Mở bài

Trong kỷ nguyên số hóa giáo dục, chủ đề về công nghệ và sự hợp tác trong môi trường học tập đang trở thành một trong những chủ đề phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading. Đặc biệt, “Virtual Art Studios For Student Collaboration” – các phòng tranh ảo dành cho sự hợp tác giữa sinh viên – là một chủ đề hiện đại, kết hợp giữa nghệ thuật, công nghệ và giáo dục, xuất hiện với tần suất ngày càng cao trong các đề thi IELTS gần đây.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một bộ đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages theo đúng chuẩn Cambridge, từ mức độ dễ đến khó. Bạn sẽ được thực hành với 40 câu hỏi đa dạng dạng, hoàn toàn giống như trong kỳ thi thật. Sau mỗi passage, bạn sẽ nhận được đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích rõ ràng, giúp bạn hiểu cách paraphrase và kỹ thuật làm bài hiệu quả. Đặc biệt, bài viết còn tổng hợp từ vựng quan trọng theo từng độ khó, giúp bạn nâng cao vốn từ vựng một cách có hệ thống.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên có trình độ từ band 5.0 trở lên, muốn rèn luyện kỹ năng đọc hiểu và làm quen với chủ đề công nghệ trong giáo dục nghệ thuật.

1. Hướng dẫn làm bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test là một phần quan trọng trong kỳ thi IELTS, đòi hỏi thí sinh hoàn thành 40 câu hỏi trong vòng 60 phút. Bài thi bao gồm 3 passages với độ dài và độ khó tăng dần, đánh giá khả năng đọc hiểu của bạn từ cơ bản đến nâng cao.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1 (Easy): 15-17 phút – Bài đọc ngắn nhất với từ vựng đơn giản

- Passage 2 (Medium): 18-20 phút – Bài đọc trung bình với độ phức tạp vừa phải

- Passage 3 (Hard): 23-25 phút – Bài đọc dài và phức tạp nhất, cần nhiều thời gian phân tích

Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được tính là 1 điểm, và tổng số điểm thô sẽ được quy đổi thành band score từ 1-9. Để đạt band 6.5, bạn cần trả lời đúng khoảng 27-29 câu; band 7.0 cần 30-32 câu đúng.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến nhất trong IELTS Reading:

- Multiple Choice – Câu hỏi trắc nghiệm với 3-4 lựa chọn

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng, sai hoặc không được đề cập

- Matching Information – Nối thông tin với đoạn văn tương ứng

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu với số từ giới hạn

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn phù hợp

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào đoạn tóm tắt

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn với số từ giới hạn

Mỗi dạng câu hỏi đòi hỏi kỹ năng đọc và chiến lược làm bài khác nhau. Hãy chú ý đến instructions để không mắc lỗi về format đáp án.

2. IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – The Rise of Digital Art Education

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

The transformation of art education through digital technology has been one of the most significant developments in modern pedagogy. Traditional art classrooms, with their physical canvases, brushes, and paints, are now being complemented and sometimes replaced by virtual art studios that allow students to create, share, and collaborate in entirely new ways. This shift has been particularly accelerated by the global pandemic, which forced educational institutions worldwide to seek alternative methods of instruction.

Virtual art studios are online platforms that provide students with digital tools to create artwork while enabling real-time collaboration with peers and instructors. Unlike conventional art classes where students work independently at their desks, these digital environments facilitate immediate feedback and collective creativity. Students can see each other’s work as it develops, offer suggestions, and even contribute directly to shared projects. This collaborative approach mirrors the way professional artists often work in the contemporary art world.

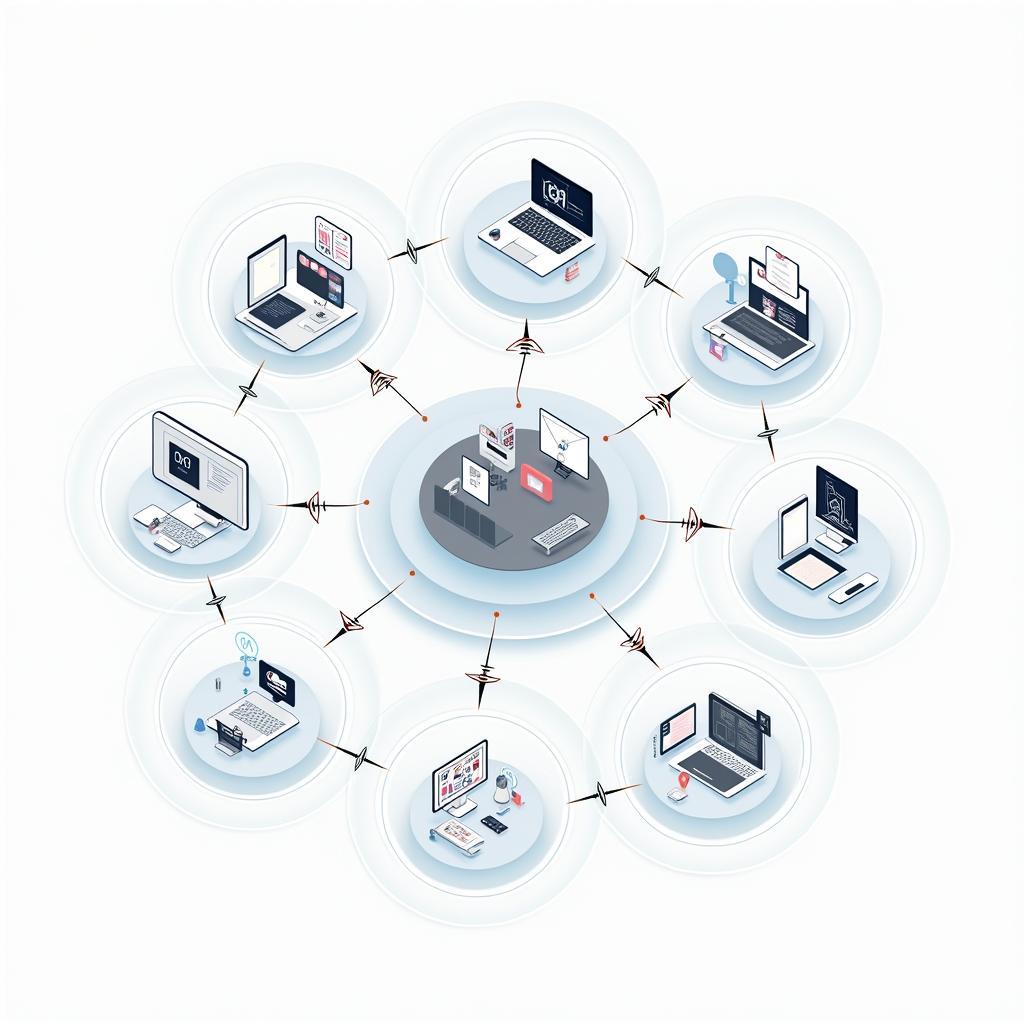

Phòng học nghệ thuật ảo với học sinh đang hợp tác sáng tạo trực tuyến trên màn hình máy tính

Phòng học nghệ thuật ảo với học sinh đang hợp tác sáng tạo trực tuyến trên màn hình máy tính

The accessibility of virtual art studios represents a major advantage over traditional settings. Students no longer need expensive art supplies or dedicated studio spaces. A basic computer or tablet with an internet connection provides access to professional-grade digital tools that would cost thousands of dollars in physical form. This democratization of art education has opened opportunities for students from various socioeconomic backgrounds who might otherwise be unable to pursue artistic interests.

Technical features of these platforms vary, but most include drawing and painting tools, layer management systems, and cloud storage for artwork. More advanced platforms integrate video conferencing, allowing students to discuss their work while creating it. Some systems employ artificial intelligence to provide automated suggestions for color combinations, composition improvements, or technique refinements. However, educators emphasize that these AI features should supplement rather than replace human instruction and creativity.

Teachers have observed several pedagogical benefits from using virtual art studios. First, the digital record of a student’s creative process – every brushstroke and revision – can be saved and reviewed, providing valuable insights into their artistic development. Second, the reduced fear of making mistakes in a digital environment encourages experimentation; students can easily undo actions without wasting materials. Third, the global connectivity allows classes to collaborate with students from different countries, exposing learners to diverse artistic traditions and perspectives.

However, challenges exist. Some educators worry that excessive reliance on digital tools might diminish students’ understanding of traditional art fundamentals such as color mixing with actual paints or the texture of different papers. There are also concerns about screen fatigue and the loss of tactile experience that comes from working with physical materials. Additionally, not all students have reliable internet access or suitable devices, creating a digital divide that can exclude some learners.

Despite these concerns, many art educators believe that virtual studios represent a complementary tool rather than a complete replacement for traditional methods. The most effective approaches integrate both digital and physical artmaking, allowing students to develop a comprehensive skill set. As one art teacher noted, “We’re not abandoning paintbrushes; we’re adding digital styluses to our toolkit.” This balanced perspective recognizes that future artists will likely need proficiency in both traditional and digital mediums.

The future of virtual art studios looks promising. Emerging technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are beginning to create even more immersive collaborative experiences. Students might soon be able to work together in three-dimensional virtual spaces, manipulating digital sculptures or installations as if they were physical objects. These developments could further blur the boundaries between traditional and digital art education, creating entirely new possibilities for creative collaboration among students worldwide.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

1. According to the passage, what has been the main driver of adopting virtual art studios?

A. The high cost of traditional art supplies

B. The global pandemic forcing remote learning

C. Student preference for digital tools

D. Professional artists using similar technology

2. What distinguishes virtual art studios from traditional art classrooms?

A. They are more expensive to set up

B. They require no teacher supervision

C. They enable immediate collaboration and feedback

D. They only work with advanced students

3. The passage suggests that AI features in virtual art platforms should:

A. Replace human teachers entirely

B. Be avoided in educational settings

C. Only be used by advanced students

D. Support but not substitute human instruction

4. What advantage do digital records of student work provide?

A. They take up less physical storage space

B. They show the complete creative process

C. They are easier to grade

D. They can be sold more easily

5. The author’s view on virtual art studios can best be described as:

A. Completely negative

B. Cautiously optimistic

C. Entirely enthusiastic

D. Fundamentally opposed

Questions 6-9: True/False/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the passage? Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

6. Virtual art studios require students to purchase expensive digital equipment.

7. All virtual art studio platforms include artificial intelligence features.

8. Some educators are concerned that digital tools might reduce understanding of traditional art techniques.

9. Virtual reality art education is currently available in most schools worldwide.

Questions 10-13: Sentence Completion

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

10. The __ of art education through technology has made artistic tools available to more students.

11. Students experience less __ when working digitally because they can easily correct errors.

12. Some students cannot participate due to a __ caused by lack of internet access.

13. Future developments may allow students to work in __ virtual spaces together.

PASSAGE 2 – Collaborative Creativity in Virtual Environments

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The pedagogical shift toward collaborative learning in art education represents a fundamental departure from the historically individualistic nature of artistic training. For centuries, the archetype of the solitary artist working in isolation has dominated both artistic practice and education. However, contemporary educational theory increasingly emphasizes social constructivism – the idea that knowledge and creativity develop through social interaction and shared experiences. Virtual art studios have emerged as powerful tools for implementing this philosophy, creating digital spaces where collective creativity can flourish in ways previously impossible.

Research into collaborative art-making reveals several cognitive benefits that extend beyond technical skill development. When students engage in joint creative projects, they must articulate their artistic vision, negotiate conflicting ideas, and integrate diverse perspectives into a coherent whole. These processes develop critical thinking skills, emotional intelligence, and the ability to give and receive constructive criticism – competencies increasingly valued in the 21st-century workplace. Dr. Sarah Martinez, an educational psychologist specializing in arts education, notes that “the metacognitive processes involved in collaborative art-making – planning, monitoring, and evaluating both individual and group work – are precisely the skills that transfer most effectively to other academic and professional domains.”

Virtual platforms facilitate collaboration through various mechanisms. Synchronous collaboration allows multiple students to work on the same digital canvas simultaneously, with each participant’s actions visible in real-time. This mode closely simulates the experience of artists working together on a large-scale mural or installation piece. Asynchronous collaboration, by contrast, enables students to contribute to shared projects at different times, with the platform maintaining a comprehensive revision history. This flexibility accommodates different schedules and learning rhythms while ensuring that all contributions are documented and attributable.

The design of virtual art studios reflects careful consideration of group dynamics and workflow optimization. Most platforms incorporate features such as layer-based editing, which allows individual students to work on separate elements of a composition without interfering with others’ contributions. Permission systems enable instructors to control access levels, determining who can view, comment on, or edit particular artworks. Integrated communication tools – including text chat, voice channels, and video conferencing – support the social dimension of collaboration, allowing students to discuss their work while creating it.

However, the transition to collaborative digital art-making presents significant challenges. Students accustomed to autonomous creative work may initially resist sharing control over artistic decisions. Research by Thompson and Liu (2019) found that approximately 40% of art students expressed anxiety about collaborative projects, fearing that group work would dilute their individual artistic voice or result in unequal contribution among team members. Addressing these concerns requires intentional pedagogical strategies, including clear role definitions, structured feedback protocols, and assessment methods that recognize both individual and collective contributions.

Cultural factors also influence how students engage with collaborative virtual environments. Studies indicate that students from collectivist cultural backgrounds often adapt more readily to collaborative art-making than those from individualist cultures, where personal achievement and distinctive style are more highly emphasized. Nevertheless, educators report that with appropriate scaffolding and team-building activities, students from all cultural backgrounds can develop effective collaborative practices. As one instructor observed, “The key is helping students understand that collaboration doesn’t erase individuality; it creates opportunities for individual strengths to complement each other.”

The assessment of collaborative artwork poses unique challenges for educators. Traditional art evaluation focuses on technical proficiency, originality, and aesthetic qualities – criteria that become complicated when multiple students contribute to a single piece. Some institutions have developed rubrics that separately evaluate individual contributions, collaborative processes, and final products. Others employ peer assessment mechanisms, asking students to reflect on their own and teammates’ contributions. These approaches recognize that the learning objectives for collaborative projects differ from those of individual assignments, with greater emphasis on interpersonal skills and creative problem-solving in group contexts.

Looking beyond immediate educational applications, collaborative virtual art studios are reshaping students’ preparation for professional creative careers. The contemporary art world increasingly values interdisciplinary collaboration, with artists frequently working alongside designers, programmers, scientists, and community members on large-scale projects. Similarly, creative industries – from animation and game design to advertising and user experience design – rely heavily on team-based production. By providing authentic collaborative experiences during their education, virtual art studios help students develop the interpersonal competencies and collaborative workflows they will need in their future careers. For educators looking to foster broader creative skills, understanding Arts fostering creativity and innovation provides valuable insights into how artistic practice develops innovative thinking across disciplines.

Emerging research explores how artificial intelligence and machine learning might enhance collaborative creativity in virtual studios. Some experimental platforms use AI algorithms to identify patterns in students’ collaborative behaviors, providing instructors with data about participation levels, creative contribution patterns, and potential conflicts. Other systems employ generative AI as a collaborative partner, suggesting ideas or creating variations on student work that teams can then refine. While these technologies remain controversial – with concerns about algorithmic bias and the authenticity of AI-assisted creativity – they represent a frontier in understanding how humans and machines might collaborate in creative endeavors.

Học sinh từ nhiều quốc gia đang cùng làm việc trên dự án nghệ thuật số qua nền tảng ảo

Học sinh từ nhiều quốc gia đang cùng làm việc trên dự án nghệ thuật số qua nền tảng ảo

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18: Yes/No/Not Given

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in the passage? Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

14. Traditional art education has always emphasized collaborative learning approaches.

15. Collaborative art-making helps develop skills that are useful beyond artistic contexts.

16. Synchronous collaboration is more effective than asynchronous collaboration for learning.

17. Most art students initially feel comfortable with collaborative digital projects.

18. Students from collectivist cultures always perform better in collaborative environments.

Questions 19-22: Matching Headings

The passage has nine paragraphs. Choose the correct heading for paragraphs C, E, G, and I from the list of headings below.

List of Headings:

i. The role of AI in future collaborative art

ii. Technical features supporting group work

iii. Financial barriers to implementing virtual studios

iv. Cultural influences on collaborative behavior

v. Benefits beyond artistic skill development

vi. Methods for evaluating group artwork

vii. The history of art education

viii. Professional preparation through collaboration

19. Paragraph C __

20. Paragraph E __

21. Paragraph G __

22. Paragraph I __

Questions 23-26: Summary Completion

Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Virtual art studios support collaboration through different approaches. In (23) __, multiple students work on the same project at the same time, similar to creating a mural together. The platforms include useful features like (24) __, which let students work on different parts without affecting others’ work. However, some students feel (25) __ about collaborative projects, worrying that their personal artistic style might be lost. To address this, teachers need to use specific **(26) __ that help students work together effectively.

PASSAGE 3 – The Socio-Technical Architecture of Virtual Collaborative Art Spaces

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The proliferation of virtual art studios designed for student collaboration represents more than a simple technological substitution for physical classrooms; it embodies a complex socio-technical system wherein pedagogical objectives, technological affordances, and social dynamics intersect to create entirely new epistemological frameworks for understanding artistic learning. Contemporary educational technology research increasingly recognizes that the efficacy of digital learning environments depends not merely on their technical capabilities but on how these technologies are appropriated, adapted, and sometimes subverted by users within specific educational contexts. This perspective, drawing on Actor-Network Theory and socio-cultural learning theories, positions virtual art studios as mediating artifacts that both enable and constrain particular forms of collaborative creative practice.

The architectural design of virtual collaborative platforms reflects underlying assumptions about the nature of creativity, collaboration, and learning. Interface design decisions – such as whether students see each other’s work processes in real-time or only view finished contributions – fundamentally shape the phenomenology of collaborative experience. Platforms emphasizing synchronous, transparent workflows tend to foster emergent creativity, where ideas develop through dynamic interaction and spontaneous modification of each other’s work. Conversely, systems structured around sequential contribution with clear delineation of individual inputs may better support students who require psychological safety and defined boundaries around their creative contributions. Research by Nakamura et al. (2021) demonstrates that these design affordances disproportionately affect students with different cognitive styles and anxiety profiles, suggesting that no single platform architecture optimally serves all learners.

The concept of distributed cognition provides a useful theoretical lens for understanding collaborative art-making in virtual environments. This framework posits that cognitive processes extend beyond individual minds to encompass external representations, artifacts, and social interactions. In virtual art studios, cognition is distributed across human participants, digital tools, and the collaborative artifacts they jointly create. The version control systems that track every modification to a shared artwork function as externalized memory, allowing the group to maintain awareness of the project’s evolution. Algorithmic recommendation systems that suggest color palettes or compositional arrangements act as cognitive prosthetics, extending students’ creative problem-solving capabilities. The communicative infrastructure – text chat, voice channels, annotation tools – serves as the medium through which collective intentionality is negotiated and coordinated.

However, this distribution of agency across human and non-human actors raises profound questions about authorship and creative ownership in collaborative contexts. When multiple students contribute to a digital artwork alongside AI-generated suggestions and algorithmically optimized elements, traditional notions of the autonomous creative subject become increasingly untenable. This decentering of authorship aligns with postmodern artistic theory but conflicts with institutional structures – including assessment systems, intellectual property frameworks, and cultural narratives – that presume individual creative genius. Educational institutions grappling with these tensions have developed varied responses, from collective authorship models that credit all contributors equally to granular attribution systems that attempt to trace each element to its originator, though the latter approach may undermine the integrative nature of truly collaborative work.

The sociological dimensions of virtual collaborative art spaces merit particular attention, as these environments both reflect and potentially transform status hierarchies and power relations within educational settings. Research on computer-mediated communication suggests that digital environments can sometimes attenuate status characteristics such as race, gender, or physical appearance that might influence face-to-face interactions, potentially creating more egalitarian collaborative dynamics. However, other studies indicate that digital divides – differential access to technology and digital literacy – can reproduce or even amplify existing inequalities. Furthermore, the persistence and traceability of all actions in digital environments creates new forms of surveillance that may inhibit risk-taking and experimentation, particularly for students already experiencing evaluative anxiety.

The cultural epistemologies embedded in virtual art platforms warrant critical examination. Most widely-used platforms originate in Western contexts and reflect Euro-American artistic traditions, individualist cultural values, and assumptions about creative pedagogy that may not align with diverse cultural practices. The emphasis on explicit verbal communication about creative decisions may disadvantage students from cultures where artistic knowledge is transmitted through demonstration, observation, and tacit learning. The privileging of visual art forms that translate readily to digital formats may marginalize artistic traditions centered on materiality, site-specificity, or performative embodiment. Educators working with culturally diverse student populations must therefore critically assess how platform designs might inadvertently impose cultural hegemony and consider culturally responsive adaptations that honor diverse ways of knowing and creating. In this context, exploring the use of animation in teaching cultural diversity demonstrates how digital tools can be adapted to represent and celebrate multiple cultural perspectives in educational settings.

Longitudinal studies examining the developmental trajectories of students engaged in sustained virtual collaboration reveal both encouraging findings and areas requiring further investigation. On positive dimensions, students who participate regularly in collaborative virtual projects demonstrate enhanced metacognitive awareness about their creative processes, improved capacity for constructive peer critique, and greater cognitive flexibility in adapting their artistic approaches. However, some research suggests potential trade-offs: students primarily trained in virtual environments sometimes exhibit decreased material literacy – diminished understanding of how physical art materials behave – and may develop over-reliance on digital correction tools that inhibits the productive struggle essential to deep learning.

The ecological validity of research on virtual art studios presents methodological challenges. Most studies occur in controlled or semi-controlled settings with motivated volunteer participants, potentially limiting generalizability to authentic educational contexts where participation may be mandatory and technological proficiency varies widely. Additionally, the rapid evolution of platform capabilities means that findings from studies conducted even two to three years ago may have limited applicability to current systems. This temporal instability complicates efforts to develop evidence-based pedagogical recommendations, suggesting the need for agile research methodologies that can keep pace with technological change.

Looking toward future developments, several emergent technologies promise to further transform collaborative virtual art education. Haptic feedback systems that simulate the tactile experience of working with physical materials could address concerns about the loss of embodied learning in digital environments. Immersive virtual reality platforms capable of supporting multi-user environments might enable three-dimensional collaborative sculpture and installation art that transcends the limitations of two-dimensional screens. Blockchain-based attribution systems could provide transparent, immutable records of individual contributions to collaborative works, potentially resolving questions of authorship while maintaining the integrity of collective creation. However, each technological advancement introduces new equity concerns, as high-end equipment requirements may exacerbate access disparities.

Ultimately, the integration of virtual art studios into educational practice requires continuous reflexive evaluation that attends to both opportunities and constraints these technologies introduce. Rather than viewing digital platforms as neutral tools that simply facilitate pre-existing pedagogical goals, educators must recognize them as active agents that shape what forms of learning become possible, valued, and assessed. This critical techno-pedagogical literacy – the capacity to analyze how technologies embody particular assumptions and affect learning processes – represents an essential professional competency for contemporary art educators navigating increasingly technology-mediated educational landscapes.

Kiến trúc kỹ thuật phức tạp của nền tảng nghệ thuật ảo với các tính năng hợp tác nâng cao

Kiến trúc kỹ thuật phức tạp của nền tảng nghệ thuật ảo với các tính năng hợp tác nâng cao

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31: Multiple Choice

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

27. According to the passage, virtual art studios are best understood as:

A. Simple technological replacements for physical classrooms

B. Complex systems where technology and social factors interact

C. Tools that function the same way in all educational contexts

D. Technologies that work independently of how users employ them

28. The concept of distributed cognition suggests that:

A. Students should work individually rather than collaboratively

B. Cognitive processes only occur within individual minds

C. Thinking extends beyond individuals to include tools and interactions

D. Artificial intelligence can fully replace human creativity

29. The passage indicates that traditional notions of authorship are challenged by:

A. Students refusing to share credit for their work

B. Multiple contributors including humans and AI creating work together

C. Teachers taking credit for student artwork

D. The high cost of digital art platforms

30. Research on computer-mediated communication suggests that digital environments:

A. Always create more equal collaborative dynamics

B. Consistently reproduce existing social inequalities

C. May reduce some status differences but introduce other concerns

D. Have no effect on power relations among students

31. The author’s attitude toward haptic feedback systems can best be described as:

A. Entirely enthusiastic without reservations

B. Completely dismissive of their potential value

C. Cautiously optimistic but concerned about equity

D. Neutral and uninterested in future developments

Questions 32-36: Matching Features

Match each statement (32-36) with the correct researcher or research finding (A-H) from the passage.

A. Nakamura et al. (2021)

B. Research on computer-mediated communication

C. Longitudinal studies

D. Actor-Network Theory

E. Postmodern artistic theory

F. Research by Thompson and Liu (2019)

G. Studies on digital divides

H. Ecological validity research

32. Found that approximately 40% of art students felt anxious about group projects __

33. Showed that platform design affects students differently based on their cognitive styles __

34. Revealed that students develop better metacognitive awareness through sustained collaboration __

35. Positions technologies as mediating artifacts in educational contexts __

36. Indicates that most research may not reflect real classroom conditions __

Questions 37-40: Short-answer Questions

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

37. What kind of systems track every change made to a shared artwork and function as externalized memory?

38. What type of literacy do students sometimes lose when primarily trained in virtual environments?

39. What kind of evaluation does the author say is necessary when integrating virtual art studios into education?

40. What professional competency must contemporary art educators develop to understand how technologies affect learning?

3. Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- B

- C

- D

- B

- B

- FALSE

- NOT GIVEN

- TRUE

- NOT GIVEN

- democratization

- fear of mistakes

- digital divide

- three-dimensional

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- NO

- YES

- NOT GIVEN

- NO

- NOT GIVEN

- ii

- iv

- vi

- i

- synchronous collaboration

- layer-based editing

- anxiety

- pedagogical strategies

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- C

- B

- C

- C

- F

- A

- C

- D

- H

- version control systems

- material literacy

- reflexive evaluation

- critical techno-pedagogical literacy

4. Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: main driver, adopting virtual art studios

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn A, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “This shift has been particularly accelerated by the global pandemic, which forced educational institutions worldwide to seek alternative methods of instruction.” Đáp án A và D có được đề cập nhưng không phải là main driver. Đáp án C không được đề cập trong bài.

Câu 2: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: distinguishes, virtual art studios, traditional classrooms

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn B, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “Unlike conventional art classes where students work independently at their desks, these digital environments facilitate immediate feedback and collective creativity” – câu này paraphrase thành “enable immediate collaboration and feedback” ở đáp án C.

Câu 6: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: require, purchase expensive digital equipment

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói “Students no longer need expensive art supplies” và “A basic computer or tablet with an internet connection provides access”, mâu thuẫn trực tiếp với câu hỏi nên đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 8: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: educators concerned, digital tools, reduce understanding, traditional techniques

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn F, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Some educators worry that excessive reliance on digital tools might diminish students’ understanding of traditional art fundamentals” – khớp hoàn toàn với ý của câu hỏi.

Câu 10: democratization

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: art education through technology, available to more students

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “This democratization of art education has opened opportunities for students from various socioeconomic backgrounds” – từ “democratization” chính xác mô tả việc làm cho giáo dục nghệ thuật trở nên dễ tiếp cận hơn.

Câu 12: digital divide

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: cannot participate, lack of internet access

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn F, dòng cuối

- Giải thích: “Additionally, not all students have reliable internet access or suitable devices, creating a digital divide that can exclude some learners” – cụm “digital divide” giải thích chính xác rào cản do thiếu truy cập internet.

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Traditional art education, always emphasized collaborative learning

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn A, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “For centuries, the archetype of the solitary artist working in isolation has dominated both artistic practice and education” – điều này trực tiếp mâu thuẫn với câu hỏi, cho thấy giáo dục nghệ thuật truyền thống KHÔNG nhấn mạnh collaborative learning.

Câu 15: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Collaborative art-making, develop skills, useful beyond artistic contexts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn B, dòng 1-7

- Giải thích: “Research into collaborative art-making reveals several cognitive benefits that extend beyond technical skill development” và đoạn văn liệt kê các kỹ năng như critical thinking, emotional intelligence được đánh giá cao trong “21st-century workplace”.

Câu 17: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Most art students, initially feel comfortable, collaborative digital projects

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn E, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Research by Thompson and Liu (2019) found that approximately 40% of art students expressed anxiety about collaborative projects” – 40% cảm thấy lo lắng cho thấy nhiều học sinh KHÔNG cảm thấy thoải mái ban đầu.

Câu 19: ii (Technical features supporting group work)

- Vị trí: Đoạn C (Paragraph C)

- Giải thích: Đoạn này tập trung mô tả các tính năng kỹ thuật của nền tảng như layer-based editing, permission systems, integrated communication tools – tất cả hỗ trợ làm việc nhóm.

Câu 23: synchronous collaboration

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: multiple students work on same project at same time

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Synchronous collaboration allows multiple students to work on the same digital canvas simultaneously” – khớp chính xác với mô tả trong summary.

Câu 25: anxiety

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: students feel, about collaborative projects

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn E, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “approximately 40% of art students expressed anxiety about collaborative projects” – từ “anxiety” là từ chính xác được sử dụng trong bài.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: virtual art studios, best understood as

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn A, dòng 1-5

- Giải thích: Câu mở đầu nói rõ “represents more than a simple technological substitution” và “embodies a complex socio-technical system wherein pedagogical objectives, technological affordances, and social dynamics intersect” – chính xác là đáp án B.

Câu 28: C

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: distributed cognition suggests

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “This framework posits that cognitive processes extend beyond individual minds to encompass external representations, artifacts, and social interactions” – paraphrase chính xác thành đáp án C.

Câu 29: B

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: traditional notions of authorship, challenged by

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn D, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “When multiple students contribute to a digital artwork alongside AI-generated suggestions and algorithmically optimized elements, traditional notions of the autonomous creative subject become increasingly untenable” – mô tả việc nhiều người và AI cùng tạo tác phẩm.

Câu 32: F (Thompson and Liu, 2019)

- Từ khóa: 40% of art students felt anxious

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn E (Passage 2), dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Research by Thompson and Liu (2019) found that approximately 40% of art students expressed anxiety about collaborative projects”

Câu 37: version control systems

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions

- Từ khóa: track every change, shared artwork, externalized memory

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn C, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: “The version control systems that track every modification to a shared artwork function as externalized memory” – chính xác là 3 từ cần tìm.

Câu 40: critical techno-pedagogical literacy

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Questions (không quá 3 từ, nhưng đây là cụm thuật ngữ cố định)

- Từ khóa: professional competency, contemporary art educators, understand how technologies affect learning

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn J, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “This critical techno-pedagogical literacy – the capacity to analyze how technologies embody particular assumptions and affect learning processes – represents an essential professional competency”

5. Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| complement | v | /ˈkɒmplɪment/ | bổ sung, hoàn thiện | Traditional classrooms are now being complemented by virtual studios | complement each other, perfectly complement |

| facilitate | v | /fəˈsɪlɪteɪt/ | tạo điều kiện, hỗ trợ | These environments facilitate immediate feedback | facilitate learning, facilitate communication |

| real-time | adj | /ˌriːəl ˈtaɪm/ | thời gian thực | Enable real-time collaboration with peers | real-time feedback, real-time monitoring |

| democratization | n | /dɪˌmɒkrətaɪˈzeɪʃən/ | dân chủ hóa, phổ cập | This democratization of art education | democratization of access, democratization of knowledge |

| accessibility | n | /əkˌsesəˈbɪləti/ | khả năng tiếp cận | The accessibility of virtual art studios | improve accessibility, ensure accessibility |

| socioeconomic | adj | /ˌsəʊsiəʊˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk/ | thuộc về kinh tế xã hội | Students from various socioeconomic backgrounds | socioeconomic status, socioeconomic factors |

| layer management | n phrase | /ˈleɪə ˈmænɪdʒmənt/ | quản lý lớp (trong đồ họa) | Most include layer management systems | layer management tools, efficient layer management |

| pedagogical | adj | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkəl/ | thuộc về sư phạm | Teachers observed several pedagogical benefits | pedagogical approach, pedagogical strategy |

| tactile | adj | /ˈtæktaɪl/ | thuộc về xúc giác | Loss of tactile experience | tactile feedback, tactile sensation |

| digital divide | n phrase | /ˈdɪdʒɪtəl dɪˈvaɪd/ | khoảng cách kỹ thuật số | Creating a digital divide | bridge the digital divide, widen the digital divide |

| immersive | adj | /ɪˈmɜːsɪv/ | đắm chìm, nhập vai | More immersive collaborative experiences | immersive experience, immersive environment |

| augmented reality | n phrase | /ɔːɡˌmentɪd riˈæləti/ | thực tế tăng cường | Technologies such as augmented reality | augmented reality applications, augmented reality devices |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pedagogical shift | n phrase | /ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkəl ʃɪft/ | sự chuyển đổi sư phạm | The pedagogical shift toward collaborative learning | significant pedagogical shift, major pedagogical shift |

| individualistic | adj | /ˌɪndɪˌvɪdʒuəˈlɪstɪk/ | theo chủ nghĩa cá nhân | The individualistic nature of artistic training | individualistic approach, individualistic culture |

| social constructivism | n phrase | /ˈsəʊʃəl kənˈstrʌktɪvɪzəm/ | chủ nghĩa kiến tạo xã hội | Educational theory emphasizes social constructivism | principles of social constructivism, social constructivism theory |

| metacognitive | adj | /ˌmetəˈkɒɡnətɪv/ | thuộc về siêu nhận thức | The metacognitive processes involved | metacognitive skills, metacognitive awareness |

| synchronous | adj | /ˈsɪŋkrənəs/ | đồng bộ | Synchronous collaboration allows real-time work | synchronous learning, synchronous communication |

| asynchronous | adj | /eɪˈsɪŋkrənəs/ | không đồng bộ | Asynchronous collaboration enables flexible timing | asynchronous learning, asynchronous discussion |

| workflow optimization | n phrase | /ˈwɜːkfləʊ ˌɒptɪmaɪˈzeɪʃən/ | tối ưu hóa quy trình | Design reflects workflow optimization | workflow optimization strategies, improve workflow optimization |

| scaffolding | n | /ˈskæfəldɪŋ/ | giàn giáo, hỗ trợ học tập | With appropriate scaffolding | instructional scaffolding, provide scaffolding |

| rubric | n | /ˈruːbrɪk/ | tiêu chí đánh giá | Institutions have developed rubrics | assessment rubric, grading rubric |

| interdisciplinary | adj | /ˌɪntəˈdɪsəplɪnəri/ | liên ngành | The art world values interdisciplinary collaboration | interdisciplinary approach, interdisciplinary research |

| generative AI | n phrase | /ˈdʒenərətɪv eɪ aɪ/ | AI sinh tạo | Systems employ generative AI | generative AI tools, generative AI models |

| algorithmic bias | n phrase | /ˌælɡəˈrɪðmɪk ˈbaɪəs/ | thiên kiến thuật toán | Concerns about algorithmic bias | address algorithmic bias, reduce algorithmic bias |

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ tiếng Anh | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| socio-technical system | n phrase | /ˌsəʊsiəʊ ˈteknɪkəl ˈsɪstəm/ | hệ thống kỹ thuật xã hội | Embodies a complex socio-technical system | analyze socio-technical systems, design socio-technical systems |

| epistemological | adj | /ɪˌpɪstəməˈlɒdʒɪkəl/ | thuộc về nhận thức luận | New epistemological frameworks | epistemological assumptions, epistemological perspective |

| technological affordances | n phrase | /ˌteknəˈlɒdʒɪkəl əˈfɔːdənsɪz/ | khả năng công nghệ | Technical capabilities and affordances | design affordances, explore affordances |

| Actor-Network Theory | n phrase | /ˈæktə ˈnetwɜːk ˈθɪəri/ | lý thuyết mạng lưới tác nhân | Drawing on Actor-Network Theory | apply Actor-Network Theory, Actor-Network Theory perspective |

| phenomenology | n | /fɪˌnɒməˈnɒlədʒi/ | hiện tượng học | The phenomenology of collaborative experience | phenomenology of perception, phenomenological approach |

| emergent creativity | n phrase | /ɪˈmɜːdʒənt ˌkriːeɪˈtɪvəti/ | sáng tạo mới nổi | Tend to foster emergent creativity | support emergent creativity, cultivate emergent creativity |

| distributed cognition | n phrase | /dɪˈstrɪbjuːtɪd kɒɡˈnɪʃən/ | nhận thức phân tán | The concept of distributed cognition | theory of distributed cognition, distributed cognition framework |

| cognitive prosthetics | n phrase | /ˈkɒɡnətɪv prɒsˈθetɪks/ | bộ phận nhận thức nhân tạo | Act as cognitive prosthetics | use cognitive prosthetics, develop cognitive prosthetics |

| decentering of authorship | n phrase | /diːˈsentərɪŋ ɒv ˈɔːθəʃɪp/ | phi trung tâm hóa quyền tác giả | This decentering of authorship | explore decentering of authorship, challenge traditional authorship |

| status hierarchies | n phrase | /ˈsteɪtəs ˈhaɪərɑːkiz/ | thứ bậc địa vị | Transform status hierarchies | maintain status hierarchies, challenge status hierarchies |

| egalitarian | adj | /ɪˌɡælɪˈteəriən/ | bình đẳng | More egalitarian collaborative dynamics | egalitarian approach, egalitarian society |

| cultural hegemony | n phrase | /ˈkʌltʃərəl hɪˈɡeməni/ | bá quyền văn hóa | May inadvertently impose cultural hegemony | challenge cultural hegemony, cultural hegemony theory |

| tacit learning | n phrase | /ˈtæsɪt ˈlɜːnɪŋ/ | học ngầm | Transmitted through tacit learning | tacit learning process, support tacit learning |

| longitudinal studies | n phrase | /ˌlɒndʒɪˈtjuːdɪnəl ˈstʌdiz/ | nghiên cứu dọc | Longitudinal studies examining trajectories | conduct longitudinal studies, longitudinal studies show |

| ecological validity | n phrase | /ˌiːkəˈlɒdʒɪkəl vəˈlɪdəti/ | tính hợp lệ sinh thái | The ecological validity of research | ensure ecological validity, improve ecological validity |

| haptic feedback | n phrase | /ˈhæptɪk ˈfiːdbæk/ | phản hồi xúc giác | Haptic feedback systems | provide haptic feedback, haptic feedback technology |

| reflexive evaluation | n phrase | /rɪˈfleksɪv ɪˌvæljuˈeɪʃən/ | đánh giá phản tư | Requires continuous reflexive evaluation | engage in reflexive evaluation, reflexive evaluation process |

| techno-pedagogical literacy | n phrase | /ˌteknəʊ ˌpedəˈɡɒdʒɪkəl ˈlɪtərəsi/ | hiểu biết kỹ thuật sư phạm | Critical techno-pedagogical literacy | develop techno-pedagogical literacy, techno-pedagogical literacy skills |

Kết bài

Chủ đề “Virtual art studios for student collaboration” không chỉ phản ánh xu hướng số hóa giáo dục hiện đại mà còn thể hiện sự giao thoa giữa nghệ thuật, công nghệ và các phương pháp học tập hợp tác. Qua bộ đề thi mẫu này, bạn đã được trải nghiệm đầy đủ ba mức độ khó từ Easy đến Hard, với tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi đa dạng dạng, hoàn toàn giống với cấu trúc thi IELTS Reading thật.

Ba passages trong đề thi đã cung cấp góc nhìn toàn diện về phòng tranh ảo: từ những lợi ích cơ bản và cách thức hoạt động (Passage 1), đến các khía cạnh sư phạm và tâm lý học của học tập hợp tác (Passage 2), cho đến những phân tích học thuật sâu sắc về kiến trúc kỹ thuật xã hội và các vấn đề về quyền tác giả, văn hóa (Passage 3). Phần đáp án chi tiết đã giúp bạn hiểu rõ cách xác định thông tin trong bài, kỹ thuật paraphrase, và cách tiếp cận từng dạng câu hỏi một cách hiệu quả.

Đặc biệt, phần từ vựng được phân loại theo từng passage giúp bạn xây dựng vốn từ vựng học thuật cần thiết không chỉ cho IELTS Reading mà còn cho Writing và Speaking. Những từ như “pedagogical shift”, “distributed cognition”, “epistemological frameworks” hay “techno-pedagogical literacy” là những thuật ngữ quan trọng trong các bài đọc học thuật hiện đại.

Hãy sử dụng đề thi này như một công cụ luyện tập thực chiến. Đặt thời gian 60 phút, làm bài trong điều kiện thi thật, sau đó đối chiếu đáp án và đọc kỹ phần giải thích để hiểu sâu hơn về cách làm bài. Chúc bạn đạt được band điểm mong muốn trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!