Mở Bài

Chủ đề năng lượng tái tạo và nghèo năng lượng là một trong những chủ đề xã hội-môi trường quan trọng thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS Reading. Với xu hướng phát triển bền vững và chuyển đổi năng lượng trên toàn cầu, các bài đọc về vai trò của năng lượng tái tạo trong việc cải thiện chất lượng cuộc sống cho cộng đồng nghèo đã trở thành một dạng đề phổ biến trong các kỳ thi IELTS gần đây.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages theo đúng chuẩn thi thật, từ độ khó Easy đến Hard. Bạn sẽ được thực hành với đầy đủ các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến như Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và nhiều dạng khác. Mỗi câu hỏi đều có đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin trong bài và kỹ thuật paraphrase, giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách tiếp cận đúng đắn.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, với nội dung được thiết kế bài bản để giúp bạn làm quen với cấu trúc đề thi thực tế, nâng cao vốn từ vựng chuyên ngành và rèn luyện kỹ năng đọc hiểu học thuật một cách hiệu quả nhất.

1. Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính 1 điểm, và tổng điểm sẽ được quy đổi thành band score từ 1-9.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1 (Easy): 15-17 phút – Đây là passage dễ nhất, bạn cần hoàn thành nhanh để dành thời gian cho các passage khó hơn

- Passage 2 (Medium): 18-20 phút – Độ khó trung bình, yêu cầu đọc kỹ và paraphrase tốt

- Passage 3 (Hard): 23-25 phút – Passage khó nhất với từ vựng học thuật và cấu trúc câu phức tạp

Lưu ý quan trọng: Không có thời gian phụ để chép đáp án sang answer sheet, vì vậy bạn cần ghi đáp án trực tiếp trong khi làm bài.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm đầy đủ các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Chọn đáp án đúng từ các lựa chọn A, B, C, D

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hay không được đề cập

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề phù hợp với từng đoạn văn

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào chỗ trống trong đoạn tóm tắt

- Matching Features – Nối thông tin với các đối tượng tương ứng

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn bằng từ trong bài

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Bringing Light to Rural Communities

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

For billions of people around the world, access to reliable electricity remains a distant dream. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, more than 600 million people live without electricity, relying instead on kerosene lamps, candles, and wood fires for light and cooking. This phenomenon, known as energy poverty, has profound effects on health, education, and economic development. However, the rapid advancement of renewable energy technologies is beginning to transform this landscape, offering hope to communities that have been left in darkness for generations.

Solar power has emerged as the most promising solution for addressing energy poverty in remote areas. Unlike traditional electricity grids, which require massive infrastructure investments and years of construction, solar panels can be installed quickly and at a fraction of the cost. A typical solar home system, consisting of a small panel, a battery, and LED lights, can be set up in a single day and provides enough electricity to power lights, charge mobile phones, and run small appliances. These systems cost between $100 and $300, which, while still expensive for many rural families, is far more affordable than extending the national grid to remote villages.

The impact of these solar systems on daily life has been remarkable. Children can now study after dark, extending their learning time by several hours each day. Health clinics can refrigerate vaccines and operate medical equipment, dramatically improving healthcare outcomes in rural areas. Small businesses can operate longer hours, and entrepreneurs can charge neighbors’ phones for a small fee, creating new income-generating opportunities. In Kenya, for example, the M-KOPA Solar company has connected more than one million homes to solar power since 2012, using an innovative pay-as-you-go model that allows families to purchase systems through small daily payments via mobile money.

Wind energy is also playing a crucial role in bringing electricity to underserved communities, particularly in areas with consistent wind patterns. Small-scale wind turbines, ranging from 400 watts to 20 kilowatts, can power individual homes, farms, or small communities. In Inner Mongolia, China, small wind turbines have been providing electricity to herder families living in isolated areas for decades. These turbines are particularly valuable because they can generate power day and night, complementing solar systems that only work during daylight hours. The combination of wind and solar power, known as hybrid systems, offers the most reliable solution for off-grid communities.

Micro-hydropower systems represent another effective renewable energy solution for mountainous regions with flowing water. These systems, which can range from a few hundred watts to 100 kilowatts, harness the energy of small streams and rivers to generate electricity. Unlike large dams, micro-hydropower installations have minimal environmental impact and can be built and maintained by local communities. In Nepal, more than 3,000 micro-hydropower systems have been installed, providing electricity to remote mountain villages that would otherwise remain disconnected from modern energy sources. The technology is simple enough that local technicians can handle maintenance, ensuring long-term sustainability.

The economic benefits of renewable energy access extend far beyond household lighting. When communities gain access to electricity, they can attract new businesses, improve agricultural productivity through electric pumps and processing equipment, and connect to the global economy through internet access. Studies have shown that villages with electricity experience faster economic growth, higher incomes, and improved gender equality as women are freed from time-consuming tasks like collecting firewood. In Bangladesh, the Grameen Shakti program has installed more than 1.5 million solar home systems, creating thousands of jobs in installation, maintenance, and manufacturing while simultaneously addressing energy poverty.

Despite these successes, significant challenges remain. The upfront cost of renewable energy systems, even with financing options, remains prohibitive for the poorest families. Many rural areas lack the technical expertise needed to maintain these systems, leading to breakdowns and abandonment. Government policies and regulations often fail to support off-grid renewable energy, focusing instead on large-scale grid expansion that may take decades to reach remote communities. Additionally, while solar panels and batteries have become much cheaper in recent years, the cost of quality components and professional installation can still be high.

Looking ahead, experts predict that renewable energy will continue to be the primary solution for eliminating energy poverty. Technological improvements are making systems more efficient and affordable, while innovative financing models are removing barriers to access. International organizations, governments, and private companies are increasingly recognizing that distributed renewable energy – rather than grid extension – offers the fastest and most cost-effective path to universal energy access. For millions of people living in darkness, renewable energy is not just about electricity; it represents hope, opportunity, and a pathway out of poverty.

Questions 1-6

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- More than half a billion people in sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to electricity.

- Solar home systems are cheaper to install than connecting remote villages to the national electricity grid.

- M-KOPA Solar has been operating in Kenya since before 2010.

- Wind turbines can only generate electricity during the daytime.

- Micro-hydropower systems cause significant damage to the environment.

- Women in villages with electricity have more free time because they no longer need to collect firewood.

Questions 7-10

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Renewable energy technologies are helping to address energy poverty in developing countries. Solar panels are particularly useful because they can be installed quickly without requiring expensive 7. __ like traditional electricity grids. A typical solar system includes panels, batteries, and 8. __ and costs between $100 and $300. In Kenya, companies use a 9. __ model that allows families to make small daily payments. For areas with consistent wind, 10. __ combining solar and wind power offer the most reliable electricity supply.

Questions 11-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, which of the following is NOT mentioned as a benefit of solar home systems?

- A. Children can study for longer hours

- B. Medical facilities can store vaccines

- C. Businesses can operate after dark

- D. Families can heat their homes in winter

- The passage suggests that micro-hydropower systems in Nepal are sustainable because:

- A. They are built by international organizations

- B. Local technicians can perform maintenance work

- C. They generate more power than solar systems

- D. The government provides ongoing financial support

- What does the passage indicate about the future of energy poverty?

- A. It will be eliminated primarily through grid expansion

- B. It will remain a problem due to high costs

- C. It will be addressed mainly through renewable energy

- D. It will require new technological inventions

PASSAGE 2 – The Economics of Energy Access

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The relationship between energy access and economic development has been well established in academic literature, yet the precise mechanisms through which renewable energy alleviates poverty remain subjects of ongoing research and debate. While the immediate benefits of electrification—improved lighting, communication capabilities, and access to information—are readily apparent, the downstream economic effects are more complex and context-dependent. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers and development organizations seeking to maximize the poverty reduction potential of renewable energy interventions.

A Traditional economic models of development have emphasized the importance of large-scale infrastructure investments, particularly in centralized electricity generation and transmission networks. This approach, sometimes called the “grid extension paradigm,” assumes that connecting communities to national electricity grids represents the most efficient path to universal energy access. However, empirical evidence from recent decades has challenged this assumption, particularly in the context of sparsely populated rural areas where the cost per connection can exceed $5,000 per household. In such settings, decentralized renewable energy systems have emerged as economically superior alternatives, offering faster deployment times, lower capital requirements, and greater resilience to system-wide failures.

B The economic case for renewable energy in addressing energy poverty rests on several pillars. First, the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) from solar photovoltaic systems has declined by more than 90% since 2010, making solar power competitive with or cheaper than diesel generators in most markets. This dramatic cost reduction has been driven by technological innovations, economies of scale in manufacturing, and increased competition among suppliers. Second, renewable energy systems eliminate or significantly reduce fuel costs, which often represent the largest ongoing expense for diesel-based mini-grids. For remote communities previously dependent on expensive kerosene or diesel, the savings can be substantial—studies in East Africa have documented household energy expenditure reductions of 60-80% following solar adoption.

C However, the poverty reduction impact of energy access depends critically on how that energy is utilized. Researchers distinguish between household electricity consumption and productive uses of energy—applications that generate income or enhance productivity. While household electricity provides important welfare benefits, its direct contribution to poverty reduction is limited. In contrast, productive uses—such as powering irrigation pumps, processing equipment, or commercial refrigeration—can create transformative economic opportunities. A study of rural electrification in India found that villages where electricity was used primarily for productive purposes experienced income growth rates three times higher than villages where consumption was predominantly residential.

D This finding has important implications for the design of energy access programs. Many early renewable energy initiatives focused solely on providing basic household electricity, typically enough to power a few lights and charge mobile phones. While valuable, these minimalist approaches often failed to catalyze broader economic development. Newer programs increasingly emphasize productive use promotion, combining energy access with complementary interventions such as agricultural extension services, business training, and access to credit. The Power Africa initiative, for instance, not only supports renewable energy deployment but also works to develop local markets for energy-intensive products and services.

E The gender dimensions of energy poverty and renewable energy access have received growing attention from researchers and practitioners. Women and girls typically bear the greatest burden of energy poverty, spending hours each day collecting firewood or biomass for cooking and heating. This time poverty restricts educational and income-generating opportunities, perpetuating cycles of gender inequality. Several studies have documented that renewable energy access can significantly reduce women’s domestic work burden, allowing them to pursue education or start businesses. Moreover, the renewable energy sector itself has shown potential for female entrepreneurship, with women comprising a substantial portion of solar equipment sales agents and service technicians in countries like Bangladesh and Tanzania.

F Despite these promising developments, the relationship between renewable energy and poverty reduction is neither automatic nor universal. Several factors mediate outcomes, including the reliability and affordability of energy services, the presence of complementary infrastructure (such as roads and telecommunications), local governance capacity, and broader economic conditions. A renewable energy system that frequently breaks down or requires expensive replacement parts delivers little benefit. Similarly, energy access alone cannot overcome fundamental barriers to economic opportunity, such as limited market access, lack of education, or discriminatory social norms.

G Financial sustainability represents another critical challenge for renewable energy interventions targeting poor communities. While the declining costs of solar panels and other equipment have improved project economics, ensuring long-term operational sustainability remains difficult. Many off-grid renewable energy systems rely on ongoing subsidies or cross-subsidization from wealthier customers. The cost recovery dilemma is particularly acute for systems serving the poorest households, who may struggle to afford even heavily subsidized tariffs. Some innovative programs have addressed this through tiered pricing structures, where wealthier customers pay higher rates that subsidize service for poorer neighbors, though such models raise questions about economic efficiency and scalability.

The evidence accumulated over the past two decades demonstrates that renewable energy can serve as a powerful tool for poverty reduction when deployed strategically. However, success requires more than simply installing solar panels or wind turbines. Effective programs must consider local economic conditions, promote productive uses of energy, ensure technical and financial sustainability, and address gender and social equity dimensions. As the global community works toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7—ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all—renewable energy will undoubtedly play a central role, but realizing its full potential demands careful attention to implementation details and local contexts.

Questions 14-19

The passage has seven paragraphs, A-G.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-G.

NB: You may use any letter more than once.

- A reference to the importance of additional support services beyond just providing electricity

- Discussion of how dramatically the cost of solar energy has fallen

- An explanation of why connecting remote areas to national grids may not be economical

- Information about how energy poverty particularly affects women

- A mention of the challenges in maintaining long-term operation of renewable energy systems

- Evidence showing that income growth depends on how electricity is used

Questions 20-23

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

- The cost of connecting a single household to the electricity grid in rural areas can be more than __ dollars.

- After adopting solar energy, households in East Africa reduced their energy spending by __ percent.

- A study in India showed that villages using electricity for productive purposes had income growth __ times higher than those using it mainly for homes.

- Achieving __ is identified as the global goal for universal access to sustainable energy.

Questions 24-26

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to paragraph B, the main reason solar power has become more affordable is:

- A. Government subsidies for poor communities

- B. Improved technology and increased manufacturing scale

- C. Competition from diesel generators

- D. International development funding

- The passage suggests that “minimalist approaches” to energy access:

- A. Are the most cost-effective solution

- B. Should be completely abandoned

- C. Did not lead to significant economic growth

- D. Are preferred by rural communities

- The author’s main argument about renewable energy and poverty reduction is that:

- A. It automatically leads to economic development

- B. It is less effective than grid extension

- C. It requires careful implementation to succeed

- D. It is too expensive for developing countries

PASSAGE 3 – Policy Frameworks and Systemic Transformation

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The challenge of eradicating energy poverty through renewable energy deployment transcends purely technical or economic considerations, entering the complex realm of policy architecture, institutional capacity, and socio-political dynamics. While the declining costs of renewable energy technologies have created unprecedented opportunities for expanding energy access, translating these technical possibilities into widespread implementation requires sophisticated policy frameworks that navigate competing interests, overcome path dependencies in existing energy systems, and mobilize financial resources at scale. The experiences of countries that have made significant progress in addressing energy poverty through renewable energy reveal both the critical importance of enabling policy environments and the persistent challenges that emerge when attempting systemic transformations of energy systems.

At the core of effective policy frameworks for renewable energy-based poverty alleviation lies the challenge of regulatory design. Traditional utility regulation, developed primarily for large-scale, centralized power generation and distribution, proves ill-suited to the decentralized, modular nature of renewable energy systems serving off-grid or underserved populations. Regulatory frameworks optimized for conventional utilities typically emphasize economies of scale, centralized planning, and rate-of-return regulation—approaches that inadvertently create barriers to distributed renewable energy deployment. For instance, licensing requirements designed for multi-megawatt power plants become unnecessarily burdensome for small-scale solar mini-grids serving a few hundred households. Similarly, technical standards developed for grid-connected systems may be inappropriate for off-grid applications, imposing compliance costs that undermine project viability.

Progressive policy frameworks have sought to address these regulatory mismatches through various mechanisms. Several countries have established separate regulatory categories for mini-grids and stand-alone systems, with simplified licensing procedures and tailored technical standards. Bangladesh’s Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL), for example, operates under a streamlined regulatory framework that has facilitated the installation of millions of solar home systems without requiring individual project approvals. Kenya has implemented a tiered licensing system where small renewable energy projects below certain capacity thresholds face minimal regulatory requirements, while larger installations undergo more comprehensive review processes. These adaptive regulatory approaches recognize that effective oversight need not require uniformly stringent regulation across all scales and technologies.

The financing architecture for renewable energy projects targeting energy-poor populations presents distinct challenges that conventional project finance mechanisms struggle to address. The customer base—by definition composed of low-income households and enterprises—exhibits limited creditworthiness by traditional metrics, creating perceived risks that inflate financing costs or prevent capital deployment entirely. Moreover, the relatively small scale of individual projects generates high transaction costs relative to project value, making them unattractive to commercial lenders seeking efficient capital deployment. This financing gap has necessitated innovative institutional arrangements combining public subsidies, concessional finance, credit enhancements, and risk-sharing mechanisms to catalyze private sector participation.

Multilateral development banks and bilateral development agencies have experimented with various financing structures to address these challenges. Results-based financing, where payments are contingent upon verified outcomes (such as actual connections or generation capacity), has gained traction as a mechanism that incentivizes performance while allowing implementers flexibility in approach. The World Bank’s Lighting Global program employs a market transformation approach, using concessional finance and technical assistance to build supply chains and reduce market barriers rather than directly subsidizing end-user purchases. Some initiatives have established dedicated financing facilities that aggregate small projects into larger portfolios, reducing transaction costs and enabling access to institutional capital markets. The Green Climate Fund has begun supporting such facility-based approaches, recognizing that addressing energy poverty at scale requires financial architecture tailored to the specific characteristics of this market segment.

Beyond regulatory and financial considerations, successful policy frameworks must address the institutional ecosystem surrounding renewable energy deployment. Many countries suffering from acute energy poverty simultaneously face institutional fragmentation, with responsibilities for energy access scattered across multiple ministries, agencies, and levels of government. This fragmentation generates coordination challenges, policy inconsistencies, and gaps in implementation capacity. For instance, while a national energy ministry might set renewable energy targets, local governments often control land-use planning and business licensing—creating potential regulatory conflicts that impede project development. Similarly, rural electrification agencies, utilities, and environmental authorities may operate under conflicting mandates that complicate renewable energy project approval and implementation.

Some countries have addressed institutional fragmentation through creation of dedicated agencies with clear mandates for expanding energy access through renewable resources. Ethiopia’s Rural Electrification Agency serves as a one-stop-shop for off-grid renewable energy projects, coordinating across relevant government entities and providing streamlined approval processes. Rwanda has established an Energy Access Task Force within the Prime Minister’s office, providing high-level political backing and cross-ministerial coordination for energy access initiatives. These institutional innovations reflect recognition that policy frameworks exist not merely as abstract rules but as implementations of institutional capabilities and organizational relationships.

The political economy of energy transitions further complicates policy development for renewable energy-based poverty alleviation. Existing energy systems generate powerful vested interests—utilities, fossil fuel producers, equipment suppliers, and the workforce employed in these sectors—that may view distributed renewable energy as threatening to established business models and employment patterns. Even where renewable energy offers superior economics for expanding access to underserved populations, political resistance from incumbent interests can obstruct policy reform. The subsidy dependency of many conventional utilities, particularly in developing countries where electricity tariffs often fail to cover costs, creates fiscal obligations that governments find difficult to abandon despite their questionable effectiveness in addressing energy poverty.

Navigating these political economy challenges requires building coalitions for reform that extend beyond traditional energy sector stakeholders. Successful policy reforms have often emerged when energy access became linked to broader development priorities commanding wider political support—such as agricultural productivity, healthcare delivery, or education outcomes. The framing of renewable energy not merely as an alternative electricity source but as an enabler of rural development can shift political dynamics, attracting support from ministries and constituencies beyond the energy sector. Similarly, demonstrating that renewable energy deployment creates local employment opportunities—in installation, maintenance, sales, and manufacturing—can help overcome resistance from those concerned about energy transition impacts on livelihoods.

The trajectory of policy development in this domain suggests that effective frameworks require adaptive management—ongoing learning, experimentation, and refinement based on implementation experience. Many successful approaches emerged not from comprehensive master plans but from iterative processes of policy experimentation, evaluation, and adjustment. This underscores the importance of building monitoring and evaluation capacities that generate evidence about what works, under what circumstances, and why. It also highlights the value of policy environments that encourage innovation and tolerate calculated risks, recognizing that addressing the complex challenge of energy poverty through renewable energy requires exploring multiple pathways rather than betting on singular solutions.

As the global community confronts the dual imperatives of achieving universal energy access and transitioning to sustainable energy systems, the role of policy frameworks in enabling renewable energy to address energy poverty will only intensify. The technical and economic foundations for this transition have strengthened dramatically, but realizing the potential of renewable energy to transform the lives of billions living in energy poverty depends fundamentally on constructing policy environments that facilitate rather than frustrate implementation. The challenge facing policymakers is not whether renewable energy can address energy poverty—the evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates it can—but whether they can muster the political will and institutional creativity necessary to remove the barriers that too often prevent promising solutions from reaching those who need them most.

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, traditional utility regulation is unsuitable for renewable energy systems because:

- A. It was designed for large, centralized power systems

- B. It is too expensive to implement

- C. It does not consider environmental impacts

- D. It favors fossil fuel companies

- The passage describes Bangladesh’s IDCOL as an example of:

- A. A failed regulatory experiment

- B. A streamlined regulatory approach

- C. An international development agency

- D. A private sector initiative

- What does the author identify as a key problem with financing renewable energy projects for poor communities?

- A. Renewable energy is more expensive than fossil fuels

- B. Poor households cannot use electricity productively

- C. Small project sizes lead to high transaction costs

- D. International banks refuse to invest in developing countries

- The passage suggests that institutional fragmentation in government:

- A. Helps coordinate renewable energy projects

- B. Creates obstacles for project implementation

- C. Is necessary for effective governance

- D. Only occurs in wealthy countries

- According to the passage, political resistance to renewable energy can be reduced by:

- A. Eliminating all fossil fuel subsidies immediately

- B. Connecting energy access to broader development goals

- C. Ignoring concerns about employment impacts

- D. Focusing exclusively on urban electrification

Questions 32-36

Complete the summary using the list of phrases, A-J, below.

Effective policy frameworks for renewable energy must address multiple challenges. Regulatory systems need to be 32. __ to accommodate the unique characteristics of decentralized renewable energy. Financing mechanisms must overcome 33. __ and high transaction costs through innovative structures like results-based financing. Governments must address 34. __ by creating dedicated agencies with clear mandates. The political economy challenge requires building 35. __ that extend beyond traditional energy sector interests. Finally, successful policies require 36. __ that allows for ongoing learning and adjustment.

A. institutional fragmentation

B. adaptive management

C. economic efficiency

D. modified or redesigned

E. limited creditworthiness

F. political coalitions

G. environmental standards

H. international cooperation

I. technical training

J. centralized control

Questions 37-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- The declining cost of renewable energy technology alone is sufficient to eliminate energy poverty.

- Small-scale renewable energy projects require the same regulatory oversight as large power plants.

- Results-based financing has proven effective in encouraging project performance.

- Most successful energy access policies were developed through trial-and-error rather than comprehensive planning.

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- TRUE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- infrastructure

- LED lights

- pay-as-you-go

- hybrid systems

- D

- B

- C

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- D

- B

- A

- E

- G

- C

- 5,000 / five thousand

- 60-80

- three

- Sustainable Development Goal 7

- B

- C

- C

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- A

- B

- C

- B

- B

- D

- E

- A

- F

- B

- NO

- NO

- YES

- YES

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: more than half a billion, sub-Saharan Africa, no access to electricity

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài văn nói “more than 600 million people live without electricity” ở sub-Saharan Africa. 600 triệu lớn hơn nửa tỷ (500 triệu), vì vậy câu phát biểu đúng.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: solar home systems, cheaper, national electricity grid

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-6

- Giải thích: Bài văn khẳng định rõ ràng rằng solar home systems “can be set up in a single day and provides enough electricity… at a fraction of the cost” so với việc mở rộng lưới điện quốc gia. “Fraction of the cost” có nghĩa là rẻ hơn nhiều.

Câu 3: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: M-KOPA Solar, Kenya, before 2010

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: Bài văn nói M-KOPA Solar “has connected more than one million homes to solar power since 2012”, nghĩa là công ty bắt đầu hoạt động từ năm 2012, không phải trước 2010.

Câu 4: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: wind turbines, only generate electricity, daytime

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: Bài văn nói rõ turbines “can generate power day and night”, mâu thuẫn trực tiếp với câu phát biểu rằng chúng chỉ hoạt động ban ngày.

Câu 5: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: micro-hydropower systems, significant damage, environment

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài văn nói micro-hydropower có “minimal environmental impact” (tác động môi trường tối thiểu), ngược lại với việc gây thiệt hại đáng kể.

Câu 6: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: women, villages with electricity, more free time, collecting firewood

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: Bài văn nói villages with electricity experience “improved gender equality as women are freed from time-consuming tasks like collecting firewood”, xác nhận phụ nữ có nhiều thời gian rảnh hơn.

Câu 7: infrastructure

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: expensive, traditional electricity grids

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: Bài văn nói “Unlike traditional electricity grids, which require massive infrastructure investments”. Từ cần điền là “infrastructure”.

Câu 8: LED lights

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: solar system includes, panels, batteries

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: Bài văn liệt kê components: “a small panel, a battery, and LED lights”.

Câu 9: pay-as-you-go

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: Kenya, companies use, small daily payments

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: M-KOPA Solar “using an innovative pay-as-you-go model that allows families to purchase systems through small daily payments”.

Câu 10: hybrid systems

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: combining solar and wind power, reliable electricity supply

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 6-7

- Giải thích: “The combination of wind and solar power, known as hybrid systems, offers the most reliable solution”.

Câu 11: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Giải thích: Đoạn 3 đề cập children studying (A), health clinics refrigerating vaccines (B), và businesses operating longer hours (C). Tuy nhiên, việc sưởi ấm nhà cửa vào mùa đông (D) không được đề cập đến.

Câu 12: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “The technology is simple enough that local technicians can handle maintenance, ensuring long-term sustainability.”

Câu 13: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Experts predict that renewable energy will continue to be the primary solution for eliminating energy poverty.”

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: D

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Thông tin: Additional support services beyond electricity

- Giải thích: Paragraph D discusses “productive use promotion, combining energy access with complementary interventions such as agricultural extension services, business training, and access to credit.”

Câu 15: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Thông tin: Dramatic fall in solar energy cost

- Giải thích: Paragraph B states “The levelized cost of electricity from solar photovoltaic systems has declined by more than 90% since 2010.”

Câu 16: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Thông tin: Why connecting remote areas to grids is not economical

- Giải thích: Paragraph A explains “the cost per connection can exceed $5,000 per household” for grid extension to sparsely populated rural areas.

Câu 17: E

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Thông tin: How energy poverty affects women

- Giải thích: Paragraph E discusses how “Women and girls typically bear the greatest burden of energy poverty, spending hours each day collecting firewood.”

Câu 18: G

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Thông tin: Challenges in long-term operation

- Giải thích: Paragraph G addresses “ensuring long-term operational sustainability remains difficult” and discusses financial sustainability challenges.

Câu 19: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Information

- Thông tin: Income growth depends on how electricity is used

- Giải thích: Paragraph C presents “A study of rural electrification in India found that villages where electricity was used primarily for productive purposes experienced income growth rates three times higher.”

Câu 20: 5,000 / five thousand

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph A

- Giải thích: “The cost per connection can exceed $5,000 per household.”

Câu 21: 60-80

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph B

- Giải thích: “Studies in East Africa have documented household energy expenditure reductions of 60-80% following solar adoption.”

Câu 22: three

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph C

- Giải thích: “Villages where electricity was used primarily for productive purposes experienced income growth rates three times higher.”

Câu 23: Sustainable Development Goal 7

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn cuối

- Giải thích: “As the global community works toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7—ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all.”

Câu 24: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph B

- Giải thích: “This dramatic cost reduction has been driven by technological innovations, economies of scale in manufacturing, and increased competition among suppliers.”

Câu 25: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Paragraph D

- Giải thích: “These minimalist approaches often failed to catalyze broader economic development,” meaning they did not lead to significant economic growth.

Câu 26: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Giải thích: Throughout the passage, the author emphasizes that success “requires more than simply installing solar panels” and demands “careful attention to implementation details and local contexts.”

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: A

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Traditional utility regulation, developed primarily for large-scale, centralized power generation and distribution, proves ill-suited to the decentralized, modular nature of renewable energy systems.”

Câu 28: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “Bangladesh’s Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL), for example, operates under a streamlined regulatory framework.”

Câu 29: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “Moreover, the relatively small scale of individual projects generates high transaction costs relative to project value.”

Câu 30: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “This fragmentation generates coordination challenges, policy inconsistencies, and gaps in implementation capacity.”

Câu 31: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Successful policy reforms have often emerged when energy access became linked to broader development priorities commanding wider political support.”

Câu 32: D (modified or redesigned)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Giải thích: Regulatory systems need to be adapted/modified to suit decentralized renewable energy, as discussed in paragraphs 2-3.

Câu 33: E (limited creditworthiness)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4

- Giải thích: “The customer base… exhibits limited creditworthiness by traditional metrics.”

Câu 34: A (institutional fragmentation)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6

- Giải thích: Governments must address “institutional fragmentation” through dedicated agencies.

Câu 35: F (political coalitions)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9

- Giải thích: Success requires “building coalitions for reform that extend beyond traditional energy sector stakeholders.”

Câu 36: B (adaptive management)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: “Effective frameworks require adaptive management—ongoing learning, experimentation, and refinement.”

Câu 37: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1

- Giải thích: The author states that addressing energy poverty “transcends purely technical or economic considerations,” meaning declining costs alone are not sufficient. This contradicts the statement.

Câu 38: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2-3

- Giải thích: The author argues that requiring the same oversight “become unnecessarily burdensome for small-scale” projects and discusses streamlined approaches.

Câu 39: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5

- Giải thích: “Results-based financing… has gained traction as a mechanism that incentivizes performance,” indicating the writer believes it has proven effective.

Câu 40: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 10

- Giải thích: “Many successful approaches emerged not from comprehensive master plans but from iterative processes of policy experimentation, evaluation, and adjustment.”

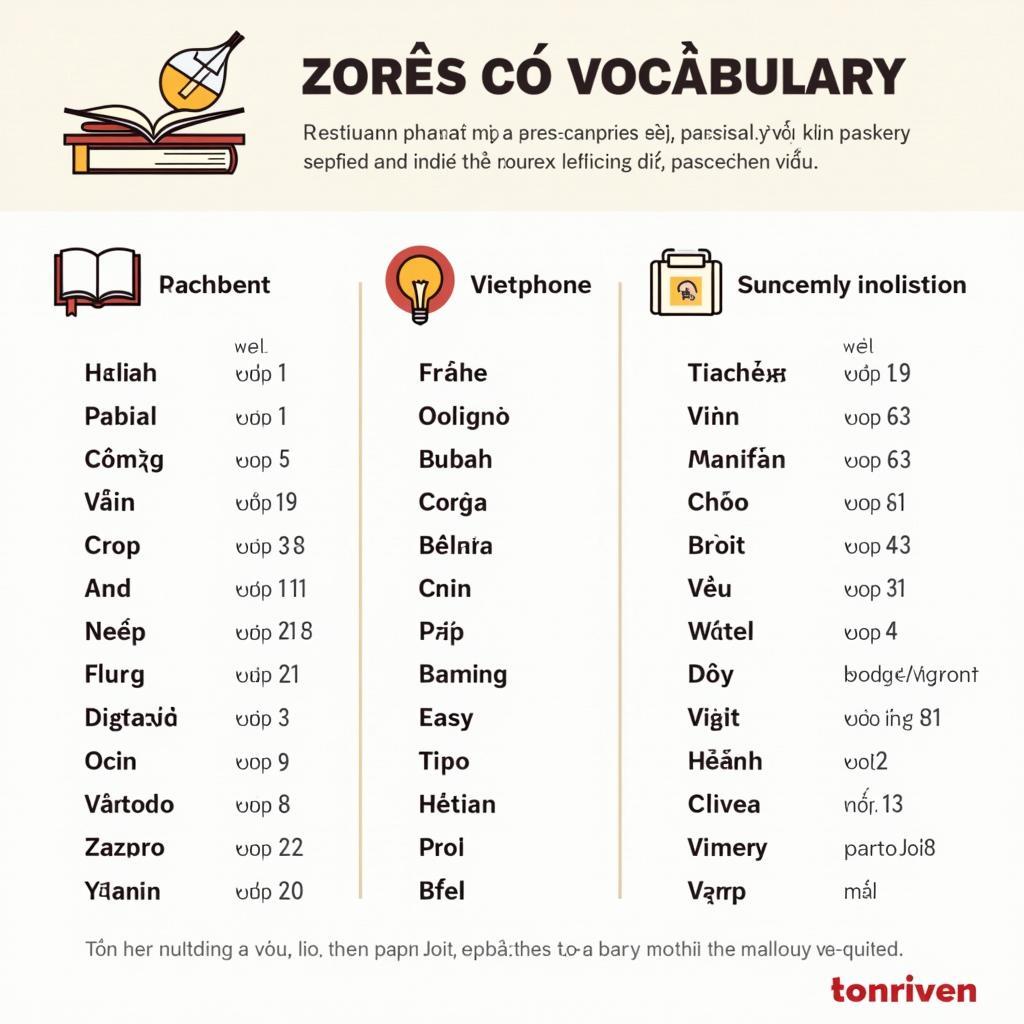

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| energy poverty | noun phrase | /ˈenədʒi ˈpɒvəti/ | nghèo năng lượng | This phenomenon, known as energy poverty, has profound effects | address/tackle energy poverty |

| renewable energy | noun phrase | /rɪˈnjuːəbl ˈenədʒi/ | năng lượng tái tạo | The rapid advancement of renewable energy technologies | renewable energy technologies/sources |

| solar panel | noun phrase | /ˈsəʊlə ˈpænl/ | tấm pin mặt trời | Solar panels can be installed quickly | install solar panels |

| kerosene lamp | noun phrase | /ˈkerəsiːn læmp/ | đèn dầu hỏa | Relying instead on kerosene lamps for light | replace kerosene lamps |

| remarkable | adjective | /rɪˈmɑːkəbl/ | đáng chú ý, đáng kinh ngạc | The impact of these solar systems has been remarkable | remarkable impact/achievement |

| pay-as-you-go | adjective | /peɪ əz juː ɡəʊ/ | trả tiền theo mức sử dụng | Using an innovative pay-as-you-go model | pay-as-you-go model/system |

| wind turbine | noun phrase | /wɪnd ˈtɜːbaɪn/ | tuabin gió | Small-scale wind turbines can power homes | install wind turbines |

| hybrid system | noun phrase | /ˈhaɪbrɪd ˈsɪstəm/ | hệ thống lai, hệ thống kết hợp | Hybrid systems offer the most reliable solution | solar-wind hybrid systems |

| micro-hydropower | noun phrase | /ˈmaɪkrəʊ ˈhaɪdrəʊpaʊə/ | thủy điện quy mô nhỏ | Micro-hydropower systems harness energy | micro-hydropower installation |

| minimal | adjective | /ˈmɪnɪməl/ | tối thiểu | These systems have minimal environmental impact | minimal impact/effect |

| income-generating | adjective | /ˈɪnkʌm ˈdʒenəreɪtɪŋ/ | tạo thu nhập | Creating new income-generating opportunities | income-generating activities/opportunities |

| upfront cost | noun phrase | /ˌʌpˈfrʌnt kɒst/ | chi phí ban đầu | The upfront cost remains prohibitive | high upfront cost |

| universal access | noun phrase | /ˌjuːnɪˈvɜːsl ˈækses/ | tiếp cận phổ quát | The fastest path to universal energy access | achieve universal access |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| downstream | adjective | /ˌdaʊnˈstriːm/ | gián tiếp, hậu quả sau này | The downstream economic effects are complex | downstream effects/impacts |

| context-dependent | adjective | /ˈkɒntekst dɪˈpendənt/ | phụ thuộc vào bối cảnh | The effects are context-dependent | highly context-dependent |

| paradigm | noun | /ˈpærədaɪm/ | mô hình, hệ thống tư duy | The grid extension paradigm | shift in paradigm |

| resilience | noun | /rɪˈzɪliəns/ | khả năng phục hồi, tính bền vững | Greater resilience to system-wide failures | build resilience |

| levelized cost | noun phrase | /ˈlevəlaɪzd kɒst/ | chi phí san phẳng (chi phí trung bình) | The levelized cost of electricity from solar | levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) |

| productive uses | noun phrase | /prəˈdʌktɪv ˈjuːsɪz/ | sử dụng sản xuất | Productive uses of energy generate income | promote productive uses |

| transformative | adjective | /trænsˈfɔːmətɪv/ | mang tính chuyển đổi | Can create transformative economic opportunities | transformative impact/change |

| minimalist | adjective | /ˈmɪnɪməlɪst/ | tối giản | These minimalist approaches often failed | minimalist approach/strategy |

| extension services | noun phrase | /ɪkˈstenʃn ˈsɜːvɪsɪz/ | dịch vụ khuyến nông | Complementary interventions such as extension services | agricultural extension services |

| time poverty | noun phrase | /taɪm ˈpɒvəti/ | nghèo thời gian | This time poverty restricts opportunities | suffer from time poverty |

| entrepreneurship | noun | /ˌɒntrəprəˈnɜːʃɪp/ | tinh thần khởi nghiệp | Potential for female entrepreneurship | promote entrepreneurship |

| cost recovery | noun phrase | /kɒst rɪˈkʌvəri/ | thu hồi chi phí | The cost recovery dilemma is acute | achieve cost recovery |

| tiered pricing | noun phrase | /tɪəd ˈpraɪsɪŋ/ | định giá theo bậc | Through tiered pricing structures | implement tiered pricing |

| scalability | noun | /ˌskeɪləˈbɪləti/ | khả năng mở rộng quy mô | Questions about scalability | improve scalability |

| subsidy | noun | /ˈsʌbsədi/ | trợ cấp | Systems rely on ongoing subsidies | government subsidy |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| policy architecture | noun phrase | /ˈpɒləsi ˈɑːkɪtektʃə/ | khung chính sách | The challenge enters the realm of policy architecture | design policy architecture |

| path dependencies | noun phrase | /pɑːθ dɪˈpendənsiz/ | sự phụ thuộc vào lộ trình đã đi | Overcome path dependencies in energy systems | historical path dependencies |

| regulatory design | noun phrase | /ˈreɡjələtəri dɪˈzaɪn/ | thiết kế quy định | The challenge of regulatory design | effective regulatory design |

| decentralized | adjective | /diːˈsentrəlaɪzd/ | phi tập trung | The decentralized nature of renewable systems | decentralized systems/approach |

| modular | adjective | /ˈmɒdjələ/ | theo mô-đun | The decentralized, modular nature | modular design/systems |

| rate-of-return | noun phrase | /reɪt əv rɪˈtɜːn/ | tỷ suất sinh lợi | Rate-of-return regulation | regulate rate-of-return |

| regulatory mismatch | noun phrase | /ˈreɡjələtəri ˈmɪsmætʃ/ | sự không phù hợp về quy định | Address these regulatory mismatches | identify regulatory mismatches |

| stand-alone system | noun phrase | /stænd əˈləʊn ˈsɪstəm/ | hệ thống độc lập | Separate categories for stand-alone systems | off-grid stand-alone systems |

| creditworthiness | noun | /ˈkredɪtwɜːðinəs/ | độ tín nhiệm | Limited creditworthiness by traditional metrics | assess creditworthiness |

| concessional finance | noun phrase | /kənˈseʃənl ˈfaɪnæns/ | tài chính ưu đãi | Combining public subsidies and concessional finance | provide concessional finance |

| risk-sharing | noun phrase | /rɪsk ˈʃeərɪŋ/ | chia sẻ rủi ro | Risk-sharing mechanisms to catalyze participation | risk-sharing arrangements |

| results-based financing | noun phrase | /rɪˈzʌlts beɪst ˈfaɪnænsɪŋ/ | tài chính dựa trên kết quả | Results-based financing has gained traction | implement results-based financing |

| market transformation | noun phrase | /ˈmɑːkɪt ˌtrænsfəˈmeɪʃn/ | chuyển đổi thị trường | Using a market transformation approach | drive market transformation |

| institutional fragmentation | noun phrase | /ˌɪnstɪˈtjuːʃənl ˌfræɡmenˈteɪʃn/ | sự phân mảnh thể chế | Countries face institutional fragmentation | overcome institutional fragmentation |

| regulatory conflict | noun phrase | /ˈreɡjələtəri ˈkɒnflɪkt/ | xung đột quy định | Creating potential regulatory conflicts | resolve regulatory conflicts |

| political economy | noun phrase | /pəˈlɪtɪkl iˈkɒnəmi/ | kinh tế chính trị | The political economy of energy transitions | understand political economy |

| vested interest | noun phrase | /ˈvestɪd ˈɪntrəst/ | lợi ích đã có | Generate powerful vested interests | protect vested interests |

| adaptive management | noun phrase | /əˈdæptɪv ˈmænɪdʒmənt/ | quản lý thích ứng | Effective frameworks require adaptive management | practice adaptive management |

| iterative process | noun phrase | /ˈɪtərətɪv ˈprəʊses/ | quy trình lặp lại | Emerged from iterative processes | follow an iterative process |

| political will | noun phrase | /pəˈlɪtɪkl wɪl/ | ý chí chính trị | Whether they can muster the political will | demonstrate political will |

Đề thi IELTS Reading về vai trò năng lượng tái tạo trong giảm nghèo năng lượng với ba passages đầy đủ

Đề thi IELTS Reading về vai trò năng lượng tái tạo trong giảm nghèo năng lượng với ba passages đầy đủ

Kết Bài

Chủ đề “The Role Of Renewable Energy In Reducing Energy Poverty” không chỉ là một vấn đề quan trọng trong thực tế mà còn là một chủ đề phổ biến trong các kỳ thi IELTS Reading. Bộ đề thi mẫu này đã cung cấp cho bạn trải nghiệm hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages được thiết kế tỉ mỉ theo đúng chuẩn bài thi thực tế, từ độ khó Easy phù hợp cho band 5.0-6.5, qua Medium cho band 6.0-7.5, và đến Hard cho band 7.0-9.0.

Tương tự như Impact of renewable energy on policy-making, đề thi này giúp bạn làm quen với cách IELTS đánh giá khả năng đọc hiểu học thuật của thí sinh. Qua 40 câu hỏi đa dạng bao gồm Multiple Choice, True/False/Not Given, Matching Headings, Summary Completion và nhiều dạng khác, bạn đã được rèn luyện toàn diện các kỹ năng cần thiết.

Đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin trong bài và kỹ thuật paraphrase sẽ giúp bạn hiểu rõ lý do tại sao một đáp án đúng và cách tiếp cận hiệu quả cho từng dạng câu hỏi. Đây là yếu tố quan trọng giúp bạn không chỉ biết đáp án mà còn hiểu phương pháp làm bài đúng đắn.

Từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề năng lượng tái tạo và giảm nghèo năng lượng được phân loại theo độ khó

Từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề năng lượng tái tạo và giảm nghèo năng lượng được phân loại theo độ khó

Phần từ vựng được tổng hợp từ cả 3 passages với hơn 40 từ và cụm từ quan trọng, kèm theo phiên âm, nghĩa tiếng Việt, ví dụ cụ thể và collocations sẽ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ vựng học thuật một cách có hệ thống. Những từ vựng này không chỉ hữu ích cho phần Reading mà còn có thể áp dụng vào Writing và Speaking.

Để đạt kết quả tốt nhất, hãy làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật với đúng thời gian quy định, sau đó đối chiếu đáp án và đọc kỹ phần giải thích để hiểu rõ lý do. Nếu bạn quan tâm đến các chủ đề liên quan, How clean energy is driving job creation cũng là một bài đọc bổ ích giúp mở rộng hiểu biết về năng lượng tái tạo trong bối cảnh phát triển kinh tế.

Chúc bạn ôn tập hiệu quả và đạt được band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!