic approach, holistic view |

| renewable | adj | /rɪˈnjuːəbl/ | có thể tái tạo | renewable energy | renewable energy, renewable resources |

| carbon footprint | n | /ˈkɑːbən ˈfʊtprɪnt/ | dấu chân carbon | track carbon footprint | reduce carbon footprint, calculate footprint |

| deforestation | n | /diːˌfɒrɪˈsteɪʃn/ | nạn phá rừng | issues like deforestation | combat deforestation, prevent deforestation |

| cross-curricular | adj | /krɒs kəˈrɪkjʊlə/ | liên môn học | cross-curricular approach | cross-curricular integration |

| systemic | adj | /sɪˈstemɪk/ | hệ thống | systemic changes | systemic change, systemic approach |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pedagogical | adj | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkl/ | thuộc về sư phạm | pedagogical theory | pedagogical approach, pedagogical methods |

| multidimensional | adj | /ˌmʌltɪdaɪˈmenʃənl/ | đa chiều | multidimensional challenges | multidimensional problem, multidimensional analysis |

| transformative | adj | /trænsˈfɔːmətɪv/ | mang tính biến đổi | transformative learning | transformative experience, transformative change |

| constructivist | adj | /kənˈstrʌktɪvɪst/ | theo thuyết kiến tạo | constructivist learning theories | constructivist approach, constructivist teaching |

| marginalized | adj | /ˈmɑːdʒɪnəlaɪzd/ | bị gạt ra ngoài lề | marginalized communities | marginalized groups, marginalized populations |

| perpetuate | v | /pəˈpetʃueɪt/ | duy trì, làm lâu dài | perpetuate unsustainable practices | perpetuate inequality, perpetuate problems |

| socioeconomic | adj | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk/ | kinh tế – xã hội | socioeconomic contexts | socioeconomic status, socioeconomic factors |

| circular economy | n | /ˈsɜːkjələr iˈkɒnəmi/ | nền kinh tế tuần hoàn | promote circular economy | circular economy principles, circular economy model |

| biodiversity | n | /ˌbaɪəʊdaɪˈvɜːsəti/ | đa dạng sinh học | biodiversity conservation | biodiversity loss, protect biodiversity |

| stewardship | n | /ˈstjuːədʃɪp/ | trách nhiệm quản lý | environmental stewardship | environmental stewardship, practice stewardship |

| indigenous | adj | /ɪnˈdɪdʒənəs/ | bản địa | indigenous communities | indigenous knowledge, indigenous peoples |

| interdisciplinary | adj | /ˌɪntədɪsəˈplɪnəri/ | liên ngành | interdisciplinary research | interdisciplinary approach, interdisciplinary collaboration |

| institutional inertia | n | /ˌɪnstɪˈtjuːʃənl ɪˈnɜːʃə/ | quán tính thể chế | suffer from institutional inertia | overcome institutional inertia |

| disciplinary silos | n | /ˈdɪsəplɪnəri ˈsaɪləʊz/ | sự tách biệt theo ngành | structured around disciplinary silos | break down disciplinary silos |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| neurocognitive | adj | /ˌnjʊərəʊˈkɒɡnətɪv/ | thần kinh-nhận thức | neurocognitive dimensions | neurocognitive processes, neurocognitive functions |

| neurobiological | adj | /ˌnjʊərəʊˌbaɪəˈlɒdʒɪkl/ | thần kinh sinh học | neurobiological mechanisms | neurobiological basis, neurobiological research |

| affective | adj | /əˈfektɪv/ | liên quan đến cảm xúc | affective connections | affective neuroscience, affective responses |

| neuroplasticity | n | /ˌnjʊərəʊplæˈstɪsəti/ | tính dẻo thần kinh | brain neuroplasticity | neuroplasticity research, promote neuroplasticity |

| fMRI | n | /ef em ɑːr aɪ/ | chụp cộng hưởng từ chức năng | using fMRI | fMRI studies, fMRI research |

| limbic system | n | /ˈlɪmbɪk ˈsɪstəm/ | hệ limbic | role of limbic system | limbic system activation |

| amygdala | n | /əˈmɪɡdələ/ | hạch hạnh nhân | amygdala responds | amygdala activation, amygdala function |

| hippocampus | n | /ˌhɪpəˈkæmpəs/ | hồi hải mã | amygdala-hippocampal interactions | hippocampus function |

| prefrontal cortex | n | /ˌpriːˈfrʌntl ˈkɔːteks/ | vỏ não trước trán | prefrontal cortex plays role | prefrontal cortex activation |

| executive functions | n | /ɪɡˈzekjətɪv ˈfʌŋkʃnz/ | chức năng điều hành | orchestrates executive functions | executive functions include |

| contemplative | adj | /kənˈtemplətɪv/ | thiền định | contemplative neuroscience | contemplative practice, contemplative approach |

| default mode network | n | /dɪˈfɔːlt məʊd ˈnetwɜːk/ | mạng trạng thái mặc định | activity in default mode network | default mode network activity |

| anthropocentric | adj | /ˌænθrəpəʊˈsentrɪk/ | lấy con người làm trung tâm | from anthropocentric worldview | anthropocentric view, anthropocentric perspective |

| ecocentric | adj | /ˌiːkəʊˈsentrɪk/ | lấy sinh thái làm trung tâm | to ecocentric worldview | ecocentric perspective, ecocentric ethics |

| mirror neuron | n | /ˈmɪrə ˈnjʊərɒn/ | nơ-ron gương | mirror neuron systems | mirror neuron activation, mirror neuron research |

| dopamine | n | /ˈdəʊpəmiːn/ | dopamine (chất dẫn truyền thần kinh) | releasing dopamine | dopamine release, dopamine system |

| temporal discounting | n | /ˈtempərəl dɪsˈkaʊntɪŋ/ | chiết khấu thời gian | temporal discounting reflects | reduce temporal discounting |

| cognitive dissonance | n | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv ˈdɪsənəns/ | bất hòa nhận thức | cognitive dissonance reflects | experience cognitive dissonance |

| self-efficacy | n | /self ˈefɪkəsi/ | tự tin vào khả năng bản thân | neuroscience of self-efficacy | build self-efficacy, enhance self-efficacy |

Kết bài

Chủ đề “The role of education in promoting sustainable practices” không chỉ là một chủ đề phổ biến trong IELTS Reading mà còn phản ánh một trong những thách thức cấp bách nhất của thế kỷ 21. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được trải nghiệm đầy đủ cấu trúc của một bài thi IELTS Reading thực tế với ba passages có độ khó tăng dần.

Passage 1 giới thiệu các khái niệm cơ bản về giáo dục bền vững với ngôn ngữ dễ tiếp cận, Passage 2 đào sâu vào các khía cạnh lý thuyết và thực tiễn với từ vựng học thuật phong phú hơn, và Passage 3 thách thức bạn với nội dung chuyên sâu về khoa học thần kinh và tâm lý học nhận thức – thể hiện đúng độ khó của đề thi IELTS thực tế.

Với 40 câu hỏi đa dạng, bạn đã thực hành hầu hết các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến trong IELTS Reading. Phần đáp án chi tiết không chỉ cung cấp câu trả lời đúng mà còn giải thích cách xác định thông tin, paraphrase và chiến lược làm bài – những kỹ năng thiết yếu để đạt band điểm cao.

Hơn 100 từ vựng được phân tích kỹ lưỡng sẽ giúp bạn xây dựng vốn từ học thuật, không chỉ cho phần Reading mà còn cho cả Writing và Speaking. Hãy ôn tập những từ này thường xuyên và chú ý cách chúng được sử dụng trong ngữ cảnh.

Để tận dụng tối đa đề thi này, hãy làm lại nhiều lần với các chiến lược khác nhau, phân tích kỹ những câu sai và học thuộc từ vựng trong bảng. Chúc bạn học tốt và đạt được band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!

[…] The role of education in promoting sustainable practices cũng cần xem xét đến sự đa dạng về văn hóa khi thiết kế các chương trình giáo dục toàn cầu. […]