Mở bài

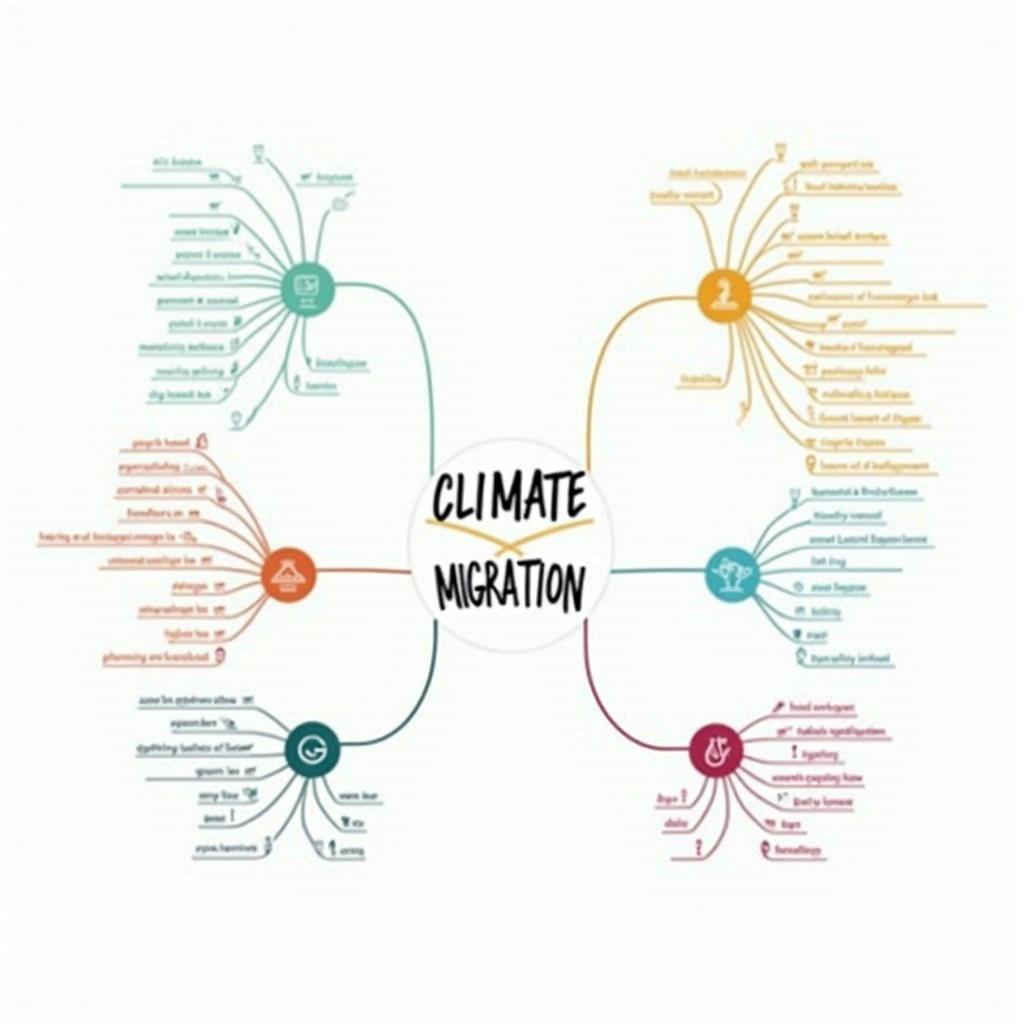

Biến đổi khí hậu đang tạo ra một trong những thách thức di cư lớn nhất thế kỷ 21. Hàng triệu người trên toàn cầu phải rời bỏ quê hương do hạn hán, lũ lụt, mực nước biển dâng và các thảm họa tự nhiên ngày càng gia tăng. Chủ đề “What Are The Challenges Of Managing Global Migration Due To Climate Change?” thường xuyên xuất hiện trong IELTS Reading với tần suất cao, đặc biệt trong các bài thi gần đây từ 2020 đến nay.

Bài viết này cung cấp cho bạn một đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh với 3 passages được thiết kế theo đúng chuẩn Cambridge IELTS, bao gồm 40 câu hỏi đa dạng từ dễ đến khó. Bạn sẽ được luyện tập với các dạng câu hỏi phổ biến như True/False/Not Given, Multiple Choice, Matching Headings và nhiều dạng khác. Mỗi câu hỏi đều có đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích cụ thể về vị trí thông tin và kỹ thuật paraphrase. Bên cạnh đó, bài viết còn tổng hợp từ vựng quan trọng được phân loại theo độ khó, giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ học thuật về môi trường và di cư.

Đề thi này phù hợp cho học viên từ band 5.0 trở lên, giúp bạn làm quen với áp lực thời gian và độ khó thực tế của kỳ thi IELTS Reading.

Hướng Dẫn Làm Bài IELTS Reading

Tổng Quan Về IELTS Reading Test

IELTS Reading Test kéo dài 60 phút với 3 passages và tổng cộng 40 câu hỏi. Không có thời gian phụ để chuyển đáp án sang phiếu trả lời, vì vậy bạn cần quản lý thời gian cẩn thận.

Phân bổ thời gian khuyến nghị:

- Passage 1: 15-17 phút (độ khó dễ, 13 câu)

- Passage 2: 18-20 phút (độ khó trung bình, 13 câu)

- Passage 3: 23-25 phút (độ khó cao, 14 câu)

Mỗi câu trả lời đúng được 1 điểm, sau đó quy đổi thành band score từ 0-9.

Các Dạng Câu Hỏi Trong Đề Này

Đề thi mẫu này bao gồm 7 dạng câu hỏi phổ biến:

- True/False/Not Given – Xác định thông tin đúng/sai/không đề cập

- Multiple Choice – Chọn đáp án đúng từ các phương án cho sẵn

- Matching Headings – Nối tiêu đề với đoạn văn phù hợp

- Sentence Completion – Hoàn thành câu với từ trong bài

- Summary Completion – Điền từ vào tóm tắt đoạn văn

- Matching Features – Nối thông tin với nhân vật/tổ chức

- Short-answer Questions – Trả lời câu hỏi ngắn

IELTS Reading Practice Test

PASSAGE 1 – Climate Refugees: A Growing Global Challenge

Độ khó: Easy (Band 5.0-6.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 15-17 phút

Climate change is fundamentally transforming the way people live across the globe, forcing millions to leave their homes in search of safer environments. Climate refugees, also known as environmental migrants, are individuals who must relocate due to sudden or progressive changes in their local environment caused by climate-related factors. Unlike traditional refugees fleeing war or persecution, climate refugees face a unique set of challenges that are not yet fully recognized under international law.

The phenomenon of climate-induced migration is not entirely new, but its scale is unprecedented. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, weather-related disasters displaced approximately 23.9 million people in 2019 alone. This figure represents nearly three times the number of people displaced by conflict and violence during the same period. Extreme weather events such as hurricanes, floods, and droughts are becoming more frequent and severe, directly impacting communities in vulnerable regions. Small island nations like Tuvalu and the Maldives face the threat of complete submersion due to rising sea levels, while countries in sub-Saharan Africa experience prolonged droughts that devastate agriculture and livelihoods.

The drivers of climate migration are complex and multifaceted. Slow-onset events such as desertification, sea-level rise, and glacial retreat gradually erode people’s ability to sustain themselves in their traditional homelands. For example, in Bangladesh, coastal erosion destroys approximately 20 hectares of land daily, pushing thousands of families inland each year. Conversely, sudden-onset disasters like cyclones or flash floods can displace entire communities overnight. In 2020, Cyclone Amphan forced over 2.4 million people to evacuate in India and Bangladesh, demonstrating how rapidly climate events can trigger mass movement.

Rural-to-urban migration represents the most common pattern of climate-related movement. Farmers whose crops fail due to irregular rainfall patterns often move to cities seeking employment opportunities. This internal migration places enormous pressure on urban infrastructure, leading to the expansion of informal settlements with inadequate access to clean water, sanitation, and healthcare. Cities like Dhaka in Bangladesh have seen their populations swell dramatically, with climate migrants comprising a significant proportion of new arrivals. These urban centers struggle to absorb the influx while maintaining quality of life for existing residents.

International migration driven by climate factors presents even greater challenges. When environmental conditions deteriorate beyond a certain threshold, people may cross national borders in search of refuge. However, current international frameworks do not adequately address their needs. The 1951 Refugee Convention, which forms the basis of refugee protection, does not recognize environmental factors as grounds for refugee status. This legal gap leaves climate refugees in a precarious position, often unable to access the protections and assistance available to conventional refugees. Some experts argue for expanding the definition of refugees, while others propose creating entirely new legal categories specifically for climate migrants.

The socioeconomic impacts of climate migration extend far beyond the migrants themselves. Sending regions experience brain drain as younger, more educated individuals are typically the first to leave, depleting communities of vital human capital. Agricultural productivity may decline further as the workforce diminishes, creating a vicious cycle of environmental degradation and outmigration. Meanwhile, receiving areas face challenges in providing services, employment, and social integration for newcomers. Tensions between host communities and migrants can arise, particularly when resources are scarce or when cultural differences are pronounced.

Women and children constitute the most vulnerable groups among climate migrants. Traditional gender roles often mean that men migrate first for work, leaving women to manage households in increasingly difficult conditions. When entire families do relocate, women may face exploitation and gender-based violence during transit or in destination areas. Children’s education is frequently disrupted, sometimes permanently, affecting their long-term prospects. Health risks also escalate during migration, with limited access to medical care and exposure to new diseases in unfamiliar environments.

Despite these challenges, climate migration is not solely a story of victimhood. Many migrants demonstrate remarkable resilience and adaptability, establishing new livelihoods and contributing to their destination communities. Remittances sent by migrants back to their home regions provide crucial financial support, helping families left behind to cope with environmental stresses. Some communities have developed innovative adaptation strategies, combining migration with other responses such as improved agricultural techniques or diversification of income sources. Understanding migration as one element of a broader adaptation toolkit, rather than a failure to adapt, offers a more nuanced perspective on this complex phenomenon.

Questions 1-13

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

Write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

-

Climate refugees are officially recognized under the same international laws as refugees fleeing war.

-

In 2019, more people were displaced by weather-related disasters than by armed conflicts.

-

The Maldives has already been completely submerged due to rising sea levels.

-

Bangladesh loses approximately 20 hectares of coastal land every day.

-

All climate migrants who cross international borders can access the same protections as conventional refugees.

Questions 6-9

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

Events such as desertification and glacial retreat are examples of __ that gradually force people to leave their homes.

-

The most typical movement pattern for climate migrants is __ migration.

-

When productive younger people leave rural areas, their home regions suffer from __.

-

Money sent back home by migrants, known as __, helps families cope with environmental difficulties.

Questions 10-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- According to the passage, what was the approximate number of people displaced by climate-related disasters in 2019?

- A. 2.4 million

- B. 20 million

- C. 23.9 million

- D. 30 million

- Which of the following is mentioned as a consequence of rural-to-urban climate migration?

- A. Decreased food prices in cities

- B. Growth of informal settlements

- C. Improved healthcare access

- D. Reduced urban employment

- What does the passage say about the 1951 Refugee Convention?

- A. It specifically addresses climate refugees

- B. It was updated to include environmental migrants

- C. It does not recognize environmental factors for refugee status

- D. It applies only to African nations

- According to the passage, which group is identified as most vulnerable among climate migrants?

- A. Elderly people

- B. Government officials

- C. Young men

- D. Women and children

PASSAGE 2 – Policy Responses to Climate Migration: Challenges and Opportunities

Độ khó: Medium (Band 6.0-7.5)

Thời gian đề xuất: 18-20 phút

The governance of climate-induced migration represents one of the most formidable challenges facing the international community in the twenty-first century. As environmental degradation accelerates and climate patterns become increasingly unpredictable, the number of people compelled to relocate is projected to rise dramatically. Estimates suggest that by 2050, anywhere between 150 million and 1 billion people could be displaced by climate change, though the methodological uncertainties inherent in such projections are considerable. This anticipated surge in climate migration necessitates comprehensive policy frameworks that balance humanitarian concerns with practical considerations of state sovereignty, resource allocation, and social cohesion.

Current international legal and institutional architectures are ill-equipped to address the multidimensional nature of climate migration. The dichotomy between voluntary migration and forced displacement becomes blurred when environmental degradation gradually erodes livelihoods over extended periods. A farmer facing declining crop yields due to changing rainfall patterns may technically have the option to remain, but deteriorating conditions effectively eliminate meaningful choice. This conceptual ambiguity complicates efforts to establish clear legal definitions and protection mechanisms. Furthermore, the distinction between internal and cross-border movement carries significant implications for governance, as states possess sovereign rights to control international migration but have obligations regarding the welfare of their own displaced citizens.

Several multilateral initiatives have emerged to address gaps in climate migration governance. The 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration acknowledges climate change as a driver of migration and commits signatory states to develop adaptation and resilience strategies. The Nansen Initiative, launched in 2012, seeks to build consensus on how to address the protection needs of people displaced across borders by natural disasters, including those linked to climate change. These frameworks, however, remain non-binding and lack enforcement mechanisms, relying instead on voluntary cooperation among states with divergent interests and capabilities.

Regional approaches to climate migration governance have shown promise in certain contexts. The African Union’s Kampala Convention, which entered into force in 2012, explicitly addresses displacement caused by natural disasters and climate change, providing a legal framework for protection and assistance within the continent. The Pacific Access Category scheme operated by New Zealand offers permanent residence to a limited number of citizens from specific Pacific island nations facing climate threats, representing an innovative pre-emptive migration strategy. However, these regional solutions remain fragmented and limited in scope, unable to address the global scale of climate migration.

Proactive relocation schemes, sometimes termed planned relocations, offer an alternative to reactive crisis management. Fiji has undertaken several community relocations away from vulnerable coastal areas, attempting to preserve social structures and cultural ties during the transition. Such initiatives require extensive planning, substantial financial resources, and genuine consultation with affected communities to ensure that relocation does not constitute a violation of rights. The ethical complexities surrounding planned relocation are profound: questions arise regarding who decides when relocation becomes necessary, how destination sites are selected, and whether communities should be kept together or integrated into existing settlements.

The financing of climate migration management and adaptation measures represents a critical challenge. Developed nations, whose historical greenhouse gas emissions have contributed disproportionately to climate change, bear a moral responsibility to assist developing countries that are most affected by climate migration. The Green Climate Fund and other financial mechanisms aim to channel resources toward adaptation and resilience-building in vulnerable regions. However, funding commitments frequently fall short of pledges, and bureaucratic complexities impede the disbursement of available resources. Moreover, determining whether funds should prioritize in-situ adaptation to reduce migration pressures or facilitate safe migration pathways involves difficult trade-offs.

Labor migration programs tailored to climate-affected populations could provide legal channels for movement while addressing labor shortages in destination countries. Seasonal agricultural work schemes in Australia and New Zealand that include Pacific islanders demonstrate how migration opportunities can support livelihoods while building resilience in home communities. Expanding such programs and linking them explicitly to climate adaptation strategies could create mutually beneficial arrangements. Critics, however, warn against instrumentalizing migration solely for economic purposes without adequate protection of migrants’ rights and wellbeing.

The role of technology and data in managing climate migration is increasingly recognized. Early warning systems for extreme weather events enable timely evacuations, reducing casualties and displacement duration. Climate modeling and risk mapping help identify communities at heightened vulnerability, allowing for targeted adaptation investments. Biometric identification systems and digital registration can facilitate the delivery of assistance to displaced populations. Yet technological solutions raise concerns about privacy, surveillance, and the potential for exclusionary practices if data systems are used to restrict rather than facilitate movement.

Public perception and political discourse surrounding climate migration significantly influence policy outcomes. In many destination countries, migration is viewed through a security lens, with climate migrants portrayed as threats to economic stability and cultural identity. This securitization of migration can lead to restrictive policies that prioritize border control over humanitarian obligations. Conversely, framing climate migration as an adaptation strategy emphasizes human agency and potential contributions to destination societies. Strategic communication that highlights the shared challenges of climate change and the benefits of well-managed migration is essential for building public support for inclusive policies.

Ultimately, effective governance of climate migration requires a paradigm shift from viewing migration as a problem to be prevented toward recognizing it as a legitimate adaptation strategy deserving of support and protection. This transformation demands enhanced international cooperation, increased financial commitments, legal innovations that bridge existing gaps, and sustained engagement with affected communities to ensure their voices shape policy responses.

Questions 14-26

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

- What does the passage suggest about projections of future climate migration?

- A. They are completely accurate

- B. They contain significant methodological uncertainties

- C. They are generally underestimated

- D. They have been proven false

- According to the passage, what makes defining climate migration difficult?

- A. The lack of available statistics

- B. The blur between voluntary and forced displacement

- C. The involvement of too many countries

- D. The absence of any legal frameworks

- The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration can best be described as:

- A. A binding international treaty with enforcement powers

- B. A regional agreement for African nations

- C. A non-binding framework relying on voluntary cooperation

- D. A temporary emergency response mechanism

- What does the passage say about the African Union’s Kampala Convention?

- A. It ignores climate-related displacement

- B. It provides legal protection for those displaced by natural disasters and climate change

- C. It applies only to cross-border migrants

- D. It has not yet been implemented

- According to the passage, planned relocations in Fiji aim to:

- A. Separate communities permanently

- B. Reduce government expenditure

- C. Preserve social structures and cultural ties

- D. Encourage international migration

Questions 19-23

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

The financing of climate migration presents major difficulties. Developed countries have a 19. __ to help developing nations affected by climate migration due to their historical emissions. Financial mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund exist, but actual funding often doesn’t match 20. __, and bureaucratic issues affect the 21. __ of funds. Policy makers must decide whether to focus on 22. __ to prevent migration or create safe migration pathways. Additionally, 23. __ programs could offer legal migration routes while addressing labor shortages in receiving countries.

Questions 24-26

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 2?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Technology provides complete solutions to all challenges of climate migration management.

-

Public perception of climate migration influences the development of policies.

-

Viewing migration as an adaptation strategy emphasizes the potential contributions migrants can make to destination societies.

PASSAGE 3 – The Intersectionality of Climate Migration: Gender, Inequality, and Human Security

Độ khó: Hard (Band 7.0-9.0)

Thời gian đề xuất: 23-25 phút

The nexus between climate change and human mobility is increasingly understood not as a simple cause-and-effect relationship, but rather as a complex, mediated process shaped by existing social, economic, and political structures. Contemporary scholarly discourse has moved beyond deterministic narratives that portray environmental change as directly producing migration flows, toward more nuanced analytical frameworks that recognize climate change as a threat multiplier operating within broader contexts of vulnerability, inequality, and adaptive capacity. This conceptual evolution is particularly evident in examinations of how intersecting identities and power relations—including gender, class, ethnicity, and age—differentially shape both exposure to climate risks and capacity to respond through migration or other adaptation strategies.

Gender dynamics constitute a critical yet historically under-examined dimension of climate migration. Feminist scholars have demonstrated that climate change impacts are not gender-neutral, as pre-existing patriarchal structures and gendered divisions of labor create differentiated vulnerabilities. In many agrarian societies, women bear primary responsibility for water collection, subsistence farming, and household food security—tasks that become exponentially more difficult as environmental conditions deteriorate. When men migrate in response to climate stresses, women often assume additional burdens as de facto household heads, managing agricultural production and care responsibilities with diminished resources. This phenomenon, sometimes termed the “feminization of agriculture,” has profound implications for both origin and destination communities, yet remains inadequately addressed in mainstream migration governance frameworks.

The decision-making processes surrounding climate migration are themselves deeply gendered. Research indicates that women’s participation in household migration decisions is frequently constrained by normative prescriptions regarding mobility and spatial boundaries. In some cultural contexts, unaccompanied female migration carries social stigma, limiting women’s ability to pursue adaptive migration strategies independently. Conversely, in situations where entire households relocate, women may have minimal agency in determining timing, destination, or conditions of movement. During transit and in destination settings, female migrants face heightened risks of gender-based violence, trafficking, and exploitation—vulnerabilities exacerbated by irregular migration status and lack of legal protection. These gendered dimensions of climate migration intersect with other axes of marginalization, creating compounded disadvantages for women from ethnic minorities, lower castes, or indigenous communities.

Yet framing women solely as victims obscures their agency and resilience. Ethnographic research reveals how women climate migrants actively navigate constraints, forge support networks, engage in collective action, and contribute economically to both sending and receiving communities. Some studies document how migration can provide women with opportunities to transcend restrictive gender norms, access education and employment, and participate in decision-making processes previously unavailable to them. Understanding these heterogeneous experiences requires moving beyond essentialist categorizations toward intersectional analyses that recognize diverse positionalities and capabilities within the category of “women climate migrants.”

The relationship between climate migration and human security operates at multiple scales. At the individual level, climate-induced displacement threatens core security dimensions including livelihoods, health, and personal safety. The disruption of social networks and traditional support systems during migration can undermine psychosocial wellbeing, contributing to mental health challenges that receive insufficient attention in humanitarian responses. At the community level, large-scale climate migration can alter demographic compositions, strain social cohesion, and generate competition over scarce resources such as land, water, and employment opportunities. These local tensions occasionally escalate into violent conflict, though research consistently demonstrates that environmental migration rarely causes conflict directly; rather, it interacts with pre-existing grievances, poor governance, and economic marginalization to elevate conflict risks.

The securitization discourse surrounding climate migration—particularly prominent in policy circles of developed nations—warrants critical examination. Framing climate migration primarily as a security threat to receiving states risks obscuring humanitarian obligations and legitimizing exclusionary border policies. This rhetorical strategy often invokes scenarios of overwhelming migration flows destabilizing societies and economies, despite limited empirical evidence supporting such catastrophic projections. The securitization paradigm implicitly constructs climate migrants as potential threats rather than rights-bearing individuals deserving protection, thereby justifying restrictive measures that may violate fundamental human rights. Alternative framings that emphasize human security—the security of individuals and communities—offer more ethically grounded and potentially more effective approaches to climate migration governance.

Loss and damage represents an emerging conceptual and policy framework with significant implications for climate migration. The concept refers to negative impacts of climate change that cannot be avoided through mitigation or adaptation measures, acknowledging that some communities face irreversible losses including territory, cultural sites, and ways of life. Small Island Developing States have been particularly vocal in demanding that historical emitters accept responsibility for loss and damage, including through financial compensation. The extent to which loss and damage frameworks should address displacement and the relocation of entire communities remains contested. Some advocates argue for recognizing a “right to migrate” for populations facing uninhabitable conditions due to climate change, while others emphasize the right to remain and receive support for in-situ adaptation. These positions reflect deeper philosophical questions about climate justice, historical responsibility, and the obligations of the international community.

The knowledge production surrounding climate migration itself merits reflexive consideration. Much research originates from institutions in the Global North and employs methodological approaches that may not adequately capture the lived experiences, priorities, and knowledge systems of affected communities in the Global South. Participatory research methodologies that center the voices and perspectives of climate migrants themselves can generate insights unavailable through conventional approaches, while simultaneously empowering communities to shape narratives about their experiences. Decolonizing climate migration research requires acknowledging epistemic injustices—the marginalization of certain forms of knowledge—and actively working to redress power imbalances in how research is conducted, interpreted, and disseminated.

Looking forward, addressing the challenges of climate migration necessitates transformative approaches that tackle root causes of vulnerability rather than merely managing symptoms. This includes ambitious climate mitigation to limit temperature increases, substantial investments in adaptation to reduce displacement pressures, and fundamental reforms to global economic structures that perpetuate inequality and environmental degradation. Migration governance frameworks must integrate human rights-based approaches that prioritize dignity, agency, and protection regardless of migration status. Gender-responsive policies that recognize and address differentiated impacts and needs are essential. Ultimately, the climate migration challenge invites reconsideration of foundational concepts including sovereignty, citizenship, and belonging in an era of planetary-scale environmental change.

Quản lý di cư toàn cầu do biến đổi khí hậu với những thách thức về chính sách và quyền con người

Quản lý di cư toàn cầu do biến đổi khí hậu với những thách thức về chính sách và quyền con người

Questions 27-40

Questions 27-31

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

-

Feminist scholars have shown that climate change impacts

-

The “feminization of agriculture” refers to situations where

-

Research on migration decision-making indicates that

-

Ethnographic studies reveal that women climate migrants

-

The securitization discourse surrounding climate migration

A. actively build support networks and engage in collective action

B. are shaped by pre-existing patriarchal structures

C. risks obscuring humanitarian obligations toward migrants

D. women take on additional farming responsibilities when men migrate

E. always leads to violent conflicts in receiving areas

F. women’s mobility choices are often constrained by cultural norms

G. eliminates all gender inequalities in destination communities

H. provides complete solutions to adaptation challenges

Questions 32-36

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

Write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

-

Climate change directly causes migration flows in a simple cause-and-effect manner.

-

Environmental migration alone directly causes violent conflicts in receiving communities.

-

Securitization framing of climate migration can legitimize restrictive border policies.

-

Small Island Developing States have demanded that historical emitters take responsibility for loss and damage.

-

All research on climate migration successfully captures the perspectives of affected communities.

Questions 37-40

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

-

What term describes climate change’s role in making existing problems worse rather than being the sole cause?

-

What type of research methodologies can help center the voices of climate migrants themselves?

-

What framework addresses negative climate impacts that cannot be avoided through mitigation or adaptation?

-

What type of approaches must migration governance frameworks integrate to prioritize dignity and protection?

Answer Keys – Đáp Án

PASSAGE 1: Questions 1-13

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- TRUE

- FALSE

- slow-onset events

- rural-to-urban

- brain drain

- remittances

- C

- B

- C

- D

PASSAGE 2: Questions 14-26

- B

- B

- C

- B

- C

- moral responsibility

- pledges

- disbursement

- in-situ adaptation

- labor migration

- NO

- YES

- YES

PASSAGE 3: Questions 27-40

- B

- D

- F

- A

- C

- NO

- NO

- YES

- YES

- NO

- threat multiplier

- participatory research methodologies

- loss and damage

- human rights-based approaches

Giải Thích Đáp Án Chi Tiết

Passage 1 – Giải Thích

Câu 1: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: officially recognized, same international laws, refugees fleeing war

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: Bài đọc nói rõ “Unlike traditional refugees fleeing war or persecution, climate refugees face a unique set of challenges that are not yet fully recognized under international law.” Điều này mâu thuẫn với phát biểu câu hỏi, do đó đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 2: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: 2019, more people displaced, weather-related disasters, armed conflicts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: Bài viết nêu “weather-related disasters displaced approximately 23.9 million people in 2019 alone. This figure represents nearly three times the number of people displaced by conflict and violence during the same period.” Thông tin này khớp với phát biểu trong câu hỏi.

Câu 3: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Maldives, completely submerged, rising sea levels

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 7-8

- Giải thích: Bài đọc chỉ nói “Small island nations like Tuvalu and the Maldives face the threat of complete submersion” (đối mặt với nguy cơ), không nói đã bị chìm hoàn toàn. Do đó đáp án là FALSE.

Câu 4: TRUE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Bangladesh, 20 hectares, coastal land, every day

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: Thông tin “in Bangladesh, coastal erosion destroys approximately 20 hectares of land daily” khớp chính xác với phát biểu câu hỏi.

Câu 5: FALSE

- Dạng câu hỏi: True/False/Not Given

- Từ khóa: cross international borders, same protections, conventional refugees

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 4-7

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “This legal gap leaves climate refugees in a precarious position, often unable to access the protections and assistance available to conventional refugees.” Điều này mâu thuẫn với câu hỏi.

Câu 6: slow-onset events

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: desertification, glacial retreat, gradually force

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: Cụm “Slow-onset events such as desertification, sea-level rise, and glacial retreat” chính xác mô tả các sự kiện diễn ra từ từ.

Câu 7: rural-to-urban

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: most typical movement pattern

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 1

- Giải thích: “Rural-to-urban migration represents the most common pattern of climate-related movement” – paraphrase của “most typical movement pattern.”

Câu 8: brain drain

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: productive younger people leave, home regions suffer

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Sending regions experience brain drain as younger, more educated individuals are typically the first to leave” mô tả chính xác hiện tượng này.

Câu 9: remittances

- Dạng câu hỏi: Sentence Completion

- Từ khóa: money sent back home, help families cope

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 3-4

- Giải thích: “Remittances sent by migrants back to their home regions provide crucial financial support” – câu này định nghĩa rõ thuật ngữ.

Câu 10: C (23.9 million)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: approximate number, displaced, 2019

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 3

- Giải thích: Con số “approximately 23.9 million people in 2019” được nêu rõ ràng trong bài.

Câu 11: B (Growth of informal settlements)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: consequence, rural-to-urban climate migration

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “This internal migration places enormous pressure on urban infrastructure, leading to the expansion of informal settlements” là hậu quả được nêu cụ thể.

Câu 12: C (It does not recognize environmental factors for refugee status)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: 1951 Refugee Convention

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 4-6

- Giải thích: “The 1951 Refugee Convention…does not recognize environmental factors as grounds for refugee status” khớp với đáp án C.

Câu 13: D (Women and children)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: most vulnerable group

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn bắt đầu bằng “Women and children constitute the most vulnerable groups among climate migrants.”

Các dạng câu hỏi IELTS Reading về biến đổi khí hậu và di cư với chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả

Các dạng câu hỏi IELTS Reading về biến đổi khí hậu và di cư với chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả

Passage 2 – Giải Thích

Câu 14: B (They contain significant methodological uncertainties)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: projections, future climate migration

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 3-5

- Giải thích: “Estimates suggest that by 2050…though the methodological uncertainties inherent in such projections are considerable” khớp với đáp án B.

Câu 15: B (The blur between voluntary and forced displacement)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: defining climate migration difficult

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “The dichotomy between voluntary migration and forced displacement becomes blurred” giải thích khó khăn trong việc định nghĩa.

Câu 16: C (A non-binding framework relying on voluntary cooperation)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Global Compact

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “These frameworks, however, remain non-binding and lack enforcement mechanisms, relying instead on voluntary cooperation” mô tả chính xác.

Câu 17: B (It provides legal protection for those displaced by natural disasters and climate change)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: Kampala Convention

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “explicitly addresses displacement caused by natural disasters and climate change, providing a legal framework for protection” khớp với đáp án B.

Câu 18: C (Preserve social structures and cultural ties)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Multiple Choice

- Từ khóa: planned relocations, Fiji

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “attempting to preserve social structures and cultural ties during the transition” là mục tiêu được nêu rõ.

Câu 19: moral responsibility

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: developed countries, help developing nations

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Developed nations…bear a moral responsibility to assist developing countries” cung cấp cụm từ chính xác.

Câu 20: pledges

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: funding doesn’t match

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 5-6

- Giải thích: “funding commitments frequently fall short of pledges” – pledges là từ cần điền.

Câu 21: disbursement

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: bureaucratic issues affect

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 6

- Giải thích: “bureaucratic complexities impede the disbursement of available resources” cung cấp từ cần thiết.

Câu 22: in-situ adaptation

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: focus on, to prevent migration

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 7-8

- Giải thích: “whether funds should prioritize in-situ adaptation to reduce migration pressures” chứa cụm từ chính xác.

Câu 23: labor migration

- Dạng câu hỏi: Summary Completion

- Từ khóa: programs, legal migration routes, labor shortages

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1

- Giải thích: “Labor migration programs tailored to climate-affected populations” mở đầu đoạn văn này.

Câu 24: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: technology, complete solutions, all challenges

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8

- Giải thích: Đoạn văn nêu lợi ích của công nghệ nhưng cũng nêu “Yet technological solutions raise concerns” – không phải giải pháp hoàn hảo.

Câu 25: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: public perception, influences policies

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Public perception and political discourse surrounding climate migration significantly influence policy outcomes” khẳng định rõ ràng.

Câu 26: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: viewing migration as adaptation strategy, contributions to destination societies

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “framing climate migration as an adaptation strategy emphasizes human agency and potential contributions to destination societies” khớp chính xác.

Passage 3 – Giải Thích

Câu 27: B (are shaped by pre-existing patriarchal structures)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: Feminist scholars, climate change impacts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Feminist scholars have demonstrated that climate change impacts are not gender-neutral, as pre-existing patriarchal structures…create differentiated vulnerabilities.”

Câu 28: D (women take on additional farming responsibilities when men migrate)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: feminization of agriculture

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 2, dòng 5-7

- Giải thích: “When men migrate…women often assume additional burdens as de facto household heads, managing agricultural production…This phenomenon, sometimes termed the ‘feminization of agriculture.'”

Câu 29: F (women’s mobility choices are often constrained by cultural norms)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: research, migration decision-making

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 3, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Research indicates that women’s participation in household migration decisions is frequently constrained by normative prescriptions regarding mobility.”

Câu 30: A (actively build support networks and engage in collective action)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: ethnographic studies, women climate migrants

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 4, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Ethnographic research reveals how women climate migrants actively navigate constraints, forge support networks, engage in collective action.”

Câu 31: C (risks obscuring humanitarian obligations toward migrants)

- Dạng câu hỏi: Matching Sentence Endings

- Từ khóa: securitization discourse

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-3

- Giải thích: “Framing climate migration primarily as a security threat to receiving states risks obscuring humanitarian obligations.”

Câu 32: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: directly causes, simple cause-and-effect

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 1-4

- Giải thích: Bài viết nói rõ “not as a simple cause-and-effect relationship, but rather as a complex, mediated process” – mâu thuẫn với câu hỏi.

Câu 33: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: environmental migration alone, directly causes, violent conflicts

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 5, dòng 6-8

- Giải thích: “research consistently demonstrates that environmental migration rarely causes conflict directly; rather, it interacts with pre-existing grievances” – không phải nguyên nhân trực tiếp.

Câu 34: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: securitization, legitimizing, restrictive border policies

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 6, dòng 2-4

- Giải thích: “Framing climate migration primarily as a security threat…risks obscuring humanitarian obligations and legitimizing exclusionary border policies” khẳng định điều này.

Câu 35: YES

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: Small Island Developing States, historical emitters, responsibility

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “Small Island Developing States have been particularly vocal in demanding that historical emitters accept responsibility for loss and damage” xác nhận rõ ràng.

Câu 36: NO

- Dạng câu hỏi: Yes/No/Not Given

- Từ khóa: all research, successfully captures, perspectives of affected communities

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 1-3

- Giải thích: “Much research…may not adequately capture the lived experiences, priorities, and knowledge systems of affected communities” – mâu thuẫn với “all research successfully.”

Câu 37: threat multiplier

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Từ khóa: makes existing problems worse, not sole cause

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 1, dòng 5

- Giải thích: “climate change as a threat multiplier operating within broader contexts” mô tả vai trò này chính xác.

Câu 38: participatory research methodologies

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Từ khóa: center voices, climate migrants themselves

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 8, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “Participatory research methodologies that center the voices and perspectives of climate migrants themselves” là thuật ngữ chính xác.

Câu 39: loss and damage

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Từ khóa: framework, negative impacts, cannot be avoided

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 7, dòng 1-2

- Giải thích: “Loss and damage represents an emerging conceptual and policy framework…The concept refers to negative impacts of climate change that cannot be avoided.”

Câu 40: human rights-based approaches

- Dạng câu hỏi: Short-answer Question

- Từ khóa: migration governance frameworks, integrate, prioritize dignity, protection

- Vị trí trong bài: Đoạn 9, dòng 4-5

- Giải thích: “Migration governance frameworks must integrate human rights-based approaches that prioritize dignity, agency, and protection” cung cấp cụm từ đầy đủ.

Từ Vựng Quan Trọng Theo Passage

Passage 1 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| relocate | v | /ˌriːləʊˈkeɪt/ | di dời, tái định cư | individuals who must relocate due to sudden changes | relocate permanently, forcibly relocate |

| unprecedented | adj | /ʌnˈpresɪdentɪd/ | chưa từng có | its scale is unprecedented | unprecedented scale, unprecedented level |

| submersion | n | /səbˈmɜːʃn/ | sự chìm xuống nước | threat of complete submersion | complete submersion, gradual submersion |

| prolonged | adj | /prəˈlɒŋd/ | kéo dài | prolonged droughts that devastate agriculture | prolonged drought, prolonged period |

| multifaceted | adj | /ˌmʌltiˈfæsɪtɪd/ | nhiều khía cạnh | drivers are complex and multifaceted | multifaceted problem, multifaceted approach |

| coastal erosion | n | /ˈkəʊstl ɪˈrəʊʒn/ | xói mòn bờ biển | coastal erosion destroys land | severe coastal erosion, prevent coastal erosion |

| informal settlements | n | /ɪnˈfɔːml ˈsetlmənts/ | khu ổ chuột | expansion of informal settlements | growth of informal settlements, live in informal settlements |

| precarious | adj | /prɪˈkeəriəs/ | bấp bênh, không chắc chắn | leaves refugees in a precarious position | precarious position, precarious situation |

| brain drain | n | /breɪn dreɪn/ | chảy máu chất xám | experience brain drain as younger individuals leave | suffer brain drain, prevent brain drain |

| vicious cycle | n | /ˈvɪʃəs ˈsaɪkl/ | vòng luẩn quẩn | creating a vicious cycle of degradation | trapped in vicious cycle, break vicious cycle |

| exploitation | n | /ˌeksplɔɪˈteɪʃn/ | sự bóc lột | face exploitation during transit | sexual exploitation, prevent exploitation |

| resilience | n | /rɪˈzɪliəns/ | khả năng phục hồi | demonstrate remarkable resilience | build resilience, community resilience |

Passage 2 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| formidable | adj | /fəˈmɪdəbl/ | ghê gớm, khổng lồ | one of the most formidable challenges | formidable challenge, formidable task |

| unprecedented | adj | /ʌnˈpresɪdentɪd/ | chưa từng có | scale is unprecedented | unprecedented scale, unprecedented crisis |

| dichotomy | n | /daɪˈkɒtəmi/ | sự đối lập | dichotomy between voluntary and forced | false dichotomy, sharp dichotomy |

| ambiguity | n | /ˌæmbɪˈɡjuːəti/ | sự mơ hồ | conceptual ambiguity complicates efforts | moral ambiguity, legal ambiguity |

| multilateral | adj | /ˌmʌltiˈlætərəl/ | đa phương | multilateral initiatives have emerged | multilateral agreement, multilateral cooperation |

| non-binding | adj | /nɒn ˈbaɪndɪŋ/ | không ràng buộc | frameworks remain non-binding | non-binding agreement, non-binding resolution |

| fragmented | adj | /ˈfræɡmentɪd/ | phân mảnh | regional solutions remain fragmented | fragmented approach, fragmented system |

| proactive | adj | /prəʊˈæktɪv/ | chủ động | proactive relocation schemes | proactive approach, proactive measures |

| disbursement | n | /dɪsˈbɜːsmənt/ | sự giải ngân | impede disbursement of resources | fund disbursement, delay disbursement |

| in-situ adaptation | n | /ɪn ˈsɪtʃuː ˌædæpˈteɪʃn/ | thích nghi tại chỗ | prioritize in-situ adaptation | promote in-situ adaptation, in-situ adaptation strategies |

| mutually beneficial | adj | /ˈmjuːtʃuəli ˌbenɪˈfɪʃl/ | cùng có lợi | create mutually beneficial arrangements | mutually beneficial agreement, mutually beneficial relationship |

| securitization | n | /sɪˌkjʊərətaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | an ninh hóa | securitization of migration | securitization discourse, securitization process |

| exclusionary | adj | /ɪkˈskluːʒənri/ | loại trừ | exclusionary practices if data systems used | exclusionary policies, exclusionary approach |

| paradigm shift | n | /ˈpærədaɪm ʃɪft/ | chuyển đổi mô hình | requires a paradigm shift | undergo paradigm shift, fundamental paradigm shift |

Từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề biến đổi khí hậu và di cư với phiên âm và ví dụ minh họa

Từ vựng IELTS Reading chủ đề biến đổi khí hậu và di cư với phiên âm và ví dụ minh họa

Passage 3 – Essential Vocabulary

| Từ vựng | Loại từ | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Ví dụ từ bài | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nexus | n | /ˈneksəs/ | mối liên hệ | nexus between climate change and mobility | climate-migration nexus, water-energy nexus |

| mediated | adj | /ˈmiːdieɪtɪd/ | trung gian | complex, mediated process | mediated relationship, mediated effect |

| deterministic | adj | /dɪˌtɜːmɪˈnɪstɪk/ | định đoạt | beyond deterministic narratives | deterministic view, deterministic model |

| nuanced | adj | /ˈnjuːɑːnst/ | tinh tế, nhiều sắc thái | more nuanced analytical frameworks | nuanced understanding, nuanced approach |

| threat multiplier | n | /θret ˈmʌltɪplaɪə/ | yếu tố nhân đôi mối đe dọa | climate change as a threat multiplier | act as threat multiplier, threat multiplier effect |

| intersecting | adj | /ˌɪntəˈsektɪŋ/ | giao nhau | intersecting identities and power relations | intersecting factors, intersecting challenges |

| patriarchal | adj | /ˌpeɪtriˈɑːkl/ | gia trưởng | pre-existing patriarchal structures | patriarchal society, patriarchal system |

| differentiated | adj | /ˌdɪfəˈrenʃieɪtɪd/ | khác biệt | create differentiated vulnerabilities | differentiated approach, differentiated impacts |

| de facto | adj | /deɪ ˈfæktəʊ/ | trên thực tế | women as de facto household heads | de facto leader, de facto control |

| feminization | n | /ˌfemɪnaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | nữ hóa | feminization of agriculture | feminization of poverty, feminization of labor |

| normative | adj | /ˈnɔːmətɪv/ | chuẩn mực | constrained by normative prescriptions | normative framework, normative standards |

| stigma | n | /ˈstɪɡmə/ | kỳ thị | female migration carries social stigma | social stigma, reduce stigma |

| trafficking | n | /ˈtræfɪkɪŋ/ | nạn buôn người | risks of trafficking and exploitation | human trafficking, combat trafficking |

| heterogeneous | adj | /ˌhetərəˈdʒiːniəs/ | đa dạng, không đồng nhất | heterogeneous experiences | heterogeneous population, heterogeneous group |

| essentialist | adj | /ɪˈsenʃəlɪst/ | bản chất luận | beyond essentialist categorizations | essentialist view, essentialist assumptions |

| psychosocial | adj | /ˌsaɪkəʊˈsəʊʃl/ | tâm lý xã hội | undermine psychosocial wellbeing | psychosocial support, psychosocial impacts |

| securitization | n | /sɪˌkjʊərətaɪˈzeɪʃn/ | an ninh hóa | securitization discourse warrants examination | securitization of migration, securitization paradigm |

| irreversible | adj | /ˌɪrɪˈvɜːsəbl/ | không thể đảo ngược | face irreversible losses | irreversible damage, irreversible change |

| epistemic | adj | /ˌepɪˈstemɪk/ | tri thức | epistemic injustices | epistemic violence, epistemic framework |

| transformative | adj | /trænsˈfɔːmətɪv/ | mang tính chuyển đổi | transformative approaches | transformative change, transformative potential |

Kết bài

Chủ đề quản lý di cư toàn cầu do biến đổi khí hậu không chỉ là một vấn đề môi trường mà còn là thách thức nhân đạo, chính trị và kinh tế phức tạp đang định hình thế kỷ 21. Với hàng triệu người phải di dời do các tác động của khí hậu, việc hiểu rõ các khía cạnh của vấn đề này là cực kỳ quan trọng, không chỉ cho kỳ thi IELTS mà còn cho nhận thức toàn cầu của chúng ta.

Đề thi IELTS Reading hoàn chỉnh này đã cung cấp cho bạn ba passages với độ khó tăng dần từ band 5.0 đến 9.0, bao gồm đầy đủ 40 câu hỏi với 7 dạng khác nhau giống như trong kỳ thi thực tế. Passage 1 giới thiệu khái niệm cơ bản về climate refugees và các thách thức ban đầu, Passage 2 đi sâu vào các chính sách ứng phó và khung pháp lý quốc tế, trong khi Passage 3 phân tích các khía cạnh phức tạp về giới tính, bất bình đẳng và an ninh con người trong bối cảnh di cư khí hậu.

Phần đáp án chi tiết không chỉ cung cấp kết quả đúng sai mà còn giải thích rõ ràng vị trí thông tin trong bài, kỹ thuật paraphrase và cách tiếp cận từng dạng câu hỏi. Điều này giúp bạn không chỉ kiểm tra kết quả mà còn hiểu sâu về phương pháp làm bài hiệu quả. Bảng từ vựng được phân loại theo từng passage với phiên âm, nghĩa tiếng Việt, ví dụ trong ngữ cảnh và collocations sẽ giúp bạn mở rộng vốn từ học thuật đáng kể.

Hãy luyện tập đề thi này trong điều kiện thi thật (60 phút không gián đoạn), sau đó dành thời gian xem lại đáp án và học từ vựng kỹ lưỡng. Việc lặp lại quá trình này với nhiều đề thi khác nhau sẽ giúp bạn tự tin hơn và đạt band điểm cao trong phần IELTS Reading. Chúc bạn ôn tập hiệu quả và thành công trong kỳ thi IELTS sắp tới!